|

Years ago, I wrote a blog post on the inspirations behind Hans Christian Andersen's "Thumbelina" (1835), examining a theory that the characters were influenced by people Andersen knew. And then I wrote another one a few years after that, focusing on the imagery of tiny flower fairies, which plays a big role in this fairytale. I want to revisit it this topic again and explore a little more deeply. It's always interesting to get into Andersen's writing process because these have become such classic fairytales and there are many different aspects to his stories. "The Little Mermaid," for instance, can be read as a semi-autobiographical tale of unrequited love, but also as Andersen's response to the hyper-popular mermaid story Undine, and also taking influence from other mermaid tales and tropes.

In "Thumbelina," a woman wishes for a little girl, and receives exactly that from a witch. The thumb-sized heroine is then kidnapped by a toad and deals with various talking animals who all want to marry her, until she winds up among fairies exactly her size and finally finds acceptance. Jeffrey and Diana Crone Frank compared Thumbelina to Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) and the short story Micromégas by Voltaire (1752). They also mentioned "the figure of a tiny girl" in one of Andersen's first successful publications, the 1829 story A Journey on Foot from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager. So far as I can tell, this character is the Lyrical Muse, a forlorn, melodramatic spirit of inspiration who appears to the narrator in Chapter 2. When the narrator tries to catch her, she shrinks into a tiny point and escapes through a keyhole. Similarly, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s stories “Princess Brambilla” (1820) and "Master Flea" (1822) both feature imagery of tiny princesses found sleeping inside lotuses or tulips. Hoffmann's work was widely popular in Europe, and in 1828, Andersen was part of a reading group named "The Serapion Brotherhood" after the title of Hoffmann's final book. There's also the Thumbling tale type. I'm sure Andersen came across many of these. There were the Thumbling stories collected by the Brothers Grimm, for instance. These actually do not have a lot in common with Thumbelina. There's the thumb-sized character, born from a wish, who's separated from his parents and swept off on an adventure, but the male Thumblings are typically more proactive and they ultimately return home to their parents. This is very different from Thumbelina, who never sees her mother again in the story, and whose story is something of a coming-of-age, concluding with her wedding and transformation of identity. These characters are also nearly always male. There are female Thumbling characters, but they've all been collected after Thumbelina, like a Spanish character I'd refer to as Garlic Girl (Maria como un Ajo, Cabecita de Ajo, or Baratxuri) and the Palestinian tale Nammūlah (Little Ant). It's more common to have tiny girl characters in other tale types. "Doll i’ the Grass," "Terra Camina," and "Nang Ut" are all examples of the Animal Bride tale, with their sister tales typically being about enchanted frogs, mice and so on. The Corsican "Ditu Migniulellu" is a variant of the Donkeyskin tale, a close neighbor to Cinderella. Thumbelina is the oldest example I've found of a female Thumbling character. Closer is "Tom Thumb," the first fairytale printed in English, and one of the earliest Thumbling variants we know of (depending when you date Issun-boshi). As I mentioned in my post on flower fairies, Tom Thumb was part of a wave of stories around the turn of the 17th century which transformed fairies into tiny, cute flower spirits, changed the face of the English concept of fairies, and has had far-reaching consequences pretty much everywhere. "Tom Thumb" is literary, like "Thumbelina." It gets into tiny detail, describing Tom's wardrobe of plant matter--a major part of the Jacobean flower fairy trope. He is the godson of the fairy queen and makes trips to Fairyland. This story really feels out-of-place among folk Thumbling tales, due to how altered it is - much like Thumbelina. And like Tom Thumb, Thumbelina gets detailed sequences describing her miniature life, like the way she uses a leaf for a boat. There's also a comparison in the way that Tom is accidentally separated from his parents when he's swooped up by a raven, while Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad. (For contrast, in a lot of Thumbling tales, the separation takes place when a human sees the thumb-child and tries to buy him.) The tiny, winged flower fairies whom Thumbelina meets are a direct descendant of the insect-sized, elaborately costumed Jacobean fairies that we meet in "Tom Thumb." Another Andersen tale, "The Steadfast Tin Soldier," also has a Tom Thumb-like bit where the main character is swallowed by a fish and freed when the fish is cut open for cooking. But in addition to Tom Thumb, there's a Danish story that Andersen may have encountered in some shape. This is "Svend Tomling," or Svend Thumbling, which was printed as a chapbook in 1776. Like Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, Svend Tomling is a literary tale. However, it's not focused on the cutesiness of the character; instead it's a lot more ribald, closer to the folk stories and veering off into satire. I'd really need someone fluent in Danish to give more in-depth examination, but my understanding is that like Thumbelina, Svend is created when a childless woman goes to a witch who gives her a magic flower. Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad and carried off in a nutshell; Svend is bought by a man who carries him off in a snuffbox. Thumbelina escapes and rides away on a lilypad drawn by a butterfly; Svend escapes and rides off on a pig. More importantly, Svend Tomling has themes that are unusual for a Thumbling story - a lot like Thumbelina. He contemplates marriage and faces the prospect of unsuitable partners. Thumbelina's suitors are her size, but the wrong species; the human women around Svend are the right species, but the wrong size. Even Issun-boshi feels a little different; it is a romance, but it doesn't feel quite as focused on considering the dilemmas and false matches and societal issues. There is a whole sequence where Svend sits down and debates with his parents about how to find an appropriate wife. Thumbelina faces criticism of her looks, advice on how to marry, and generally societal pressure on how she as a woman should be living her life. Thumbelina and Svend aren't the only Thumblings to assimilate and transform to fit into society (Thumbelina gets fairy wings to live with the fairies, Svend grows to human scale), but it does feel really key. Thumbling stories are often about childhood, albeit exaggerated so that the main character is not merely small but infinitesimal. Most thumbling stories end not with the hero finding a place for himself or getting married, but with him returning to his parents, the place where he still belongs. Tom Thumb dies at the end of his story, leaving him forever a child. Stories like Issun-boshi, where the character literally grows up and gets married, are rarer. References

Other Blog Posts

2 Comments

"Swan Lake" and "The Little Mermaid" are the same story.

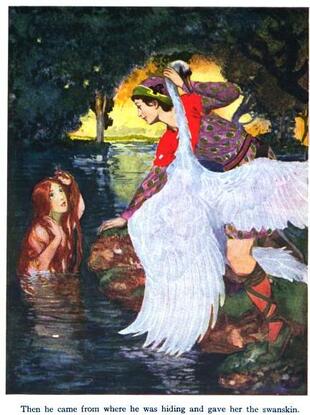

But wait, you may say. The Little Mermaid is a Danish fairytale by Hans Christian Andersen about a mermaid. Swan Lake is a Russian ballet by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, about a princess turned into a swan by a curse. In fact, both stories take inspiration from the Fairy Bride or “Quest for the Lost Bride” tale, categorized as Aarne-Thompson-Uther 400. In the Fairy Bride tale, a man takes an otherworldly creature as a wife. They live together for a while, possibly having children, but one day she leaves him and returns to her own world. This is similar to stories with a mortal woman and supernatural husband, like "Cupid and Psyche" or "East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon." However, while human brides usually get their supernatural husbands back, in ATU 400 - despite the title of "The Quest for the Lost Bride" - it’s less certain that a mortal husband will succeed. Many versions end with him never seeing his fairy wife again. The earliest known example is the Hindu story of Urvasi, found in the Rig Veda (c. 1200 B.C.E.). There are different types of the Fairy Bride story: A) It’s a story of spousal abduction. A man discovers a beautiful maiden - a selkie or swan maiden with a removable animal skin, or a mermaid with a magic cap. He hides the magical garment, trapping her in human form. She inevitably regains the garment and escapes as fast as she can. B) The marriage is consensual, but there is some taboo the husband must not violate (never strike his wife, never spy on her while she’s bathing, etc.). He invariably violates it, and she leaves. The most famous example is Melusine, first appearing in the Roman de Melusine by Jean d'Arras (1393). She marries a man and their union is happy at first; she builds castles for him and bears many sons. But she makes him promise never to look in at her while she's bathing. Inevitably he does so, and sees her as a half-serpent or a mermaid. When he publicly calls her a serpent, she turns into a dragon and flies away. In many versions the idea is that if he had kept his promise, she would have been freed from her curse. There's a related folktale where a young man encounters a woman who's been turned into a serpent or half-serpent by a curse. If he can kiss her three times, she will be freed and he will receive riches and her hand in marriage. Before he can kiss her a third time, he is overcome by fear and runs away. He soon regrets his cowardice, but is never able to find her again. In fact, in some versions this woman is Melusine. The maiden-turned-serpent freed by a kiss appears in many medieval sources. The story gets a tragic, inconclusive ending in The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (14th century) but a happy ending in the French romance Le Bel Inconnu (12th century) and Italian Carduino (14th century). The gender-swapped version would be the medieval story of The Knight of the Swan (tragic ending). In a further variant of B, the taboo is taking another wife. This appeared most prominently in the medieval poem of Peter von Staufenberg (c.1310). Peter's nymph mistress showers him with good fortune but gives him one condition: he must never marry anyone else, or he'll die three days after the wedding. However, other people put pressure on Peter to marry a human woman, with many telling him the nymph is a demon, and he eventually gives in. At his wedding feast, the nymph's leg appears through the ceiling. Three days later, Peter dies. The later story "Melusine im Stollenwald" combines this with Melusine and the Serpent Maiden tales; a man named Sebald promises to kiss Melusine three times to break her curse, but she becomes progressively more serpentine and dragon-like, and his courage fails him. Years later, at his wedding feast to another woman, the ceiling cracks and a drop of poison falls unseen onto Sebald's food. He eats it and dies. A snake tail is seen through the ceiling, implying that the poison is Melusine's venom. Paracelsus, a Swiss philosopher, worked both Melusine's and Peter von Staufenberg's tales into his descriptions of elemental beings in A Book on Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies, and Salamanders, and on the Other Spirits (published in 1566). He dubbed the water elementals "undines." German author Friedrich de la Motte Fouque spun this into a novella, Undine, published in 1811. There's another work that probably inspired Fouque: the successful Viennese play Das Donauweibchen (1798), which follows a knight named Albrecht torn between his mortal wife Bertha and water nymph lover Hulda. The plot is very different from Undine, but the love triangle, setting, and names are similar. Fouque's plot runs as follows: Boy meets water-fairy. A knight named Huldbrand goes traveling through the woods, where he meets and falls in love with the mysterious Undine. It turns out that she’s a water-spirit, and she gains a human soul by marrying him. The fidelity test. Fouque uses two taboos, straight from Paracelsus: first, the husband must never scold his nymph wife near the water or she’ll return to her own world, and second, if he ever takes another wife, the nymph will return and kill him. The doppelganger. Huldbrand reconnects with his first love Bertalda. Bertalda is, in a way, Undine's sister; she’s the long-lost daughter of Undine’s human foster parents. The tragic ending. Huldbrand breaks the first taboo by bringing up Undine's inhuman origins and berating her, causing her to disappear. He then breaks the second taboo by marrying Bertalda. Undine appears after the wedding and drowns him with her tears. When he is buried, she becomes a fountain flowing around his grave. Now we come back to "The Little Mermaid" and "Swan Lake." These stories map onto the same points as Undine. The Little Mermaid We know from Hans Christian Andersen’s letters that he was inspired by Undine when he developed the concept for “The Little Mermaid” (1837). Like Undine, the mermaid is motivated by her desire for a soul. It hits generally the same beats as Fouque's novel: Boy meets water-fairy. The mermaid saves a prince's life and falls for him. The fidelity test. The mermaid can earn a soul by marrying the prince, but if he marries someone else, she will die. The doppelganger. The prince mistakenly attributes his rescue to a human girl who physically resembles the mermaid. The tragic ending. The prince marries the other girl. On the wedding night, the mermaid is given the option to escape death by killing him. She refuses and melts into sea foam, but is resurrected as an air spirit. Swan Lake Around 1870, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky worked on an unsuccessful opera version of Undine. He destroyed most of the score, but recycled part of Undine and Huldbrand’s duet for the music of "Swan Lake," which debuted in 1877. It didn't initially do well, but in 1895 it was brought back and reworked with a simpler plot. Tchaikovsky died shortly before the new version could be completed. Boy meets water-fairy. In the 1877 version, Prince Siegfried hunts some swans until they reach a lake. There he discovers that they are fairy maidens in disguise. Odette, the leader, is the daughter of a knight and a fairy, and is in hiding from her murderous stepmother. Her grandfather, a sorcerer, gave her a magic crown to protect her, and allows her to fly freely in swan form at night. (In the updated 1895 version, Odette and her companions are humans transformed into swans by the evil genie Rothbart - a minor character in the original.) The fidelity test. Marriage will permanently protect Odette from her stepmother. Siegfried promises to marry her. (1895: Siegfried’s oath of love to Odette will break the curse, but if he marries someone else, he dooms her to remain a swan forever.) The doppelganger. Rothbart's daughter Odile, a girl who looks physically identical to Odette (played by the same ballerina). The tragic ending. Siegfried is tricked into proposing to Odile, betraying Odette in the process. Realizing his mistake, he runs back to the lake, where he tears off Odette's crown in an attempt to keep her with him. She dies in his arms and the lake swallows them both. (1895: Instead of the crown scene, Siegfried and Odette drown themselves rather than live without each other. This breaks Rothbart's power.) Inspirations and Themes Swan Lake and The Little Mermaid are not adaptations of the Undine story. They are unique works by modern authors, and Undine was just one of many inspirations behind them. Andersen was familiar with many mermaid stories. "The Little Mermaid" is unusual among the tales listed in this post, because it's entirely from the "fairy bride's" point of view. Her backstory, her feelings about immortal souls, her journey. Unlike Undine or Odette, who depend on their men to complete a test, she bears the knowledge of her test alone; her prince never has any idea what's really going on. The ending of her story, where she refuses to kill the prince, is an intentional reversal of Undine (and, in turn, "Peter von Staufenberg"). Undine easily gains an immortal soul but is still forced to obey her deadly otherworldly nature. The Little Mermaid earns a soul by rejecting that side of herself no matter the cost. "Swan Lake," on the other hand, combines Undine with the traditional swan wife folktale. There are plenty of theories about Tchaikovsky's inspirations, and plenty of European swan-shifter myths. There's the Irish story of the Children of Lir, where the main characters are transformed into swans by their wicked stepmother, and similarly "The Knight of the Swan" which, as already mentioned, has its own similarities to Melusine. (When I first started working on this blog post, the Wikipedia page for Swan Lake claimed that a fairytale called "The White Duck" could have inspired the ballet; however, the stories have nothing in common. I'm not sure where this claim came from and it's been removed anyway at this point, but I wanted to document it for posterity.) A likely influence is Johann Karl August Musäus's 1782 novella "Der geraubte Schleier" or "The Stolen Veil," itself a retelling of the swan maiden folktale. The main character, Friedbert, encounters a hermit named Benno. (“Benno” is the name of Siegfried’s best friend in Swan Lake.) The dying hermit shows him a magical pool, visited occasionally by fairies or nymphs in swan form. The nymphs gain their powers of transformation from golden crowns with attached veils. If a nymph’s crown/veil is stolen, she’ll be trapped in human form. Benno the creepy stalker hermit failed, but Friedbert succeeds in stealing one of the veils. He gives shelter to the stranded swan maiden, Callista, and convinces her to marry him. But when his mother unwittingly exposes his lies and returns the veil, Callista is furious and immediately takes off in swan form. Friedbert searches across the world until he finds her again. Despite her initial anger, she still loves him, and is so impressed by his tireless search for her that she forgives everything. So this is why Siegfried rips off Odette's crown in the original ballet - he is trying to invoke the trope that you can capture a swan maiden by taking her garment. However, Odette's crown was actually protecting both of them. Although it was later edited out, Tchaikovky's twist feels almost like a rebuttal of the way "The Stolen Veil" rewards Friedbert's selfishness. Tchaikovsky was probably also familiar with Russian fairy tales about swans. A different tale type, ATU 313 or "Girl Helps the Hero Flee," often has overlap with swan maiden tales. One example that Tchaikovsky could have encountered was "The Sea Tsar and Vasilissa the Wise" in Alexander Afanasyev's collection of Russian tales, published in the 1850s and 1860s. In this story, a prince spots the Sea Tsar's daughters as they transform from spoonbills into women. He steals the clothing of one princess, Vasilissa; however, unlike the typical fairy bride story, he relents and returns it to her, letting her fly away. Vasilissa later aids him with various magical tasks when he is imprisoned by her father. The Sea Tsar finally allows the prince to choose a bride from among his twelve identical daughters, and Vasilissa leaves clues for the prince to recognize her. Reunited, the prince and Vasilissa return to his kingdom together. In some versions, the prince then breaks a taboo and gets amnesia, and Vasilissa must crash his wedding to another woman so she can trigger his memories. The plot is very different, but notice the (double!) threat of the prince mistakenly marrying a doppelganger. Conclusion Abduction variants of the Fairy Bride tale are about control. Marriages are thinly disguised kidnappings; wives are captives who will take any opportunity to escape. On the other hand, consensual variants are about a test of trust, commitment, or courage. If the male partner passes this test, he can lift the fairy bride to a higher state of existence. Freedom from a curse for Odette, Melusine or the serpent-maiden; a human soul for Undine and the Little Mermaid. It's not a one-and-done test, either; it is long-term. The serpent maiden needs repeated kisses. Undine gets her soul early on, but Huldbrand still needs to continuously honor their vows and be a good husband. Researcher and professor Serinity Young found that the earliest recorded fairy bride stories are of divine women who lift their mortal husbands to a higher state of existence. For instance, the celestial maiden Urvasi promises her husband immortality in heaven. Young proposes that the fairy bride story in its oldest form was about marriage by abduction; Urvasi tells her mortal husband that she was miserable in their marriage, and other early versions similarly focus on the fairy bride's unhappiness and feelings of being trapped. Young suggests that as women lost social status, fairy bride stories were recast in more romantic terms. I wonder if they also blended with a separate story tradition of a cursed beast-bride or snake maiden. In addition to making the male character more sympathetic, the romantic versions also reverse the power dynamic. The mortal man is now the one holding redemptive, transformative power. This culminates in the extreme of "The Little Mermaid," written in a modern Christian European context. The Mermaid is the pursuer in her relationship, going through incredible suffering on her quest, while the prince rejects her as a romantic partner. She is the one seeking both marriage and immortality. However, despite these changes, the mortal man’s fallible nature remains from the older stories. The love rival twist is especially interesting to me. Peter von Staufenberg and Huldbrand bend to societal pressure by marrying human women, taking the easy way out. Swan Lake's Siegfried and the Little Mermaid's prince have a different dilemma. Despite good intentions, they look only at the surface, failing to truly perceive the women they love. SOURCES

Other Blog Posts I recently came across an article by Lauren and Alan Dundes stating that Hans Christian Andersen used two famous motifs in his fairytale “The Little Mermaid.” First is the motif of mermaids which, yeah. But second is ATU K1911, “The False Bride.” The authors state that "This second motif, though critical for an understanding of the plot of 'The Little Mermaid' has not received much attention” (56). This article gets more into Freudian analysis, which is not really my thing, but I was really intrigued by the connection from the False Bride motif to The Little Mermaid.

So, in the False Bride motif, the villain steals the heroine’s identity and marries her intended husband. The heroine lives in servitude, in exile, or under a curse. Eventually someone alerts the husband, usually the true bride herself. The false bride is disposed of – often executed in gruesome ways, for instance buried alive or dragged by horses in a barrel full of nails. The true bride then takes her rightful place. This is one of those universal elements that can easily be attached to many wildly varying tales - for instance “The Goose Girl” (ATU 533), “The Three Citrons” (ATU 408) and “The White Bride and the Black One” (ATU 403). In these cases, the swap takes place en route to the wedding. There’s no physical resemblance, but the imposter gets away with it by claiming she’s been transformed, or more often, because it’s an arranged marriage where the betrothed parties have never met. In “Little Brother and Little Sister” (ATU 450) the switch takes place after the wedding, but the impostor is physically transformed to resemble the heroine. In “The Sleeping Prince” (ATU 437), the heroine saves her prince from a Snow White-esque sleeping death. But a villainous servant orchestrates things so that she’s the one present when the prince awakens, so she takes all the credit and marries him. (Note that frequently these stories are inherently racist, ableist and/or classist. Imposter brides are black or Romani, disabled, or of a lower social status. I’m looking particularly at “The Three Citrons” and “The White Bride and the Black One” here.) As I’ve previously discussed, “The Little Mermaid” was especially influenced by the Paracelsus-inspired novella “Undine.” In this 1811 German novella, the husband casts off his water-nymph wife because he's uncomfortable with her magic, and replaces her with a human lover. It's the difference between the two women that's most important to him. But the two women were, in fact, swapped at one point – it’s just that it happened in childhood, not at the wedding. The nymph child Undine was sent to replace the fisherman’s daughter Bertalda, who ended up being raised by a duke and duchess. Andersen has the same love triangle featuring mermaid and human girl, but the approach is very different. The prince has no idea the mermaid exists, or that she saved him from drowning; instead he gives the credit for his rescue to a human girl who found him on the shore. “Yes, you are dear to me,” said the prince; “for you have the best heart, and you are the most devoted to me; you are like a young maiden whom I once saw, but whom I shall never meet again. I was in a ship that was wrecked, and the waves cast me ashore near a holy temple, where several young maidens performed the service. The youngest of them found me on the shore, and saved my life. I saw her but twice, and she is the only one in the world whom I could love; but you are like her." Much like “The Sleeping Prince,” the prince’s mistaken belief is what draws him to this other girl. In this case, though, she’s innocent in this whole debacle. The mermaid is unable to reveal the truth because she is mute. This forced silence resembles “The Goose Girl” or the gender-flipped “The Lord of Lorn and the False Steward,” where the main character is compelled to swear they will tell no one their true identity. It’s also reminiscent of the heroine’s transformation into an animal in “The White Bride and the Black One” or “The Three Citrons.” But there’s no intentional swap going on in “The Little Mermaid,” as there is in “False Bride” tales. Although the physical resemblance between the two girls blurs the lines, the human girl did play a role in the rescue, and the prince’s love for her seems genuine, while he never really sees the mermaid romantically. (He’s still a cad, though.) Ultimately the mermaid chooses to let the prince and his bride live happily ever after, in a self-sacrificial act which shows the story’s moral. However, the Disney adaptation added a happy ending and simplified the cast list by combining two characters – the sea witch who gives the mermaid legs, and the girl who marries the prince. In the process, they gave the story the full False Bride motif. Prince Eric longs for his mysterious rescuer, but doesn’t realize it’s Ariel. Ursula the sea witch takes advantage of this by magically disguising herself to look similar to Ariel. (Also, mind control.) The swap is an intentional act by the villain. Ariel is barred from speaking by the villain, but ultimately gets the opportunity to publicly reveal the truth. False bride Ursula gets a gruesome death, and Ariel regains her identity and marries Eric. Dundes and Dundes make the case that The Little Mermaid, like many of Disney's movies, is unintentionally about the Electra complex, where a girl competes with her mother for her father's affection. I'm simplifying a lot here, but it's gender-swapped Oedipus. According to Dundes and Dundes, the False Bride motif is integral to the story because of the Electra complex, the sexual rivalry between the young Ariel and the older Ursula. You can make a case for Snow White, where the sexual rivalry between mother and daughter is explicit ("Who's the fairest of them all?"), but The Little Mermaid seems like a slim connection. You have to squint to see Ursula as any kind of mother figure to Ariel. Their rivalry is ultimately about political power. And if you go back to Andersen's story, there is no way you can view the mermaid's romantic rival as a mother figure. The False Bride motif itself isn't Electral anyway because it is not ultimately a rivalry between mother and daughter. It's between two peers, or sisters of similar age, or a princess and a servant. So, did Disney insert the Electra complex into The Little Mermaid? I don't think so, because I feel like it's a stretch to identify it that way. This brand of psychoanalysis has been discredited for a long time but does hang around in literary analysis. However, identifying the False Bride motif in Disney's Little Mermaid was a stroke of genius. Sources

Other Posts The ending of the original Little Mermaid is famously tragic. However, I was startled to discover that not everyone agrees on what that tragic ending was. There are even rumors that the author, Hans Christian Andersen, revised the story after publication and retconned the ending. What is the real ending of The Little Mermaid, and why did Andersen write it the way he did?

The Original Story A mermaid princess rescues a human prince from drowning. Already fascinated by the world of humans, she becomes even more curious after this experience. She learns from her grandmother that although humans are shorter-lived than the mermaids, they have immortal souls; they will go to heaven, while merfolk merely dissolve into sea foam and cease to exist. The only way for a mermaid to get a soul is to marry a human. Enamored of the prince and longing for a soul, the mermaid goes to a sea witch to ask for legs so that she can go on land. The process will be torturous. The mermaid will have her tongue cut out. Although she’ll gain legs, it will be agony to walk. And if she fails and the prince marries someone else, it will mean instant death: “The first morning after he marries another your heart will break, and you will become foam on the crest of the waves.” It's a dangerous gamble, but the mermaid goes through with it. She winds up at the prince’s palace, but he treats her like a small child and is oblivious to her pain. She cannot speak to tell him who she is, and he marries another woman. On the wedding night, the mermaid’s family gives her a knife; if she kills the prince, she can escape death and return to her old existence in the sea. Still no soul, but at least she’ll survive. However, the mermaid refuses. She leaps into the ocean to become sea foam, but unexpectedly, she is resurrected as one of the Daughters of the Air. Like merfolk, these spirits have three-hundred-year lifespans; unlike merfolk, they have the chance to earn souls and continue to Heaven. The tale ends with the explanation that children’s good behavior shortens the air-spirits’ time of wandering, and bad behavior lengthens it. Behind the Story Although The Little Mermaid is an original story, it was informed by older folktales and literature. In medieval stories like Melusine or traditional folktales like "The Lady of Llyn y Fan Fach," a human man marries a water sprite. However, he breaks some taboo - spies on her, scolds her, or hits her. She then vanishes forever, leaving him and their children behind. In the 14th-century poem "Peter von Staufenberg," a man marries a fairy who bestows fortune on him - but when he breaks his vows and weds a human princess, the fairy causes his death. These stories inspired the Swiss philosopher Paracelsus. He wrote about his cosmology of elemental beings, where water elementals were called nymphs, melusines, or undines. In Paracelsus' work, an undine who marries a human will gain a soul, and any children born of their union will also have souls. However, if the husband ever rebukes his wife while they're on water, she will vanish forever. And if he marries someone else, the undine will kill him. Paracelsus directly referenced Peter von Staufenberg. Paracelsus' elementals were widely influential. Among other things, they inspired a novella published in 1811: Undine, by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. The titular Undine is a water spirit. When she marries a human knight, she immediately gains a soul and transforms from a capricious sprite to a docile, affectionate bride. However, her husband feels deeply disturbed when he learns of Undine’s origins. Falling for another woman, he rejects Undine and she vanishes back into the water. When he is about to be married, Undine returns and unwillingly bestows a kiss of death on him. She grieves at his funeral and fades away, leaving only a fountain in her place. There were quite a few other stories about mermaids popular in the early 1800s. B. S. Ingemann's De Underjordiske (The Subterraneans, 1817) included a mermaid who would turn into sea foam if she didn’t marry a human man. Hans Christian Andersen was familiar with all of these, as well as the German story of Lorelei the siren. These inspirations showed up in Andersen's work long before The Little Mermaid. His 1831 book Skyggebilleder (Shadow Pictures) mentions that "the legend says, that the mermaid alone can receive an immortal soul from man's true love and Christian baptism" (Wullschlager 111). Also in 1831, Andersen published a poem titled "Havfruen ved Samsøe," which features a three-hundred-year-old mermaid dissolving into foam. He worked on another poem called Agnete and the Merman, based on a ballad about a human woman who abandons her merman husband and children. (Wullschlager 124) However, the Little Mermaid was a direct response to Undine in particular. Andersen wrote to a friend in a letter dated February 1837, "I have not, like de la Motte Fouquet in Undine, let the mermaid's gaining an immortal soul depend on a stranger, on the love of another person. It is definitely the wrong thing to do. It would make it a matter of chance and I'm not going to accept that in this world. I have let my mermaid take a more natural, divine path." Critical Response Ever since publication, some critics have skewered the ending. The most frequent description is “tacked-on"; also artificial, forced, or false. To these critics, The Little Mermaid is a tragedy of unrequited love. The happy ending doesn’t fit (especially since it serves up the entirely unforeshadowed Daughters of the Air and some pompous moralizing). Phyllis M. Pickard dismissed the salvation plotline as "a mist of mysticism utterly unsuitable for children". And a 1908 edition of Forum called Andersen’s ending a “compassionate lie.” Even though he was the author, they felt so strongly that his text was flawed, that they rejected it outright. Andersen had written the wrong ending. The mermaid needed to die. However, a growing number of critics have pushed back, arguing that the ending of The Little Mermaid is an organic part of the story. It isn't just about unrequited love; it's a story about salvation and spirituality. Again, this was Andersen's direct response to a longer tradition of soulless mermaids. The Little Mermaid is fascinated by the surface world and feels out-of-place among merfolk before she ever sets eyes on the prince. She is deeply distressed to learn that she will one day cease to exist, while humans will continue on to eternal life. Yes, she loves the prince, but her quest for a soul is also an inextricable part of the story. At the climax, her two motivations clash. She must choose between her love for the prince and her fear of death. Her selfless choice earns her a third option: the Daughters of the Air. It is a bittersweet ending; she doesn't marry the man she loves, and she still faces a long road to Heaven, but her death is not final. You can see a similar ending in Andersen's 1858 tale "The Marsh King's Daughter," which also has the main character dissolve and die - it may seem sudden, except that the character's longing for Heaven has been foreshadowed. The Little Mermaid was clearly very meaningful to Andersen. He once wrote, "it's the only one of my works that moved me as I wrote it." Many scholars have connected the plot to Andersen’s pining for his friend Edvard Collin, whose wedding took place the same year that Andersen wrote this story. Biographer Jackie Wullschlager suggested that The Little Mermaid symbolized Andersen’s way of coping. Although he could not be with Collin, he could focus on building an enduring legacy through his writing. The mermaid will never gain a soul from the prince or have children with him, but she will find another way to immortality. (Wullschlager 174-175) An Alternate Ending? A commenter to this blog mentioned hearing about Andersen writing an alternate ending. This sounded vaguely familiar. When I looked into this, I found a few mentions around the Internet indicating that Andersen had revised the story after publication. According to the rumor, the story was originally even bleaker, ending with the mermaid melting into sea foam. Only later were the Daughters of the Air added, in order to soften the story for children. This rumor is false. Of course, we don’t have every single draft that Andersen worked on during development. However, plenty of scholars have studied Andersen’s work, and there’s nothing to support the retconned-ending rumor. Here’s what we know: Andersen began planning "The Little Mermaid" by at least 1836. The first known working title was "Luftens Døttre" - The Daughters of the Air. Andersen later called the story "Havets Døttre," The Daughters of the Sea. Although the title seems to have changed multiple times, the air spirits were part of the story from very early on. The manuscript was completed on 23 January 1837. Andersen's letter about his mermaid earning her own soul was dated 11 February 1837, less than a month later. "The Little Mermaid" first appeared in print in April 1837, in the first collection of Eventyr, fortalte for Børn (Fairy Tales Told for Children). In the preface, Andersen wrote that The Little Mermaid's "deeper meaning" might appeal best to adults - but "I dare presume, however, that the child will also enjoy it and that the denouement itself... will grip the child" (Johansen p. 239) The story soon appeared in additional collections: Eventyr (Fairy Tales) in 1850, and Eventyr og Historier (Fairy Tales and Stories) in 1862. All of these versions have the same ending with the Daughters of the Air. There is no retconned "original ending." In fact, the original ending from the manuscript was shortened. The draft featured more dialogue from the mermaid: "I myself shall strive to win an immortal soul . . . that in the world beyond I may be reunited with him to whom I gave my whole heart." (Wullschlager 168) I wonder if the original, longer section might have made the Daughters of the Air ending feel less abrupt to critics. But to complicate matters, some people do remember reading versions where the mermaid simply dies. One such version appears in the 1973 book Disney's Wonderful World of Knowledge, Volume 14 – translated from the Italian Enciclopedia Disney by Elisa Penna. It is a very short, almost summarized version, but the ending has significant changes. In Penna's version, the mermaid is about to kill the prince when he wakes up and innocently asks her what's going on. At his words, she repents. The whole interaction is transformed, making the mermaid morally ambiguous and giving the prince more agency. It ends like so: She fled from the room, knowing that she must soon die. By dawn, she felt the change coming on. Just as the witch had threatened, she was turning into foam--the beautiful white foam that caps the waves as they roll over the endless blue sea. (This means that Disney went darker than Andersen. Try that one on for size.) And another, Lucy Kinkaid's The Little Mermaid (1994) for beginning readers: The little mermaid looks at the sleeping prince. She cannot harm him. She would rather die herself. The little mermaid throws the knife into the sea. Then she throws herself into the sea. She changes into sparkling foam and is never seen again. There were also summaries which focused on the tragedy, and left out the more convoluted bittersweet ending. In the 1923 book Nobody's Island, a character remarks that the little mermaid "didn't marry the Prince, and... on the night of his marriage with another she faded away and passed into the foam of the sea." I knew that many storybook retellings softened the ending in a Disney-like way, but I hadn’t realized that some went the other direction and killed off the mermaid permanently. As already noted, many critics disliked Andersen’s ending. It seems that some storytellers also felt the need to leave the story as a tragedy. The rumor that Andersen rewrote his ending may have arisen for a number of reasons.

The rumor is easily debunked, but I would also argue that the ending of The Little Mermaid is not tacked on either literally or metaphorically. It is a natural part of the story. It was not added after the fact. This should be clear from Andersen's life, his inspirations, and his spirituality. It's also fascinating how The Little Mermaid was a response to Undine. Later stories, like Oscar Wilde's "The Fisherman and His Soul" and Disney's Little Mermaid, responded in turn with different spins on the subject. It's an evolving conversation. (Edited 7/14/23 with page number correction) Sources

Other Posts Hans Christian Andersen's tale of "The Marsh King's Daughter" (1858) follows Helga, the daughter of a monster and a kidnapped princess. During the day she is beautiful like her mother but violent and cruel; during the night, she is hideous like her father but sad and gentle. There are heavy Christian themes, with Helga meeting a noble missionary priest and breaking free of her curse through the power of God. At the end, Helga and her mother return to Egypt. Helga is about to be married to a prince, but seems distracted from her impending wedding. She has spent a lot of time meditating on Christianity and the now-dead priest who saved her. She prays for a glimpse of Heaven and is allowed to see its glory for three minutes. When she returns, however, she learns that "many hundred years" have passed since she vanished on her wedding day. Upon hearing this, her body crumbles to dust, freeing her to return to Heaven.

This story always pulled me in at the beginning with its concept and descriptions, but the ending was just depressing. Yes, Helga’s greatest desire is to go to heaven, but I still found the ending dissatisfying and discomfiting. There's just something freaky about your heroine going all Infinity War at the end. And I say this as someone who grew up loving stories of martyrs and saints. Andersen, as usual, pulled in a lot of fairy tale concepts. The beginning is very familiar, with a group of swan maidens taking off their feathery cloaks to bathe, and a man who captures and forcibly marries one of them. However, this trope usually features a human man winning a supernatural bride. In this case, the swan maidens are human princesses and the man is a literal swamp monster. And the ending of Helga's story is a popular medieval legend. In fact, that legend is a fairy motif repackaged by Christian storytellers. This motif has been incredibly widespread from ancient times up to modern literary tales like Rip Van Winkle. Urashima Tarō, a Japanese tale dating back to the 8th century, centers around a fisherman named Urashima who catches a turtle which turns out to be a princess of the sea. She takes him away to her blissful underwater kingdom, where he has eternal life and everything he could ever want. What he wants, though, is to visit his old home on land. He arrives only to find that centuries have passed and everything he knew is gone. The ending varies, but generally all of his years come upon him at once and he is left an old man, his immortality gone. And in The Voyage of Bran from Ireland, also from around the 8th century, much the same thing happens. After seeing a beautiful silver branch, Bran sets out for the Land of Women, the utopian island where the branch grew. He and his men live there for what seems like a year, feasting and totally happy, but one of them feels homesick. The band returns to Ireland briefly, and learns that centuries have passed and they are remembered only as legends. The homesick man steps onto dry land and turns to dust, and his companions decide they'd better book it back to the Land of Women. King Herla, an English character from the 12th century, had the same experience after dealing with a dwarf king. And in a 12th- or 13th-century lai, the knight Guingamor (just like Urashima and Bran) immediately regrets leaving his supernatural sweetheart. The moral in Urashima and Bran's tales is to not break taboos. In both cases, a man ignores the commands of his lover (who is basically a goddess) and dooms himself to a terrible punishment. King Herla's post-Christian story has the moral that the supernatural creatures of older religions are treacherous and evil. Herla is punished for having anything to do with the fae. In medieval times, the story got repurposed. The land of joy and immortality was replaced by a Christian Paradise. Often, the hero of this story was a monk or bishop. The story was used to illustrate the idea that Heaven is so wonderful that a thousand years there are like three minutes, and earthly life is nothing compared to it. The main character would return long enough for people to confirm his identity and be amazed by the miracle, before he disintegrates and joyfully returns to Heaven for good. The main idea of the story is that eternity will not be boring, an issue which has apparently nagged at people for a long time. Versions appeared in English, Spanish, Slovenian, you name it. A fourteenth-century Italian legend featured four monks who, like Bran, went off seeking Paradise after finding a wondrous tree branch from that location (MacCulloch, Medieval Faith and Fable, p. 199). The most widespread version, where a bishop is entranced by the song of an angelic bird, appeared in a homily by the 12th-century French bishop Jacques de Vitry. At the same time, interestingly, the story has survived with fairy roots intact. For instance, a Welsh story of a farmboy who sits under a tree listening to a bird’s entrancing music parallels the story of the bishop. Despite the similarities, it's clear that the bird in the Welsh fairytale is from a very different otherworld than Heaven. (Howells, Cambrian Superstitions) Hans Christian Andersen may have been particularly inspired by something close to home: the Danish tale of "The Aged Bride." Published in Benjamin Thorpe's Northern Mythology (1851), it follows a bride who steps out of a dance at her wedding and notices elves celebrating in a nearby field. When she approaches, they offer her wine and invite her to join in their dance. Completing the dance, she remembers her husband and hurries home. There, however, she finds herself in a situation identical to Helga's, Urashima's, and Rip Van Winkle's. The wedding party has vanished and the town looks completely different. No one recognizes her except as an old story from a hundred years ago. Upon hearing this, she falls down dead. Compared to this story illustrating the dangers of the fairy world, "The Marsh King's Daughter" is positively cheery. Further Reading

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed