|

There was no real concerted effort to start recording folktales until about the 19th century. However, collectors like the Grimms insisted that their stories were ancient. They were recording traditions that went far back into history. However, the school of thought later drifted towards the idea that the stories were all fairly modern. However, this has now switched course. During one period, some folklorists fell into the trap of drawing similarities based on surface resemblances. Tom Thumb and Tam Lin have similar names, so they must have originally been the same character. Shakespeare's tiny fairy Mab and the Irish goddess Medb are visually similar names, so they must be the same character. (Never mind that Medb is pronounced more like Meave.) But what we should really look at are the elements of the story. The Italian story of Giovanuzza the Fox includes neither cat nor footwear, but it's clearly the same story as Puss in Boots. It's possible to have a Red Riding Hood tale with no mention of the iconic red hood. Instead of a wolf, there could be a tiger. Sara Graça da Silva and Jamshid J. Tehrani, in their study of ancient fairytales, suggest that Red Riding Hood and the story of the Seven Kids share a common ancestor. Aglaia Starostina identified stories from a 9th-century Chinese manuscript as analogues of Sleeping Beauty. Spindles and shuttles? No. A young woman fated to "die" only to be revived? Yes. Syair Bidasari, a Malay poem probably from around 1750, has similarities to Snow White. Scholars also find fairy tale motifs buried in ancient mythology. Iona and Peter Opie, in Classic Fairy Tales, compared Red Riding Hood's dialogue with the wolf ("What big eyes you have, Grandma!" "All the better to see you with") to the story of Thor and the giants in the Elder Edda, where he impersonates a bride in order to steal back his hammer. "Why are Freyja's eyes so ghastly?" asks Thrym, catching a glimpse of them beneath her veil. "It is because she has had such a longing to see you," replies Loki, "she has had no sleep for eight nights." My go-to fairytale, Tom Thumb, is hard to trace back before, well, "Tom Thumb," a 17th-century British chapbook. However, elements go back far into the history of storytelling. The Greek myth of Kronos and the story of Jonah both describe a person being swallowed but surviving and escaping. The Greek god Hermes, much like Thumbling, starts driving cattle on the very day he's born. Japanese mythology has the tiny god Sukunahikona (appearing in the Kojiki, possibly the oldest surviving Japanese literary work), and the legend of Princess Kaguya, a tiny baby girl discovered by a childless couple. This--and the Japanese version of Tom Thumb, Issun-boshi, also being very old--makes me wonder if the story originated in Asia. Graham Anderson's Fairytale in the Ancient World looks specifically for fairytale motifs appearing in ancient myths. Anderson mentions a scene in Petronius' Satyricon, a novel from the 1st century AD, where someone remarks, "the man who was once a frog is now king." That seems like a reference to the Frog Prince. Anderson finds ancient connections to Cinderella, Snow White, Beauty and the Beast, Rumpelstiltskin, and many other stories. In some cases, the connections feel like a stretch - like pulling together different strands of Greek myth to suggest that a nymph named Chione (Snow) was an early Snow White and Artemis played the part of her murderous stepmother. In others, there are some compelling coincidences. In a 2nd-century Greek novel, a convoluted tale features a woman named Anthia (flower) who fakes her death, and Anderson suggests that this was a pragmatic adaptation of Snow White. A few people have sent me links to Da Silva and Tehrani's study, and it is fascinating - although it took me forever to figure out what they were actually doing, and I may still be grossly oversimplifying it. They used phylogenetics, the study of language. If two different languages both have an example of, say, Hansel and Gretel, then there's a good chance that you can trace the story back to the nearest common ancestor of both languages. The farther back that common ancestor, the older the tale. The story they trace back the furthest is ATU 330, ‘The Smith and the Devil,' possibly existing as far back as the Bronze Age. In this story, a smith makes a deal for his soul with an evil being, but then tricks the being. That feels like guesswork to me. Still, you need some guesswork when dealing with oral tales that were not written down until centuries later. This study has been criticized for biases and a sample size which is much too small and Europe-centric (see the letter by D'Huy et al). However, the authors responded to say they were aware of the limited sample size and had acknowledged this shortcoming in their paper, arguing that critics overlooked their actual points. Another tale that has been pointed out by other scholars as particularly ancient (in that they can trace back recorded versions to Ancient Egypt) is the "Tale of Two Brothers." Sources

0 Comments

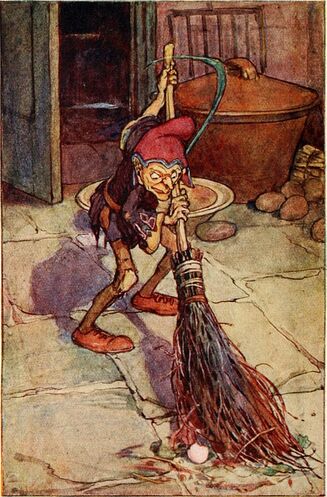

Brownies and boggarts are both terms for household spirits, fairies that haunt the home. And sometimes, they're one and the same. An angered brownie will stop cleaning and doing chores around the house, and become a boggart, causing mischief and destruction. I happen to like this idea... but is it accurate?

In folklore, there are many classes of spirits, including household spirits. There are brownies, hobgoblins, hobs, kobolds, dobbies, silkies, and countless others. They are usually benevolent, helping around the house as long as they are discreetly rewarded with a simple bowl of milk or other food. Clothing is a more perilous gift and usually results in them leaving. (This is where you get "Master has given Dobby a sock!") Boggarts are a wilder variation. They are close to bogeymen - notice that "bog" root syllable, related to "bug," "pug," "puck" and "pooka." Some haunt outdoor places. Others are attached to particular houses and families, and behave like poltergeists. Like other house spirits, they are frequently the ghosts of the deceased. House-spirits could absolutely change with the tides. The German house-spirit or kobold, Hinzelmann, was helpful and playful (although with a mischievous streak), but sometimes behaved as a poltergeist - driving off suitors who visited the family's daughters, for instance. Another, Hödeken, was "kind and obliging" but also strangled an insolent servant boy and cooked him into a soup. From there on, he became so violent that he had to be exorcised. And still another, Goldemar or Vollmar, had a similar escapade of cooking and devouring a human who insulted him. In a Danish family of tales like "The Nis and the Boy," a house-spirit called a nis has an ongoing rivalry with a boy who mocked him. This is ATU Type 7010, The House-Fairy's Revenge for Being Teased. In "The Penitent Nis," the nis believes that the humans neglected to put butter in his offering of porridge, so he kills their cow. However, he then finds butter at the bottom of his bowl. To make things right, he leaves treasure in the barn. The same thing happens in the Swedish tale "The Missing Butter," except that here the tomte steals a cow from the neighbors to replace the one he killed. In Popular Tales of the West Highlands vol. 2, there is a story of a "bauchan" which annoyed and tormented a man named Callum, but which also often aided him. It might steal a prized handkerchief or cause other trouble, but was always helpful in a pinch. It brought a load of much-needed firewood through a snowstorm, and accompanied Callum to America and helped him start a farm there (pp. 91-93). In British Goblins, Wirt Sikes - discussing the household goblin called the Bwbach - remarks that "The same confusion in outlines which exists regarding our own Bogie and Hobgoblin gives the Bwbach a double character, as a household fairy and as a terrifying phantom." Even Shakespeare’s Puck, Robin Goodfellow, or Hobgoblin fits this description. Puck is best known for his mischief and messes – he “frights the maidens,” keeps butter from churning or beer from foaming, and “mislead[s] night-wanderers, laughing at their harm.” But he also bestows good luck and does housework: "I am sent with broom before, to sweep the dust behind the door." These traits were common for Puck or Robin Goodfellow whenever he appeared in chapbooks and ballads around this era. He’s equal parts will o’ the wisp, bogeyman, poltergeist and brownie. But those are all different house spirits from different countries. The theme here was brownies and boggarts. Despite often being ghosts and monsters, boggarts could be benevolent in their role as house-spirit. Lancashire Folk-lore (1882) mentions the "Boggart of Hackensall Hall," who appears as a horse. It did all the chores, but if a warm fire was not lit on the hearth for it, it became furious and noisy. In Howard Pyle's story "Farmer Griggs's Boggart" (1885), a boggart is "a small imp that lives in a man's house... doing a little good and much harm." Here, a boggart enters the house and gains the family's welcome by promising to do the housework, and at least at first, he really does help. Only later does his true malevolent nature rear its head. Nor were brownies always good. John Brand wrote in 1703 that "Not above forty or fifty years ago, every family had a brownie, or evil spirit." Katharine Briggs mentioned a Scottish tale in which a human girl kills a sinister brownie, and is in turn killed by his mother Maggie Moloch. Meg Mullach has elsewhere been recorded as a brownie's name. There is also a tale where a greedy farmer fired some of his staff, and Maggie became destructive and mischievous until he hired them back. Why the connection specifically from brownies to boggarts? Maybe it's the alliterative sound. They lend themselves to association. In the same way, the similar "bogles" were mentioned alongside brownies in early fairy-related literature. In the preface to the Eneados, his translation of Virgil's Aeneid, the Scottish bishop Gawain Douglas wrote "Of brownyis and of bogillis faill this buke" - "of brownies and bogles full is this book." That was in 1513. Similarly, in Polwart's Last Flyting Against Montgomery (c. 1580s), we hear of "Bogles, Brownies, Gyre-carlings, and Gaists." In Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, Volume 2, John Rhys calls the "Bwca'r Trwyn" (Bwca of the Nose) "both brownie and bogie in one." "Bogie" is the Welsh equivalent of "boggart." It follows a bwca, or house spirit, who becomes troublesome after his favorite human leaves and must be exorcised. concludes that "the brownie and the bogie reduce themselves here into different humours of the same uncanny being." I.e., there's overlap between two similar classes of fairy here. He adds, however, "Their appearance may be said to have differed . . . the bogie had a very long nose, while the brownie of Blednoch had only 'a hole where a nose should hae been.'" Rhys also told a story where a servant girl, as a prank, put stale urine into the milk left out for the household's benevolent bwca. At this trick, he grew enraged and beat her, then left forever. (Rhys 593-594). The English folklorist Katharine Mary Briggs seems to have been interested in this particular tale type of brownies gone bad. In The Personnel of Fairyland (1953), she collected a tale near-identical to that of the Bwca'r Trwyn, and titled it "From Brownie to Boggart." Here we are at last: brownies and boggarts explicitly identified as the same thing. "...as a dog will sometimes grow mischievous and morose when it is unhappy, so the brownie gave himself over more and more to mischief until he was no better than a boggart." Briggs' titular character, fallen from house-cleaning grace, wreaks havoc with the farm animals, smashes dishes, and makes noise all night. Briggs throws in a unique description, telling us that the brownie "even grew a boggart's long, sharp nose." In this book, Briggs was trying to establish various classes of fairy, and she selected certain names for those classes. Plenty of folklorists have done this as they tried to classify fae. In Briggsian taxonomy, it is simply that good house spirits are "brownies" and bad house spirits are "boggarts." She was hardly the first to use "brownie" as a classification. Callum's bauchan, in 1860, was "a regular brownie." The story of Bwca'r Trwyn, with its brownies and bogies, was published in 1901. Briggs does, however, seem pivotal in pairing brownies with boggarts specificially. Her taxonomy shows up in her other books and articles as well. In The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, she identifies a ghostly "Silkie" who went from benevolent to poltergeisty as a case where a "Brownie had turned into a Boggart." As always, with stuff of this nature, popular culture both feeds on it and influences it. Juliana Horatia Ewing published a story titled "The Brownies" in 1865, which inspired the girl's club name. According to Ewing: "The Brownies, or, as they are sometimes called, the Small Folk, the Little People, or the Good People, are a race of tiny beings who domesticate themselves in a house of which some grown-up human being pays the rent and taxes. . . They are little people, and can only do little things. When they are idle and mischievous, they are called Boggarts, and are a curse to the house they live in. When they are useful and considerate, they are Brownies, and are a much-coveted blessing." It ultimately turns out that human children are the "brownies" and "boggarts." I remember being disappointed when I read it as a child, since it was sadly lacking in actual magic and turned out to just be a moral tale. I think Ewing may indeed be the driving force here. I am not sure whether she originated this idea, but she definitely pushed it into the public eye. This story inspired the girls' club name, for one thing. It could have influenced Katharine Briggs as she picked out the names of her fairy classes. The Spiderwick Chronicles, by Tony DiTerlizzi and Holly Black, newly popularized the alter-ego approach. Thimbletack the brownie and sometime boggart first appeared in The Field Guide, published May 2003. The film adaptation made this even more explicit. Thimbletack would hulk out into a larger green version of himself, but could be instantly calmed down with food. Another author who takes this tack is Mark Del Franco in his books Skin Deep (2009), Unperfect Souls (2010), and Face Off (2010), in which brownies are capable of temporarily "going boggart." It seems to be like entering a manic state and can happen easily, swapping between helpful and industrious and absolutely crazed. So are brownies and boggarts the same thing? As shown here, many stories show an angry house-spirit turn violent. Even the most benevolent fairy beings are still dangerous. However, I'd caution against sweeping claims that brownies and boggarts are traditionally two sides of the same coin. As far as I'm concerned, brownies and boggarts specifically are entirely separate ideas from different sources. A boggart is an English term dating to around the 1560s. A brownie is an originally Scottish term dating to around the 1510s. Juliana Horatia Ewing popularized them as two names for a Jekyll-and-Hyde-style creature, and Katharine Briggs continued that. In folklore, you're more likely to find brownies, boggarts, kobolds, nisses, tomten, bogies and other beings that are simply ambiguous, capable of help or mischief without changing their names or appearances. Insult was the best way to turn a house spirit vindictive and cruel, but they also seemed to turn mischievous when left idle and bored. As Wirt Sikes said, these creatures - whatever they were called and wherever they showed up - always had a double nature. And they didn't need a double name. One name was enough to encompass both sides of their blurred identity. The alter-ego boggart is still a cool idea. It's one of those concepts that is genuinely fun, so it gets adopted into more and more adaptations of folklore. One of my own stories-in-progress features brownies who transform into boggarts. Sources

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed