|

I'm excited to say that Writing in Margins made it onto Feedspot's Top 45 Fairy Tale Blogs!

A while back, I discovered that an author named Ethel Reader had written a gender-swapped retelling of "The Little Mermaid" all the way back in 1909. Well, actually there are a lot of other elements mixed in. The story The novella begins by introducing the undersea kingdom of the Mer-People. In the kingdom is the Garden of the Red Flowers; a flower blooms and an ethereal, triumphant music plays whenever a Mer-Person gains a soul. The Little Merman, the main character, is drawn to the land from a young age. One day he meets a human Princess on the beach, and they quickly become friends. The Princess eventually explains that her kingdom is plagued by two dragons. She is an orphan, and the kingdom is ruled by her uncle, the Regent, until the day when a Prince will come to slay the dragons and marry her. The Little Merman wants increasingly to have legs and a soul like a human; there’s a sequence where he goes into town on crutches and ends up buying some soles (the shoe version). However, after some years, the Princess tries to take action about the dragons and protect her people. The Regent, who is actually a wicked and power-hungry magician, sends her away to school. The Little Merman asks her to marry him, but she explains that "I can't marry you without a soul, because I might lose mine" (p. 52). The Little Merman plays her a farewell song on the harp. The Little Merman talks to the Mer-Father, an old merman who explains that he once gained legs and went on land to marry a shepherdess whom he loved. However, when he made the mistake of revealing who he really was, the humans were terrified and drove him out. Unable to find a soul, he returned to the sea. The Mer-Father tells the Little Merman how to get to an underground cave, where he will meet a blacksmith who can give him legs. He gives him a coral token; as long as he keeps it with him, he can return to the sea and become a merman again. The Little Merman goes to the blacksmith, who happens to be a dwarf living under a mountain. He pays with gems from under the sea, and the blacksmith cuts off the Merman’s tail to replace it with human legs. The Little Merman wakes up on the beach, human and equipped with armor and weapons. The Mer-Father has also sent him a magical horse from the sea. He proceeds to the castle, where people assume he is one of the princes there to fight the dragon and compete for the Princess’s hand. The Princess, now eighteen years old, has just returned from college. The Princess doesn’t acknowledge the Little Merman—who is going by the name “the Sea-Prince”—and he’s afraid to identify himself after the Mer-Father’s story of being cast out. Every June 21st the Dragon of the Rocks appears and people try to appease it with offerings of treasure; every December 21st the same thing happens with the Dragon of the Lake. The princes go out to fight the Dragon of the Rocks, but it vanishes through a solid wall of the mountain; they all give up in disgust except for the Little Merman, who has been spending time with the Princess and now shares her righteous fury on her people’s behalf. With help from the dwarf blacksmith, he finds a way into the dragon's lair and slays it. The people adore him, while the resentful Regent spreads rumors against him, and the Little Merman is secretly disappointed that he hasn’t earned a soul. In December, the Little Merman goes out to fight the Dragon of the Lake. It drags him underwater, but he can still breathe underwater, and slays it too. The wedding is announced, but the Little Merman is conflicted; he still doesn’t have a soul, and if the Princess marries him, she will lose hers. He also fends off an assassination attempt from the Regent, but saves the Regent's life. The next morning, the Little Merman announces to the people that he is from the sea and has no soul. The Princess always knew it was him and loves him anyway, but everyone else rejects him and the Regent orders him thrown in prison. After a trial, he will be burned to death. The Princess gets the trial delayed and begins studying the royal library's law books. The Merman waits in jail, only to hear the Mer-People calling to him. They offer to break him out of jail with a tidal wave, but he refuses, worried about the humans. The Dwarf Blacksmith also offers him an escape, reminding him that he won’t get a soul either way; the Merman refuses again. Then the Little Merman's loyal human Squire visits. He has raised an army from the countryfolk, with the Sea-People and the Dwarfs also offering to fight. It may be bloody, but if they win, the Little Merman will have a chance to earn a soul. The Little Merman vehemently refuses; he will not kill his enemy, and he knows the kind of collateral damage that the Sea-People and the Dwarfs will bring to the kingdom. He gives the Squire his coral token, telling him to take it back to the Mer-Father; he is not returning to the sea. Alone in his cell, waiting for death, he hears the music that means a merperson has won a soul. The next day is the trial, where the Regent accuses the Little Merman of deception and treason. The Princess speaks up in his defense. The only issue is that the Little Merman doesn’t have a soul, so she reveals that she has found a record of a man from the Sea-People who came on land, was similarly accused of having no soul, and asked how he could get one. A local Wise Man told him that he would only win a soul when the Wise Man’s dry staff blossomed; at that moment, the staff put out flowers. The judge and lawyers decide to try this out, the Regent gleefully offers his staff, and the staff blossoms. The shocked Regent confesses all his crimes, including that he was the one who brought the dragons. The Little Merman intervenes to spare him from execution. The Little Merman and the Princess get married and rule the kingdom well, and there is a new red flower in the underwater garden. Background and Inspiration The Story of the Little Merman was initially released in 1907; it was a novella, with the same volume including an additional novella, The Story of the Queen of the Gnomes and the True Prince. Both were illustrated by Frank Cheyne Papé. The Story of the Little Merman was reprinted on its own in 1979. I have been unable to find much information about Ethel Reader, or any books by her other than this. In the dedication, she describes herself as the maiden aunt to a girl named Frances. The story itself has many literary allusions. It’s maybe twee at times but also had a lot of really funny lines. The overall mood made me think of George MacDonald’s writing. Some quotes that stuck with me:

First and most prominently, “The Story of the Little Merman” is an allusion to “The Little Mermaid.” Not only is the title similar, there is the description of the Garden of the Red Flowers, paralleling the Little Mermaid’s garden. There is also the overall plotline of the merman longing for both his human love and an immortal soul, going through a painful ordeal to become human, and winning a soul through self-sacrifice - with a final moral test where his loved ones beg him to save himself by sacrificing everything he's been fighting for. (One distinction: The Little Mermaid just gets the chance at an immortal soul, while the Little Merman actually gets his soul, along with a happily-ever-after with the Princess.) That's about where the similarities end. Reader’s book adds elements of dragon-slayer stories, and - most prominently - it plays on Matthew Arnold’s merman poems. “The Forsaken Merman” (1849) is one I recognized. Related to the Danish ballad of Agnete and the Merman, it tells of a merman who has taken a human wife and has children with her. The human woman hears the church bells and wishes to go back to land for Easter Mass: “I lose my poor soul, Merman! here with thee.” Once there, she never returns, leaving her husband and children forlorn. “The Neckan” (1853/1869) was new to me. This poem also deals with a human/sea-creature romance and the question of souls and religion. The Neckan takes a human wife, but she weeps that she does not have a Christian husband. So he goes on land, but when he introduces himself, humans fear and revile him. This is directly based on a Danish folktale, collected in Benjamin Thorpe's Northern Mythology: A priest riding one evening over a bridge, heard the most delightful tones of a stringed instrument, and, on looking round, saw a young man, naked to the waist, sitting on the surface of the water, with a red cap and yellow locks… He saw that it was the Neck, and in his zeal addressed him thus : “Why dost thou so joyously strike thy harp ? Sooner shall this dried cane that I hold in my hand grow green and flower, than thou shalt obtain salvation.” Thereupon the unhappy musician cast down his harp, and sat bitterly weeping on the water. The priest then turned his horse, and con tinued his course. But lo ! before he had ridden far, he observed that green shoots and leaves, mingled with most beautiful flowers, had sprung from his old staff. This seemed to him a sign from heaven… He therefore hastened back to the mournful Neck, showed him the green, flowery staff, and said : " Behold ! now my old staff is grown green and flowery like a young branch in a rose garden ; so likewise may hope bloom in the hearts of all created beings ; for their Redeemer liveth ! " Comforted by these words, the Neck again took his harp, the joyous tones of which resounded along the shore the whole livelong night (1851, p. 80) Arnold edited his poem after its first publication. In his first version, the priest rejects the Neckan and that’s it. In his second version, Arnold reintroduces the theme of the miraculous flowering staff. However, instead of being overjoyed like the Neck in the folktale, Arnold's Neckan continues to weep at the cruelty of human souls. The flowering staff is an old and widespread trope; it appears in the biblical story of Aaron, in a legend about St. Joseph, and most similarly in the medieval legend of Tannhauser, where a knight asks a priest if his soul can still be saved after he dallied in an underground fairy realm. While The Story of the Little Merman is clearly influenced by Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” it is equally or more inspired by “The Neckan,” even directly quoting it in one scene. I have never been a fan of the motif that merfolk don’t have souls, but it was an accepted idea in medieval legend. I recently read Poul Anderson’s The Merman’s Children, inspired by the story of Agnete and the Merman and thus distantly related to The Story of the Little Merman. In Anderson’s book, receiving souls is a Borg-like assimilation that costs the merfolk their old identities and memories. It’s a bitter take on the conflict between Christianity and paganism. Reader has a much more positive view on merfolk gaining souls. The merfolk are beautiful, but they just kind of exist, doing no harm and no good. They and other supernatural beings are part of nature. The Little Merman comes truly alive through his time on land, learning passion and emotions, and how to care about people other than himself. He learns how to feel anger and hatred, but these can be positive, the story explains—anger on behalf of vulnerable people, hatred of evil and greed. I like how the story raises the question of how the Merman actually acquired his soul. Did he earn a soul in the moment that he selflessly faced death and sent away his last chance of escape, or was his soul developing all along from the moment when he first saw land? The story hints pretty strongly that it’s the second one. I also really like the play on the Little Mermaid's final choice in Andersen's original. Here, this scene is greatly extended and really delves into the alternatives, raising different possibilities - might the Little Merman return to his old existence, or might he take a moral step back but then continue with his quest for a soul afterwards? He's not willing to do either. Whereas the Little Mermaid has to decide whether to harm her beloved who has hurt her deeply, the Little Merman is urged to kill a mortal enemy who has tried to murder him multiple times. He rejects this partly out of a sense of honor - he has killed dragons but he will not sink to the Regent's level by murdering a human - and partly because he foresees the bloodshed that this kind of war would bring to the whole kingdom. (In the illustrations, the Little Merman wears a crown - possibly of kelp - that looks a little like a crown of thorns.) It's also interesting to contrast the romance with that in The Little Mermaid. Here, the Merman and the Princess are childhood friends. They reconnect as young adults and their relationship deepens. The Merman is inspired by the Princess’s fierce love for her people. He does not have the Little Mermaid’s quest of marrying in order to get a soul; instead he is trying to get a soul so that he can marry the Princess. It’s his concern for her well-being that causes him to reveal his identity and give the chance for her to back out of their mandated engagement, even though it nearly costs him his life. The Little Merman has some fun fish-out-of-water moments and reads as a very peaceful, innocent character. There is a touch of realism in the fact that he gets beat up pretty badly in both dragon-battles and needs a lot of time to recover on both occasions. Meanwhile, the Princess is brave, loyal, and intelligent. She may not ride out to fight the dragons herself, but she’s the one who saves the Merman in the end, using her political savvy and education to delay his trial and build a legal defense. This book is chock-full of folkloric and literary references, and I think I might even prefer its take on souls to that of The Little Mermaid. Bibliography

0 Comments

A while ago, I spent several blog posts reviewing historical figures who have been put forward as the "real Snow White" - both of which turned out to be marketing campaigns with only the flimsiest of connections. Anastasia provides a look at something like the opposite. The real story of Anastasia Romanova is short, brutal and heartbreaking, but it’s been used as the basis for a fairy tale.

On July 17, 1918, the Russian imperial family was executed by Bolshevik revolutionaries. This included the Tsar Nicholas II, his wife the Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, and their children Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei, along with members of their entourage. Their executioners mutilated the bodies and buried them in the woods. Afterwards, the Bolsheviks announced Nicholas's death, but they covered up the deaths of his family and spread misinformation about them. This added fuel to the persistent idea that some might have survived. Numerous impostors appeared claiming to be surviving members of the imperial family who had escaped. The most famous, by far, was Anna Anderson. The Anna Anderson Timeline 1920: An unknown young woman is admitted to a mental hospital after a suicide attempt. Eventually, she begins claiming to be one of the Romanov princesses—initially Tatiana but then Anastasia. By 1922, she has come to the attention of Romanov supporters, friends and surviving relatives, and is using the name Anna (short for Anastasia). Some of the relatives denounce her as a fraud, but others embrace her. Despite her troubled and erratic behavior, and the fact that an investigation in 1927 points to her actually being a missing Polish factory worker named Franziska Schanzkowska, Anna becomes extremely famous. Supporters provide enough money for her to live comfortably. Adopting the surname Anderson, she's introduced to high society in America. Anderson’s story inspires numerous media adaptations, whether movies or stage or books. Some of these adaptations accept her claims; others draw more nuanced portraits that don’t settle on whether or not they believe her. 1928: The silent film Clothes Make the Woman, loosely inspired by Anna Anderson, depicts Princess Anastasia escaping the Bolsheviks with the help of a sympathetic revolutionary and coming to America. 1953: Marcelle Maurette writes a play called Anastasia, in which a team of conmen decide to use an amnesiac woman, "Anna," to fake the return of Princess Anastasia and swindle her grandmother, the Grand Duchess. But Anna might actually be Anastasia. The question never gets a definitive yes-or-no answer. In an ending twist, she falls in love and runs away to lead a normal life. 1956: Ingrid Bergman stars in Anastasia, a film adaptation of Maurette's play. The same year also sees a German film, The Story of Anastasia. 1979: An amateur sleuth discovers the mass grave of the Romanovs, although further investigation is impossible due to the Soviets. 1984: Anna Anderson dies of pneumonia in the U.S. 1991: Collapse of the Soviet Union. DNA analysis confirms that the bodies in the mass grave are those of the Romanovs. However, Alexei and one of the girls (either Maria or Anastasia) are unaccounted for. Tests of Anna Anderson's DNA prove that she was not a Romanov and strongly indicate that she was Franziska Schanzkowska. So after all the debate, all the bitter argument and broken relationships among supporters and opponents, “Anna” is finally proven a fraud . . . but the two missing bodies still leave room for the idea of a surviving Romanov. 1997: Don Bluth's animated film Anastasia loosely adapts the 1956 Ingrid Bergman movie (which, remember, was an adaptation of the 1953 play). This version is straightforwardly marketed as a fairy tale, departing from historical facts in favor of something more Disneyfied. Anastasia is eight instead of seventeen when her family dies, and instead of a Bolshevik revolution, we get Rasputin as an undead wizard who sparks the fall of the Romanovs through black magic and has a talking bat for a sidekick. The lost princess, suffering from amnesia, grows up in an orphanage as "Anya" until she is scooped up by two shysters who see her as an ideal candidate for their scam. One of them—Dimitri—falls for her while gradually realizing that she really is the true Anastasia. Anya reclaims her identity, reunites with her grandmother, and defeats Rasputin, but decides to elope with Dimitri. Other animated Anastasia films mimicked this fairy tale style (two knockoffs, by Golden Films and UAV Entertainment, also came out in 1997). 2007: The last two Romanov bodies are located, and further DNA testing confirms their identities. Some people still try to challenge this or cling to the idea that some of the Romanovs escaped, but at this point it's clear that the entire family died that night in 1918. Exploring the implications Why was it Anastasia, and not any of her siblings, who inspired such fervor? It wasn’t even clear whether the missing body was Anastasia’s or Maria’s. And there were definitely impostors posing as other surviving Romanovs. The name "Anastasia" means "resurrection," which is a romantic coincidence... but the real reason may be much more mundane. It was Anna Anderson. She was more famous than any of the other impostors. And notably, she was originally supposed to be Tatiana. That idea quickly fell apart, partly because she was the wrong height. But whose height matched? Anastasia's. And so Franziska Schanzkowska found her new identity, and Anastasia is now the central figure of a myth because her height matched up with a scammer's. Somehow this makes it feel even more deeply sad. With Don Bluth’s film, a new fairy tale really took shape. And it wasn't the story of Anastasia. It was the story of Anna Anderson—the myth that she and her supporters created around herself, of a lost princess regaining her memories. Maurette's play, and its many derivatives (the 1956 film, Don Bluth's film) tell the narrative of crooks coaching a woman to play the part of Anastasia. This is exactly what detractors accused Anderson and her supporters of. The real story of Anastasia Romanova is a life cut short by brutal violence. Anna Anderson’s fairy tale, by contrast, is romantic and enjoyable. It relies on a very old and widespread trope: the random orphan who discovers that they’re the long-lost heir to the kingdom. Herodotus told a story like this about Cyrus the Great being raised by a shepherd. It's in the story of King Arthur. It's in the Italian fairy tale “The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.” It’s in Madame D'Aulnoy’s fairy tale “The Bee and the Orange Tree” and in the original, highly convoluted "Beauty and the Beast" by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve. It’s Shasta in The Horse and His Boy and Cinder in The Lunar Chronicles. It’s Disney’s Briar Rose and Hercules and Rapunzel (and, oddly enough, also the Barbie version of Rapunzel from 2002). (One unusual touch of the Anastasia myth is that the princess is a little older when she vanishes - not an infant - and amnesia is a lot more likely to be in play.) What's especially interesting is the way the story may have evolved since the graves and DNA tests. In the Maurette-verse of Anastasia stories, Anastasia may discover her true identity, but she ultimately chooses to leave behind the prestige of princesshood and its obsession with the past for a normal life with the man she loves. These stories are typically colored by the real-world context that there is no kingdom for her to go back to, that things have changed too much. What inspired this post was noticing the number of Anastasia retellings out there. I read two of them around the same time a couple of years ago--Heart of Iron by Ashley Poston (2018) and Last of Her Name by Jessica Khoury (2019), both of which are sci-fi retellings of the Anastasia myth set in space. Poston’s book draws a lot from the Don Bluth cartoon. The heroine goes by Ana and her love interest is named Dimitri. The villain has a name similar to Rasputin. There's a pivotal moment where Ana must prove her identity to her grandmother. However, the Maurette-inspired "fraud" plot is played way down, barely a factor at all. Khoury's book takes more of its creative spark from history. As Khoury said in an interview, "what if instead of ending the Anastasia story ... a DNA test was the beginning of her tale?" So it begins with the heroine, Stacia, being spotted as the lost princess via a genetic scan, and having to go on the run. Both of these new stories move away from Maurette's plotline of is-it-or-isn't-it fraud. Instead they focus on the Anastasia figure fighting to take back her kingdom and queenship. It’s much more the fairy tale brand. A 2020 film, Anastasia: Once Upon a Time, is sort of the same animal. It includes supernatural elements and evokes a fairy tale setting with its title. It heavily features Rasputin as an antagonist but features a different setup, following Anastasia traveling through time to befriend a modern-day girl. The ending allows Anastasia and her family to escape and survive, but that is an endnote, not the main plot. These are works written in a time when we know that the Romanovs died and any other alternative is a fantasy. We know that "Anna Anderson" and all the other supposed survivors were frauds. Most people reading these books probably don't even think of the individual person Anna Anderson at all. The mystery has been solved, but the myth endures. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Years ago, I wrote a blog post on the inspirations behind Hans Christian Andersen's "Thumbelina" (1835), examining a theory that the characters were influenced by people Andersen knew. And then I wrote another one a few years after that, focusing on the imagery of tiny flower fairies, which plays a big role in this fairytale. I want to revisit it this topic again and explore a little more deeply. It's always interesting to get into Andersen's writing process because these have become such classic fairytales and there are many different aspects to his stories. "The Little Mermaid," for instance, can be read as a semi-autobiographical tale of unrequited love, but also as Andersen's response to the hyper-popular mermaid story Undine, and also taking influence from other mermaid tales and tropes.

In "Thumbelina," a woman wishes for a little girl, and receives exactly that from a witch. The thumb-sized heroine is then kidnapped by a toad and deals with various talking animals who all want to marry her, until she winds up among fairies exactly her size and finally finds acceptance. Jeffrey and Diana Crone Frank compared Thumbelina to Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) and the short story Micromégas by Voltaire (1752). They also mentioned "the figure of a tiny girl" in one of Andersen's first successful publications, the 1829 story A Journey on Foot from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager. So far as I can tell, this character is the Lyrical Muse, a forlorn, melodramatic spirit of inspiration who appears to the narrator in Chapter 2. When the narrator tries to catch her, she shrinks into a tiny point and escapes through a keyhole. Similarly, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s stories “Princess Brambilla” (1820) and "Master Flea" (1822) both feature imagery of tiny princesses found sleeping inside lotuses or tulips. Hoffmann's work was widely popular in Europe, and in 1828, Andersen was part of a reading group named "The Serapion Brotherhood" after the title of Hoffmann's final book. There's also the Thumbling tale type. I'm sure Andersen came across many of these. There were the Thumbling stories collected by the Brothers Grimm, for instance. These actually do not have a lot in common with Thumbelina. There's the thumb-sized character, born from a wish, who's separated from his parents and swept off on an adventure, but the male Thumblings are typically more proactive and they ultimately return home to their parents. This is very different from Thumbelina, who never sees her mother again in the story, and whose story is something of a coming-of-age, concluding with her wedding and transformation of identity. These characters are also nearly always male. There are female Thumbling characters, but they've all been collected after Thumbelina, like a Spanish character I'd refer to as Garlic Girl (Maria como un Ajo, Cabecita de Ajo, or Baratxuri) and the Palestinian tale Nammūlah (Little Ant). It's more common to have tiny girl characters in other tale types. "Doll i’ the Grass," "Terra Camina," and "Nang Ut" are all examples of the Animal Bride tale, with their sister tales typically being about enchanted frogs, mice and so on. The Corsican "Ditu Migniulellu" is a variant of the Donkeyskin tale, a close neighbor to Cinderella. Thumbelina is the oldest example I've found of a female Thumbling character. Closer is "Tom Thumb," the first fairytale printed in English, and one of the earliest Thumbling variants we know of (depending when you date Issun-boshi). As I mentioned in my post on flower fairies, Tom Thumb was part of a wave of stories around the turn of the 17th century which transformed fairies into tiny, cute flower spirits, changed the face of the English concept of fairies, and has had far-reaching consequences pretty much everywhere. "Tom Thumb" is literary, like "Thumbelina." It gets into tiny detail, describing Tom's wardrobe of plant matter--a major part of the Jacobean flower fairy trope. He is the godson of the fairy queen and makes trips to Fairyland. This story really feels out-of-place among folk Thumbling tales, due to how altered it is - much like Thumbelina. And like Tom Thumb, Thumbelina gets detailed sequences describing her miniature life, like the way she uses a leaf for a boat. There's also a comparison in the way that Tom is accidentally separated from his parents when he's swooped up by a raven, while Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad. (For contrast, in a lot of Thumbling tales, the separation takes place when a human sees the thumb-child and tries to buy him.) The tiny, winged flower fairies whom Thumbelina meets are a direct descendant of the insect-sized, elaborately costumed Jacobean fairies that we meet in "Tom Thumb." Another Andersen tale, "The Steadfast Tin Soldier," also has a Tom Thumb-like bit where the main character is swallowed by a fish and freed when the fish is cut open for cooking. But in addition to Tom Thumb, there's a Danish story that Andersen may have encountered in some shape. This is "Svend Tomling," or Svend Thumbling, which was printed as a chapbook in 1776. Like Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, Svend Tomling is a literary tale. However, it's not focused on the cutesiness of the character; instead it's a lot more ribald, closer to the folk stories and veering off into satire. I'd really need someone fluent in Danish to give more in-depth examination, but my understanding is that like Thumbelina, Svend is created when a childless woman goes to a witch who gives her a magic flower. Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad and carried off in a nutshell; Svend is bought by a man who carries him off in a snuffbox. Thumbelina escapes and rides away on a lilypad drawn by a butterfly; Svend escapes and rides off on a pig. More importantly, Svend Tomling has themes that are unusual for a Thumbling story - a lot like Thumbelina. He contemplates marriage and faces the prospect of unsuitable partners. Thumbelina's suitors are her size, but the wrong species; the human women around Svend are the right species, but the wrong size. Even Issun-boshi feels a little different; it is a romance, but it doesn't feel quite as focused on considering the dilemmas and false matches and societal issues. There is a whole sequence where Svend sits down and debates with his parents about how to find an appropriate wife. Thumbelina faces criticism of her looks, advice on how to marry, and generally societal pressure on how she as a woman should be living her life. Thumbelina and Svend aren't the only Thumblings to assimilate and transform to fit into society (Thumbelina gets fairy wings to live with the fairies, Svend grows to human scale), but it does feel really key. Thumbling stories are often about childhood, albeit exaggerated so that the main character is not merely small but infinitesimal. Most thumbling stories end not with the hero finding a place for himself or getting married, but with him returning to his parents, the place where he still belongs. Tom Thumb dies at the end of his story, leaving him forever a child. Stories like Issun-boshi, where the character literally grows up and gets married, are rarer. References

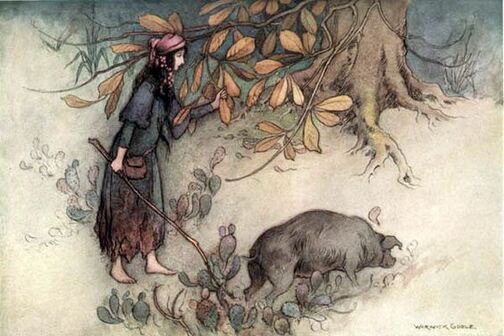

Other Blog Posts The story of "The Golden Mermaid" begins with a tree that bears golden apples. This tree grows in the garden of a King who looks forward to the harvest, but the apples begins to go missing just as they ripen. The King, in desperation, orders his two oldest sons to go out and search the world until they find the thief. His third and youngest son begs to be allowed to go too. The King tries to dissuade him, but the prince begs so much that the King relents and sends him off—although with only a lame old horse. On his way through the woods, the prince meets a starved-looking wolf and offers him his horse to eat. The wolf takes him up on the offer, and the prince then asks the wolf to carry him on his back since his horse is gone.

The wolf is actually a powerful, shapeshifting wizard and happens to know who the apple thief is: a golden bird that is the pet of a neighboring emperor and apparently really likes to escape and steal golden apples. He instructs the prince on how to sneak into the palace and steal the bird. However, the prince clumsily slips up and is caught and thrown into the dungeon. The wolf transforms into a king and goes to visit the emperor. He gets the conversation around to the imprisoned prince-thief and tells the emperor that hanging is too good for such a scoundrel; instead he should be sent off on an impossible task to steal a golden horse from the emperor in the next kingdom. At this point, things turn into a chain of fetch quests. The prince sets out weeping bitterly at his misfortune, only to run into the wolf, who encourages him to go in and steal the horse. Everything will be fine! Everything is not fine, and the prince promptly finds himself beaten up and trapped in Emperor #2’s dungeon after getting caught with the golden horse. The wolf wheels out his same trick, and this time the prince is sent off to capture the golden mermaid. The prince reaches the sea, where the wolf helpfully turns into a boat full of silken merchandise to lure the mermaid in. Turns out she doesn’t really mind being captured once she falls in love with the prince. The Emperors, realizing that the prince has obviously had powerful magical help, quickly give up all claim to the golden mermaid, the golden horse, and the golden bird, and the Prince proceeds home with his whole golden entourage. On their way home, the wolf bids the prince farewell. However, the Prince's two older brothers have heard of his success and are bitterly jealous. They ambush and murder their younger brother, and steal the golden horse and bird; however, the brokenhearted mermaid won't go with them and stays weeping over the Prince's dead body. An unspecified amount of time passes, with the mermaid still weeping over the corpse, before the wolf shows up and tells her to cover the body with leaves and flowers. The wolf breathes over the makeshift grave and restores the prince to life. The three return home, the wicked older brothers are banished, and the prince and the golden mermaid get married. “The Golden Mermaid” is a typical example of the ATU tale type 550, “Bird, Horse and Princess.” Another famous example is the Russian story “Tsarevitch Ivan, the Firebird and the Gray Wolf.” Tales of other types can overlap; there’s ATU 301, known as “The Three Stolen Princesses,” and there are swan maiden-esque tales where the golden bird and the maiden are the same entity, as in “The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples” (from Serbia). The prince is the typical fairy-tale Fool: kind of dumb, but kind-hearted and lucky. We also have the memorable and mysterious wolf magician (helpers in other versions can be foxes, bears or snakes, or sometimes humans under a curse). He's a bit manipulative, but still coaching the clueless prince towards his ultimate success. This character does all the heavy lifting. Shapeshifting into people or inanimate objects? Raising the dead? He’s got it covered. The titular mermaid is probably the most striking thing about this story, but she’s not exactly what modern Western audiences would imagine. She evidently has two legs - see the illustration at the top of this post. This is not so surprising as it might seem; our modern idea of the mermaid with a fish-tail is the result of many years of simplifying and syncretizing and Westernizing. For many cultures around the world, the concept of merpeople - literally, sea-people - could encompass various types of entities and even overlap. And many of those entities would have simply had legs and looked a lot like humans. Think of Greek sea nymphs, the Lady of the Lake and other fairies in Arthurian lore, the Irish tale of the Lady of Gollerus, or "Jullanar of the Sea” in the Thousand and One Nights. Any of these sea people lived in some kind of water realm and could be read as a type of mermaid, yet they don't necessarily have fish tails. This is not the only variant of ATU 550 to include a mermaid; a variant from Slovenia, “Zlata tica” [Golden Bird] features a similar mermaid ("morska deklica") and the trick of catching her attention by selling fine fabric (Janezic, p. 266). The Golden Mermaid has some siren-like attributes, singing and trying to beckon the prince into the water, but fits a lot of feminine stereotypes such as being easily lured with pretty fabric. Still, bear in mind that she's stronger than she might seem to modern readers. In many versions of ATU 550, the heroines are easily carried off by the evil brothers. They continue to weep and can't be comforted, resisting in their own way, but they are as easily stolen as the horse and bird. The golden mermaid is unusual in that she manages to stay with the dead prince and watch over his body. We don't hear how exactly she pulls this off, but she withstands two murderers to do so, something that shouldn't be written off. You may have noticed that in all this, I haven't explained where the story is from. The story appeared in Andrew Lang’s The Green Fairy Book (1892), its most famous and widespread appearance. The Coloured Fairy Book series was published under Andrew Lang's name, but the real minds at work were his wife Nora and a team of mostly female writers and translators. In The Lilac Fairy Book, one of the last few in the long series, Andrew wrote in a preface: "The fairy books have been almost wholly the work of Mrs. Lang, who has translated and adapted them from the French, German, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, Catalan, and other languages." The problem is that, as sprawling and influential as these books are, the citations are frequently awful. Many sources are cut short or just plain missing. Remember “Hans the Mermaid’s Son,” simply noted as “From the Danish.” And “Prunella,” due to the title change and lack of any source, is cut off from its Italian roots. I had to go hunting to find these stories elsewhere. For “The Golden Mermaid,” there is a single terse editor's note: "Grimm." But "The Golden Mermaid" isn't in the Grimms' collections. This may be one of the worst errors ever in the Colored Fairy Books. It looks like the editor mixed up “The Golden Mermaid” with the Grimms’ “The Golden Bird,” a different version of ATU 550. In “The Golden Bird,” the hero is not a prince but a gardener's son, although he does win the kingdom by the end. He’s a little feistier than The Golden Mermaid’s weepy prince, although still hapless (instead of getting caught through clumsiness or happenstance, he’s tripped up by greed or by being too sympathetic to his enemies). The love interest is not a golden mermaid, but the princess of a golden castle, and the wolf-wizard’s role is filled by a talking fox who is secretly the princess’s long-lost brother under a curse. Some scholars don't catch this and refer to the Grimms' Golden Mermaid anyway. The Penguin Book of Mermaids, published in 2019, notes the misleading source with some consternation and even suggests that Lang wrote “The Golden Mermaid" as a very loose adaptation of "The Golden Bird," placing the story with other literary fairy tales. But “The Golden Mermaid” is actually a folktale. I was lucky to stumble across the real source through a tiny note buried in Wikipedia. It's from Wallachia, a historical region of Romania, and was first published in Walachische Maehrchen (1845) by the German brothers Arthur and Albert Schott with the title "das goldene meermädchen" (p. 253). In Romanian, the title translates to “Fata-de-aur-a-mării"; I'm not sure whether this is a back-formation by later scholars, or if the story has been collected in the original language. Arthur collected these stories during a six-year residency in Banat, and considered “The Golden Mermaid” not only the most beautiful story in the collection, but superior to the German “The Golden Bird.” It’s funny reading both of these stories together, because they occasionally seem to fill in gaps of logic for each other, or you can see spots where a story started to stray from the standard plotline. “The Golden Bird” has a few odd fragments, like a random fourth quest tacked on (moving a mountain in order to win the princess). Overall, "The Golden Mermaid" has some interesting themes and characters to unpack, and I especially enjoyed seeing a mermaid in a tale type where they don't often appear. References

Further reading: other fairytales left without sources by Lang Some time ago, a book of collected fairy tale retellings was published. Anyone who picked up this book would have found a nontraditional version of Snow White. The author had written it from the wicked stepmother’s point of view, telling the story of her life. It was also historical fiction, the magical elements replaced with scientific explanations. This is nothing too out of the ordinary for modern readers. This description suits books such as Gregory Maguire’s Mirror, Mirror (2003) or Donna Jo Napoli’s Dark Shimmer (2015).

But the retelling I’m talking about was published in 1782. “Richilde,” by Johann Karl August Musäus, appeared in the first volume of his collection Volksmärchen der Deutschen (Folktales of the Germans). Musäus wrote that he collected these stories from the German folk, but this is not the style of the Brothers Grimm and later folklorists; instead it’s more of the highly literary style of Charles Perrault and Giambattista Basile. It is also the first existing example that we have of the German fairy tale of Snow White, published a generation before the Brothers Grimm got to it. It’s definitely a hefty tale, almost more like a novelette, and the English translation I found was written in older language that takes some getting used to for modern readers. But its ideas and themes fit in strikingly well with modern renditions of the story. Snow White researcher Christine Shojaei Kawan at one point considered this the earliest literary version of the tale, but later apparently had second thoughts as she claims that it doesn't fit with the folktale all that well and can't be considered authentic. There is, for instance, no scene where the Snow White figure has to flee into the wilderness. I would have to agree with Kawan that this is a retelling more than it is a straightforward fairytale. But what a retelling! Honestly, Richilde does not work as a standalone piece. It makes much more sense when understood as a reimagining from the villain’s point of view. From studying "Richilde," it’s clear that Snow White was already very well-known - proving the Brothers Grimm were right when they considered it one of the most popular German fairy tales. As is common for fairy tales, we got elaborate literary adaptations before anyone set to the task of transcribing the original folktales. The fairy tales of Perrault and Basile and the French conteuses are very similar cases, and one of the Grimms' tasks was actually to preserve the folk tales before they could be forgotten and lost in adaptation. But back to the story of Richilde. The tale begins with her birth as the much-wanted child of the Count and Countess of Brabant. She grows up beautiful and, due to realizing from the magic mirror that she’s the fairest girl in the land, extremely vain. It explains how she meets her husband: needing to marry, she asks the mirror to show her the most handsome man in the land. Problem is, he's already married - but not for long, as he is quite flattered by this glamorous younger woman's attentions, and divorces his wife to be with her. The plotline stays mostly with Richilde, leading to some hilarity. When Richilde realizes that her husband’s abandoned daughter Blanca has grown into the fairest maiden in Brabant, she arranges to have her poisoned. But then Blanca keeps popping up alive again, with no explanation, and it’s driving Richilde nuts as she scrambles to fix the situation and figure out what went wrong. I love this scenario so much. There is a mysteriously powerful mirror, created through the mysterious and wise arts of Albertus Magnus (a real historical figure and the subject of many legends), and given to the young Richilde as a gift. The mirror doesn’t talk, but does show images when a rhyming chant is said. In a particularly nice touch, the more evil Richilde’s actions become, the more it rusts until it’s ruined. It’s clearly a magic mirror, complete with moral judgment, but there is at least some handwaving about how it could be Magnus’s practical scientific arts. There are three murder attempts via poison, and the first is an apple or pomegranate with one half poisoned. So it does seem that the poisoned fruit was particularly deep-rooted in German folklore. Although Kawan complained that Richilde fails to hit the correct beats of the full folktale, this is where we have the sympathetic executioner, the equivalent of the fairy tale’s huntsman: Richilde’s Jewish court physician, Sambul, who is tasked with creating these poisoned gifts. Here, the story is surprisingly tolerant for an 18th-century German book, or at least subverts antisemitic expectations. Sambul ultimately turns out to be the real hero of the story. I should be clear that there are still antisemitic elements. It feels especially uncomfortable that Sambul is the victim of the most violence in the story. But as the story nears its ending, it is revealed that Sambul has a strong conscience and has been working against Richilde all along even at the risk of his own life. He substituted harmless sedatives for the poisons, so that Blanca appeared to die but actually woke up a while later. And at the very end, the focus is not on Blanca and her husband’s wedded bliss, but on Sambul being rewarded and going on to live in happiness and prosperity. There is an equivalent to the Grimms’ dwarfs: Blanca, who has been consigned to one of her father’s castles, is attended by court dwarfs. This is another historical twist. These are not mystical woodland or subterranean creatures, but ordinary people, and many historical nobles employed court dwarfs. However, there is still a blurring of lines here. The court dwarfs are apparently skilled smiths and craftsmen, whipping up a coffin with a window - the equivalent of the fairy tale’s glass coffin - and the red-hot iron shoes for Richilde. This hints that these characters were inspired by mythical dwarfs, who were metalworkers in Nordic myth. There is a handsome prince figure: Gottfried of Ardenne, a young nobleman who comes across Blanca’s castle, hears her story, and is at the right time to bring forth a holy relic in an attempt to ward off sorcery just as she wakes up. Richilde attends their wedding having been tricked into thinking that she is the bride, which is a neat little explanation for why she’d be there, and shows her all-encompassing vanity. Before the ceremony, Gottfried tells her of a woman who murdered her daughter out of jealousy, and asks her what punishment is suitable. Richilde, bored and annoyed by what she sees as a delay to her wedding, says that the mother should be forced to dance in burning iron shoes - and then Blanca appears and Richilde realizes to her terror that she has just named her own fate. This scenario of the villain being tricked into choosing their own fate is a classic one, also seen in the fairy tale of “The Goose Girl.” A Danish oral variant of Snow White, "Snehvide," also ends with the stepmother choosing her own execution. In Richilde’s case, her punishment is surprisingly merciful. Instead of dancing until she dies, as in the Grimms’ Snow White, she is only left with burns and blisters on her feet, and people actually put a salve on her feet before throwing her into the dungeon. The Brothers Grimm’s first draft of the Snow White tale was pretty different from the one we currently have - biological mother as villain, biological father as rescuer and breaker of the curse. In many ways, the modern version more closely resembles Richilde. SOURCES

“Ondine’s Curse” is the name of a rare form of apnea, a condition in which people stop breathing. According to various medical texts, it's based on an old Germanic legend - the story of Undine or Ondine, who cursed her faithless lover to stop breathing. Except . . . this doesn't sound anything like the story of Undine, which isn't even exactly a legend. What's going on here?

The Backstory As I've described before on this blog, "undines" originally came from the writings of 16th-century philosopher Paracelsus. The word was evidently his original creation, referring to water elementals or nymphs. Combining the medieval legends of "Melusine," "Peter von Stauffenberg," and various folktales about fairy wives, Paracelsus wrote that undines could gain a soul by marrying a human. However, such relationships were fraught with danger; these water-wives could all too easily be lost to the realm they'd come from, and if the mortal husband took another wife, the water-wife would come back to murder him. This story was passed around and adapted by various authors. Most famously, it found form in the 19th-century novella Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. Undine is a nymph who marries the knight Huldbrand and gains a soul as a result. However, he ditches her for a human lover - which, by the rules of spirits and the otherworld, means he must die. Although Undine still loves him, she is forced to kill him on the night of his second wedding. She appears and embraces him, weeping. "Tears rushed into the knight's eyes, and seemed to surge through his heaving breast, till at length his breathing ceased, and he fell softly back from the beautiful arms of Undine, upon the pillows of his couch—a corpse." Undine then states mournfully, "I have wept him to death." So where did things go off track? This novella became extremely popular, inspiring many adaptations. There were plays, operas, ballets. Even Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid took inspiration from it. One play adaptation, Ondine, by Jean Giraudoux, came out in 1938. In this version, the characters are named Ondine and Hans. Although Hans betrays Ondine with another woman, she still loves him and attempts to stop her people from executing him by running away. However, her efforts are of no avail, and Hans is condemned to death by the king of the water spirits. The former lovers get the chance to say goodbye. The tormented Hans tells Ondine, “Since you went away, I've had to force my body to do things it should do automatically. I no longer see unless I order my eyes to see... I have to control five senses, thirty muscles, even my bones; it's an exhausting stewardship. A moment of inattention, and I will forget to hear, to breathe... He died, they will say, because he got tired of breathing..." As the two share a final kiss, Hans dies and Ondine's memories of him are erased. Losing the Way In 1962, a California-based doctor named John Severinghaus and his colleague Robert Mitchell worked with three patients who all shared similar symptoms. After operations on the brain stem, these patients could not breathe automatically. They had to consciously decide to breathe, and they needed artificial respiration when asleep. Severinghaus and Mitchell wrote a paper about their studies, coining the term "Ondine's Curse" for the phenomenon. They stated briefly: "The syndrome was first described in German legend. The water nymph, Ondine, having been jilted by her mortal husband, took from him all automatic functions, requiring him to remember to breathe. When he finally fell asleep, he died." This is a garbled version of Giraudoux's play. They were clearly inspired by Hans's speech, and as pointed out by researcher Fernando Navarro, they use Giraudoux's spelling, "Ondine." But you can see the play being misunderstood and slanted here, misremembered just a little. Their summary was soon picked up, gaining a life of its own as other medical professionals repeated and mangled it further. Many versions simply repeat some variation on Severinghaus and Mitchell, but we see an emerging image of Ondine as a forceful figure who delivers judgment on her traitorous husband. She, not the ruler of the water spirits, curses Hans. Across various versions, she is angry, a purveyor of revenge or punishment (Navarro 1997). Usually the husband or lover is unnamed, but Hans remains a common moniker (as in Naughton 2006). Some retellings get much more elaborate, with their own mythology. A popular variant explains that if a nymph ever falls in love with a mortal and gives birth to his child, then she will become an ordinary mortal, subject to aging. Nevertheless, the nymph Ondine falls in love with a human, and he with her. One version names him Lawrence (Coren 1997); another calls him Palemon, borrowing from Frederick Ashton's 1958 ballet adaptation Ondine (Mawer 2009). Lawrence/Palemon/whoever swears to her that “My every waking breath shall be my pledge of love and faithfulness to you." However, after she bears his son, Ondine begins to age, and her beauty fades. Her shallow husband dallies with other women. When Ondine catches him in bed with a mistress, she is enraged. With the last of her magic, she calls down a curse which mocks her husband's broken vow: as soon as he falls asleep, he'll stop breathing. Her husband inevitably falls asleep from exhaustion and dies. This variant upends the original worldbuilding. In Fouque’s novel, marriage grants Undine a soul, but she remains otherworldly and powerful. Huldbrand rejects her out of fear and resentment. However, in this variant, marriage transforms Ondine into an ordinary woman, and that's why her husband strays. Some of the shorter retellings are so clumsily phrased that they mix up vital information. One skips over the husband's infidelity: "[T]he beautiful water nymph . . . punished her mortal husband by depriving him of the ability to breathe automatically. Without the benefit of tracheostomy, the poor wretch, having forgotten how to breathe, died in his sleep." (Vaisrub 1978) Another makes Ondine the cheater in the situation! "Ondine, a German water nymph, invoked a curse upon her jilted husband so that he would forget to breathe (and die) when he fell asleep." (Swift 1976, as cited in Navarro 1997) Or was Ondine the one who was cursed? "[T]he water nymph Ondine was punished by the gods after falling in love with a knight by being condemned to stay awake in order to breathe." (BBC 2003) In some versions, Ondine is a succubus-like serial killer: "...a water-spirit of German mythology called Ondine who could cause the death of her victims by stopping their respiration." (Taitz et al 1971, as cited in Navarro 1997) "Ondine was a mythological water nymph who exhausted her human lovers." This author quotes Giraudoux's play, but labels Hans as just "one victim"! (Sege 1992) And sometimes the nature of the curse itself changes to a perpetual sleep, as in one dictionary where Ondine is "A water nymph who caused a human male who loved her to sleep forever." (Firkin 1996) The story goes completely off the rails in one article on spine surgery: "Ondine, a shepherd in Greek mythology, was cursed for his misdeeds by being put into a sleep from which there was no awakening." (Fielding et al, 1975, as cited in Navarro 1997) Critics were rightfully outraged at this summary, which manages to get every single detail wrong. The writers were following blindly in the footsteps of a very confused 1968 article which evidently mixed up Undine with the Greek myth of Endymion. The mistake is so wildly far off that I'm honestly impressed. Conclusion This is what happens when a bunch of people start retelling a story they've never read. The heart of the modern character Undine – carrying through to her spiritual successor, the Little Mermaid – is that she loves her husband. Her love is self-sacrificing and all-forgiving. The medical myth around “Ondine’s Curse” inverts this, making her a vindictive wife, a vampiric seductress, or a sheep-tending Greek man. One article examines the history but concludes lackadaisically, "Whether Ondine kissed or clasped her husband to death depends on the version of the tale, and one can never know who cursed whom" (Tamarin et al, 1989). That's not true, though! This isn't like traditional oral folktales where there really are multiple unique variants and no one can determine an original. This is more like saying that we can never really know whether Dorothy's slippers were silver or ruby in The Wizard of Oz. At what point does urban legend or commonly-repeated misconception become folklore? Can Ondine be considered a myth or legend, as it is often called? Perhaps it has become something of an oral folktale in the medical community. But given that it came specifically from literature, I hesitate to call it that. This is part of a larger issue surrounding the story of Undine. It left its stamp on Western culture, but the work itself has become pretty obscure. For instance, many readers take jabs at Hans Christian Andersen for the theme of souls and salvation in The Little Mermaid, calling it tacked-on or a case of preachy Christian moralizing. But that plotline wasn’t original to Andersen – it was his response to Undine. Scholars such as Oscar Sugar, Ravindra Nannapaneni, and Fernando Navarro have put significant work into tracing the fragmented and confused medical legend of Ondine's Curse. Many of them have argued against using the name at all, calling it a misnomer. From the other side, psychology professor Stanley Coren complained that the term was losing favor because of political correctness and "language sensitivity, where labeling people as suffering from some form of curse is seen as being insensitive rather than colorful." However, Coren says this right after weaving an elaborate summary which bears almost no resemblance to the real story. He also incorrectly attributes the coining of the term to the 1950s. And the vast majority of critics don't complain that it's mean to call a medical syndrome a curse; instead they focus on the fact that the name is fundamentally a bad fit. On the literary level, Ondine neither causes the "curse" nor experiences it, and Hans's experience goes way beyond apnea. You could get pedantic and say "Well, it's named after the play, not the character" but clearly it has not been taken that way. On the medical level, the shifting definitions lead to inconsistency on what the medical condition is. As Nannapaneni et al point out, the name "Ondine's Curse" has come to be used inconsistently for all sorts of conditions related to respiration. Not ideal for a medical term. They suggest that “this wide and nonspecific usage reflects a lack of awareness of the origins of this eponymous term.” These days, the condition is typically known as Congenital Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (CCHS); however, the name "Ondine's Curse" is still around in casual language, and is apparently here to stay. References

Other Blog Posts Syair Bidasari is a story with many parallels to the Brothers Grimm story of Snow White and the worldwide tale type of ATU 709. A syair is a traditional Malay poetry form, and Bidasari is the name of the heroine. Going through it piece by piece, we find many things which seem very different on the surface from Snow White.

We don’t know the date of origin or the author. The oldest extant manuscript dates to the 1810s, with the oldest surviving reference from the previous decade. A similar syair was dated to the 1650s, so this may very well be one of the earliest versions of Snow White that we have today. Julian Millie found that the story was known throughout Southeast Asia, ranging from Indonesia to the Philippines. It was adapted into music and theater, and translations were published in English, German and Russian. Syair Bidasari is an epic poem with intricate language and structure, and it’s been impossible for translators to do it full justice in English. It also keeps going after Bidasari marries the king. See, she was a lost princess adopted as an infant by a kindly merchant. After her wedding, her biological family tracks her down, and there are endless reunions and celebrations and a long digression where her brother slays a monster and marries the princess it was holding captive. (This kind of elaborate runtime is not unfamiliar for old literary fairy tales; compare the original French novella that was Beauty and the Beast, which takes a deep dive into fairy politics and Beauty’s Surprise Secret Backstory as a lost princess. Adaptations immediately dropped that part, with good reason.) Bidasari is not a folktale, but it does seem based on oral tradition. And we can see traces of that tradition continuing in folklore collected much later - in the Indian tales “Princess Aubergine” and “Sodewa Bai,” and the Jewish Egyptian story “The Wonder Child.” These stories vary in some details. “Sodewa Bai” even has a bit of a Cinderella motif, with the prince finding her because of her tiny slipper. But they generally stick to the same plot - this very specific strand of ATU 709. REMOVABLE SOULS One of the most intriguing differences from the European Snow White is how the death-sleep works. European heroines are usually invaded in some way, a foreign body intruding on hers - a bite of apple stuck in Snow White’s throat, a splinter in Talia’s finger. It must be removed in order to awaken her. But in these Asian and Middle-Eastern versions, something is stolen from the heroine and must be returned to her. And here we have the motif of the removable soul. Bidasari’s soul is inside a golden fish, which is nested inside two precious boxes and kept in a pond in her family’s garden. Aubergine’s life is tied to a magical necklace, hidden inside a tiny box, inside a bumble bee, inside a red and green fish. In “Sodewa Bai” the heroine is born with a necklace, in “The Wonder Child” with a glowing jewel; if she doesn’t have her magical item with her, she’ll fall asleep. In all of these cases, the object is worn as a necklace. This resembles ATU 302, "The Giant who had no heart in his body." In these stories, the owner of the removable soul is typically a villain who has nested his heart or life force inside several different things, sometimes animals or insects, sometimes and egg. The hero must seek out the life source to destroy it. It seems like the hero being the one with the removable soul may be common in Indian tales. In "Chundun Rajah" (from the same collector who published "Sodewa Bai"), it's a man who suffers the daily death when his soul-necklace is stolen. Is the soul-necklace in these stories a unique folk tradition variant? Or was the legend affected by the fame of the epic poem adaptation Syair Bidasari? I do find it intriguing that it made it all the way into Jewish storytelling in Egypt. THE VILLAIN A major theme in these stories is the rivalry between two wives. Bidasari faces Queen Lila Sari, who is driven by her fear that the king will marry someone else and lose interest in her. You can feel for Lila Sari at first, when her devoted husband states that he would take another wife if he found someone more beautiful. However, then she turns to torture and murder. (Bidasari, in contrast, holds no deep resentment towards Lila Sari and is content to be one of several wives.) The Punjabi tale of “Princess Aubergine” gets even more horrifying. When the queen tries to magically force Aubergine to confess where her life is kept, Aubergine claims that it is tied to the queen’s son - and the queen promptly murders her own offspring. This continues until the queen has killed all of her own children. Aubergine is attempting to shield herself by appealing to the queen’s maternal instincts and humanity, but the queen has none - weeping afterwards only because she’s enraged that Aubergine still lives. There are particularly strong similarities between “Princess Aubergine,” “Sodewa Bai,” and the 17th-century Italian “Sun, Moon and Talia,” which is also close to Snow White - although the plot is reversed and fragmented, with the enchanted sleep plot wrapped up before the contest with the jealous queen. In all three stories, the villain is an older first wife, and the heroine gives birth to the king's child in her sleep. There's an unspoken focus on fertility. This is especially clear with Talia, who gives birth to twins, while the queen trying to kill her is childless. In “Princess Aubergine,” the queen has seven sons, but she murders them all, effectively becoming anti-fertile. Here, we're starting to see a particular theme becoming prominent - and I want to compare this to what we know about Snow White's villain. A STEPMOTHER OR A RIVAL WIFE? Maria Tatar examined the Snow White tale in The Fairest of Them All: Snow White and 21 Tales of Mothers and Daughters, from the premise that the story is inherently about a rivalry between a beautiful maiden and her cruel mother: a story not only about beauty and aging, but about family dynamics at their most dysfunctional. However, quite a few of the stories Tatar collects are not about mothers and daughters at all. At one point, she notes of Chinese tales that "it is something of a challenge to find stories directly representing mother-daughter conflict" (p. 165). Searching for ancient versions of "Snow White," Graham Anderson wrote that "[c]lose family tensions tend to be toned down in the romances, and their role supplied by external rivals instead" (p. 53). Dropping the "requirement" that Snow White stories must include a wicked mother allowed Anderson to open up the playing field to more stories. But this is begging the question. Who says that close family tension is an inherent part of the folktale? What if the wicked mother is the newer version? We can actually track the development of some Snow White-like tales where it does seem like this is the case: by changing the character relationships, a story of bigamy is transformed into a story of more general jealousy. Charles Perrault's "Sleeping Beauty" is an adaptation of "Sun, Moon, and Talia" where, instead of a rival wife, the evil queen is the king's mother. The villain is also the prince's mother in "The Wonder Child," published in the 1990s, and the prince's stepmother in a 1965 film adaptation of Bidasari. In "Snow White," of course, the villain is a mother (or stepmother) who feels threatened by her daughter's superior beauty. But even in the German versions, this isn't so straightforward as it seems at first glance. In the Grimms' earliest draft, titled "Snow White, or the Unfortunate Child" (the one where Snow White is blonde), not only is the villain Snow White's biological mother, but her father is the one who rescues her. He discovers the glass coffin, grieves over his daughter's "death," and causes her to be woken (he has doctors in his entourage, fortunately). At the end Snow White marries a previously unmentioned prince, and the queen is executed at their wedding. In another variant from the Grimms' notes, the story begins with a count and countess riding through the woods when they encounter the lovely heroine; the count takes her into the carriage with him and the countess becomes instantly jealous. In the earliest versions, the king is an important character, but in the most famous version he has been almost completely erased from the story. Still, commentators have suggested that the magic mirror is a stand-in for the now-absent king, judging between the beauty of his wife and daughter. In stories like these, we start to see a different side to the Snow White tale type: it's not about jealousy over beauty in general, but a contest for the affection of one specific man. In the German "Richilde" (1782), the villain first seduces Blanca's father away from his wife, and then attempts to seduce the Prince Charming figure who's in love with Blanca. Further afield, in "The Hunter and His Sister," a Dagur tale from Mongolia, two women grow jealous of their husband lavishing attention on his sister. And I'm not even getting into the apparent doubling of the jealous mother figure in other tales. In the Italian "The Young Slave" and "Maria, the Wicked Stepmother, and the Seven Robbers" and the Scottish "Gold-Tree and Silver-Tree," the heroine's mother puts her into a death-sleep, and the heroine's lover (or uncle) takes her home only for his mother or wife to awaken her via jealousy or curiosity. Going further afield again: in a search for "Snow White" tales in Africa, Sigrid Schmidt found many tales which showed marks of colonizing European influence, and even some late tales which were directly derived from the Brothers Grimm. Schmidt suggested that a purer African parallel to "Snow White" can be found in the tale type "The Beautiful Girl." It is not the same tale, but its similarities bear noticing. These stories follow a young, innocent girl who is remarkably beautiful. The other local girls become jealous - perhaps especially when a man proposes marriage to her even though she's still too young, or when a group of herdboys point her out as the loveliest. The other girls take her out into the wilderness, where they trap her and leave her for dead. She is later rescued. There is no prince in this story, nor is there a death-sleep, but Schmidt argues that the Beautiful Girl goes through a metaphorical death before being rescued. Also, Schmidt did find versions in which the Beautiful Girl is murdered and later resurrected. Notably, there is no familial relationship between the heroine and the villains. Also, the Beautiful Girl is rescued because people hear her singing (sometimes even in versions where she's dead). Compare this to Syair Bidasari, where Bidasari is able to awaken during the night and tell the king her story. CONCLUSION Syair Bidasari and these other Indian or Middle Eastern tales have their own elements which are quite different from European tales of type 709. Most notable is the consistent motif of the magical necklace containing the heroine's life. However, by comparing and contrasting these with European variants, I suspect we can get a hint of what an ancient version of Snow White may have looked like. What if the most ancient versions of Snow White were something closer to Syair Bidasari - a story where an older woman and a younger woman vie for their husband's attention? From there, it could have split into various versions. In some, the older woman might be the heroine's mother. In others, the older woman might be the love interest's mother. Or there might be a totally different relationship between characters. What do you think? SOURCES

I recently came across an article by Lauren and Alan Dundes stating that Hans Christian Andersen used two famous motifs in his fairytale “The Little Mermaid.” First is the motif of mermaids which, yeah. But second is ATU K1911, “The False Bride.” The authors state that "This second motif, though critical for an understanding of the plot of 'The Little Mermaid' has not received much attention” (56). This article gets more into Freudian analysis, which is not really my thing, but I was really intrigued by the connection from the False Bride motif to The Little Mermaid.

So, in the False Bride motif, the villain steals the heroine’s identity and marries her intended husband. The heroine lives in servitude, in exile, or under a curse. Eventually someone alerts the husband, usually the true bride herself. The false bride is disposed of – often executed in gruesome ways, for instance buried alive or dragged by horses in a barrel full of nails. The true bride then takes her rightful place. This is one of those universal elements that can easily be attached to many wildly varying tales - for instance “The Goose Girl” (ATU 533), “The Three Citrons” (ATU 408) and “The White Bride and the Black One” (ATU 403). In these cases, the swap takes place en route to the wedding. There’s no physical resemblance, but the imposter gets away with it by claiming she’s been transformed, or more often, because it’s an arranged marriage where the betrothed parties have never met. In “Little Brother and Little Sister” (ATU 450) the switch takes place after the wedding, but the impostor is physically transformed to resemble the heroine. In “The Sleeping Prince” (ATU 437), the heroine saves her prince from a Snow White-esque sleeping death. But a villainous servant orchestrates things so that she’s the one present when the prince awakens, so she takes all the credit and marries him. (Note that frequently these stories are inherently racist, ableist and/or classist. Imposter brides are black or Romani, disabled, or of a lower social status. I’m looking particularly at “The Three Citrons” and “The White Bride and the Black One” here.) As I’ve previously discussed, “The Little Mermaid” was especially influenced by the Paracelsus-inspired novella “Undine.” In this 1811 German novella, the husband casts off his water-nymph wife because he's uncomfortable with her magic, and replaces her with a human lover. It's the difference between the two women that's most important to him. But the two women were, in fact, swapped at one point – it’s just that it happened in childhood, not at the wedding. The nymph child Undine was sent to replace the fisherman’s daughter Bertalda, who ended up being raised by a duke and duchess. Andersen has the same love triangle featuring mermaid and human girl, but the approach is very different. The prince has no idea the mermaid exists, or that she saved him from drowning; instead he gives the credit for his rescue to a human girl who found him on the shore. “Yes, you are dear to me,” said the prince; “for you have the best heart, and you are the most devoted to me; you are like a young maiden whom I once saw, but whom I shall never meet again. I was in a ship that was wrecked, and the waves cast me ashore near a holy temple, where several young maidens performed the service. The youngest of them found me on the shore, and saved my life. I saw her but twice, and she is the only one in the world whom I could love; but you are like her." Much like “The Sleeping Prince,” the prince’s mistaken belief is what draws him to this other girl. In this case, though, she’s innocent in this whole debacle. The mermaid is unable to reveal the truth because she is mute. This forced silence resembles “The Goose Girl” or the gender-flipped “The Lord of Lorn and the False Steward,” where the main character is compelled to swear they will tell no one their true identity. It’s also reminiscent of the heroine’s transformation into an animal in “The White Bride and the Black One” or “The Three Citrons.” But there’s no intentional swap going on in “The Little Mermaid,” as there is in “False Bride” tales. Although the physical resemblance between the two girls blurs the lines, the human girl did play a role in the rescue, and the prince’s love for her seems genuine, while he never really sees the mermaid romantically. (He’s still a cad, though.) Ultimately the mermaid chooses to let the prince and his bride live happily ever after, in a self-sacrificial act which shows the story’s moral. However, the Disney adaptation added a happy ending and simplified the cast list by combining two characters – the sea witch who gives the mermaid legs, and the girl who marries the prince. In the process, they gave the story the full False Bride motif. Prince Eric longs for his mysterious rescuer, but doesn’t realize it’s Ariel. Ursula the sea witch takes advantage of this by magically disguising herself to look similar to Ariel. (Also, mind control.) The swap is an intentional act by the villain. Ariel is barred from speaking by the villain, but ultimately gets the opportunity to publicly reveal the truth. False bride Ursula gets a gruesome death, and Ariel regains her identity and marries Eric. Dundes and Dundes make the case that The Little Mermaid, like many of Disney's movies, is unintentionally about the Electra complex, where a girl competes with her mother for her father's affection. I'm simplifying a lot here, but it's gender-swapped Oedipus. According to Dundes and Dundes, the False Bride motif is integral to the story because of the Electra complex, the sexual rivalry between the young Ariel and the older Ursula. You can make a case for Snow White, where the sexual rivalry between mother and daughter is explicit ("Who's the fairest of them all?"), but The Little Mermaid seems like a slim connection. You have to squint to see Ursula as any kind of mother figure to Ariel. Their rivalry is ultimately about political power. And if you go back to Andersen's story, there is no way you can view the mermaid's romantic rival as a mother figure. The False Bride motif itself isn't Electral anyway because it is not ultimately a rivalry between mother and daughter. It's between two peers, or sisters of similar age, or a princess and a servant. So, did Disney insert the Electra complex into The Little Mermaid? I don't think so, because I feel like it's a stretch to identify it that way. This brand of psychoanalysis has been discredited for a long time but does hang around in literary analysis. However, identifying the False Bride motif in Disney's Little Mermaid was a stroke of genius. Sources

Other Posts In the story of "Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp," a sorcerer convinces a young boy, Aladdin, to fetch him a magic lamp from underground cavern. Abandoned in the cave, Aladdin finds himself in possession of a magic ring that summons a genie, and of course the lamp, which summons an even more powerful genie. Aladdin falls for the local princess and orders the lamp-genie to bring her to his chambers at night, then marries her and moves into a magnificent palace built by the lamp-genie. Then the sorcerer steals the lamp back, and Aladdin must recover it. In an epilogue, the sorcerer's brother makes a try for the lamp, but Aladdin wins again. The story was an instant classic, but contains many questions about the nature of genies.