|

So after my last rather depressing post, I wanted to go in a lighter direction – namely, what was the original version of Tom Thumb like? Nobody really set out to collect English fairytales until after the Brothers Grimm got the bandwagon going in the 1800s. So we basically don’t have anything until very late in the game. Other countries tend to have several recorded variants of the Thumbling tale type. England has one very famous variant and that’s it. Naturally, I tried to go back to the earliest version, but even that is pretty confusing. The oldest surviving version of Tom Thumb, The History of Tom Thumbe, the Little, signed by R.I. (possibly Richard Johnson), was printed in 1621. However, it could be older, because the title page woodblock shows signs of wear (Opie, The Classic Fairy Tales, 30). One very big blank space that makes research problematic: none of these chapbooks include the date that the story was originally published. And that adds another wrinkle – which version came first? R.I.’s long prose version, which we know was in print at least by 1621? Or the metrical Tom Thumbe, His Life and Death, of which the earliest surviving print is from 1630? We don’t know when either was originally set to type! And there were probably others, long since lost.

Maybe there are contextual clues, though. R.I.’s version is a satire. It includes many elements that never appear in any other version – like magical gifts from the Fairy Queen, an encounter with the pygmy king, and a battle with the giant Garragantua (a common figure in pop culture at the time). The metrical version is much easier to find, and its verses are quoted even in modern retellings. So in the long run, it has been miles more popular. Perhaps R.I.’s version is based on the metrical version, or perhaps both are separate adaptations of the oral tale. R.I. also makes mention that this already is a very old and well-known story. I think it originated in an oral tale very similar to the thumblings of other countries, like the Grimms’ Daumling. Then someone, possibly R.I., added a section which was basically crossover fanfiction with King Arthur. R.I. refers to the character as “Little Tom of Wales,” so perhaps the story came from Wales – though before that, who knows. Tom Thumb is probably much younger than the tales of King Arthur, which have absolutely nothing resembling his story. ( King Arthur is in all Tom Thumb stories; Tom never appears in King Arthur stories.) Incidentally, however, Arthur originates in Welsh lore. If Tom Thumb truly did come from Wales, then that would be an interesting connection. So, what would the story have looked like before Arthur was added? It’s hard to say. There could have been a king whom Arthur replaced. The swallow cycle was probably in there in some form or other. But the story seems to have been so well-known that no one at the time ever thought to describe it – they could namedrop it and everyone would know what they were talking about. This is what happens in the earliest surviving mention is in 1579, in William Fulk’s Heskins Parleament Repealed, with the line "a little child like Tom Thumb." But in 1611, in Coryat’s Crudities by James Field, we finally get something more meaty: “Tom Thumbe is dumbe, untill the pudding creepe, in which he was intomb'd, then out doth peepe." In the fairytale, Tom is cooked into a pudding and has to break his way out, frightening a tinker in the process. We can know that even before 1621, one part of the story that definitely existed was Tom’s adventure with the pudding. In comparison, there is a story called Dathera Dad from Derbyshire, England. It’s usually grouped with Gingerbread Man variants, but it is near-identical to Tom’s adventure with the pudding and the tinker. Could this be evidence of a more widespread, forgotten English thumbling narrative? But Fielding might be referring to one of the print versions, not the oral version – remember, we don’t know the original publication dates! Ultimately, unless someone makes some groundbreaking new discovery, we can’t know anything for sure. Notes: There are a few books that reprint R.I.'s Tom Thumb. One is Merie Tales of the Mad Men of Gotam and The History of Tom Thumb, a version edited by Curt F. Buhler and put out by the Renaissance English Text Society. Another, available on Open Library, is The Classic Fairy Tales, by Iona and Peter Opie.

0 Comments

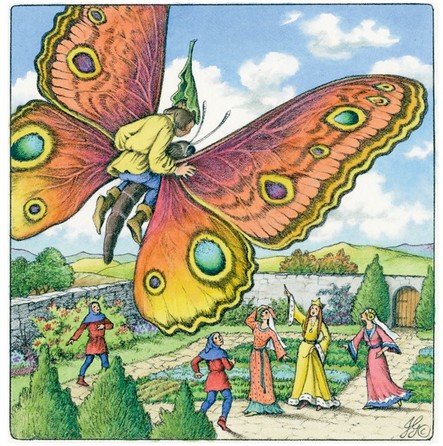

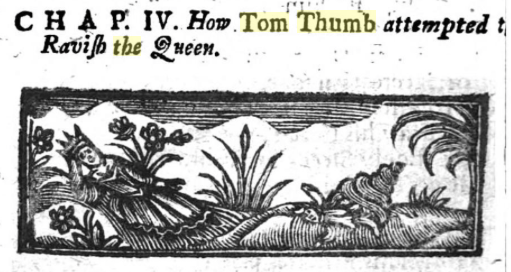

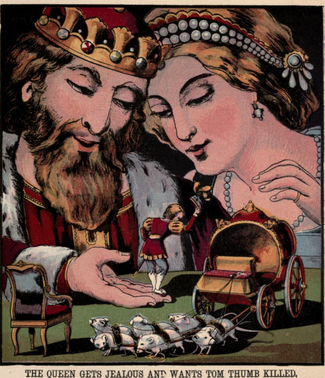

The following post deals with some mature subjects. Tom Thumb used to be a story for adults. The oldest surviving version was printed in 1621 and attributed to Richard Johnson; however, the one that has survived longest is its successor, a version in verse entitled Tom Thumbe, His Life and Death. This version trims down many of Johnson’s embellishments – it leaves out magical gifts from the Fairy Queen and a battle with Gargantua the giant. A childless man goes to Merlin, confiding his desire for an “heire, though it might be/ no bigger than his Thumbe.” Merlin obliges and in a matter of minutes, Tom is produced. There’s a joke about flatulence, and Tom is not only eaten whole by a cow but emitted out the other side “all besmeared,” and later is swallowed by a giant and vomited up. So this version is not exactly G-rated. Anyway, Tom makes his way to court, where he is greatly beloved by King Arthur, his queen, and all the knights and ladies. Tragically, he is exhausted by jousting, sickens and dies, and is greatly mourned. The end. Except that it wasn’t. Some time afterwards - like, 70 years afterwards - there were two new chapters printed. I am not sure when the new version came about, but according to James Orchard Halliwell (who reprinted it), it was written around 1700. I can find no record of the specific version, but there are scattered contemporary references to it. In 1711, in William Wagstaffe’s Comment upon the History of Tom Thumb, he mentions “That there has been publish'd Two Poems lately, Entitled, The Second and Third Parts of this Author, which treat of our little Hero's rising from the Dead in the Days of King Edgar.” There's a similar mention in the preface to the play "Tom Thumb the Great, or the Tragedy of Tragedies," in 1731. The identity of the author of the two "new" chapters is insignificant. I put new in quotes because most of it is simply the original repeated. However, they soon evolved into part of the Tom Thumb mythos, and brought with them a new, very dark element that for me casts a shade over the whole fairytale. First it reprints the entirety of “The Life and Death of Tom Thumb.” However, at the end, it is revealed that Tom didn’t die, but was taken by the Fairy Queen to her realm, where he would reign for two hundred years. He returns to the human world during the reign of King Edgar. (Edgar was a historical king, and these chapters may have contributed to a theory bopping around that Tom Thumb was based on his real-life court dwarf.) He makes his entrance by falling into the king’s firmity in the middle of a meal, offending the court in the process. (Firmity, or frumenty, is a kind of porridge and a popular medieval dish.) He is then swallowed by a miller and a salmon, in that order, before finally making peace with King Edgar and becoming a favorite of the court once more. While out hunting, he’s attacked by a cat and is so badly wounded that the Fairy Queen takes him to her realm once more. Now Part the Third begins, with Tom being returned to the human world once more. This time he falls into a close-stool pan, i.e. a chamber pot, which has apparently not been cleaned out. I’m questioning the Fairy Queen’s attachment to him at this point. The current king is Thunston. This name appears to have been made up entirely. Once recovered from his ordeal, Tom introduces himself, and Thunston thinks he’s the greatest thing ever. He makes Tom his page and showers him with gifts, including a coach drawn by six mice. However, Tom grows proud and ambitious, and begins to lust after Thunston’s queen. When the queen goes to rest in the garden and falls asleep, Tom spies on her from a snailshell and, in a very disturbing sequence, prepares to assault her. Though it's not explicit, you can tell what's happening. He may be tiny, but the scene is still deeply unsettling. She wakes up just in time and demands to know what he’s doing. Tom “made but a Jest, and laugh’d as he rose.” So he was in the act to the point where he has to stand back up, and he still laughs it off. The furious Queen now demands that he be executed. Not just punished, not banished; nothing suffices but that he die. Tom flees on a butterfly, but is captured and brought to trial. He makes a touching speech that wins over nearly all the Court, except of course the Queen “whom Rage and Fury did transport, no one could intervene.” Those dang women, getting mad when people try to rape them. Tom’s imprisoned in a mousetrap, where a cat finds him and accidentally breaks him out. Tom runs away, only to run into a spider’s web and be bitten. He dies of his injury, but his legacy lives on. Poor tragic little rapist Tom. Most commentators seem to have found these two chapters a poor addition to the story; however, many of the new elements stuck around in later retellings. These include Tom's return from fairyland, and his death via spider-bite That was around 1700. (Roundabout the same time this story was published, in the play Tragedy of Tragedies, Tom Thumb has an affair with King Arthur’s queen, here named Dollalolla.) But in the 1800s, Tom Thumb began to become a children's story. That meant a few things, like defecating cows and farting tinkers, needed to be removed or at least toned down. In many versions Tom became less of a trickster and more of a proper little man. And he had to be sympathetic. As a result of this facelift, the final conflict needed to change drastically. Around 1835, in “The Diverting History of Tom Thumb,” the queen plots to have Tom killed not because he's wronged her, but because he gets more attention than she does. Her motive changes from righteous fury to petty jealousy. The rape scene is gone. Tom is wholly innocent, and the queen is a villain. Dinah Maria Craik Mulock’s Fairy Book (1863), gives the trouble an even more specific cause - the tiny coach that Thunston gives to Tom. The queen, envious of this specific gift as well as the attention in general, “resolv[es] to ruin Tom” and tells the king that he was insolent to her. Her jealousy over the coach is also the catalyst in the 1880s' “Story of Tom Thumb” (published by McCoughlin Bros.) Here the queen is even worse - she weaves multiple lies and insists on Tom's torture in a mousetrap. Her complaint is always that Tom is disrespectful, but depending on how you read it, there may still be the implication that she's accusing him of rape. In at least some versions she uses the word "saucy," which can have erotic connotations.

Along with this change, there was another wrinkle. People started to simplify the stories, and the queen's identity changed. In Joseph Jacobs’ English Fairy Tales (1890) “The History of Tom Thumb" is near-identical to Mulock’s version, except that Thunston and his wife are replaced by Arthur and Guinevere. In The History of Tom Thumb by Helen and Bruce Gentry (1934) it’s also Arthur’s queen; the same in a 2010 retelling by Amy Friedman and Meredith Johnson. A far cry from the 1630 version, where Tom was a great favorite of Guinevere. For this reason, the story bothers me. The current villain of the tale has roots going back to a story where she is a victim of assault. By the hero. I don't know why the rape was added, but it was erased to make Tom look better and make the story more child-appropriate. Even before it was erased, it seems like the reader was still supposed to cheer for Tom and boo the queen. And making it more child-appropriate is ironic, because Tom Thumb is, at his core, a child. He is an infant who never really grows up. In other cultures the story ends with him returning to his home and the arms of his parents; in Tom's version, he tragically dies young. Some versions do have him become a man, take a wife, and become wealthy and successful. The three-part version has this happen, but in a twisted manner; instead of marrying and starting his own family, he is consumed by lust and it becomes his downfall. So all I can do is wonder a) who wrote this and b) why on earth they thought it was a good idea?! At two inches tall, life offers quite a few hazards. In medieval England, Tom Thumb’s most recognizable adventure was the time he got baked into a pudding. Fortunately, he popped out healthy as ever. Other characters, however, don’t have his lucky escapes. Drowning or burning seem to be the most common deaths in for Thumblings, but particularly drowning or burning in food.

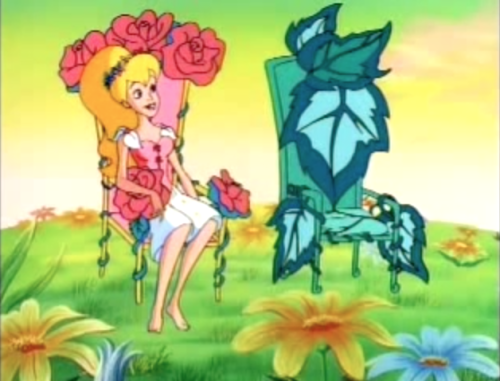

The Norwegian Tommeliten (Thumbikin) drowns in the smoroyet, or “butter eye” drizzled in the center of the porridge. On the same note, I recently came across two tales told by Norwegian storyteller Olav Eivindsson Austad. In both, a thumb-sized lad called simply Tume (Thumb) is accidentally killed by his mother. One suffocates in bread and the other drowns in buttered porridge. The buttered porridge incident in particular is probably a variant of Tommeliten. In a tale from Senovo, a character named Draganka drowns in a pot of beans. There are two variants in Bulgaria, one named Katsmatsura who is boiled up when she falls into a pot, and the other being an anthropomorphic rat. So why drown in food? None of these particular variants I’ve mentioned begin with food, but in fairytales, it’s very common for conception to be tied to the act of eating. A woman is told to eat a flower or a particular food to conceive. This is particularly true for thumbling tales. Some cut out pregnancy entirely and have the character created instantaneously from food – peas, gourds, or beans, usually chickpeas. A large number of oral thumbling tales begin with the woman wishing for a son while she’s cooking – the inciting incident is very often her stating her desire for a child to deliver his father’s lunch. The miraculous, instantaneous birth often then takes place in the kitchen. In a particular strain of the tale, a woman’s wish for children is answered with an impossible number of tiny chickpea children. Going instantly from wishing for a baby to being deluged with far too many hungry mouths to feed, she or her husband are driven to murder them. In some variants it seems to tie in with the idea of the parent finding their child boiled with the food - a very Hop o' My Thumb subject. There’s even a neat little list in the article “Catalogue Raisonn des Contes Grecs Types et Versions AT 700.” b: The mother (parent) kills them; by drowning them; b2: by throwing them into the pot; b3: by spraying with boiling water; b4: forcing them to return to the hole from which they came; b5: beating; b6: with a shovel; b7: the brush; b8: the basin of laundry; b9: the slipper; b10: other. Cheery subject. Back to the thumblings who meet a culinary doom. These usually seem to be cautionary tales – listen to your parents, don’t do foolish or dangerous things. The Bulgarian variants were probably a way to warn a child away from a hot fireplace. I’ve found quite a few reviews for The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but none for this little 1997 gem from Golden Films. I finally watched it, and it was surprisingly bearable. It opens with a song, led by Thumbelina flying around on a bird and making the flowers open up in the morning. Accompanied by animals and fairies, as well as a pig playing the piano (???), the song is a stirring piece that really speaks to the beauty of nature and the meaning of life. “Hi dum diddle dee, hi dum dee dum” (repeat 500x). They play the same shot of the animals jumping down a hill at least 3 times. This is not the last time they will reuse animation. That said, I immediately prefer the art style to that used in The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina in 2002. Thumbelina is an overworked ruler trying to keep the meadow organized while animals and fairies bicker. It reminds me a little of the Tinker Bell movies. There’s supposed to be a prince, but he was kidnapped when he was a baby (or not, we’ll get to that later). Mainly this just makes me wonder about Thumbelina’s backstory. She’s not a fairy, but they never say what she is. Her duties include dealing with three young delinquents with really annoying voices, and here we have our our kid appeal/comic relief team. Actually, I kind of grinned at some of the interactions here (“What makes you think it was fairies?” Cut to signed graffiti). The work’s getting to her, so she goes to ask advice from an old and inconsistently drawn tree named Oakley. In answer to her plea for advice, he decides to tell her her own backstory. Evidently, the Fairy Queen picked two children from noble families to reign as prince and princess of the meadow. And this just raises more questions. We still don’t know what Thumbelina is. And how did she pick these babies? What were their qualifications? So his advice on government is “wait for your prince to come and then live happily ever after.” I GUESS THAT SOLVES THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION. We cut to Tom Thumb, swinging from the curtains. He’s accompanied by a dog that resembles Max from the Little Mermaid, and does not talk. (Even though every single other animal seems to talk in this world, and humans have no trouble communicating with them. Are dogs the exception? Tom then flies around on a tiny motorcycle. I am not making this up. He heads into another room, where an Arthur-esque king and several knights are sitting around a round table. Gee, I wonder if the snobby guy with the nasal voice and the ugly pet bird could be evil. Turns out it’s the king’s son Mordred I mean Medwin, who wants to expand the Castle and open an IHOG (international house of gruel) at the expense of the Great Meadow. The king, however, values nature. Tom tries to give input, but they don’t hear him. He’s eating a snack in the kitchen, when the ugly bird (a raven named Edgar who says “Nevermore” all the time and sounds like a poor man’s Iago), corners a mouse. Tom runs over to defend her with a fork and they have a discussion about how he wants to be an important knight. He feels like he’s meant for more and pulls out a plot-relevant necklace and whoa, that matches Thumbelina’s necklace! What could this mean?!? Then they both get dumped into some batter by a cooking lady with a deep gravelly man’s voice. But it’s all good. Meanwhile, Medwin meets up with some thug and plots to kidnap the king. As usual, I’m baffled by how gleeful they are at the idea of being evil. Like, you can’t have subtlety in a cartoon. And if you were wondering when this film takes place, there’s an odd reference to the War of the Roses (”just like my father to fight over a bunch of flowers”). Thumbelina’s hiding in the bushes when suddenly the King comes riding along with Tom. Tom spots Thumbelina and they talk for a minute, when suddenly the King is kidnapped just offscreen. Tom races back to the castle and is ready to ride out to the rescue, but the knights tell him to stay put. Tom gets suspicious after Medwin and the bird, in public, at the top of their lungs, talk about getting things done their way now and cackle out hysterical evil laughter. Back in the meadow, the animals come running to tell Thumbelina about construction work ruining the meadow. She flies off on her bird to talk to the king. There’s a brief mention of taking away the teen delinquent fairies’ wings if they don’t shape up, which makes me wonder if Thumbelina is a wingless fairy. But she says at some point that Tom is not a fairy, implying that this isn’t the case. More on this later. She meets Medwin, and of course trying to persuade him to save the meadow doesn’t go well. She starts to leave on her bird. Tom’s swinging on curtains again (is this how he always gets around the castle?) and they crash into each other. She assumes Tom’s part of this construction project and gets mad at him. Tom doesn’t know what she’s ranting about, but then he overhears Medwin plotting. My notes at this point read simply, “Oh no,” because, without any preamble, there’s an abrupt cut to Medwin singing and dancing with construction workers and it’s the most bizarre, anachronistic piece of dinner theatre I’ve ever seen. They’re also reusing clips again. There’s also a mention of tearing down the meadow, which is confusing because it’s kind of flat. Tom Thumb arrives with Fiona in the now-fortified meadow. At first Thumbelina and the fairies think he’s a spy, but he explains the truth and lays out a plan to sabotage Medwin’s equipment. Thumbelina and the delinquents volunteer to help, and they all fly off. We cut to a party at night in the meadow. I guess they’ll do the sabotage later? “I think somebody spiked the nectar!” someone says in the background. WHAT? Romance incoming. Tom and Thumbelina start chatting, and mention that The writing is usually okay, aside from the songs, but there are some non sequiturs and oddly emphasized lines. “This might sound kinda weird but I feel kinda like I belong here.” “This may sound even weirder but I sort of feel the same way.” “I have some strange attachment to this meadow.” “Like, you know, like YOU belong here.” A song follows, and they declare their love for one another (that was quick), and … Whaaat’s he doing with his mouth? What follows is the most awkwardly animated kissing scene I’ve ever witnessed. On another note, Thumbelina’s outfit is weird. I thought those things on her shoulders were sleeves. They’re not. They’re just … sitting there, not attached to anything. We cut to Medwin hearing about the sabotage, and this is when I realize that the party was to celebrate the successful mission and we just skipped over the entire thing. Medwin plots to “catch flies with honey;” meanwhile Tom’s preparing to go back and stop Medwin once and for all. Medwin takes a frog hostage and plots to kidnap the fairies when they come to rescue. (I don’t think that’s what catching flies with honey means.) He tosses a turtle away when it tries to stop him, and it lands right in front of Thumbelina’s throne. Hearing the news, she and the delinquents rush off to save the frog. Medwin has completely immobilized the frog by tying his tongue to a piece of grass. (Wow, really?) However, in the process of freeing the trapped animal, Thumbelina and the fairies walk right onto a piece of flypaper. (I still don’t think that’s what catching flies with honey means.) Tom rescues them from Medwin’s birdcage. Medwin was monologuing as usual and mentioned where the king is being kept, so they go to search the dungeons. When they split up, Tom and Thumbelina make up a team and immediately find the king. Medwin has an army of Saxons coming in, so our heroes recruit all the fairies and animals to fight them off. Soldiers are reduced to running and screaming in terror by tiny creatures throwing nuts and water balloons. Oh, and there’s a skunk. And an angry bear. Actually, never mind, this is surprisingly effective, even though the delinquents still aren’t funny. They don’t hit a major roadblock until they realize that they can’t lift the key to the king’s cell. Anyway, it all works out. Tom gets knighted, but now his and Thumbelina’s duties must separate them. So sad. He decides to give her his necklace of plot relevance to remember him by. This summons the Fairy Queen! And it’s revealed that Tom is the long-lost prince of the meadow oh yes of course. Why can’t he remember his childhood? The narrator says he was a baby when he was kidnapped, but he looked like a young child, probably older than five. Anyway, Tom and Thumbelina can now be married and become king and queen (”that is, as long as it’s okay with you both,” the Queen says eloquently). And to reward the delinquents, she gives them new, better wings that look exactly like the old ones. Except all yellow. For his punishment, she shrinks Medwin and Edgar down to a tiny size and puts them in the model of the castle they were planning to build. And everyone lives happily ever after. There’s a weird mention of the two kingdoms becoming one, which doesn’t make much sense, as Thumbelina didn’t exactly make a marriage alliance with the king. So, a few notes. They never say what Tom and Thumbelina are, just that they’re from royal families and they are not fairies. We never see their parents, even in the flashbacks. It’s blurry, but the only people I can identify are a squirrel and a trio who seem to be the teen delinquents, the same age. The Fairy Queen displays the ability to shrink people, and fairies are known in real-world folklore as creatures who steal human babies and replace them with changelings. So my theory is that the Queen kidnapped two children from human royal families and shrunk them. She probably had good intentions, but she’s a fairy. Their morality doesn’t necessarily match up with ours in all the stories. As for animation: there are quite a few errors and reused footage, but what stood out to me was the inconsistencies in the tiny characters’ scale. In the first picture here, Thumbelina is smaller than a man’s eye. In the second, she’s about the size of a man’s foot. Not to mention this flawless bit with Medwin walking. And no, he’s not supposed to be shrinking in this scene. That little blue figure in the background is Tom.

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed