|

A while back, I set out to investigate pillywiggins - an obscure type of fairy that was oddly lacking in source material. After months of searching through bibliographies and ordering books through Interlibrary Loan, I gave up. I was at a dead end. I published my blog post and let it be.

Now I'm coming back to pillywiggins again. Bunny wrote in to say: “My late grandmother, originally from Wimborne, Dorset, would bemoan those pesky Pillywiggins whenever something went missing or awry.” (Thanks, Bunny!) Another thing I found, but that I didn't fully break down in the original post, was a My Little Pony comic. Evidently, the UK comic took "story requests;" the story "Pinwheel and the Pillywiggins," published May 1986, was requested for Wayne and Claire Cookson of Hanham, Bristol. The pillywiggins are never explained. They appear as small women with flowers on their heads (and no wings). That lack of explanation indicates that the author expected people to already understand what these creatures were. At the very least, Wayne and Claire knew what they were. This is also one of the earliest sources I have for pillywiggins, which makes it a vital piece of evidence. More recently, I bought a copy of Dark Dorset Fairies by Robert J. Newland (2006). Newland describes pillywiggins as small flower fairies with golden hair and blue wings. Despite their pretty appearance, they can be mischievous and untrustworthy. (There's no resemblance here to Dubois' insect fairies or McCoy's Queen Ariel! But it does tie in with pillywiggins being pesky troublemakers...) In one tale, a woman finds a group of tiny pillywiggins dancing upon her newly baked cake. When she tries to speak to them, they disappear into mist. (Compare Keightley, The Fairy Mythology, p.305: "as for the adjoining Somerset, all we have to say is, that a good woman from that county, with whom we were acquainted, used, when making a cake, always to draw a cross upon it. This, she said, was in order to prevent the Vairies [Fairies] from dancing on it. . . . if a new-made cake be not duly crossed, they imprint on it in their capers the marks of their heels.") In another tale, the "vearies in the honeyzuck" (vearies being a Dorset term for fairies) give gold to a pair of children, but the gold disappears as soon as the children tell how they got it. In the third story, we learn that Pillywiggins love hawthorn trees and will protect them by pinching encroachers or tangling their hair into fairy-locks. Two girls who fall asleep under a hawthorn tree wake up to find that the fairies have knotted their hair so badly that it must be cut off. The concept of fairy-locks or elflocks goes back at least to the 1590s with Romeo and Juliet. Hawthorn trees are often liminal places where humans and faeries can interact, as in the tale of Thomas the Rhymer. Newland's story takes place at May Day, a time during which the hawthorn would be blooming. In a final note, pillywiggins like to ring bluebells, and the chime of a bluebell - or fairy's death bells - is an omen of doom. In other recorded folklore, bluebells or harebells (which were often confused) were also known as witch's bells, Devil's bells, dead men's bells, or fairies' thimbles. (See this blog post at Hypnogoria.) As for an analysis of these stories: Many of the elements here, such as the fairy gold, are familiar. The cake story is one I recognize from an older source. However, I've never seen them associated with pillywiggins before. Newland's pillywiggins love honeysuckle, hawthorn, and bluebells. Each of these plants appeared in the Folklore Society's "Survey of Unlucky Plants," and were said to bring ill fortune if taken inside a house. In addition, hawthorn and bluebells have well-known connections in folklore to fairies. The word pillywiggin is mainly used in narration. At one point when it would be natural for a character to say the word "pillywiggin," she instead says "vearies." The impression I got was that the word pillywiggin was being applied to various stories of tiny plant-loving fairies, and may not originally have been associated with these tales. Some of the stories throw in names, locations, or ballpark dates, but there are no sources. There's nothing to indicate who told the story, or where or when it was told. The blue wings are a modern touch. Ancient fairies are not winged. I want to note that pillywiggin does hearken back to other words, such as pigwiggen or pigwidgeon for a tiny being. There is also piggy-whidden, a runt piglet. (Specimens of Cornish Provincial Dialect). Pirlie-winkie and peerie-winkie are words for the little finger, and peerie-weerie-winkie for something excessively small. (Transactions of the Philological Society) I'm still looking for more information, so if you've heard something about pillywiggins that I haven't mentioned, let me know! Part 1: What are Pillywiggins? Part 3: Pillywiggins in Pop Culture Part 4: Pillywiggins, Etymology, and... Knitting? Part 5: Diamonds and Opals: Two Romances Featuring Pillywiggins Part 6: Pillywiggins: An Amended Theory

0 Comments

I've been thinking about how in several different tales, a Thumbling figure becomes a favored servant of a king.

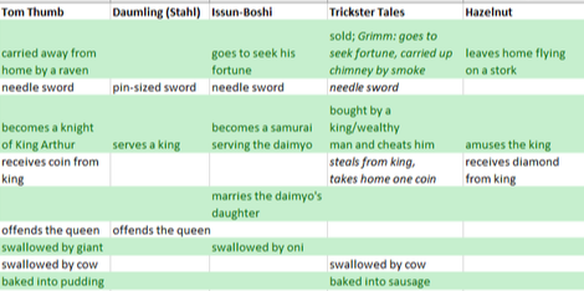

Tom Thumb becomes King Arthur's dwarf and one of his favored knights. (In later versions, he runs afoul of the queen.) Issun-boshi acts as a samurai for a daimyo, or feudal lord. The Hazel-nut Child, in a tale from the Armenian people of Romania, Transylvania and the Ukraine, makes his way to the palace of an African king. Like Tom Thumb carrying home a coin for his parents, the Hazel-nut Child brings home a diamond given to him by the king. Karoline Stahl (the same woman who wrote the first version of Snow White and Rose Red) wrote a story called Däumling. Daumling goes to live in the palace, where he serves the king and several times defends him from assassination attempts. The story was probably inspired by the British Tom Thumb. Both stories have an emphasis on the main character's clothing and needle- or pin-sized sword, as well as an evil queen. Sometimes the thumbling's encounter with the king isn't quite so pleasant. In numerous tales, the thumbling is out in the field with his father, when a rich man, sometimes a noble or king, sees him and asks to buy him. The thumbling sells himself and then runs away, cheating the rich man. In one version, Neghinitsa, the main character does not run away, but ends up working as a king's royal spy until his death. In other stories, like the German "Thumbling as Journeyman," or the Augur folktale "The Ear-like Boy," the Thumbling becomes a robber and a king is one of his victims. In a tale from Nepal (printed in German), the thumbling steals items from the king's palace and eventually wins the hand of one of the princesses. Also in "Thumbling as Journeyman," the little thief takes a single kreuzer, stolen from the king's treasury, to give to his parents back home. Here again is the same motif as Tom Thumb, where the tiny knight asks King Arthur for permission to take one small coin to his parents. In other stories, Thumbling marries the king's daughter - a common ending for fairytales. Issun-boshi marries the daimyo's daughter. In the Philippines, Little Shell and similar characters pursue the daughter of a chief. (See blog post.) In India, Der Angule completes many tasks for a king and finally marries the princess. Some retellings of Tom Thumb, such as Henry Fielding's play, have him woo a princess. I worked a little bit on a chart comparing some of these stories. I included the Grimms' Thumbling among "trickster tales." EDIT: Now with new and improved chart! |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed