|

I'm excited to say that Writing in Margins made it onto Feedspot's Top 45 Fairy Tale Blogs!

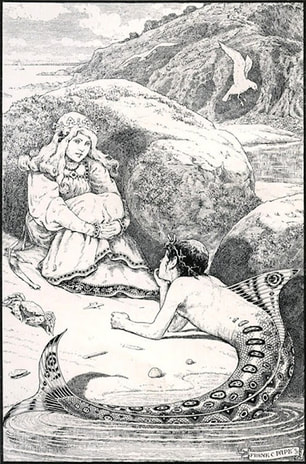

A while back, I discovered that an author named Ethel Reader had written a gender-swapped retelling of "The Little Mermaid" all the way back in 1909. Well, actually there are a lot of other elements mixed in. The story The novella begins by introducing the undersea kingdom of the Mer-People. In the kingdom is the Garden of the Red Flowers; a flower blooms and an ethereal, triumphant music plays whenever a Mer-Person gains a soul. The Little Merman, the main character, is drawn to the land from a young age. One day he meets a human Princess on the beach, and they quickly become friends. The Princess eventually explains that her kingdom is plagued by two dragons. She is an orphan, and the kingdom is ruled by her uncle, the Regent, until the day when a Prince will come to slay the dragons and marry her. The Little Merman wants increasingly to have legs and a soul like a human; there’s a sequence where he goes into town on crutches and ends up buying some soles (the shoe version). However, after some years, the Princess tries to take action about the dragons and protect her people. The Regent, who is actually a wicked and power-hungry magician, sends her away to school. The Little Merman asks her to marry him, but she explains that "I can't marry you without a soul, because I might lose mine" (p. 52). The Little Merman plays her a farewell song on the harp. The Little Merman talks to the Mer-Father, an old merman who explains that he once gained legs and went on land to marry a shepherdess whom he loved. However, when he made the mistake of revealing who he really was, the humans were terrified and drove him out. Unable to find a soul, he returned to the sea. The Mer-Father tells the Little Merman how to get to an underground cave, where he will meet a blacksmith who can give him legs. He gives him a coral token; as long as he keeps it with him, he can return to the sea and become a merman again. The Little Merman goes to the blacksmith, who happens to be a dwarf living under a mountain. He pays with gems from under the sea, and the blacksmith cuts off the Merman’s tail to replace it with human legs. The Little Merman wakes up on the beach, human and equipped with armor and weapons. The Mer-Father has also sent him a magical horse from the sea. He proceeds to the castle, where people assume he is one of the princes there to fight the dragon and compete for the Princess’s hand. The Princess, now eighteen years old, has just returned from college. The Princess doesn’t acknowledge the Little Merman—who is going by the name “the Sea-Prince”—and he’s afraid to identify himself after the Mer-Father’s story of being cast out. Every June 21st the Dragon of the Rocks appears and people try to appease it with offerings of treasure; every December 21st the same thing happens with the Dragon of the Lake. The princes go out to fight the Dragon of the Rocks, but it vanishes through a solid wall of the mountain; they all give up in disgust except for the Little Merman, who has been spending time with the Princess and now shares her righteous fury on her people’s behalf. With help from the dwarf blacksmith, he finds a way into the dragon's lair and slays it. The people adore him, while the resentful Regent spreads rumors against him, and the Little Merman is secretly disappointed that he hasn’t earned a soul. In December, the Little Merman goes out to fight the Dragon of the Lake. It drags him underwater, but he can still breathe underwater, and slays it too. The wedding is announced, but the Little Merman is conflicted; he still doesn’t have a soul, and if the Princess marries him, she will lose hers. He also fends off an assassination attempt from the Regent, but saves the Regent's life. The next morning, the Little Merman announces to the people that he is from the sea and has no soul. The Princess always knew it was him and loves him anyway, but everyone else rejects him and the Regent orders him thrown in prison. After a trial, he will be burned to death. The Princess gets the trial delayed and begins studying the royal library's law books. The Merman waits in jail, only to hear the Mer-People calling to him. They offer to break him out of jail with a tidal wave, but he refuses, worried about the humans. The Dwarf Blacksmith also offers him an escape, reminding him that he won’t get a soul either way; the Merman refuses again. Then the Little Merman's loyal human Squire visits. He has raised an army from the countryfolk, with the Sea-People and the Dwarfs also offering to fight. It may be bloody, but if they win, the Little Merman will have a chance to earn a soul. The Little Merman vehemently refuses; he will not kill his enemy, and he knows the kind of collateral damage that the Sea-People and the Dwarfs will bring to the kingdom. He gives the Squire his coral token, telling him to take it back to the Mer-Father; he is not returning to the sea. Alone in his cell, waiting for death, he hears the music that means a merperson has won a soul. The next day is the trial, where the Regent accuses the Little Merman of deception and treason. The Princess speaks up in his defense. The only issue is that the Little Merman doesn’t have a soul, so she reveals that she has found a record of a man from the Sea-People who came on land, was similarly accused of having no soul, and asked how he could get one. A local Wise Man told him that he would only win a soul when the Wise Man’s dry staff blossomed; at that moment, the staff put out flowers. The judge and lawyers decide to try this out, the Regent gleefully offers his staff, and the staff blossoms. The shocked Regent confesses all his crimes, including that he was the one who brought the dragons. The Little Merman intervenes to spare him from execution. The Little Merman and the Princess get married and rule the kingdom well, and there is a new red flower in the underwater garden. Background and Inspiration The Story of the Little Merman was initially released in 1907; it was a novella, with the same volume including an additional novella, The Story of the Queen of the Gnomes and the True Prince. Both were illustrated by Frank Cheyne Papé. The Story of the Little Merman was reprinted on its own in 1979. I have been unable to find much information about Ethel Reader, or any books by her other than this. In the dedication, she describes herself as the maiden aunt to a girl named Frances. The story itself has many literary allusions. It’s maybe twee at times but also had a lot of really funny lines. The overall mood made me think of George MacDonald’s writing. Some quotes that stuck with me:

First and most prominently, “The Story of the Little Merman” is an allusion to “The Little Mermaid.” Not only is the title similar, there is the description of the Garden of the Red Flowers, paralleling the Little Mermaid’s garden. There is also the overall plotline of the merman longing for both his human love and an immortal soul, going through a painful ordeal to become human, and winning a soul through self-sacrifice - with a final moral test where his loved ones beg him to save himself by sacrificing everything he's been fighting for. (One distinction: The Little Mermaid just gets the chance at an immortal soul, while the Little Merman actually gets his soul, along with a happily-ever-after with the Princess.) That's about where the similarities end. Reader’s book adds elements of dragon-slayer stories, and - most prominently - it plays on Matthew Arnold’s merman poems. “The Forsaken Merman” (1849) is one I recognized. Related to the Danish ballad of Agnete and the Merman, it tells of a merman who has taken a human wife and has children with her. The human woman hears the church bells and wishes to go back to land for Easter Mass: “I lose my poor soul, Merman! here with thee.” Once there, she never returns, leaving her husband and children forlorn. “The Neckan” (1853/1869) was new to me. This poem also deals with a human/sea-creature romance and the question of souls and religion. The Neckan takes a human wife, but she weeps that she does not have a Christian husband. So he goes on land, but when he introduces himself, humans fear and revile him. This is directly based on a Danish folktale, collected in Benjamin Thorpe's Northern Mythology: A priest riding one evening over a bridge, heard the most delightful tones of a stringed instrument, and, on looking round, saw a young man, naked to the waist, sitting on the surface of the water, with a red cap and yellow locks… He saw that it was the Neck, and in his zeal addressed him thus : “Why dost thou so joyously strike thy harp ? Sooner shall this dried cane that I hold in my hand grow green and flower, than thou shalt obtain salvation.” Thereupon the unhappy musician cast down his harp, and sat bitterly weeping on the water. The priest then turned his horse, and con tinued his course. But lo ! before he had ridden far, he observed that green shoots and leaves, mingled with most beautiful flowers, had sprung from his old staff. This seemed to him a sign from heaven… He therefore hastened back to the mournful Neck, showed him the green, flowery staff, and said : " Behold ! now my old staff is grown green and flowery like a young branch in a rose garden ; so likewise may hope bloom in the hearts of all created beings ; for their Redeemer liveth ! " Comforted by these words, the Neck again took his harp, the joyous tones of which resounded along the shore the whole livelong night (1851, p. 80) Arnold edited his poem after its first publication. In his first version, the priest rejects the Neckan and that’s it. In his second version, Arnold reintroduces the theme of the miraculous flowering staff. However, instead of being overjoyed like the Neck in the folktale, Arnold's Neckan continues to weep at the cruelty of human souls. The flowering staff is an old and widespread trope; it appears in the biblical story of Aaron, in a legend about St. Joseph, and most similarly in the medieval legend of Tannhauser, where a knight asks a priest if his soul can still be saved after he dallied in an underground fairy realm. While The Story of the Little Merman is clearly influenced by Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” it is equally or more inspired by “The Neckan,” even directly quoting it in one scene. I have never been a fan of the motif that merfolk don’t have souls, but it was an accepted idea in medieval legend. I recently read Poul Anderson’s The Merman’s Children, inspired by the story of Agnete and the Merman and thus distantly related to The Story of the Little Merman. In Anderson’s book, receiving souls is a Borg-like assimilation that costs the merfolk their old identities and memories. It’s a bitter take on the conflict between Christianity and paganism. Reader has a much more positive view on merfolk gaining souls. The merfolk are beautiful, but they just kind of exist, doing no harm and no good. They and other supernatural beings are part of nature. The Little Merman comes truly alive through his time on land, learning passion and emotions, and how to care about people other than himself. He learns how to feel anger and hatred, but these can be positive, the story explains—anger on behalf of vulnerable people, hatred of evil and greed. I like how the story raises the question of how the Merman actually acquired his soul. Did he earn a soul in the moment that he selflessly faced death and sent away his last chance of escape, or was his soul developing all along from the moment when he first saw land? The story hints pretty strongly that it’s the second one. I also really like the play on the Little Mermaid's final choice in Andersen's original. Here, this scene is greatly extended and really delves into the alternatives, raising different possibilities - might the Little Merman return to his old existence, or might he take a moral step back but then continue with his quest for a soul afterwards? He's not willing to do either. Whereas the Little Mermaid has to decide whether to harm her beloved who has hurt her deeply, the Little Merman is urged to kill a mortal enemy who has tried to murder him multiple times. He rejects this partly out of a sense of honor - he has killed dragons but he will not sink to the Regent's level by murdering a human - and partly because he foresees the bloodshed that this kind of war would bring to the whole kingdom. (In the illustrations, the Little Merman wears a crown - possibly of kelp - that looks a little like a crown of thorns.) It's also interesting to contrast the romance with that in The Little Mermaid. Here, the Merman and the Princess are childhood friends. They reconnect as young adults and their relationship deepens. The Merman is inspired by the Princess’s fierce love for her people. He does not have the Little Mermaid’s quest of marrying in order to get a soul; instead he is trying to get a soul so that he can marry the Princess. It’s his concern for her well-being that causes him to reveal his identity and give the chance for her to back out of their mandated engagement, even though it nearly costs him his life. The Little Merman has some fun fish-out-of-water moments and reads as a very peaceful, innocent character. There is a touch of realism in the fact that he gets beat up pretty badly in both dragon-battles and needs a lot of time to recover on both occasions. Meanwhile, the Princess is brave, loyal, and intelligent. She may not ride out to fight the dragons herself, but she’s the one who saves the Merman in the end, using her political savvy and education to delay his trial and build a legal defense. This book is chock-full of folkloric and literary references, and I think I might even prefer its take on souls to that of The Little Mermaid. Bibliography

0 Comments

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed