|

One thing I didn't realize until I started researching folklore in depth is how much drama there is behind the scenes. For instance, take the story of "The Soul Cages."

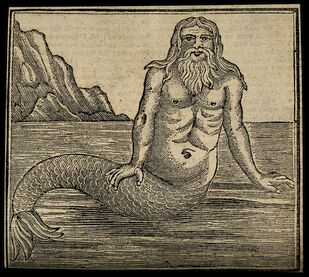

The whole thing started when Thomas Crofton Croker began his collection Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland. However, as the story goes, he lost his manuscript right before publication. A number of his Irish friends generously lent their help, writing out material and adding the folktales they knew. The result was a collaborative effort between many authors. Croker chose to publish the book anonymously, as the work of many, and it hit shelves in 1825. It was instantly popular. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm translated it into German as Irische Elfenmarchen in 1826. Croker claimed all credit. Then he got right to work on producing more material. Around 1827, he published Volume 2, but this one was under his name alone. One of the tales in Volume 2 was "The Soul Cages." Here, a fisherman befriends a merrow (merman) named Coomara (sea-hound). Coomara lends him a hat that will let him breathe underwater and invites him to visit his home on the seafloor. They have a nice meal and chat, but as the merrow shows him around, the fisherman notices a strange collection of lobster traps. Coomara explains that they are "soul-cages," containing the spirits of drowned sailors which he traps. The merrow makes out that he's doing the souls a favor by keeping them safe with him, but the Catholic fisherman is horrified. He contrives to get the merrow drunk, and then opens each of the cages to release the souls inside. From then on, the fisherman regularly pulls this trick to release souls as the merrow catches them. Croker noted the story's striking resemblance to the German "Der Wassermann und der Bauer," or "The Waterman and the Peasant," which had appeared in the Brothers Grimm's Deutsche Sagen (1816-1818). In fact, when placed side by side, the stories shared identical plots. "The Soul Cages" is simply a more elaborate retelling of the Grimms' tale with Irish names and stereotypes stapled on. There arose another issue. It seems there was controversy over Croker's manner of attributing sources - or rather, not attributing them. As one example, contemporary poet A. A. Watts wrote in Literary souvenir (1832): ...See Crofton Croker, That dull, inveterate, would-be joker, I wish he'd take a friendly hint, And when he next appears in print, Would tell us how he came to claim, And to book prefix his name – Those Fairy legends terse and smart, Of which he penned so small a part, Wherefore he owned them all himself, And gave his friends nor fame, nor pelf. One of Croker's helpers was the Irish writer Thomas Keightley. He went on to publish his own work, including the highly ambitious collection The Fairy Mythology in 1828. And he was steamed about not being credited properly in Fairy Legends. He said several times that credit wasn't important to him, but he still displayed a strong feeling that he had been used and cheated. In his 1834 work Tales and Popular Fictions, Keightley declared that he was the uncredited source for a large number of tales in the first and second volumes of Fairy Legends. He laid claim to "The Young Piper," "Seeing is Believing," "Field of Boliauns," "Harvest Dinner," "Scath-a-Legaune," "Barry of Cairn Thierna," various pieces of other tales, and - most pertinently at the moment - "The Soul Cages." But it was a collaborative effort, as "another hand" - i. e., Croker - added details to these stories. Keightley adds that he had nothing to do with Volume 3, "which was apparently intended to rival my Fairy Mythology". Although hinting that he has experienced "hostility" over it, he also says he has "been amused at seeing [himself] quoted by those who intended to praise another person." He dismisses Fairy Legends as a bad depiction of Irish culture and dismissively says that he doesn't really care about getting the credit for such a "trifling" book. There are layers of cattiness here. Croker never explicitly denied that Keightley had authored those stories. His combined volume of Fairy Legends in 1834 left out a number of stories, including "The Soul Cages." The new foreword suggested that the removal of these tales would "sufficiently answer doubts idly raised as to the question of authorship." This contributed to public perception that Keightley really had written the stories he claimed. In an 1849 interview, Croker included Keightley in a list of people who helped him with the book, but indicated that they were essentially secretaries "writing, in most instances, from dictation." However, they were all skilled authors and scholars in their own right, and considering his apparent bow to pressure in 1834, this seems suspicious. Collaboration on folktale collections was not uncommon, but in this case there were clearly both confusion and hard feelings. Keightley did not include "The Soul Cages" or any of his Croker-collaboration material in The Fairy Mythology in 1828. But by 1850, a new edition had appeared. This time, Keightley included an English translation of "The Waterman and the Peasant" - and tucked away in the appendix was "The Soul Cages." Here, as a footnote, Keightley made a stunning announcement: We must here make an honest confession. This story had no foundation but the German legend in p. 259 [The Peasant and the Waterman]. All that is not to be found there is our own pure invention. Yet we afterwards found that it was well-known on the coast of Cork and Wicklow. "But," said one of our informants, "It was things like flower-pots he kept them in." So faithful is popular tradition is these matters! In this and the following tale there are some traits by another hand which we are now unable to discriminate. So here we are. "The Soul Cages" was an original creation by Keightley. More than that, it was plagiarized. It was stolen from the Brothers Grimm and not Irish at all. Keightley has drawn harsh criticism from those who noticed the tiny note. Anne Markey called The Soul Cages "an elaborate confidence trick on Croker, Grimm, and subsequent commentators." (However, she also dated Keightley's confession to an 1878 edition, much later.) But was it a confidence trick? Was it revenge against Croker for not citing his sources - an attempt to discredit him? Was it a test to see if Croker would even notice? Honestly, I'm glad that Keightley confessed, even in the sneaky side way he did it. His confession, hidden in a footnote of an appendix of a later edition, was too little, too late. The story had already spread into the public consciousness, and is still circulated by people who never got that easily missed memo. But at least he told the truth at some late point. He even personally wrote to the Grimms to explain. Or so I'd heard. Then I found out that there are reproductions of Keightley's letters to the Grimms in Volume 7 of the series Brüder Grimm Gedenken. Keightley wrote to the Grimms to ask advice and feedback on The Fairy Mythology. When he mentioned Croker, the level of venom was astounding. He called Croker “a shallow void pretender” and “a parasitical plant.” According to him, Croker couldn't even speak German, and when he had corresponded with the Grimms, it had really been Keightley translating everything. In his version of the story, Croker was working on “a mere childs book” when Keightley suggested something grander; Keightley and friends then generously contributed material for two volumes of Fairy Legends. But Croker (a writer of “feebleness and puerility”) hogged the spotlight and insulted Keightley's writing abilities to boot, calling him simply a "drudge" good for nothing but writing down what he was told. Keightley insisted that he had been "defrauded" of the tales he collected for Legends, and that Croker was still trying to one-up him and compete with him. Keightley quickly realized that his colorful account might be taken as unprofessional. In a letter dated April 13, 1829, he backtracked, demurring that he was just an Irishman with "hot blood" - but reiterating that his version contained the hard facts. He explained further, I know not whether you have translated the 2nd vol. of the Fairy Legends or not. If you have not I cannot blame you for Mr. C. intoxicated with the success of the first volume thought the public would swallow any nonsense & he therefore in spite of me put in some pieces of disgraceful absurdity. The history of the legend called the Soul-cages is curious. I had read, in English, to Mr. C. several of your Deutsche Sagen. One morning he called on me & said that he thought the “Waterman" would make an excellent subject for a tale & that he wished I would write it. I objected that we did not know it to be an Irish legend. “Oh what matter! said he, who will know it? I accordingly wrote the tale which is therefore entirely my invention except the groundwork. You will however except the nonsense-verses & some other puerilities which you will give me credit for not being capable of. But the most curious circumstance is that after the Soul-cage was written I met with two persons from different parts of Ireland who were well acquainted with the legend from their childhood. According to Keightley's version, this was no prank or confidence trick - at least not on his part. Croker had the idea to plagiarize the Grimms. If there are any scenes you think are dumb, it's because Croker added them. But it's actually okay, Keightley says, because people really were telling similar stories in Ireland. If this reproduction of the letter is accurate, then I now feel less sympathetic to Keightley. In his casting of blame, he comes off as immature and two-faced. Keightley may not have published his thoughts on Croker in Fairy Mythology, but he made very sure to always include that he had heard the Soul Cages story in Ireland afterwards. He needed that excuse. Admitting he'd fabricated a story torpedoed his credibility as a folklorist. At least this way he could cling to some plausible deniability. He was practically forced to write the story, he claimed, and afterwards he found out it was genuine anyway. No one can really say whether or not he really heard the story in this later context. Anne Markey suggests the story slipped into folklore after its origins in Croker's book, but this depends on timing. Keightley's public confession was later, but he confessed to the Grimms only two years after "The Soul Cages" was published. That was hardly enough time for the story to have seeped into public consciousness, especially when Keightley's new informants had supposedly known the story since childhood. I do not know of any other stories of this type in Ireland. Thomas Westropp, in his "Folklore Survey of County Clare" (1910-1913), noted that he'd found no other examples of this story in Ireland. He expressed "great doubt" on its authenticity. However, we do have the German tale of "The Waterman and the Peasant," and similar tales from Czech areas. "Yanechek and the Water Demon" ends with the main characters drowning and being collected by the demonic vodník. "Lidushka and the Water Demon's Wife" has a happier ending, in which a girl successfully releases the souls in the form of white doves. These tales were identified as Bohemian in origin in Slavonic Fairy Tales (1874) by John Theophilus Naaké. Elfenreigen deutsche und nordische Märchen, by Marie Timme, an 1877 collection of Germanic-based fairytales, features the melancholy story of "The Fallen Bell." A nix, furious that he no longer receives human sacrifices, drowns a small girl and keeps her soul beneath a sunken bell. These examples point to an origin around Germany and the Czech Republic. They retain a creepy tone which "The Soul-Cages" lost. The villains are explicitly demonic, the trapped souls truly suffering. Meanwhile in "The Soul-Cages," the fisherman remains drinking buddies with the easily duped merman while freeing any souls he catches. Coomara isn’t even an evil being. By his own account, he is just trying to help the drowned souls, and this is supported by the fact that he never does the fisherman or his family any harm. The story is goofy rather than eerie, and the main takeaway is the Irish stereotypes. The tormented history of "The Soul-Cages" betrays the ease with which any folklorist could sneak in a story and claim it was traditional. Everyone was aware of this. Markey points out that Keightley himself highlighted at least two tales of suspicious origin in other collections. Even the Grimms, whom both Croker and Keightley idolized, hadn't really gotten their stories from the German peasant folk, but from middle-class readers of French fairytale collections. The Grimms also made major edits to polish the collection for a public audience. So, in summary:

If you believe Keightley's letter, "The Soul Cages" was not intended as a prank on Croker, or anything of that nature. He said Croker was fully aware of its nature and was the person who came up with the idea. At this point we will never know for sure whether that's true. However, Croker himself pointed out the similarities to the Grimms' story and printed the two tales in the same volume. Publishing your plagiarized work with the original for comparison seems phenomenally stupid. Keightley would probably love to inform us that Croker was exactly that stupid. I still don't know if Croker ever responded to the reveal of The Soul Cages' true origin. Whatever else occurred, I find it interesting that this story gave us the song "The Soul Cages" by Sting. Sources

2 Comments

One classic fairytale is "Le Petit Poucet" by Charles Perrault - often translated in English as Hop o' My Thumb. A poor woodcutter and his wife, starving in poverty, decide to lighten their burden by abandoning their seven children in the woods. The youngest child, Hop o' my Thumb, attempts to mark the way home with a trail of breadcrumbs, but it's eaten by birds. The lost boys make their way to an ogre's house where they sleep for the night. The ogre prepares to kill them in their sleep; however, an alert Hop o' my Thumb switches the boys' nightcaps for the golden crowns worn by the ogre's seven daughters. While the ogre mistakenly slaughters his own children in the dark, the boys escape. Hop also manages to steal the ogre's seven league boots and treasure, ensuring his family will never starve again.

This tale is Aarne Thompson type 327B, "The Dwarf and the Giant" or "The Small Boy Defeats the Ogre." However, this title ignores the fact that there are stories where a girl fights the ogre, and that these stories are just as widespread and enduring. One ogre-fighting girl is the Scottish "Molly Whuppie." Three abandoned girls wind up at the home of a giant and his wife, who take them in for the night. The giant, plotting to eat the lost girls, places straw ropes around their necks and gold chains around the necks of his own daughters. Molly swaps the necklaces and, while the giant kills his own children, she and her sisters escape. Then, to win princely husbands for her sisters and herself, Molly sneaks back into the giant's house three times. Each time she steals marvelous treasures (much like Jack and the Beanstalk). At one point the giant captures her in a sack, but she tricks his wife into taking her place. She makes her final escape by running across a bridge of one hair, where the giant can't follow her. This tale was published by Joseph Jacobs; his source was the Aberdeenshire tale "Mally Whuppy." He rendered the story in standard English text and changed Mally to Molly. In Scottish, Whuppie or Whippy could be a contemptuous name for a disrespectful girl, but it was also an adjective for active, agile, or clever. This story probably originated with a near-identical tale from the isle of Islay: Maol a Chliobain or Maol a Mhoibean. J. F. Campbell, the collector, says that the spelling is phonetic but doesn't provide many clues to the meaning. Maol means, literally, bare or bald. Hannah Aitken pointed out that it could mean a devotee, a follower or servant who would have shaved their head in a tonsure. This word begins many Irish surnames, like Malcolm, meaning "devotee of St. Columba." When the story reached Aberdeenshire, the unfamiliar "Maol" became Mally or Molly, a nickname for Mary. According to Norman Macleod's Dictionary of the Gaelic Language, "moibean" is a mop. "Clib" is any dangling thing or the act of stumbling - leading to "clibein" or "cliobain," a hanging fold of loose skin, and "cliobaire," a clumsy person or a simpleton. Perhaps Maol a Chliobain means something like "Servant Simpleton" - a likely name for a despised youngest child in a fairytale. Maol a Mhoibean could mean something like "Servant Mop." There are a wealth of similar heroines. The Scottish Kitty Ill-Pretts is named for her cleverness, ill pretts being "nasty tricks." The Irish Hairy Rouchy and Hairy Rucky have rough appearances, and Máirín Rua is named for her red hair and beard (!). Another Irish tale with similar elements is Smallhead and the King's Sons, although this is more a confusion of different tales. The bridge of one hair which Molly/Mally crosses is a striking image. This perhaps emphasizes the heroine's smallness and lightness, in contrast to the giant's size. In "Maol a Chliobain," the hair comes from her own head. In "Smallhead and the King's Sons," it's the "Bridge of Blood," over which murderers cannot walk. Based on examples like these, Joseph Jacobs theorized that this tale was Celtic in origin. However, female variants of 327B span far beyond Celtic countries. Finette Cendron is a French literary tale by Madame d'Aulnoy, published in 1697, which blends into Cinderella. The heroine has multiple names - Fine-Oreille (Sharp-Ear), Finette (Cunning) and Cendron (Cinders). Zsuzska and the Devil is a Hungarian version. Zsuzska (whose name translates basically to "Susie") steals ocean-striding shoes from the devil, echoing Hop o' My Thumb's seven-league boots. According to Linda Dégh, female-led versions of AT 327B are quite popular in Hungary. Fatma the Beautiful is a fairly long tale from Sudan. In the central section, Fatma the Beautiful and her six companions are captured by an ogress. Fatma stays awake all night, preventing the ogress from eating them, and the group is able to escape and feed the ogress to a crocodile. In the ending section, the girls find husbands; Fatma wears the skin of an old man, only removing it to bathe, and her would-be husband must uncover her true identity. (This last motif seems to be common in tales from the African continent.) Christine Goldberg counted twelve versions of this tale in Africa and the Middle East. The Algerian tale of "Histoire de Moche et des sept petites filles," or The Story of Moche and the Seven Little Girls, features a youngest-daughter-hero named Aïcha. She combines traits of Hop o' my Thumb and Cinderella, and defends her older sisters from a monstrous cat. This is only one of many African and Middle Eastern tales of a girl named Aicha who fights monsters. And the tale has made its way to the Americas. Mutsmag and Muncimeg, in the Appalachians, are identical to Molly Whuppie. Meg is a typical girl's name, and I've seen theories that the "muts" in Mutsmag means "dirty" (making the name a similar construction to Cinderella). It could also be "muns," small, or from the Scottish "munsie," an "odd-looking or ridiculously-dressed person" (see McCarthy). German "mut" is bravery. (See a rundown of name theories here.) In the 1930s, "Belle Finette" was recorded in Missouri. Peg Bearskin is a variant from Newfoundland. In Old-Fashioned Fairy Tales (1882) by Juliana Horatia Ewing, we have "The Little Darner," where a young girl uses her darning skills to charm and manipulate an ogre. One of the largest differences between the male and female variants of 327B is the naming pattern. Male heroes of 327B are likely to be stunted in growth - a dwarf, a half-man, or a precocious newborn infant. Le Petit Poucet is "when born no bigger than one's thumb" - earning him his name. In English, he has been called Thumbling, Little Tom Thumb, or Hop o' My Thumb. The last name is my favorite, since it helps to distinguish him. Note that despite the confusion of names, he is not really a thumbling character. His size is only remarked upon at his birth. He is thumb-sized at birth, but in the story proper, he is apparently an unusually small but still perfectly normal child. Look at other similar heroes' names:

The names of girls who fight ogres focus on the heroine's intelligence or beauty (or lack of beauty). The heroine is often a youngest child, but I have never encountered a version where she's tiny, as Hop o' My Thumb is. The girl's appearance can play a role in the tale, but if so, the focus is usually on her being dirty, wild or hairy. Where the hero of 327B is shrunken and shrimpy, the heroine has a masculine appearance. Máirín Rua has a beard; Fatma the Beautiful disguises herself as an old man. Outside Type 327B, there are still other female characters who face trials similar to Hop o' my Thumb and Molly Whuppie. Aarne-Thompson 327A, "The Children and the Witch," includes "Hansel and Gretel" (German) and "Nennello and Nennella" (Italian). Nennello and Nennella mean something like "little dwarf boy and little dwarf girl." Nennella, with her name and her adventure being swallowed by a large fish, is the closest to a Thumbling character. Bâpkhâdi, in a tale from India, is born from a blister on her father's thumb - a birth similar to many thumbling stories. In the opening to the tale, her parents abandon her and her six older sisters in the woods. However, after this episode, the tale turns into Cinderella. In Aarne-Thompson type 711, the beautiful and the ugly twin, an ugly sister protects a more beautiful sister, fights otherworldly forces, and wins a husband. This encompasses the Norwegian "Tatterhood," Scottish "Katie Crackernuts," and French Canadian "La Poiluse." It overlaps with previously mentioned tales like Mairin Rua and Peg Bearskin. One central motif to 327B is the trick where the hero swaps clothes, beds, or another identifying object, so that the villain kills their own offspring by mistake. This motif appears in in many other tales, even ones with completely different plots. A girl plays this trick in a Lyela tale from Africa mentioned by Christine Goldberg. In fact, one of the oldest appearances of this motif appears in Greek myth. There, two women - Ino and Themisto - play the roles of trickster heroine and villain. Madame D’Aulnoy’s “The Bee and the Orange Tree” and the Grimms’ "Sweetheart Roland" and "Okerlo" are very similar to 327B. However, they are their own tale type, ATU 313 or “The Magic Flight.” In these tales, a young woman is always the one fighting off the witch or ogre. She’s the one who switches hats, steals magic tools, and rescues others. The main difference is that while the heroes of ATU 327 are lost children, the heroes of ATU 313 are young lovers. But back to the the basic 327B tale. Both "The Dwarf and the Giant" and "Small Boy Defeats the Ogre" are flawed names, given that stories where a girl defeats the ogre are so widespread. These ogre-slaying girls pop up in Ireland, Scotland, Hungary, France, Egypt, and Persia, and have thrived in the Americas. I fully expect to find more out there. Sources

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed