|

In “Cupid and Psyche” and “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon”, the heroine breaks a taboo, loses her husband, and has to travel the world and complete daunting tasks to find him - but she does eventually win him back.

In “Beauty and the Beast,” Beauty returns home to visit her family, but stays too long (forgetting the Beast's instructions and thus breaking a taboo). The Beast nearly dies due to her absence, but she returns just in time to swear her love. This revives him and breaks his curse. But there are a couple of versions that don’t end so happily. One is “The Ram,” a French literary tale by Madame D’Aulnoy (1697). This story resonates with many different fairy tales. Returning from war, a king greets his three daughters and asks about the color of their dresses. The first two say that the color represents their joy at his return, but the youngest, Merveilleuse, chose her dress because it looked the best on her; the king is displeased, calling her vain. Then he asks about their latest dreams. The first two dreamed he brought them gifts, but the youngest dreamed he held a basin for her to wash her hands. The king is furious at the idea he would become her servant (ATU 725, "The Dream" - like the Biblical story of Joseph). He decides to get rid of her (“Love Like Salt”, “King Lear”). He orders the captain of the guard to kill her and bring back her heart and tongue; instead, the captain warns her to flee and brings back the heart and tongue of her pet dog (“Snow White”). Bereft, Merveilleuse travels until she discovers a splendid kingdom inhabited by sheep, ruled over by a royal ram. The Ram explains that he is a human king, cursed after he refused to marry a wicked fairy (“Beauty and the Beast”). But the time limit of his curse will soon run out, so if Merveilleuse just hangs in there a little while, she’s guaranteed a handsome king husband. She also gets to ride in the Ram's pumpkin coach ("Cinderella"). Eventually they hear that Merveilleuse's sister is to be married; the Ram agrees that Merveilleuse should attend the wedding, but asks her to return afterwards. She attends the wedding in splendor, amazing the king and courtiers who don't recognize her, before returning home (shades of “Cinderella” again). Similarly, she attends her second sister's wedding. This time, the king catches her and offers her a basin of water to wash her hands; her dream has come true. Recognizing her, he repents of his wrongdoing and makes her the new queen. Meanwhile, the Ram begins to fear that Merveilleuse has left him. He runs to her father's palace, but the guards - knowing that he will take Merveilleuse away - refuse to let him in. When Merveilleuse finally steps outside, she finds him lying dead of a broken heart, and is stricken with grief and guilt. The end. (A depressing and very racist intro, in which the heroine’s slave girl and pets foolishly sacrifice themselves in an attempt to help her, sets up for the tale’s eventual tragic ending.) D'Aulnoy's story was fairly well-known and was translated into other languages for both children and adults. Some English translations go further and have Merveilleuse die at the end, too (possibly due to mistranslation - in D’Aulnoy’s version, we may assume Merveilleuse reigns on her own as queen). Others alter it to have a happy ending; Sabine Baring-Gould, for instance, introduces the plot point that the Ram must sit in a king’s throne and drink from a king's cup to break his curse, and the heroine (renamed Miranda) is able to gain this favor during her reconciliation with her father. This turns the story on its head, making the family reunion the solution to the problem rather than the issue that breaks the couple apart. There is also a Portuguese tale, “The Maiden and the Beast," which runs much more like the familiar "Beauty and the Beast." Rather than a rose, Daughter-No.-3 requests "a slice of roach off a green meadow". A roach is a fish, so she’s asking for an impossible thing, a fish from a grassy field. The Beast is only heard as a voice, never appearing in person. The biggest divergence is the ending. During her stay at the Beast’s castle, the girl returns home for three days for her oldest sister's wedding, then again for her next sister's wedding, and finally for the death of her father. She even takes rich gifts back with her, making the family wealthy. However, on the third visit, she is warned that her sisters will sabotage her. Sure enough, they sneakily let her oversleep and take her enchanted ring, causing her to forget everything. When she finally remembers, she rushes back to the enchanted palace and finds it deserted and dark. In the garden, she discovers a huge beast lying on the ground (the first time the Beast has appeared in person). He bitterly reproaches her for breaking his spell, and dies; the heartbroken girl dies a few days later, and the surviving sisters lose their money. It’s never mentioned what this Beast’s deal is, whether he’s a man under a curse or what. However, much like other versions of Beauty and the Beast, the context makes it clear that this is a fantasy version of an arranged marriage; the father knows full well that he is trading his daughter for the "slice of roach." The moral...? There's a prevailing theory that "Beauty and the Beast" is a moral lesson about accepting an arranged marriage and learning to see the good in an unfamiliar spouse. These tragic stories show what happens when the heroine accepts her new spouse but still fails to completely take on her new role as wife. She’s distracted by her family, who are unwilling to let her go. You could make a case that these stories are about the danger of female disobedience (and, for “The Ram”, something about the whims of fate). However, it doesn’t seem right to blame the heroines for disobedience. Merveilleuse and the maiden both fully intend to comply with the Beast character’s request. However, both are thwarted by their own innocent forgetfulness and by household members fighting to keep them home (the Maiden’s sisters interfering with her return, and Merveilleuse’s father locks the palace doors in order to keep her there, followed by the guards keeping the Ram out). It’s different from the older sisters’ jealous sabotage in “Cupid and Psyche” or “Beauty and the Beast.” In these tragic versions, the family members are, ultimately, acting out of misguided love - fearing the husband-monster-interloper, wanting to keep a beloved youngest child with them rather than let her become a married woman in a household of her own. Do you know any Beauty and the Beast stories that end tragically? Let me know in the comments! SOURCES

1 Comment

Petrus Gonsalvus, or Pedro Gonzalez, lived at the court of the French king Henri II. Gonsalvus had a condition which today would be diagnosed as hypertrichosis, causing excessive hair growth; his face was almost completely covered in hair. People who met him would have thought immediately of the wild men of medieval legend. Around age ten, he was brought to court as a kind of curiosity and pet, much like other people with physical differences at the time. This is where he grew up, was educated, and eventually married a woman named Catherine. Most of their children shared Gonsalvus’s diagnosis; so did some of their grandchildren. Their medical studies and portraits still survive today. But was there more than a scientific interest to Gonsalvus's story? Were he and his wife the original inspiration for "Beauty and the Beast?"

I have never seen Gonsalvus mentioned in any analysis of the fairy tale, which is well-known to be inspired by an ancient storytelling tradition. That's not a great sign. But the theory has been shared around a fair amount and has some traction, so it deserves a look. The most well-known English work about Gonsalvus is probably a Smithsonian Channel documentary titled "The Real Beauty and the Beast”, directed by Julian Pölsler (2014). As seen by the title, it strongly promoted the fairy tale connection. It is no longer available on any streaming services, but based on the various reviews and summaries I’ve found, it runs something like this. Pedro is brought to Henri II’s court as a feral child: kept in a cage, fed raw meat, and unable to say anything but his name. Henri II bestows an education on him, translating his name into Latin as Petrus. Petrus thrives in his new life, but Henri II’s wife, the villainous Catherine de' Medici, designs a sadistic experiment to see whether Petrus’s children will also be hairy. She marries him to one of her servant girls, also named Catherine. The bride knows nothing about her groom, and faints when she sees him for the first time at the altar. Their union ends up being a happy one as she discovers Petrus is a kind and gentle man. Still, their happiness is marred, as their children who inherit Petrus’s condition are taken away and gifted to various nobles, and even though Petrus and Catherine ultimately settle down to a quiet life in Italy, the lack of burial records is interpreted to mean that Petrus is still seen as a beast and denied the Christian rites of burial. It’s a tragic Beauty and the Beast retelling complete with the moral of looking beyond appearances and plenty of memorable dramatic details (like Catherine "fainting at the altar.") This documentary seems to have been heavily fictionalized, and does not seem like a reliable source. (Incidentally, Beauty faints at the first sight of the Beast in the 1946 film La Belle et la Bête, although not in the fairy tale. So I wonder if the filmmakers actually drew from Beauty and the Beast stories to craft their depiction of Petrus and Catherine. As we'll see in a minute, there's no historical basis for details like Catherine fainting.) The Gonzalez family in historical record We can only get at the Gonzalez family’s story by piecing together brief and scattered sources. It’s hard to pin down dates, and English studies are especially scarce. Gonsalvus was known in life as "le Sauvage du Roi" (“the King’s Savage”) or, more personally, “Don Pedro.” His name appears under many different translations; it seems like he preferred Pedro, so that's what I'm going with. He was born in Tenerife in 1537, spoke Spanish, and was probably Guanche (the indigenous people of Tenerife, enslaved by the Spaniards during conquest). It may be that he was brought straight from Tenerife by slave traders. On the other hand, Alberto Quartapelle found another account from about the same time of a hirsute ten-year-old shown off throughout Spain by his father; given the rarity of the condition, it’s possible that this was Pedro, and that his own father showed him off and eventually gave or sold him to the French king. What is generally agreed on is that Henry II wanted to prove that a “savage” could be transformed into a gentleman. He arranged for Pedro to live like other noble children of court and receive a royal education. He chose important officials as Pedro’s tutors and caretakers. As he grew older, Pedro served at the king’s table, a small but still prestigious task with a salary and personal access to the monarch. After Henri II's death in 1559, his widow the regent Catherine de'Medici became Pedro’s main patron. She probably did either arrange his marriage or, at the very least, promise financial support (she arranged marriages for her court dwarfs). In Paris, in 1570, Pedro married Catherine Raffelin (spelled variously as Raphelin, Rafflin, Rophelin), the daughter of Anselme Raffelin (a textile merchant) and Catherine Pecan. As part of her dowry, Catherine Raffelin brought half of an apartment on Rue Saint-Victoir, where the couple moved. We don’t know what they may have thought of each other at first or what their first meeting was like. However, Pedro’s extensive education and wealthy lifestyle would presumably have been appealing to a potential wife. Portraits of Pedro and Catherine are reminiscent of Beauty and the Beast. And not only was Catherine a merchant’s daughter just like the Beauty of the fairy tale, but it seems she was considered a lovely woman. A portrait by Joris Hoefnagel (included at the top of this post), which shows Catherine resting a hand on her husband's shoulder, was accompanied by a segment written from Pedro’s point of view (possibly even by Pedro himself?) describing Catherine as “a wife of outstanding beauty” (Wiesner 153). Merry Wiesner lists their seven children as Maddalena, Paulo, Enrico, Francesca, Antonietta (“Tognina”), Orazio, and Ercole. All three girls plus Enrico and Orazio had hypertrichosis. Ercole apparently died in infancy, with records unclear whether he was hirsute. With baptismal records, Quartapelle places their births a few years earlier than Wiesner’s estimates and gives the initial four (in French) as Francoise, Perre (Pierre?), Henri, and Charlotte. Some children were recorded more than others, which means some may have died young; alternately, the children who didn’t inherit hypertrichosis were not recorded as much. During his years in Paris, Don Pedro studied at the University of Poitiers and became a professor of canon law. He was also in frequent contact with the king, being tasked with delivering his books. Important noblemen close to the royal family served as godfathers to the Gonzalez children. However, around the 1580s or 1590s, something happened. The family began traveling and showing up in the records of various European courts. This was also the period when many of the portraits and medical studies were done. We don't know exactly when they left, but the queen's will provided for her court dwarfs and not the Gonzalezes, which might indicate that they already had a new patron by then. It's not clear exactly why this happened, but in 1589 there were a couple of significant events: the death of Catherine de'Medici and the assassination of her son Henri III (Ghadessi p. 109-110). France was full of civil and religious unrest, Henri III's death sent people into a frenzy of joy, and it was probably not the best time to be an easily-recognizable favorite of the royal family. If the Gonzalezes hadn't already left, that would have been the time to get out. They ultimately entered the patronage of Duke Alessandro Farnese and settled at his court in Parma, Italy. The children with hypertrichosis lived similarly to their father, sent as gifts to the courts of Farnese relatives and friends. Despite this disturbing note, it does seem that the family kept in contact. Most or all of them eventually moved to the small village of Capodimonte. Their sons found wives there, and Orazio occasionally commuted from there to Rome, where he held a position in the Farnese court (Wiesner, 220). Pedro is thought to have died in Capodimonte around 1618, Catherine a few years later. There’s debate over how much agency the family members had, but Roberto Zapperi argues that their son Enrico used his position wisely and pulled strings with the Farneses to make this quiet retirement possible (Stockinger, 2004). So, a couple of notes on the information floating around from the Smithsonian documentary. First, it apparently painted Catherine de’Medici as a cruel woman who treated the Gonzalez family like a science experiment. In a completely opposite take, scholar Touba Ghadessi suggests a protectiveness, honor, and perhaps even fondness in her patronage of the family. I wonder if the truth is some mixture of the two; it wasn't necessarily black and white, and there could have been both fondness and rampant exploitation. Oddly enough, Catherine de' Medici had a little bit in common with the Gonzalezes. She, too, was foreign, and her enemies described her as monstrous. And the Gonzalezes ultimately settled in her homeland of Italy. As for the burial thing: the fact that we don't have burial records for Pedro doesn't really mean anything. The records are so spotty that it's not even clear what all of his kids' names were. Furthermore, we have baptismal and burial records for some of his children who shared his condition. I don't believe he was "denied a Christian burial" or anything like that. The inherent contradiction is seen in the fact that Pedro was married. However... it’s true that in spite of gaining some privileges - pursuing his studies, finding a wife, settling down in a quiet home - Pedro was never fully free. He was taken from his childhood home and possibly even shown off around Spain by his own father. He and his children lived their lives being othered and commodified by those around them, viewed as curiosities and entertainment. And societal attitudes towards him and his family show in the family portraits, where Gonsalvus and his children wear courtly dress but are juxtaposed against caves and wild scenes befitting animals. The fairy tale of "Beauty and the Beast" The story that we know today as “Beauty and the Beast” is not a folktale, but a literary fairy tale, originating with Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve’s Beauty and the Beast (1740). This was a fantasy novella following conventions of the time, full of vivid descriptions and convoluted subplots. It took clear inspiration from folktales of beastly bridegrooms. The earliest written examples of this tradition are “Cupid and Psyche” (Rome, 2nd century AD) and “The Enchanted Brahman's Son” (India, ~3rd-5th centuries AD). People in Pedro and Catherine's time might have read Straparola's "The Pig King" from the 1550s. Closer to home for Barbot, there was D'Aulnoy's "The Ram" (1697) and Bignon's "Princess Zeineb and the Leopard" (1712-1714). Because "Beauty and the Beast" is literary, created by a single author, it’s far more likely to contain specific references or traceable inspirations than an oral folktale would be. So, was Pedro Gonzalez one of Barbot's influences? Well… it's not clear if Barbot would have known who Gonzalez was. The family's personal history has only regained attention since the 20th century, with researchers like Italian historian Roberto Zapperi doing a lot of the work to piece together the details. The family’s legacy seems more associated with Austria than with France. Their portraits in Ambras Castle in modern-day Austria remained famous, even leading to the name "Ambras Syndrome" for a type of hypertrichosis. But an inventory of the Ambras Castle collection listed Gonzalez as “der rauch man zu Munichen”, or “the hirsute man from Munich,” because that’s where the portraits were painted (Hertel, 4). Meanwhile, in France: in 1569, author Marin Liberge could make reference to “the King’s Savage” expecting that his audience would know who he meant (Amples discours de ce qui c'est faict et passe au siege de Poictiers). But by the late 19th century, French researchers were absolutely baffled by this cryptic description, not connecting it to the portraits at all. One researcher in 1895 was on the right track with the idea that Don Pedro was some type of entertainer, but also noted that his memory simply isn’t well preserved in historical records, and questioned how well-known he actually was (Babinet 143-145). When Barbot was writing in 1740, a hundred and fifty years after Gonzalez's heyday in Paris, how well was he remembered? Did Barbot ever hear of the Ambras Castle collection? Even if she did, how much would she learn of Catherine - who was only in the portraits as Gonzalez's anonymous wife? In fact, Barbot’s novel features several vivid descriptions of the Beast, and he doesn't look anything like Pedro Gonzalez. He is covered in scales, with an elephant-like trunk. This Beast seems more influenced by stories of snake husbands - like the two oldest recorded versions of beastly bridegroom tales. Psyche fears that her husband is a serpent or dragon (although Cupid never actually appears this way in the story), and the Enchanted Brahman’s Son is a snake. With the lack of parallels and number of differences, it seems unlikely that Gonzalez inspired this. A few years later, Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont wrote a shorter, child-friendly adaptation of “Beauty and the Beast” which became pretty much the canon version. In her version, the Beast is barely described. This gave illustrators the freedom to imagine their own interpretations. You’ll find images of the Beast as an elephant, bear, wild boar, lion, or walrus. Depictions leaned more towards large, hairy beasts associated with strength and fearsomeness. In the era of adaptation and illustration, the Beast is more likely to be some kind of bipedal chimera. This leads up to the most iconic film portrayal: Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film La Belle et la Bête with its leonine Beast. The resemblance between the Gonzalez portraits and Cocteau’s Beast in his extravagant ruff and doublet is so striking that it seems likely the makeup artist, Hagop Arakelian, drew inspiration from Pedro Gonzalez (Hamburger, pp. 60-61). Similarly, Disney artist Don Hahn recalled the Gonzalez portraits as "one of many sources of inspiration" during early design stages for the 1991 animated film Beauty and the Beast (Burchard, 173). So, did the author of Beauty and the Beast take inspiration from Pedro Gonzalez and his wife Catherine? Probably not; there's nothing to indicate that she did, and a few things to point against it. But did later artists? Possibly! Fairy tales are archetypal, resonating with universal morals and fears. Trying to attribute a fairy tale to a real person's biography is dangerous ground. But sometimes real people do get adopted into storytelling tradition, and what's more, real events can have parallels to fairy tales. Sometimes, there really is a hairy nobleman who marries a merchant's beautiful daughter. We know very little about Pedro and Catherine Gonzalez; we don't know whether they had a romance for the ages. But their story is worth remembering, and I hope scholars are able to uncover more about them. SOURCES

Further Reading The opening of the Italian fairytale "Prezzemolina" is near-identical to Rapunzel, but then the story takes a totally different direction. It becomes something like a gender-flipped versions of stories like "Master Maid" or "Petrosinella," where the hero is in danger from a villain, but is rescued by the villain's beautiful and magical daughter. In this version, it's a heroine who's rescued by the wicked witch's handsome son. There are two primary versions of the tale, so I'll list them in the order of publication.

Imbriani's Prezzemolina The story of "La Prezzemolina" begins just like Rapunzel and the older Italian "Petrosinella," with a pregnant woman craving parsley. Some fairies live next door, so she climbs into their walled garden to steal their parsley. They eventually catch her, and tell her that they will one day take away her child. The woman has her baby, who is named Prezzemolina (Little Parsley). The fairies collect her when she reaches school-age, and she grows up as their servant. They give her impossible tasks and threaten to eat her if she fails. Fortunately Memé, the fairies' cousin, arrives and offers to help in exchange for a kiss. She sharply refuses the kiss, but he helps anyway with a magic wand and mysterious powers. She goes through several tasks, including going to Fata Morgana (Morgan le Fay) to collect the "Handsome Minstrel's" or "Handsome Clown's" box, only to open the box and lose the contents. But Memé is always there to assist, and in the end they destroy all of the fairies and get married. The tale appeared in Vittorio Imbriani's La Novellaja fiorentina (1871, p. 121). Italo Calvino, who adapted it in his Italian Folktales (1956), called it "one of the best-known folktales, found throughout Italy." He noted the presence of "that cheerful figure of Memé, cousin of the fairies." This could imply that Memé is a popular folk figure. Imbriani, the original collector, suggested that Memé is Demogorgon, the terrifying lord of the fairies in the 15th-century poem Orlando Innamorato. The name Demogorgon probably came from a misreading of the word “demiurge” in a 4th-century text, and developed to mean either an ancient supreme god or a demon. The biggest similarity I can see is that Fata Morgana plays a villainous role in both “Prezzemolina” and Orlando Innamorato. I’m not sure of Imbriani’s thought process, other than the fact that Orlando vividly describes Demogorgon punishing the fairies. Imbriani also compared Memé to the fairy cat Mammone, who hands out magical rewards and punishments in the fairytale “La Bella Caterina.” Again, I’m not clear on why, except that Memé sounds kind of like Mammone. I may be missing Italian context. In both cases, Imbriani implies that Memé holds some kind of power or authority over the fairies. This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me; Memé seems to be on the same level as the fairies, and is apparently the black sheep of the family. The fairies seem automatically suspicious that he might help a human girl. When they see Prezzemolina’s first impossible task completed, they immediately guess (as Calvino puts it), “our cousin Memé came by, didn't he?" They later tell Meme their plans to kill Prezzemolina, perhaps in an attempt to goad him. Visentini's Prezzemolina Another version, also titled "Prezzemolina," appeared in Canti e racconti del popolo italiano by Isaia Visentini (1879). This version begins with seven-year-old Prezzemolina eating parsley from a garden on her way to school and being kidnapped by the angry witch gardener. Here, the handsome rescuer who only wants a kiss is Bensiabel, the witch's son. This version features different tasks, but one quest still involves retrieving a casket, and in the end Bensiabel kills the witch and Prezzemolina finally agrees to marry him. Andrew Lang published a translation in The Grey Fairy Book (1900), but changed the plant and the name. The vegetable garden became an orchard, the parsley became a plum, and the heroine's name became Prunella. This resembles early translations of Rapunzel where English writers struggled to render the name and came up with "Violet" or "Letitia." However, in this case the reason may be that Lang had already published The Green Fairy Book (1892) with the German tale "Puddocky," which had a near-identical opening with a heroine named Parsley. Lang did not mention a source, but "Prunella" is clearly drawn from Visentini's story. Bensiabel's name may come from the Italian "ben" (well) and "bel" (nice). This seems supported by the French translation, Belèbon, in Edouard Laboulaye's 1881 retelling "Fragolette." Belèbon may be from the French "bel" (attractive) and "bon" (good). Like Lang, Laboulaye turned the parsley into a fruit, in this case strawberries (Italian fragola). Cupid and Psyche As Calvino implies, there are a number of similar tales. Charlotte-Rose de la Force - the author who gave us the modern Rapunzel - also wrote a story in 1698 called "Fairer-than-a-Fairy" which followed some of the same motifs as Prezzemolina. The heroine, Fairer-than-a-fairy, is kidnapped by Nabote, Queen of the Fairies. Nabote's son Phratis falls for Fairer and helps her. Calvino published another tale with similar plot beats, titled "The Little Girl Sold with the Pears" (p. 35), noting that he made numerous edits. The original, "Margheritina," collected by Domenico Comparetti, is even closer to Prezzemolina, with the heroine's unnamed prince being the one to magically aid her. Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 425, The Search for the Lost Husband, is a large family of tales with many subtypes. 425C is Beauty and the Beast. In the current breakdown, 425B is "The Son of the Witch." When Hans-Jorg Uther codified this, he wrote "The essential feature of this type is the quest for the casket, which entails the visit to the second witch’s house. Usually the supernatural bridegroom is the witch’s son, and he helps his wife perform the tasks." In the Pentamerone (1634-1636) is a story titled "Lo Turzo d'Oro" - literally "The Trunk of Gold," but also titled "The Golden Root" in translation. When the heroine Parmetella is completing her tasks to win back her husband Thunder-and-Lightning (Truone-e-llampe), he helps her through each task. This is the bloodiest variant I've read. Laura Gonzenbach's story "King Cardiddu" also features a male character who's imprisoned by the villain but manages to provide magical help to the heroine. Giuseppe Pitre collected a Sicilian tale called "Marvizia" (Fiabe, novelle e racconti popolari siciliani, 1875). The heroine is named for her resemblance to a "marva" or mallow plant. The villain is an ogress named Mamma-Draga. It's a long and elaborate tale, but in a section similar to Prezzemolina's quests, Marvizia is assisted in her tasks by a giant named Ali who works for Mamma-Draga. However, he's not the love interest; Marvizia marries a captured prince whom the villainess turned into a bird. (This story features an ogress who eats people "like biscotti," and the hero wishes for a literal bomb with which to blow up her castle. I just felt that was important to note.) "Cupid and Psyche," recorded in the second century, is the uber-example. Psyche loses her divine husband Cupid and must complete her goddess-mother-in-law Venus's tasks to get him back. Although the tasks are meant to be impossible, Psyche completes each one with help from nearby creatures. Finally she must go to the Underworld and retrieve a box from Persephone, but foolishly opening it, falls into a deep sleep. At this final point, Cupid steps in and rescues her. Prezzemolina and similar tales are neighbors of the "Cupid and Psyche" tale - related to stories like "East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon." They don't have the beastly transformation, or the scene where the love interest is about to be forced to marry the wrong girl. However, they share the motif of the girl faced with impossible tasks including retrieving a magical box, and being aided by her supernatural lover. Taken to its furthest conclusion, this casts interesting parallels from Prezzemolina to Beauty and the Beast tales. Beauty's father is forced to hand his daughter over because he stole a flower from the Beast's garden - a very Rapunzel moment. Prezzemolina's suitor constantly begs for a kiss, the Beast asks Beauty to marry him, and the Frog Prince requests to sleep on his princess's pillow. Memé and Bensiabel would then be related to Cupid and the family of beastly bridegrooms. Echoing Cupid, they're benevolent sorcerers or minor deities smitten with a mortal girl, who defy their divine or monstrous mothers to help. Unlike the lost husband figure, the Memé figure is never under a curse, and is right there alongside the heroine for the whole tale. She has no need to pursue him, because he's wooing her the entire time. With its unique mix of fairytale tropes, I'm not sure whether the Prezzemolina type would be best categorized as 425B, "The Son of the Witch," as 310, "The Maiden in the Tower," or as something else entirely. Other Blog Posts The story of "Prince Lindworm" or "Kong Lindorm" is ATU 433B, related to the Animal Bridegroom tale family. Many variants of the Animal Bridegroom story feature serpents, but this one is rather unique. And upon researching it, I soon learned that pretty much everything I knew about this story was wrong.

A lindworm is a dragon usually shown with just two legs, often seen on coats of arms. Although the stories are very different, "Prince Lindworm" begins with a scene almost identical to the start of "Tatterhood." In both, a queen who wants a child encounters an old woman who gives her instructions on getting one. Tatterhood's mother pours water beneath her bed, and the next morning finds a lovely flower and an ugly flower there. Lindworm's mother places a cup upside-down in her garden, and the next morning finds a white rose and a red rose underneath. In both cases, there's a warning. Tatterhood's mother is instructed not to eat the ugly flower, while Lindworm's mother is told to pick only one (red for a boy, white for a girl). But both are overcome by temptation, because the first flower "tasted so sweet" - the same reason in both versions. This hunger and greed symbolizes sexual temptation. It also hearkens to myths that blamed women for birth defects - like "maternal impression," the idea that the mother's thoughts or surroundings could influence her unborn child. For Tatterhood, a connection seems clear: Tatterhood's pretty twin is created by the beautiful flower, and the outwardly repellent Tatterhood by the foul-looking plant. The twins are fundamentally opposite, yet love each other deeply. The same motif drives "Biancabella and the Snake," an Italian tale by Giovanni Francesco Straparola, where a woman gives birth to a baby girl with a snake around her neck. The snake, Samaritana, serves as a supernatural helper to her human sister, Biancabella. She eventually doffs her serpent skin and becomes a woman without explanation. (Italo Calvino collected a folktale, "The Snake," with the same story - except that the snake is merely a helpful animal, not an enchanted sibling.) In the opposite of these tales with diametrically opposed siblings, there are stories where two women eat of the same food and bear identical children. You find this in the Italian "Pome and Peel" and the Russian tale of "Storm-Bogatyr, Ivan the Cow's Son." In "Ivan the Cow's Son," rather than a woman giving birth to an animal, a cow gives birth to a human. But Prince Lindworm apparently follows a different internal logic. The queen is hoping to have both a son and a daughter when she eats both roses; this makes sense, even though it's incredibly stupid to disobey instructions in a fairytale. In fact, she eats the white rose first, so you would think she would have a daughter first. However, what she gets is a male lindworm and a baby boy - twins, as in "Tatterhood" or "Biancabella," one perfect, the other monstrous. The lindworm baby escapes and is not seen again until, years later, the second prince prepares to marry. The lindworm returns; as he is firstborn, he says he should get married first. The royal family obtains a bride for him, but the lindworm eats her on their wedding night. Before you know it, we're on Bride #3, and she quickly deduces that this isn't going to end well for her. However, an old woman gives her advice. Bride #3 is savvier than the queen and follows the instructions exactly. On her wedding night she wears ten white shifts and tells the lindworm to shed one skin every time she takes off a layer of clothing. Once he's removed nine skins, there's nothing left of him but a mass of bloody flesh. She beats him with whips dipped in lye, then bathes him in milk, and finally takes him in her arms. When people come to check on them the next morning, they find her sleeping beside a handsome human prince. Marie-Luise von Franz interpreted the lindworm as a "hermaphrodite": “a masculine being . . . wrapped up in the feminine or the dragon skin. . . . Prince Lindworm is also a man surrounded by the woman, but he is in the form of a lump of bleeding flesh surrounded by a dragon skin, a regressive form of the union of the opposites.” In alchemy, according to von Franz, hermaphrodites are closely connected to dragons and serpents. This explanation fails for me. The white rose was eaten first. Surely the feminine element should be at the center of the lindworm's being? What makes scales feminine and blood masculine? The biggest stumbling block is the existence of the twin brother. Why wasn't he affected? Going by the opening scene, it seems to me, the lindworm should either be a princess or have an older sister. Taking a step back: the motif of the enchanted prince removing his animal skin is familiar. In "Hans My Hedgehog," a couple wishes desperately for a child, but their son is born as (wait for it) a hedgehog. He tries several times to take a bride, but the first girl is unwilling and he stabs her with his prickles. The second is willing, and on their wedding night he removes his hedgehog skin to become a handsome man. The same thing happens in the Italian "The Pig King." Both stories are Aarne Thompson type 441, the hog bridegroom. Very often this tale includes a number of false starts to marriage, where the enchanted bridegroom turns horrifyingly violent towards the maidens who reject him. The removable skin seems more appropriate for serpents, which really do shed their skin, and which in many cultures are symbols of rebirth and transformation. And there is a widespread tale type of snake and serpent husbands, type 433C. Prince Lindworm is unusual in that he must remove multiple skins. His transformation is more involved than these other examples. He must also be whipped and bathed. The act of bathing suggests baptism, and thus forgiveness of sins and rebirth. (And he needs that forgiveness of sins after all that snacking on maidens.) It's a little more odd that he is bathed in milk. However, there's a widespread tradition of offering milk to snakes. In Hinduism, milk is offered to snake idols, for instance on the feast of Nag Panchmi. So you get Indian folktales like "The Snake Prince," where in order to restore her husband from his serpent form, the heroine must put out bowls of milk and sugar to attract all the snakes and gain an audience with their queen. According to Arthur Evans, a similar tradition of milk offerings for "household snakes" existed in Greece, Dalmatia and Germany. Marija Gimbutas said that this practice persisted in Lithuania up into the 20th century. Snakes actually can't digest dairy products and do not drink milk unless suffering from dehydration. In the Turkish tale of "The Stepdaughter and the Black Serpent," the heroine serves as a nursemaid for the serpent prince. When he's an infant, she keeps him contained in a box of milk. When he leaves the box, she beats him with rose and holly branches to deter him from hurting her. He eventually wants to take a wife, but kills forty (!) brides one after another. The heroine, chosen as his bride, wears forty hedgehog skins and asks the snake to remove one skin every time she does. After removing forty snake skins, he is left as a human and they burn the snake skins.It's the same tale as Prince Lindworm, except that the order of events is different. There's also no twin brother to complicate things. "The Stepdaughter and the Black Serpent" was recorded long after Prince Lindworm, but what if it's closer to the original form of the story? I began to wonder if the opening scene and the twin brother were foreign to the essential tale. They certainly do not appear in most variants of the tale type. The Animal Bridegroom, which often begins with the desire for a child, could easily have been combined with similar stories like Tatterhood or Biancabella. The twin brother/missing sister problem would then exist because that element was added later. Soon after, I learned Prince Lindworm's true origins. Most modern sources call it Norwegian, but it's actually Danish. It was collected in 1854, and the original version is very different. D. L. Ashliman did an English translation. In the oldest version of "Kong Lindorm," the queen eats both roses, but has only one child - the lindworm. There is no twin brother. Marie-Luise von Franz's premise finally begins to make sense! The story otherwise proceeds roughly as I knew it, but there is a second half that was completely new to me. Now happily married to the former lindworm, the heroine gives birth to twin boys, but an enemy at court gets her exiled. She uses her own breast milk to disenchant two more cursed men (King Swan and King Crane), before her husband finds out what happened and retrieves her. "Kong Lindorm" was first published by Svend Grundtvig in Gamle danske Minder i Folkemunde (1854). A Swedish version, "Prins Lindorm," was published in 1880. This was a very close retelling of the first version, with one important difference: the opening. This time, the queen is given instructions for bearing twins, no mention of whether they will be male or female. She is supposed to carefully peel the two red onions she grows, but she forgets to peel the first one. Storytellers might have added the twin brother because they confused this story with Tatterhood, which - as previously mentioned - has a strikingly similar beginning. Then a variant appeared in Axel Olrik's Danske Sagn og Æventyr fra Folkemunde (1913). This was almost identical to the first Kong Lindorm, except that it included the twin brother. However, the storyteller did not otherwise alter the opening, so the birth of twins made no sense. The second half was hacked off, perhaps because the writer didn't want to talk about breast milk, and also because that's where the story starts to drag. This short version was translated into English in 1922, in a book titled East of the Sun and West of the Moon: Old Tales from the North. There, it was thrown in alongside Norwegian stories collected by the famous Asbjornsen and Moe, leading to the confusion around its origins. So there you have it. The version I knew had been simplified and altered. Ultimately, the story's sense of confusion stems from careless editing and a misunderstanding of the tale's logic. Adding in a second child obscures the idea of the older tale. In fact, the white rose leads to a daughter, a red rose leads to a son, and both roses together make a giant dragon monster. Simple, right? Okay, I think it's really about 19th-century sexual mores for women. The queen's intemperance leads to a curse which affects her unborn child and generations to come. She hungered for extra roses (read: she was lustful), so her child is neither man nor woman and can't have a normal marriage. Echoing his mother's method of conception by eating, the only way he can engage with a woman is by devouring her. And his wives die because they are not behaving correctly on the wedding night. When Bride #3 follows proper instructions, she redeems her husband and can look forward to a happy and fruitful marriage. Note that she is still wearing one shift by the end of the cursebreaking ritual, indicating modesty and chastity. This is different from the Indian version, where the girl and the serpent shed the same number of skins. There's also an Oedipal note to it; she must bathe him in milk in order for him to be reborn. That original maternal sin has to be corrected. The longer version even doubles down on the milk motif. You can read a translation of the original version here, and the popular English version here. Further Reading

"Nya-Nya Bulembu or the Moss-Green Princess" is a tale from Swaziland. I first found this story summarized in the picture book Finding Fairies: Secrets for Attracting Little People From Around the World. The story was intriguing, and I tracked down the original version in the 1908 book Fairy Tales from South Africa.

In the 1908 version, there is a Chief with two wives and a daughter by each one. He loves one daughter, Mapindane, and despises the other, Kitila. Wanting to humiliate Kitila, the chief has his hunters go out seeking a monster called the Nya-nya Bulembu, a hideous beast with a moss green hide. He sends his huntsmen to find such a creature. They find one living in a blue pool, but when they summon it with a chant, it turns out to be old and toothless with no moss on its hide. The second is equally unimpressive. Finally, they find a suitably terrifying beast in a green pool. They bring it home and skin it. When Kitila is wrapped in the skin, she cannot remove it and becomes indistinguishable from a normal Bulembu. She is left to live as a servant, abhorred by everyone for her monstrous appearance. However, one day she meets a fairy man who takes pity on her and gives her a carved stick. From then on, whenever she goes to bathe in the river, she is joined by the fairies, her monstrous skin comes off, and she becomes beautiful again for a little while. One day, a visiting prince sees her bathing and is stricken by her beauty. Even though she becomes hideous again when she leaves the water, he takes her as his wife. When she goes to bathe on the morning of their wedding, her Bulembu skin is finally stripped off once and for all. The couple lives happily ever after. The book is verrry dated. Although the foreword says that the tales are traditional, I was unsure whether I would find other versions of it. It turns out that Nyanyabulembu (plural dinyanyabulembu) is a Setswana word which translates as dragon. I also found the story "A Boy Goes After a Nyanyabulembu," performed by Sarah Dlamini, in the book The Uncoiling Python: South African Storyteller and Resistance. In this story, a king wants a Nyanyabulembu skin to make a coat for his child - not as a curse, but as a sign that this child is beloved and will one day be the next king. Only one boy is brave enough to go hunting the monster. Just like the huntsmen in the first story, he visits two blue pools, where he summons the monster with a short chant, but finds it unimpressive. At a third, green pool, he finds a strong, healthy monster. It chases him, and at the end of the chase the monster is killed, the boy is greatly rewarded, and the monster's skin is turned into a ceremonial cloak for the next king. In some places, there are parallels - most notably, the repetition of finding the monster in its pool and trying to find one suitably frightening. However, the intent of the hunt and the creation of the Nyanyabulembu cloak is completely different. One story is reminiscent of Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast. The other is the tale of a young man coming of age. EDIT 7/2/2018: I've found another version of the story! "The Ogre Scaly-Heart" (Nwambilutimhokora) features a beautiful young bride who, en route to her wedding, is forced to switch places with an ogre and wear a hideous monster skin. When she's alone, she takes off the skin and bathes in the river, and is joined by the ghosts of her relatives and servants. The truth is revealed when a child sees her and tells the intended husband. (The life of a South African tribe, vol 2, by Henri A. Junod.) And even more variants exist:

Sources

The Search for the Lost Husband is a very widespread tale, closely related to Beauty and the Beast. Sometimes it seems like it's a default ending for fairy tales.

A woman marries a supernatural male being, who seems monstrous at first and might be enchanted in animal form, only appearing human at night. The wife breaks a taboo, and her husband vanishes. She then searches the world until she finds him and they are reunited. A non-exhaustive list of stories falling into this category:

The hero is a woman, and her opponent is usually a woman - an enchantress who's trapped the husband, or a rival princess who wishes to wed him. In their notes, the Grimms wax a little poetical on how the story is about the heart being tried so that "everything earthly and evil falls away in recognition of pure love." There's also an interesting note about, in this case, light being an ill omen and darkness being good. This goes back to the taboo. Often, she takes a candle and spies on her husband in the night to see his human form, or attempts to break his curse by burning his animal skin. Karen Bamford has a good analysis. The wife's journey is an act of atonement; she does penance for sinning against her divine husband, and wins him back through toil and effort. In many cases, her long journey takes her through some kind of otherworld. In an Arabic version, "The Camel Husband," the heroine goes to the land of the djinn. The land East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon is a place beyond the bounds of the physical world and the laws of nature. Psyche literally goes through hell. This quest allows her to finally truly break the spell on her husband and resurrect him from a "metaphoric death" (Bamford). In many tales, the wife visits the husband during the night, while he lies in a drugged sleep, and tries repeatedly to awaken him. In "Nix Nought Nothing," the husband falls into sleep similar to Sleeping Beauty, and only the true bride can symbolically raise him from the dead with the power of love. In Cupid and Psyche, Cupid lies wounded for quite some time. I found a Japanese folklore site that had an interesting perspective. (As seen through Google Translate, but whatever.) The groom's animal shape is the body, and his human shape represents the soul, but the soul belongs to the otherworld. Death and rebirth are required to truly bring it into the real world. So then you have stories like the "Frog King" or "The White Bride and the Black One" where the enchanted animal must be thrown against a wall or have its head cut off. There are stories where a husband seeks a lost wife; this is its own tale type, AT 420, The Quest for the Lost Bride. A couple of examples are the Russian Frog Princess, and the story of the Swan Maidens. In Household Tales, the Grimms mention "a man in a Hungarian story, whose wife has been stolen from him, seeks [help], first from the sea-king, then from the moon-king, and finally from the star-king (Molbech's Udvalgte Eventyr, No. 14)." Incidentally, Joseph Jacobs' version of the Swan Maidens also features the Land East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon, but that's from Europa's Fairy Book, in which he mashed up a lot of different traditions. Sources

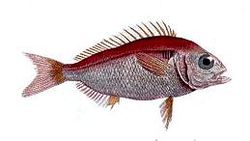

Tales of Faerie had a post a while ago on Beauty's request for a rose in Beauty and the Beast. The unique request differentiates Beauty from her materialistic and greedy sisters, who ask for clothes, shoes, or other expensive ornaments. Some themes emerge when you look at different tales, and they might not be the themes you expect. In most, she asks for a rose or other flower. Other objects close to nature might be a lily, a grape, or a green nut-twig. In "The Sprig of Rosemary," the heroine picks the titular sprig herself while gathering firewood. This is a simple request in contrast to her sisters' pleas for material goods. Unless she asks for it in winter. Then it's a fantastical request that should be impossible to grant. So her request is not necessarily simple, but impossible. The rose is the most common theme that I've found, but there are other versions that make this even clearer. A singing, springing lark. Maria Tatar says the rose and the lark, like the rose, is emblematic of the girl's character. The rose symbolizes her inner beauty and the lark symbolizes her energy and liveliness. A clinking, clanking lowesleaf. This is definitely a leaf; it's just the lowe part that's confusing. There is an impossibility implied, with a simple piece of plant matter clinking and clanking like a piece of metal. Lowe might mean lion, but that's a guess. Similarly, the German for dandelion is Loewenzahn. A pennyworth of “sorrow and love” in one English tale. Here she's asking for abstract concepts. A slice of roach off a green meadow, from one Portuguese tale. This one baffled me for a long time, but turns out, it's a FISH! There's a kind of fish called a roach. (Goraz is the word in the original Portuguese.) She is asking for a fish native to a green, grassy field - something that can't possibly exist.

Further Reading |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed