|

The Tyme books are a series of fairytale retellings for kids by Megan Morrison, set in a world co-created with her friend Ruth Virkus. I read all three books in one day; it was the first time in a while I’ve stayed up late reading in bed.

Grounded: The Adventures of Rapunzel is the first in the series and, naturally, a retelling of Rapunzel. The story takes the fairy tale as only a rough guideline; Rapunzel leaves her tower very early on, leading to a road trip with the male lead (Jack, of Beanstalk fame). Grounded makes a lot of storytelling choices that feel very familiar for Rapunzel retellings. I can draw lines to Disney’s Tangled (2010), Marissa Meyer’s Cress (2014), and Shannon Hale’s Rapunzel’s Revenge (2008)... especially Tangled. But it also feels fresh and new, from Morrison’s writing and from the rich and lively world Rapunzel’s exploring. Morrison’s Rapunzel starts out as bratty and spoiled, but even from the beginning she has a kind nature, and we get to watch her grow and mature. The book dives deep into her complicated relationship with the witch (the only mother she’s ever known). Rapunzel and Jack are the leads of the first book, and appear briefly in subsequent books. Disenchanted: The Trials of Cinderella is a very loose retelling, more in homages and references than in plot. The main plot is newly-rich student Ella’s fight for labor rights. Ella has a stepmother and stepsiblings, but they’re not evil; everyone means well, and both they and Ella have some growing and forgiving to do. The fairy godparents are a charitable organization who grant wishes, although they’ve lost their way over the years and Ella’s two godfathers are trying to get back to their original ideals. Glass slippers are the current fashion in the haute couture-obsessed kingdom. There’s a scene where fairy godparents fix up Ella’s gown and shoes so that she can look her best at a mandatory royal ball, and she makes an impression dancing with the prince before later leaving in a rush - but this is a fairly early segment setting us off on the grander plot. Ella's love interest Dash is a fun twist on the concept of Prince Charming; recently freed from a curse which forced him to be charming but insincere, he's a shy and reserved young man re-learning how to interact with people. In contrast to the subtle slow burn in Grounded, Dash and Ella fall fast and hard for each other, and marriage is even mentioned. I wasn’t a huge fan of this considering the age group. Where Grounded was more of a character piece and exploration of a troubled mother-daughter relationship, Disenchanted has a more wide-reaching political plot of Ella fighting against the kingdom’s corruption and the exploitation of the working class. The way everything comes together in the end is pretty fantastic. Transformed: The Perils of the Frog Prince might be my favorite of the trilogy. Remember how I mentioned plot threads and callbacks? In Grounded, Rapunzel gets a pet frog who clearly has something more going on. In Transformed, we learn that the frog is actually the missing Prince Syrah (mentioned in a throwaway line in Disenchanted). This book is a redemption arc. Syrah starts out as an arrogant, thoughtlessly cruel boy who makes a wish on the wrong wishing well and gets hit hard by karma. In a major difference from the fairy tale, frog-Syrah can’t talk, making his quest to break the curse infinitely more difficult. When a mysterious plague starts affecting people, Syrah realizes that as a tiny, overlooked frog, he might be in a unique position to investigate what’s really going on. After the first couple of books, I was expecting a romance; I was pleasantly surprised to realize that this is a very different narrative. Syrah does not get the girl, and a big part of his redemption arc is about accepting that, which I thought was a meaningful message and a good moral for young readers. And as part of that, the second half of the book becomes a buddy cop plot starring Syrah and his ex’s new boyfriend (the only person to figure out who he is and come up with a way to communicate). I loved this plot, and it’s where the story really took off. The complex themes and questions are sometimes more mature than I expected for a Middle Grade novel, and I think it’s suitable for all ages. Morrison builds an elaborate world that feels full of life and adventure (and sometimes a bit silly, like the characters in Disenchanted all having fashion-themed names). Each book is a standalone, but background events hint at more adventures elsewhere in the world and sometimes get unexpected callbacks in later books. There are tons of fairy tale references. Also, the color-themed kingdoms are all parallels to Andrew Lang’s Coloured Fairy Books series (“Cinderella” appeared in the Blue Fairy Book and Disenchanted takes place in the Blue Kingdom; “Rapunzel” was in the Red Fairy Book, and Grounded starts off in the Redlands. I love this so much!) Morrison said at one point on her blog that she planned six books. However, it looks like there hasn’t been any news since Transformed came out in 2019. I don’t know if we will ever see more of the series, which makes me sad. I would love to see Morrison’s take on Sleeping Beauty and find out where the magic acorn subplot was heading. But I'm very glad that at least these three volumes exist. If you’re looking for a fairytale retelling series with some shadow and seriousness to it alongside the quirky worldbuilding, and if you liked series like The Hero’s Guide to Saving Your Kingdom, Half Upon a Time, or (Fairly) True Tales, give these books a read. Also, while on the subject of Rapunzel, I've started a new page for variants of the Maiden in the Tower tale type. Check it out!

0 Comments

The opening of the Italian fairytale "Prezzemolina" is near-identical to Rapunzel, but then the story takes a totally different direction. It becomes something like a gender-flipped versions of stories like "Master Maid" or "Petrosinella," where the hero is in danger from a villain, but is rescued by the villain's beautiful and magical daughter. In this version, it's a heroine who's rescued by the wicked witch's handsome son. There are two primary versions of the tale, so I'll list them in the order of publication.

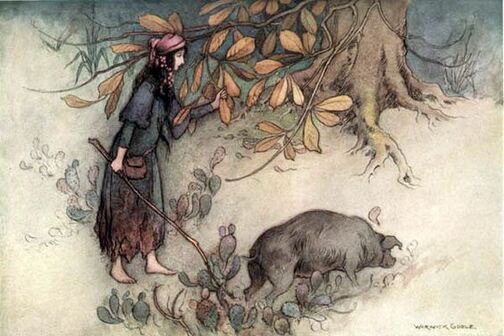

Imbriani's Prezzemolina The story of "La Prezzemolina" begins just like Rapunzel and the older Italian "Petrosinella," with a pregnant woman craving parsley. Some fairies live next door, so she climbs into their walled garden to steal their parsley. They eventually catch her, and tell her that they will one day take away her child. The woman has her baby, who is named Prezzemolina (Little Parsley). The fairies collect her when she reaches school-age, and she grows up as their servant. They give her impossible tasks and threaten to eat her if she fails. Fortunately Memé, the fairies' cousin, arrives and offers to help in exchange for a kiss. She sharply refuses the kiss, but he helps anyway with a magic wand and mysterious powers. She goes through several tasks, including going to Fata Morgana (Morgan le Fay) to collect the "Handsome Minstrel's" or "Handsome Clown's" box, only to open the box and lose the contents. But Memé is always there to assist, and in the end they destroy all of the fairies and get married. The tale appeared in Vittorio Imbriani's La Novellaja fiorentina (1871, p. 121). Italo Calvino, who adapted it in his Italian Folktales (1956), called it "one of the best-known folktales, found throughout Italy." He noted the presence of "that cheerful figure of Memé, cousin of the fairies." This could imply that Memé is a popular folk figure. Imbriani, the original collector, suggested that Memé is Demogorgon, the terrifying lord of the fairies in the 15th-century poem Orlando Innamorato. The name Demogorgon probably came from a misreading of the word “demiurge” in a 4th-century text, and developed to mean either an ancient supreme god or a demon. The biggest similarity I can see is that Fata Morgana plays a villainous role in both “Prezzemolina” and Orlando Innamorato. I’m not sure of Imbriani’s thought process, other than the fact that Orlando vividly describes Demogorgon punishing the fairies. Imbriani also compared Memé to the fairy cat Mammone, who hands out magical rewards and punishments in the fairytale “La Bella Caterina.” Again, I’m not clear on why, except that Memé sounds kind of like Mammone. I may be missing Italian context. In both cases, Imbriani implies that Memé holds some kind of power or authority over the fairies. This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me; Memé seems to be on the same level as the fairies, and is apparently the black sheep of the family. The fairies seem automatically suspicious that he might help a human girl. When they see Prezzemolina’s first impossible task completed, they immediately guess (as Calvino puts it), “our cousin Memé came by, didn't he?" They later tell Meme their plans to kill Prezzemolina, perhaps in an attempt to goad him. Visentini's Prezzemolina Another version, also titled "Prezzemolina," appeared in Canti e racconti del popolo italiano by Isaia Visentini (1879). This version begins with seven-year-old Prezzemolina eating parsley from a garden on her way to school and being kidnapped by the angry witch gardener. Here, the handsome rescuer who only wants a kiss is Bensiabel, the witch's son. This version features different tasks, but one quest still involves retrieving a casket, and in the end Bensiabel kills the witch and Prezzemolina finally agrees to marry him. Andrew Lang published a translation in The Grey Fairy Book (1900), but changed the plant and the name. The vegetable garden became an orchard, the parsley became a plum, and the heroine's name became Prunella. This resembles early translations of Rapunzel where English writers struggled to render the name and came up with "Violet" or "Letitia." However, in this case the reason may be that Lang had already published The Green Fairy Book (1892) with the German tale "Puddocky," which had a near-identical opening with a heroine named Parsley. Lang did not mention a source, but "Prunella" is clearly drawn from Visentini's story. Bensiabel's name may come from the Italian "ben" (well) and "bel" (nice). This seems supported by the French translation, Belèbon, in Edouard Laboulaye's 1881 retelling "Fragolette." Belèbon may be from the French "bel" (attractive) and "bon" (good). Like Lang, Laboulaye turned the parsley into a fruit, in this case strawberries (Italian fragola). Cupid and Psyche As Calvino implies, there are a number of similar tales. Charlotte-Rose de la Force - the author who gave us the modern Rapunzel - also wrote a story in 1698 called "Fairer-than-a-Fairy" which followed some of the same motifs as Prezzemolina. The heroine, Fairer-than-a-fairy, is kidnapped by Nabote, Queen of the Fairies. Nabote's son Phratis falls for Fairer and helps her. Calvino published another tale with similar plot beats, titled "The Little Girl Sold with the Pears" (p. 35), noting that he made numerous edits. The original, "Margheritina," collected by Domenico Comparetti, is even closer to Prezzemolina, with the heroine's unnamed prince being the one to magically aid her. Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 425, The Search for the Lost Husband, is a large family of tales with many subtypes. 425C is Beauty and the Beast. In the current breakdown, 425B is "The Son of the Witch." When Hans-Jorg Uther codified this, he wrote "The essential feature of this type is the quest for the casket, which entails the visit to the second witch’s house. Usually the supernatural bridegroom is the witch’s son, and he helps his wife perform the tasks." In the Pentamerone (1634-1636) is a story titled "Lo Turzo d'Oro" - literally "The Trunk of Gold," but also titled "The Golden Root" in translation. When the heroine Parmetella is completing her tasks to win back her husband Thunder-and-Lightning (Truone-e-llampe), he helps her through each task. This is the bloodiest variant I've read. Laura Gonzenbach's story "King Cardiddu" also features a male character who's imprisoned by the villain but manages to provide magical help to the heroine. Giuseppe Pitre collected a Sicilian tale called "Marvizia" (Fiabe, novelle e racconti popolari siciliani, 1875). The heroine is named for her resemblance to a "marva" or mallow plant. The villain is an ogress named Mamma-Draga. It's a long and elaborate tale, but in a section similar to Prezzemolina's quests, Marvizia is assisted in her tasks by a giant named Ali who works for Mamma-Draga. However, he's not the love interest; Marvizia marries a captured prince whom the villainess turned into a bird. (This story features an ogress who eats people "like biscotti," and the hero wishes for a literal bomb with which to blow up her castle. I just felt that was important to note.) "Cupid and Psyche," recorded in the second century, is the uber-example. Psyche loses her divine husband Cupid and must complete her goddess-mother-in-law Venus's tasks to get him back. Although the tasks are meant to be impossible, Psyche completes each one with help from nearby creatures. Finally she must go to the Underworld and retrieve a box from Persephone, but foolishly opening it, falls into a deep sleep. At this final point, Cupid steps in and rescues her. Prezzemolina and similar tales are neighbors of the "Cupid and Psyche" tale - related to stories like "East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon." They don't have the beastly transformation, or the scene where the love interest is about to be forced to marry the wrong girl. However, they share the motif of the girl faced with impossible tasks including retrieving a magical box, and being aided by her supernatural lover. Taken to its furthest conclusion, this casts interesting parallels from Prezzemolina to Beauty and the Beast tales. Beauty's father is forced to hand his daughter over because he stole a flower from the Beast's garden - a very Rapunzel moment. Prezzemolina's suitor constantly begs for a kiss, the Beast asks Beauty to marry him, and the Frog Prince requests to sleep on his princess's pillow. Memé and Bensiabel would then be related to Cupid and the family of beastly bridegrooms. Echoing Cupid, they're benevolent sorcerers or minor deities smitten with a mortal girl, who defy their divine or monstrous mothers to help. Unlike the lost husband figure, the Memé figure is never under a curse, and is right there alongside the heroine for the whole tale. She has no need to pursue him, because he's wooing her the entire time. With its unique mix of fairytale tropes, I'm not sure whether the Prezzemolina type would be best categorized as 425B, "The Son of the Witch," as 310, "The Maiden in the Tower," or as something else entirely. Other Blog Posts What plant was Rapunzel named for? In the original German, the food that her mother desires is "rapunzel," plural "rapunzeln," but the proper English translation remains mysterious. One writer gave up with the pronouncement that "hardly anybody has the least idea what rampion is or looks like, though it is clearly some kind of salad vegetable" (Blamires, Telling Tales, 161).

This is not entirely true. The problem is that we have several ideas. Multiple plants are known, in German, as rapunzel. I have come across four that are frequently attributed as the plant of the fairytale.

The only clue we really have from the story is that the pregnant woman eats it in a salad, and that perhaps her craving seems a little strange. Any of these plants would fit that description. In fact, the name Rapunzel is actually a unique addition by Schulz. In the older and more widespread tales from France and Italy, as we've looked at over the past few weeks, the plant is parsley. This is reflected in the names of various heroines: Petrosinella, Persinette, Prezzemolina, Parsillette, and others. In the Italian "Petrosinella," the oldest known Rapunzel tale, there is no explanation needed for the parsley. It is used to flavor the tale with innuendo. In "Persinette" (1698), Charlotte-Rose de Caumont La Force explains that "In those days, parsley was extremely rare in these lands; the Fairy had imported some from India, and it could be found nowhere else in the country but in her garden." Parsley is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean, but would still have been familiar to La Force's audience. The herb had been in France for a long time. Charlemagne and Catherine de Medici, for instance, had it in their royal gardens. La Force's fanciful explanation of the rare parsley places the story in a distant land and/or time. There's also a wry little comment about the wife's unusual hunger: "Parsley must have tasted excellent in those days." Schulz approached the tale nearly a hundred years later in his collection of tales, Kleine Romane. His translation of "Persinette" contains various small changes, but the most significant was that he changed the plant, and with it, the girl's name. In his translation, the fairy's garden includes "Rapunzeln, which were very rare at the time. The fairy had brought it from over the sea, and there was none in the country except in her garden." There is still the comment "back then the Rapunzeln tasted wonderful." Schulz's "Rapunzel" was the version which influenced the Brothers Grimm (who were apparently unaware of the French fairytale). Their first version of Rapunzel is very terse and simple, in line with oral storytelling, so it's likely that they were relying on an informant who had read Schulz. If not for Schulz's creativity, we might today have an alternate fairytale chant of "Petersilchen, Petersilchen, let down your hair!" So this whole question of plants must begin from a different place - because it wasn't Rapunzel to begin with. The meaning of parsley In the older stories, parsley was rich with symbolism, associated with desire and fertility. The Greek physician Dioscorides wrote that parsley "provokes venery and bodily lust." The story of "Petrosinella" relied on this; there is a salacious line about the prince visiting the girl to enjoy the "parsley sauce of love." English children were told that babies were found in parsley beds (Folkard, Waring). According to Waring's Dictionary of Omens and Superstitions (p. 174), "Some country women still repeat an old saying that to sow parsley will sow babies." In another superstition, too much parsley in your garden would mean that "female influences reigned" and only baby girls would be born! (Baker, 1977) Occasionally it could be dangerous. In Greece, parsley was a funerary herb and had associations with death. Richard Folkard mentioned an English superstition that transplanting parsley would offend "the guardian spirit who watches over the Parsley-beds," leading to ill fortune. (Hmmm... very fitting for the Rapunzel story.) Parsley featured in many folk remedies. It was used on swollen breasts and in cures for urinary ailments. According to Thompson, "A craving for parsley of the mother would make immediate sense" due to its use in traditional medicine (pp. 32-33). It was also used by midwives to speed up labor when a mother was struggling with a long childbirth, and in the early stages of pregnancy, it could be used as an abortifacient. Much has been made of the abortion possibility in connection with Rapunzel. This particularly colors Basile's version, where Petrosinella's father is never mentioned, and her mother acts alone in stealing parsley from the ogress's garden. However, in "Persinette," La Force gives us a married couple who do want children but still ultimately give up their daughter in exchange for the precious parsley. Why? Well, abortion is not parsley's only connection; look at all the other beliefs surrounding parsley and fertility. It could also indicate that the mother was sickly or facing a difficult childbirth. Also, don't forget just how much importance was placed on pregnancy cravings. Pascadozzia, for instance, claims to fear that her child will have a disfiguring birthmark if she doesn't obey her cravings. See Holly Tucker's Pregnant Fictions for more on just how drastic these ideas could get, and how much sway pregnant women held. Persinette's parents may have seen no other option, with the lives of both mother and child potentially on the line. If not parsley, another symbolic plant typically features in Rapunzel-type tales: herbs such as fennel, or fruit such as apples. There are levels of erotic symbolism. A pregnant woman lusts uncontrollably after a food associated with desire. Her child is named for that food and grows up locked away to keep her from male advances. Even so, her guardians are never able to prevent her from eventually becoming sexually active when she reaches maturity. Her name and her nature are linked. Why the Change? Swapping rapunzel for parsley boots all of those superstitions, folk remedies, and symbols. Why exactly did Schulz change it? Here are some theories I've come across: Theory 1: Rapunzel would have made more sense than parsley to a German audience. Kate Forsyth's excellent case study The Rebirth of Rapunzel suggested that "Schulz may have changed the heroine’s name because parsley is a Mediterranean plant that grows best in warm, temperate climates, and so may have been relatively unknown in northern Germany, where Schulz was born." In the exact opposite direction, writer Gabriele Uhlmann concluded that the plant was lamb's lettuce, based on the statement that rapunzeln was rare, and the fact that lamb's lettuce was imported to Germany. Note that the line about the plant being rare is a direct translation of La Force's joke. Either way, both of these theories rely on the idea that rapunzel would have made more sense than parsley - either more familiar, or more rare and alluring, to a German audience. What do German books of the time indicate? Johann Jakob Walter's Kunst- und Lustgärtners in Stuttgart Practische Anleitung zur Garten-Kunst (1779) does feature parsley under the German names petersilie and peterling, with instructions for growing it in gardens. Walter also listed three rapunzels - Campanula rapunculus (rampion bellflower), Oenothera biennis (evening primrose), and finally Phyteuna spicata (spiked rampion) - while mentioning that there were still others out there. He differentiated them by calling them blue-flowered Rapunzel, yellow-flowered Rapunzel, and forest Rapunzel. He attributed Oenothera biennis as an American plant, but I got the impression that he was familiar with the other two plants growing wild in Germany. Joachim Heinrich Campe's 1809 book Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprach lists numerous plants as Rapunzel. Campanula rapunculus is first, but attributed to Switzerland, France and England. Next are Phyteuna spicata and Valerianella locusta (lamb's lettuce), both attributed to Germany. Finally is Oenothera biennis. He notes the first three as frequently eaten in salads. This doesn't help much. All I can say is that when Schulz was writing, parsley was known in Germany, and so were multiple plants known as rapunzel. Perhaps there's a clue in other fairytales. In 1812 - writing 22 years after Schulz - we have Johann Gustav Büsching's story "Das Mahrchen von der Padde," or "The Tale of the Toad," in Volkssagen, Märchen und Legenden. In this Rapunzel-like tale, the parsley-munching heroine is named Petersilie. So we have another German collector from roughly the same era, collecting a similar tale, who did not see any problems with keeping a character named Parsley. He didn't seem to worry that German readers would find parsley too faraway or too mundane. It was evidently a story native to Germany, parsley and all. (However, an English translator, Edgar Taylor, altered the name to "Cherry the Frog Bride" - presumably to make the name prettier.) Theory 2: Schulz was intentionally trying to erase the symbolism of parsley, particularly its use as an aphrodisiac and/or abortifacient. Personally, I doubt that Schulz was trying to erase erotic symbolism from the story. I also doubt that he was trying to erase female agency - yes, that's a theory I've run into. It's true that the Grimms made edits and removed things they didn't feel were appropriate. But they weren't the ones who changed the plant! Schulz's edits consisted mostly of adding his own little details to explain plot holes or color the story. He kept the story as La Force wrote it, including the pregnancy as well as the strict but ultimately loving fairy godmother who reunites with Rapunzel at the end. There is no erasure of eroticism going on here. There is no demonizing of the older, magical woman. The Grimms - who had exactly nothing to do with the Rapunzel name - were the ones who edited out the unwed pregnancy and transformed the benevolent fairy into a nasty old witch named Mother Gothel. Even then, while their edits made Rapunzel dangerously foolish, they also gave her an element of agency that neither La Force or Schulz gave her: the Grimm Rapunzel actively tries to run away from Gothel, weaving a ladder to escape her tower. Theory 3: Schulz thought Rapunzel was a cooler name than Petersilchen (the direct translation of Persinette). This is another theory brought up by Forsyth: perhaps Rapunzel was more appealing to Schulz's ear. Swiss scholar Max Lüthi wrote that "Rapunzel sounds better in the German tale than Persinette, it has a more forceful sound than Petersilchen... To be sure , in folk beliefs the plants called 'Rapunzel' do not play any important role, quite in contrast to those... such as parsley and fennel, apples and pears, which are attributed eroticizing and talismanic properties" (as quoted in McGlathery, Fairy Tale Romance, p. 130). Perhaps there's a clue in other translations. Schulz was not the only one to make edits to a literary tale which he was presenting to the audience of another country. When it came to exporting the Grimms' tales, English translators were faced with some problems. Most chose to keep Rapunzel's name. A valid choice, but one that leaves the name meaningless to English-speakers. Rapunzel just isn't familiar as a plant name to a lot of Americans. As Forsyth put it, "the change of the heroine’s name to Rapunzel drained much of the symbolic meaning from the herb, and in many cases led to the link between girl and plant being broken." In the most drastic departure, John Edward Taylor translated Rapunzel for The Fairy Ring: A Collection of Tales and Traditions in 1846 . . . as "Violet." Rather than craving salad, the mother demands her own bouquet of the sweet-smelling violets that only grow in the fairy's garden. Taylor stripped the fairytale of even more symbolism, made the heroine's name mundane and ordinary, and made her parents dangerously stupid and greedy (really . . . the wife demands a fresh bouquet every day, even though she can see and smell the violets from her window. And she's not even eating them). Martin Sutton, attributing Valeriana locusta as the original rapunzel, suggested that Taylor was avoiding not only the implications of pregnancy and cravings, but a possible link to the drug valerian, used for anxiety and sleep disorders. Fortunately, "Violet" did not catch on. An anonymously translated 1853 English version, Household Stories Collected by the Brothers Grimm, changed the plant to radishes but kept the Rapunzel name without explanation. H. B. Paull published Grimm's Fairy Tales in 1868, with the story under the title of "The Garden of the Sorceress." In a stroke of brilliance, she translated rapunzeln as lettuce and named her heroine Letitia, "Lettice" for short. Home Stories, in 1855, described the plant as "the most beautiful rampions." Mrs. Edgar Lucas used the translation corn-salad in Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (1900). Corn-salad, again, is an alternate name for Valerianella locusta or lamb's lettuce. In the 1909 edition, however, she changed the plant to rampion. Throughout all translations, rampion gradually took over in English as the most common translation. Otherwise, translators tended to leave it as "rapunzel." Conclusion The answer to the change lies with Schulz. So who was Schulz? What kind of translator was he? Was he a Taylor, a strict prude who wanted a pretty and innocent plant? Was he a Paull, with a hand for wordplay? I think Schulz was simply a storyteller. He stayed faithful to La Force's story, but he added small details, spicing it up rather than doing a flat translation. For instance, La Force simply says that Persinette had good food, but Schulz gives Rapunzel a detailed meal including marzipan. He also adds that Rapunzel doesn't just let her hair down, but winds it around a window hook before allowing people to climb it. When Rapunzel's prince goes missing, the king is left worrying about the succession of the kingdom. In essence, Schulz liked include practical little details that made the story more realistic and immediate. "Parsley" might have been all right for another collector, such as Büsching, but it didn't cut it for Schulz. I think all three theories for Rapunzel's name change are valid, and they could work together without conflicting. Schulz could very likely have preferred the sound of Rapunzel to Petersilchen. Maybe he did think it would make more sense than parsley to his German audience. And with his practical side, maybe he knew parsley could pose a danger to pregnancy; he may have thought that didn't suit La Force's story, in which a happily married woman eagerly awaits her firstborn child. This still leaves the question of which rapunzel he meant. There were at least four he might have heard of. We know that La Force's parsley and Schulz's rapunzel are eaten in salads, and that they would not be considered all that delicious (see the joking remark that parsley must have tasted wonderful back then). Both parsley and multiple plants known as rapunzel could be found in German gardens of the time. I've never had the opportunity to do a taste test of these plants; the only one I've ever had is parsley as a garnish. I did start looking at images of the plants. Campanula rapunculus (rampion bellflower) and Oenothera biennis (evening primrose) are flowers. Phyteuma spicata (spiked rampion) has tall stalks topped with bristling spearheads. By process of elimination, Valerianella locusta - lamb's lettuce - looks the most similar to parsley. Not very similar - their leaves look very different - but both are leafy green vegetables. And both of them blossom with bunches of teeny-tiny whitish flowers. When I looked at pictures of them flowering, I instantly thought "That has to be it." Another note: we don't know what Schulz was thinking, but we may have an idea what the Grimms were thinking. The mother in the Grimms' "Rapunzel" is struck by the sight of the "fresh and green" vegetable when she sees it from a distance. The narrative is not entirely clear, but it does indicate that she wants the leaves in her salad and they are the main focus of her desire. Two things here: 1) Rampion bellflower and spiked rampion have edible leaves, but are primarily grown as root vegetables. 2) Rampion bellflower (again) and evening primrose would have been most recognizable by their blue or yellow blossoms, not by green leaves. Again... that leaves lamb's lettuce. In addition, the Grimms originated a dictionary series, "Deutsches Wörterbuch." In an 1893 edition, published after their deaths, rapunzel is defined first as "die salatpflanze valeriana locusta, feld-lattich." Lamb's lettuce. The others come in second. Evening primrose doesn't even make it into the entry - it gets listed on its own as "rapunzelsellerie." So why did rampion take over as the English translation of rapunzel? Out of the English options, rampion has the most visual similarity to "rapunzel." It also has perhaps a slightly more romantic look to it. You can't name a fairytale princess "Corn Salad." Or you could, but it would be a brave choice. Quite a few translators struggled with the name, as seen in "Violet." In addition, English and American translators may simply not have been familiar with German garden vegetables. The other plants all have their points or bring intriguing connections to the story. However, I believe the rapunzel plant is most likely Valerianella locusta - lamb's lettuce or corn salad. Personally, I'd love to read a study of the tale from a German botanist. Further Reading

And more So far, in examining the history of Rapunzel, we have seen two very different endings to the Maiden in the Tower tale.

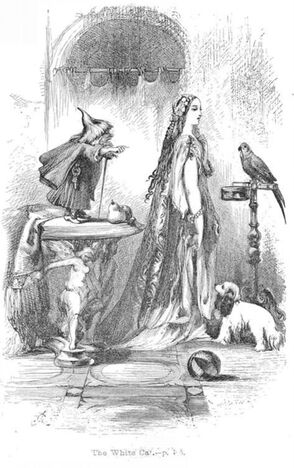

In the literary La Force/Grimm ending, Persinette/Rapunzel's hair is cut, the prince falls from the tower and goes blind, and they reunite later in the wilderness where her tears cure his blindness. But in the older and more widespread ending, derived from oral tradition, the boy and girl flee from an ogre's chase in a "magical flight" where they use enchanted tools to evade the monster. Rapunzel is Aarne–Thompson Type 310, "The Maiden in the Tower." The oldest known Rapunzel, "Petrosinella," fits this, but is also close to Type 313, "The Girl Helps the Hero Flee." Type 313 tends to feature tough, clever heroines who use magic to get their boyfriends out of trouble and run circles around the villain. Italian Rapunzels - or more properly, Parsleys - are clever and magically powerful. Italian Rapunzels Although Basile's version is a literary tale, there are many examples of the tale in collected Italian folklore. "Snow-White-Fire-Red," recorded in 1885, overlaps with AT 408, "The Three Oranges," with its strikingly colored heroine, the prince on a hopeless search for her, and their separation when he forgets her. It lacks the significant Rapunzel "garden scene" of stolen vegetables. However, it still has the the tower, the ogress, the hair-ladder, and the heroine's use of magic to escape with her prince. In the end, the ogress curses the prince with amnesia, and Snow-White-Fire-Red has to get him to remember her. There is a Greek version titled "Anthousa, Xanthousa, Chrisomalousa" (Anthousa the Fair with Golden Hair). Some stories feature the "garden scene" beginning of Rapunzel, but are actually different tale types. Italo Calvino, in his Italian Folktales (1956), includes "Prezzemolina" (meaning, again, Little Parsley). There is no hair or tower, but instead a parsley-loving girl forced to serve a witch until her magician boyfriend rescues her. Variants on this are Prunella (Plum) and Fragolette (Strawberry). "The Old Woman of the Garden" has the same opening, but there is no prince at all. Instead, the girl shoves the witch into her own oven and goes home to her mother. French Rapunzels In Italian versions, the ogress is dangerous and powerful, but the girl is powerful too. By contrast, French versions make the heroine and hero totally defenseless before the fairy's or ogress's might. La Force may have created an original ending to the tale, but the touch of tragedy ties in with oral French equivalents. The heroes are passive, with Persinette's only ability being her healing tears; the fairy wields all the power, and they get their happy ending when she feels sorry for them. "Persinette" is actually an exception from some French relatives in that it ends so happily! Revue des traditions populaires, vol. 6 (1891) featured a French version called Parsillette (you guessed it - Little Parsley). This tale has so many similarities to Persinette that it may have been influenced by it, except for the addition of a talking parrot who betrays Parsillette's secret. Except that in the end, Parsillette is struck with ugliness by her godmother's curse. She hurries back to beg her godmother's forgiveness and plead for her beauty back, seemingly unconcerned that her boyfriend has dropped dead. It ends abruptly: "Later Parsillette married a very wealthy prince, and she never knew her parents." "The Godchild of the Fairy in the Tower" is another strange one, very short, and apparently influenced by literary versions of the story. A talking dog, rather than a parrot, betrays the secret. At the godmother's curse, the unnamed golden-haired girl becomes a frog, and the prince grows a pig's snout. The End. I'm not making this up. You could trace tragic endings as far back as the Greek myth of Hero and Leander, where the hero drowns trying to swim to his lover's tower prison, and she then commits suicide. Or there's the third-century legend of Saint Barbara, where the tower-dwelling heroine discovers Christianity (making Christ, in a way, her prince) and becomes a martyr at her father's hands. However, the odd little tale of "The Godchild" reminds me of another tale, where a Rapunzel-like character ends up in a tale similar to the Frog Prince. Puddocky This is a German tale, "Das Mährchen von der Padde" (Tale of the Toad), adapted by Andrew Lang as "Puddocky." A poor woman has a daughter who will only eat parsley, and who receives the name "Petersilie" as a result. In the German version, Petersilie's parsley is stolen from a nearby convent garden. The abbess there does nothing until three princes see the girl brushing her "long, wonderful hair," and get into a brawl over her right there in the street. At that point, the infuriated abbess wishes that Petersilie would become an ugly toad at the other end of the world. (Interestingly, Laura J. Getty points out several traditional versions of the Maiden in the Tower where the girl's caretaker figure is a nun.) In Lang's version, instead of an abbess there's a witch who takes Parsley into her home. Lang also specifies that Parsley's hair is black. From there, in both versions the enchanted toad breaks her curse by aiding the youngest prince in his quest for some enchanted objects. She becomes human again and they marry. It's an example of the Animal Bride tale, albeit with a beginning reminiscent of Rapunzel - a similarity which Lang enhanced by turning the abbess neighbor into a witch foster mother. "Blond Beauty" is a very short French version which, like Parsillette, has a parrot reveal the girl's affair. There's also a much longer and more elaborate literary version from France: The White Cat A tragic Rapunzel tale is embedded in Madame D'Aulnoy's literary tale of the White Cat, another Animal Bride tale, published in 1697 - the same year as "Persinette," by an author from the same circle. Late in the story, after the magical quest and curse-breaking parts are over, the heroine explains how she came to be cursed. Her mother ate fruit from the garden of the fairies, and agreed to let the fairies raise her daughter in exchange. The fairies built an elaborate tower for the heroine, which could only be accessed by their flying dragon. For company, the heroine had a talking dog and parrot. One day, however, a young king passed by, and she fell in love with him. She convinced one of the fairies to bring her twine and secretly constructed a rope ladder. When the king climbed up to her, the fairies caught him in her room. Their dragon devoured the king, and the fairies transformed the princess into a white cat. She could only be freed by a man who looked exactly like her dead lover. Rapunzel as a "Beauty and the Beast" Tale "Puddocky" and "The White Cat" focus more on the animal transformation than on the "Maiden in the Tower" elements. They keep Rapunzel's "garden scene," but the main plot is of a prince encountering a cursed maiden in a gender-flipped Beauty and the Beast tale. Not all "Animal Bride" tales (AT type 402) have this overlap with Rapunzel, but quite a few Rapunzel tales feature the maiden losing her beauty in some way. Laura G. Getty mentions other versions which start out like Petrosinella, with the flight from the ogress, but which then feature an additional ending where the ogress curses the girl to have an animal's face. They have to convince the ogress to take back the curse before a marriage can take place. An Italian example is "The Fair Angiola," cursed to have the face of a dog. The Complete Rapunzel Put everything together from all the versions, and a much more elaborate version of Rapunzel emerges:

Take out a few scenes here or there, and you can get all sorts of combinations. Delete the animal transformation and separation and you've got the Italian Petrosinella. Focus on the transformation and leave out the magical flight, and you have the German Puddocky. Remove the happy ending and you have "The Godchild of the Fairy in the Tower." Keep it all together and you have, more or less, "Fair Angiola." Even with La Force's unique creative twists, I was surprised to see how much Persinette matched up with other tales. The temporary loss of her prince and exile in the wilderness is a common trial. The fairy cutting Persinette's glorious hair is parallel to the traumatic transformation in other stories. In versions like “Parsillette" or “The Fairy-Queen Godmother,” the fairy is the source of the heroine’s wondrous beauty and removes it when the heroine runs away. Persinette’s godmother also bestows beauty (including presumably her unique hair) at her baptism. When she cuts off Persinette's hair, she is removing her goddaughter's special privileges and gifts. This is accompanied by a change in location: instead of a bejewelled silver tower, Persinette now lives in an even more isolated house. This dynamic is quite different from laying a curse of animal transformation. However, the implications are lost in the Grimms' retelling. I find it interesting that there are many versions where the girl isn't just transformed, but where she needs to heal (or perhaps resurrect?) the prince. Persinette cures her prince's blindness. Snow-White-Fire-Red and Anthousa fix their princes' amnesia. The White Cat and Parsillette replace their dead princes with suspiciously similar doppelgangers. If "The Godchild of the Fairy in the Tower" continued, one presumes that the heroine would need to not only break her own curse but cure her prince of his pig snout. In all this, the witch-mother is a mysterious and morally grey character. Angiola's witch is a generous guardian who releases her from her curse, but is also a predatory figure (biting a piece from Angiola's finger at one point). The White Cat's fairy guardians are more malicious, pampering her but also being demanding and violent. Often the witch is merely a force to be evaded or killed. But also fairly frequently - as seen in Angiola, Blond Beauty, The Fairy-Queen Godmother, and Persinette - she does fully reconcile with the heroine and release her from her curse. In "Anthousa, Xanthousa, Chrisomalousa," rather than cursing the prince, the ogress warns Anthousa that he'll forget her and gives her the instructions to win him back. Conclusion Rapunzel is, at its core, a tale of an overprotective parent hiding away a maturing daughter so that she won’t encounter men. Some versions make her female guardian a nun - reminiscent of young noblewomen being sent to a convent to guard their virginity until they were of age to marry. Elements of desire and lust show through in the early garden scene, with the suggestive elements of the pregnant woman’s unstoppable cravings for parsley (an herb accompanied by erotic symbolism). In the story of Puddocky, the girl herself is the one obsessed with the food. The idea of forbidden fruit in a garden leading to sin is as old as the story of Adam and Eve. This beginning sets up the path of sexual temptation which Parsley is locked away to avoid, but her very name hearkens back to it. Although the heroine typically ends up married despite her parent-guardian’s best efforts, she must endure trials before finally marrying her lover. These trials are directly related to her disapproving guardians, who did not bless the marriage. The emphasis on family approval is evident even in the early tale of Rudaba. In the case of Parsillette, she leaves her boyfriend, begs her godmother to take her back, and submits to an arranged marriage, restoring her to societal status quo. Less exciting, but possibly more realistic. And in "The Godchild," both lovers are simply out of luck. La Force gave Persinette the happy ending found in Mediterranean versions, and a reconciliation with the parental figure more common in French versions. But she did so while explicitly showing that the fairy was trying to protect Persinette from a bad fate, apparently out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Other writers nodded to Parsley’s activities with the prince – Basile had the prince visit Petrosinella at night to eat "that sweet parsley sauce of love," a line that gets removed in a lot of versions. But La Force, uniquely, had that relationship lead to the natural result: pregnancy. The Rapunzel tale type could be a romantic story of a girl escaping her strict family and running away with the boy she loves. However, the additional ending served as an extra cautionary fable for young noblewomen of the time, in a patriarchal society where they had little power. The story doesn't end with running away together and enjoying the "parsley sauce of love." The heroine has squandered the wealth and gifts of her family. She's no longer a virgin. Maybe she's even pregnant. What if she loses her beauty? What else can she offer as a bride? The boy is the one with power in the relationship; what if he forgets her and plans to marry someone else? She may have to fight for him. She may end up alone in poverty. But quite a few stories serve as reminders that her family may still be open to reaccepting her. Even with the eventual happy ending, in the era the stories were told, a young noblewoman who made the same choices as Parsley would undergo significant hardships. Stories

Analyses

And more: The Brothers Grimm's Rapunzel is actually a rather unusual tale. It's an example of the tale type called "The Maiden in the Tower," but it's far removed from its roots among oral folktales, marked by the creative additions of a French author.

Worldwide, the image of a virginal young woman trapped in a tower has been persistent for millennia. Graham Anderson, in Fairytales in the Ancient World, attempts to tie Rapunzel to a fragmentary Egyptian story called "The Doomed Prince," in which a prince accesses his beloved's tower by jumping (pp. 121-122). Rapunzel has also been compared to the legends of Hero and Leander, or Saint Barbara. There's a clearer ancestress in the Persian epic Shahmaneh, written around 1000 AD. This work features a woman named Rudaba (River Water Girl), locked in a tower by her father. Despite this barrier, she falls in love with a man named Zal. In a very sweet scene, she offers Zal her long hair: "Come, take these black locks which I let down for you, and use them to climb up to me." But he says in horror that he doesn't want to hurt her, and instead obtains a real rope. They eventually convince their families to let them marry, and their son becomes a great hero. Are later versions an exaggeration of Rudaba's invitation to let someone climb her hair? Or was the writer playing on an oral tale where a man did climb a woman's hair, by pointing out that it would be painful? Either way, the scene suggests a seed of the story that would one day become Rapunzel. Petrosinella "Petrosinella" is usually cited as the oldest known tale identifiable as a Rapunzel type. This was an Italian literary tale published in 1634 by Giambattista Basile. It all begins when a pregnant woman named Pascadozzia sees "a beautiful bed of parsley" in an ogress's garden. Overcome with ravenous hunger, she waits until the ogress is away and then breaks in to steal some of it - multiple times. The ogress threatens her with death unless she hands over her child. The child, Petrosinella (Little Parsley) actually reaches seven years old before before the ogress nabs her and takes her to a distant tower. This tower is accessible only by climbing Parsley's long tresses of golden hair. A prince finds her, they fall in love . . . and then Petrosinella takes complete charge of the story. She steals three magical gall-nuts from the ogress and runs away with the prince. The ogress pursues them, but Petrosinella throws the nuts onto the ground, where they become a dog, a lion, and a wolf who delay the ogress and finally gobble her up. Petrosinella and her prince live happily ever after. I remember finding Rapunzel a rather pathetic figure when I read the story as a child. She just sat in her tower, unable to figure out how to escape when it was most important. Why didn't she find a rope, or cut her hair and use that? Where was this Rapunzel, flinging magical nuts and summoning monsters? More than fifty years after Basile, the next step appeared, and the story changed. Persinette The French aristocrat Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force was among other women writing literary fairytales in the 17th centuries. They took inspiration from oral folktales, but put their own spins on them and used them to comment on their society at the time. La Force's story "Persinette" was published in 1697 in a book titled Les Contes des Contes. Persinette is derived from the French word "persil," meaning Parsley . . . so, "Little Parsley." It begins in a manner very similar to Petrosinella, but then sets out on its own path. For one thing, rather than a pregnant woman alone, de la Force gives us a couple expecting a child. It is the father, not the mother, who goes stealing parsley on his wife's behalf, and he's the one who's caught by the fairy owner of the garden. Instead of threatening him with death, the fairy offers him all the parsley he wishes if he will hand over his unborn child. The man agrees. The fairy acts as godmother, names the child and swaddles her in golden clothing, and sprinkles her with water that makes her the most beautiful creature alive. However, the fairy knows Persinette's fate and is determined to avoid it, so when the girl turns twelve the fairy hides her in a bejewelled silver tower filled with every luxury imaginable. When the fairy visits, she does so by climbing up Persinette's conveniently tower-length blonde hair. The story is exactly what you may remember: a prince hears Persinette singing and falls in love with her, eventually copies the fairy to climb up to the tower via hair, and their romance leads to pregnancy. The fairy is furious that her attempts to safeguard Persinette have been flaunted by Persinette herself. She cuts off Persinette's hair and sends her to a comfortable but isolated home deep in the wilderness. When the prince discovers his love gone and hears the fairy's taunts, he throws himself off the tower in despair. He doesn't die, but loses his sight. He wanders for years, until one day he happens on the house where Persinette lives with her young twin children. When Persinette's tears fall on his eyes, he regains his sight. However, the happy family realizes that the food around them (previously provided by the fairy) now turns into rocks or venomous toads when they try to eat, and they will surely starve. Despite this, Persinette and the prince affirm their love for one another. At this point the fairy takes pity on them, and carries them in a golden chariot to the prince's kingdom, where they receive a hero's welcome. It's a clear descendant of older tales. The beginning is that of Petrosinella. The maiden hidden in a tower to keep her from men, who becomes pregnant anyway and is cast out by her parent, also features in the Greek myth of Danae. But many of the most striking details - Rapunzel's forced haircut, the prince's blindness, the twin babies, and the healing tears - are all original creations by La Force. Our modern Rapunzel comes directly from her unique original fairytale. German translations of Persinette In 1790, a century later, Friedrich Schulz published a German translation of Persinette in his book Kleine Romane. It's not clear exactly how he encountered it, but it is very clearly a translation of La Force's story. His most significant contribution was to change the heroine's name. Rather than translating it to Petersilchen, the German equivalent of "Little Parsley," he replaced the coveted parsley with the salad green rapunzeln. The girl's name thus became Rapunzel. Then along came the Grimms. Although their goal was supposedly to collect the oral tales of Germany, their sources were typically middle-class families who'd read plenty of French fairytales. They ended up removing some of their stories upon realizing that they were clearly French literary tales (anyone heard of "Okerlo"?). But some stories stuck around which modern scholars now believe were not German in origin at all. The Grimms' first version of Rapunzel, in 1812, was very short and simple, almost terse. However, it reads like a summary of Schulz, including his unique use of the name "Rapunzel," indicating that their source was someone who had read Schulz's "Rapunzel" and was retelling it. The Grimms were aware of Schulz, mentioning him in their notes, but believed he was writing "undoubtedly from oral tradition." They do not seem to have been aware of the French tale at all. The most important change that the Grimms made was removing all sympathy from the fairy godmother's character. No longer was Rapunzel's tower a silver palace filled with delights; it was just a tower. They left out the ending with the reconciliation between Rapunzel and her godmother. Starting in 1819, as the Grimms edited the story with more descriptions and deleted ideas that were too French, they changed the fairy to a sorceress known as Frau Gothel. (Gothel is a German dialect word for "godmother.") Over later editions, she became an old witch. They edited her into something more similar to the ogress of the older Italian tale. They also toned down the story for children, removing references to unwed pregnancy. Rather than Rapunzel's pregnancy betraying her affair, she becomes dangerously stupid, blurting out that her godmother is much heavier than the prince. By the end she is mysteriously accompanied by her twin children, but nobody brings up pregnancy or scandalous unchaperoned visits. You can read D. L. Ashliman's comparison of the Grimms' first and final versions of Rapunzel here. Conclusion Rapunzel is a German author's translation of a French literary tale. Analyses should take into account how different Rapunzel is from its oral ancestors. I found it interesting that while the heroine's name can vary, the most common version by far is "Parsley." Perhaps elements of the La Force story did enter oral folklore. In their notes, the Grimms briefly mentioned a Rapunzel-like tale which began similarly to Bluebeard. A girl lived with a witch who gave her the keys but forbade her to enter one room. The girl peeked in anyway and saw the witch with two huge horns on her head. The angry witch locked the girl in a tower, accessible only by the girl's long hair, and the rest of the tale proceeded like Rapunzel. This version was summarized in their notes for The Lord Godfather (link in German). In some notes, this story seems to have become confused and attached to Friedrich Schulz’s Rapunzel, but I haven’t found any evidence that it appears in Schulz; his version of Rapunzel is identical to La Force’s Persinette. Personally, I was inspired to look into Persinette when I stumbled upon a claim on Tumblr that La Force's 17th-century story featured a heroine with psionic hair that she could use as extra arms or wings, and who was raised by a fairy named Gothelle. Frankly, this sounded ridiculously anachronistic. For one thing, "Gothelle" is just a faux-French spelling of the German word Gothel. Yet I found people reblogging it as if it was a fact. In truth, this description is from a modern retelling of Persinette in the webcomic "Emerald Blues." The fact that people latched onto it shows an element of wishful thinking. Modern readers want a more active heroine who could be a match for any fairy or witch. But in fact, there actually is an older Rapunzel who is an active heroine and a sorceress in her own right: Petrosinella. There's also the real Persinette, with its positive portrayal of female relationships, and a strict fairy godmother who is ultimately loving and benevolent. And there's the Persian heroine Rudaba, whose story sensibly points out over a thousand years ago that using someone's hair as a ladder might be painful. There are fairytales containing sexism and passive heroines, but just as often there are tales of brave, clever and magical women. Next time: some alternate endings to the Rapunzel story. Did you know that some versions keep going and become a gender-flipped version of Beauty and the Beast? SOURCES

Blog posts |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed