|

You may have heard of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but have you ever heard of Svend Tomling?

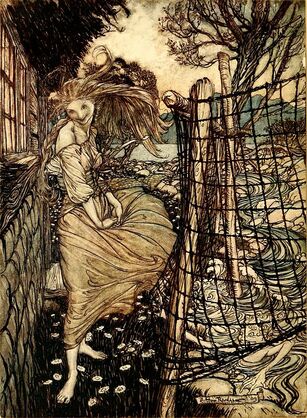

Svend Tomling is the third oldest surviving thumbling tale, and is largely forgotten other than a few footnotes. Interestingly, its more famous predecessors, the Japanese Issun-Boshi and English Tom Thumb, are both fairly unique among thumbling tales. Issun-Boshi is one of the short stories and fairytales known as the Otogizōshi, written down mostly in the Muromachi period from 1392-1573. The exact date of Issun-Boshi's origin is unclear, but it's usually assigned to the 15th or 16th century. Japanese thumbling tales make up a unique subtype, with similarities to The Frog Prince. "Issun-boshi" is a romance in which a tiny, unassuming hero wins a princess for his bride, and then transforms into a handsome prince. The story still contains classic Thumbling motifs, and the story is surprisingly close to that of Tom Thumb all the way over in England. Issun-Boshi is born to an elderly couple who pray for a son; he uses a needle for a sword; he leaves home to serve an important nobleman. An oni, or demon, tries to swallow him, but Issun-Boshi escapes from his mouth alive. Tom Thumb is also of unclear original date, but at least we have dates for some important pieces of evidence. His name is mentioned in literature as early as 1579. A prose telling of the tale was printed in 1621, and a version in verse in 1630, although these are dated to the printing of the individual copy, not to the date of composition. The prose and metrical versions are very different, but hit most of the same beats. A childless couple turns to the wizard Merlin for help. Their son, who is born unusually quickly and of tiny size, wields a needle for a sword. He is swallowed in a mouthful of grass by a grazing cow, cries out from its belly, and is excreted. A giant tries to devour him. He is swallowed by a fish and discovered when someone catches it to cook it. He goes on to serve in King Arthur's court, then falls sick. Here the two editions diverge - the metrical version has him die of his illness and be grieved by the court, but the prose version has him recover when treated by the Pygmy King's personal physician, and go on to have other adventures including fighting fellow literary character Garagantua. Both of these stories are clearly thumbling stories, but they do not fit the usual map of Aarne-Thompson Type 700, a formulaic tale found consistently through Europe, Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. The Grimms were aware of this formula and actually published two thumbling stories. Their first was Thumbling's Travels, also a rather unusual example, but they later went back and added Daumesdick (Thumbthick, also translated as Thumbling), which better fit the pattern. A childless couple wishes for a son; he is only a thumb tall; he drives the plow by riding in the horse's ear, is sold as an oddity, escapes, has an encounter with robbers, is swallowed by animals, and finally returns home. Issun-Boshi, again, is part of a unique subtype. As for Tom Thumb, it's likely the subject of some literary embellishment, expanding a simpler traditional tale. Hints of the wider tradition peek through, like a scene where Tom returns home with a single penny and is welcomed by his parents. This is where many Type 700 stories end, but Tom Thumb instead keeps going. The traditional tale started really getting attention with the Grimms, but they were not the first ones to publish an example. The earliest surviving specimen is the Danish "Svend Tomling", or Svend Thumbling. Svend is a common men's name meaning "young man" or "young warrior," giving it the same generic feel as "Tom" in English. Both Svend Tomling and Tom Thumb essentially boil down to the same name of "Man Thumb," the way the name Jack Frost boils down to "Man Frost." Svend Tomling appears to have been the generic name for a thumbling in Denmark; it was also used for a Hop o' My Thumb type, which is an entirely different tale. The relevant version is a 1776 booklet by Hans Holck. It drew attention from the Danish historian Rasmus Nyerup, and from the Brothers Grimm. Nyerup, in particular, remembered reading or hearing the story as a child. The translation I've been working on is admittedly choppy, and I take responsibility if it's in error. "Svend Tomling" begins, as most thumbling stories do, with a childless couple. The wife goes to visit an enchantress and, upon instruction, eats two flowers. She then gives birth to Svend Tomling, who is born already clothed and carrying a sword. The section that follows is almost exactly the classic thumbling tale, with some unique details. Svend helps out on the farm by driving the plow, sitting in the horse's ear. A wealthy man witnesses this, purchases him from his parents, and carries Svend away (specifically, keeping him in his snuffbox). Svend escapes. Falling off their wagon, he lands on a pig's back and begins riding it like a horse. However, he is attacked by wild animals, and eventually the pig runs away. Lost in the middle of nowhere, Svend overhears two men plotting to rob the local deacon's house and asks to come along. He makes so much noise that he awakens the servants, and the thieves flee. There is a small divergence here, where the house owners think that Svend is a nisse (a Danish house spirit similar to the brownie) and leave out porridge for him. It doesn't take long before Svend is accidentally swallowed by a cow eating her hay. He calls out from inside her stomach to the milkmaid, who is frightened and thinks the cow is bewitched. Here's another divergence: people take this to mean that the cow can foretell the future, and flood to visit. This introduces a long monologue from a priest complaining about the peasants. Ultimately the cow is slaughtered. A sow eats the stomach in which Svend is still trapped, then poops him out. He falls into the water, where his own father happens to hear him crying out for help, and takes him home to recover. So far the plotline has been generally typical, but at this point, the story strikes out in its own direction. Svend announces that he wishes to take a wife. In particular, he wants to marry a woman three ells and three quarters tall. The length of an ell varied by country, but in Denmark, it was considered 25 inches. Svend Tomling is speaking of a wife who would be something like seven feet tall. His parents try to dissuade him, saying that he's far too small, and Svend grows frustrated. He begins bothering a "Troldqvinden" (a troll woman or witch) until she gets angry and transforms him into a goat. His horrified parents beg her to have mercy, and she relents and changes him into a well-grown man. The rest of the booklet (four pages out of the whole sixteen!) deals with Svend and his parents discussing his future, with questions of choosing an occupation and a bride, as he sets off into the world. Rasmus Nyerup took a pretty dim view of this story, remarking that great liberties had been taken with the folktale he remembered - particularly the priest's long speech about the problems with peasants, which has nothing to do with Svend Tomling. I suspect that the disproportionately long section on life advice is also original. The motif of eating two flowers and then giving birth to an unusual child is striking. This is exactly what happens in the story of King Lindworm (also Danish), where the resulting child is a lindworm and must be disenchanted. Also in Tatterhood (Norwegian), the queen who eats two flowers gives birth to a daughter, just as precocious as Svend, who rides out of the womb on a goat and carrying a spoon. Tom Thumb is usually listed as an influence on Hans Christian Andersen's Thumbelina. However, I think Svend Tomling might have been a stronger influence. If Rasmus Nyerup heard the story as a child, Andersen might have too. Both Svend Tomling and Thumbelina begin with a childless woman visiting a witch for help. Svend's mother eating flowers to conceive hearkens to Thumbelina being born from a flower. Both Svend and Thumbelina focus on the question of the character finding a fitting mate and a society that they fit into. Svend, like Thumbelina, is faced with incompatible mates, although for him these are ordinary human women, and for her, talking animals. Ultimately, otherworldly intervention transforms them to fit into their preferred society. Svend goes to a troll woman who makes him tall enough to seek a bride, while Thumbelina marries a flower fairy prince and gains wings like his. (Actually, Issun-Boshi did this too, getting a magical hammer from an oni and growing to average height.) Overall, Thumbelina has more in common with Svend Tomling and even Issun-Boshi than she does with Tom Thumb. The story itself is not all that great, but it does provide one of our earliest examples of the Thumbling story - and casts light on the others that followed. Sources

1 Comment

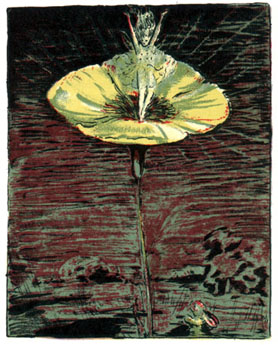

In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen published his fairytale “Tommelise,” or Thumbelina. A childless woman seeks help from a witch and receives a barleycorn. When planted, it grows into "a big, beautiful flower that looked just like a tulip" with "beautiful red and yellow petals." When it opens: "It was a tulip, sure enough, but in the middle of it, on a little green cushion, sat a tiny girl."

In "Thumbelina," Andersen took loose inspiration from older thumbling tales, but the heroine's birth from a flower is unusual. Some thumblings are created from a bean or other small object, but most often he or she is apparently born in the normal way, through pregnancy. Why did Andersen choose to write Thumbelina born from a flower - and what is the tulip's significance? Flower Fairies There's a widespread motif of fairies living in flowers. Andersen would have been well-aware of this trope. Thumbelina later encounters flower-angels (blomstens engels). They are evidently not quite the same species (winged and clear like glass, and dwelling in white flowers), but Thumbelina is happy enough to settle down with them. Another Andersen story, "The Rose Elf" (1839) also deals with tiny flower-dwelling spirits. The tiny flower fairy became popular around 1600. Shakespeare was an important influence; A Midsummer Night's Dream elves creep into acorn-cups to hide, and The Tempest's Ariel sings of lying inside a cowslip bell. In the anonymous play The Maid's Metamorphosis, a fairy sings of "leaping upon flowers' toppes". In the 1621 prose version of Tom Thumb, Tom falls asleep "upon the toppe of a Red Rose new blowne." In the 1627 poem Nymphidia, Queen Mab finds a "fair cowslip-flower" is a "fitting bower." What about older versions of the flower fairy? Greek mythology included dryads and other nature spirits, including the anthousai, or flower nymphs. Before Shakespeare, fairies in legends were generally child-sized at smallest - there are exceptions, such as the portunes of Gervase of Tilbury. Fairies, witches and other spirits were often said to ride in eggshells or crawl through keyholes. Fairies were held to live in nature and dance in "fairy circles" made of mushrooms or grass, or were encountered beneath trees. I'm also reminded of a 6th-century story recorded by Pope Gregory the Great, where a woman eats a lettuce which turns out to contain a demon. The demon complains, "I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." Superstitions held that demons might take up residence inside food if it wasn't properly blessed or protected with charms. Cowslips and foxgloves, already mentioned, were old fairy flowers. Cowslips are also known as fairy cups (Friend, Flower Lore), and foxgloves are fairy caps or as menyg ellyllon (goblin gloves). But these suggest very different scales. Flowers are hats and cups in language, but houses in literature. Katharine Briggs argued that Shakespeare did not originate the tiny flower fairy, but was inspired by contemporary tradition - however, there's not much evidence for this. Diane Purkiss took the exact opposite point of view, deeming it "questionable whether Shakespeare knew anything about fairies from oral sources at all," but I think this is an unnecessary leap. In more of a middle ground, Farah Karim-Cooper suggested that Shakespeare actually rescued fairies. In contemporary culture, they were being demonized, grouped with devils and witches and sorcery. Shakespeare made them benevolent but also tiny, therefore harmless and acceptable. In 1827, Blackwood's Magazine talked about Shakespeare's fairies and how they would "lodge in flower-cups, a hare-bell being a palace, a primrose a hall, an anemone a hut." I do not recall seeing these specific examples in Shakespeare, but this was now the popular perception. In the first 1828 edition of The Fairy Mythology, Thomas Keightley also talked about "the bells of flowers" as fairy habitations. "Oberon's Henchman; or the Legend of the Three Sisters," by M. G. Lewis (1803) describes fairies "Close hid in heather bells". In the poem “Song of the Fairies,” by Thomas Miller (1832), the fairies "sleep . . . in bright heath bells blue, From whence the bees their treasure drew," and then just in case we missed it, their "homes are hid in bells of flowers." Later in the same volume, a fairy named Violet "in a blue bell slept." Hartley Coleridge wrote of "Fays That sweetly nestle in the foxglove bells” (Poems, 1833) and Henry Gardner Adams had "The Elves that sleep in the Cowslip’s bell" (Flowers, 1844). The wood anemone was another fairy flower; at night the blossoms curled over like a tent, and "This was supposed to be the work of the fairies, who nestled inside the tent, and carefully pulled the curtains around them." (The Everyday Book of Natural History, 1866) This implies the existence of another explanatory legend. In a paper presented at a meeting of the New Jersey State Horticultural Society - yes - and published in 1881, the writer reminisced "I remember how I enjoyed the imaginary exploits of the little fairies that had their homes in these flowers. I had always thought it a pretty conceit to make the fairies live in flowers, but never thought how near the truth it is" . . . And then comes a leap to microorganisms. "A flower is a little universe with millions of inhabitants." Children's literature at the time was focused on edifying, providing morals, and providing scientific education. Fairy stories were considered a natural interest for children, and so they were often used to dress up school lessons, particularly on the natural world. They were a perfect way to launch into a lesson on insects or the world that could be found through a microscope. What about tulips specifically? David Lester Richardson's Flowers and Flower-Gardens (1855) mentions that "The Tulip is not endeared to us by many poetical associations." On the other hand, writing a century later, Katharine Briggs believed that the tulip was "a fairy flower according to folk tradition" and that it was a bad omen to cut or sell them. Taking a step back: in European thought, after the crash of the Dutch "tulip mania" in the 1630s, tulips generally became symbols of gaudiness and tastelessness, particularly in superficial female beauty - for instance, Abraham Cowley in 1656 writing "Thou Tulip, who thy stock in paint dost waste, Neither for Physick good, nor Smell, nor Taste." (Rees). As time passed, this faded into the background, but was not forgotten. David Lester Richardson wrote that tulips had remained extravagantly expensive, even in England, as late as 1836. There are a couple of 18th-century examples of tulip fairies. Thomas Tickell's poem "Kensington Garden" (1722) speaks of the fairies resembling a "moving Tulip-bed" and taking shelter in "a lofty Tulip's ample shade." In 1794, Thomas Blake's poem "Europe: A Prophecy" described a fairy seated "on a streak'd Tulip," singing of the pleasures of life. Intriguingly, in the same decade as Thumbelina, an early English folklorist named Anna Eliza Bray collected a story which also featured fairies within tulips. She recorded it in 1832 and published it in 1836, in A Description of the Part of Devonshire Bordering on the Tamar and the Tavy. The story follows an elderly gardener who discovers that the pixies have begun using her tulilps as cradles for her babies. She eventually dies. Her heirs rip up the flowerbed to plant parsley, but find that none of their vegetables will grow there. Meanwhile, the gardener's grave always mysteriously blooms with flowers. Bray does not give a specific source, other than to speak briefly of gathering the tales from village gossips and storytellers, with the assistance of her servant Mary Colling. Bray's pixie story was retold in fairytale collections and books of plant folklore. When she published a children's book, A Peep at the Pixies (1854), most of her focus in the introduction was on pixies’ small size relative to children; they could "creep through key-holes, and get into the bells of flowers." By the 20th century, the tulip as fairy flower was set. James Barrie wrote in The Little White Bird (1920) that white tulips are "fairy-cradles" (158), and Fifty Fairy Flower Legends by Caroline Silver June (1924), reveals that “Fairy cradles, fairy cradles, Are the Tulips red and white." Folklore In fact, fairies were not the only denizens of plants in legend. Birth from plants is very common in fairytales. English children were told that babies might be found in parsley beds, while in Germany, infants were more likely to be found among the cabbages or inside a hollow tree. (Curiosities of Indo-European Tradition and Folklore) In a French version, baby boys were found inside cabbages, baby girls inside roses. (e.g. Revue de Belgique, 1892, p. 227) Gooseberry bushes were also a likely spot. In Hindu culture and mythology, saying someone was born from a lotus was a way to indicate their purity. In Japanese stories, baby Momotaro is found inside a peach, and Princess Kaguya inside a bamboo. The Indian tale "Princess Aubergine" has a girl born from an eggplant. In the Kathāsaritsāgara (Ocean of the Streams of Stories), an 11th-century collection of Indian legends, Vinayavati is a heavenly maiden (divyā-kanyakā) who is born from the fruit of a jambu flower after a goddess in bee-form sheds a tear on it. In the Italian tale of "The Myrtle", from the Pentamerone (1634-1636), a woman gives birth to a sprig of myrtle. A fairy (fata) emerges from the plant each night, and a prince falls in love with her. However, the heroine is apparently of human scale, although she inhabits a plant not unlike a genie in a lamp. Later folklorist Italo Calvino collected more variants: "Rosemary" and "Apple Girl." The woman or fairy hidden within a luscious fruit appears in tale types such as "The Three Citrons." With the first known example of this story in The Pentamerone, there are probably as many variants of this story as there are types of fruit. In a close fairytale neighbor, a mother eats a flower to become pregnant - see the Norwegian "Tatterhood," the Danish "King Lindworm," and "Svend Tomling." "Tom Thumb" is usually cited as an influence on Thumbelina; in this story, a childless woman consults Merlin for help. Merlin prophesies her child's fate, she undergoes a very brief pregnancy, and then gives birth to a child one thumb tall. However, the two stories have little in common; the Thumbling tale type is widespread, and Andersen may have been inspired by other examples. The most likely candidate is "Svend Tomling," a chapbook written by Hans Holck and published in 1776. My translation is very choppy, but I think the gist is that a childless woman consults a witch. The witch causes two flowers to grow and instructs the woman to eat them. The woman then gives birth to Svend, one thumb high and already fully dressed and carrying a sword (beating out Tom Thumb, who has to wait several seconds for his wardrobe). I don't know for sure if Andersen knew this story, which hasn't achieved quite the same ubiquity as Tom Thumb. However, the fact that it was from his own country, and the similarities in Svend Tomling's and Tommelise's births, make a relationship seem likely. E. T. A. Hoffmann Fairytales weren't Andersen's only inspiration. One of his major influences was the fantasy/horror author E. T. A. Hoffmann (creator of The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, among other things). In Hoffmann’s “Princess Brambilla” (1820), a fairytale-esque subplot has the magician Hermod tasked with finding a new ruler for the kingdom. He causes a lotus to grow, and within its petals sleeps the baby Princess Mystilis. The person-inside-flower motif recurs throughout the story. Mystilis is later placed in the lotus to break a curse that has fallen on her, and emerges the second time as a giantess. Hermod himself is frequently seen seated inside a golden tulip. “Master Flea” (1822) has similar imagery. A scholar, studying a "beautiful lilac and yellow tulip," notices a speck inside the calyx. Under a magnifying glass, this speck turns out to be Princess Gamaheh, missing daughter of the Flower Queen, now microscopic and fast asleep in the pollen. Conclusion Andersen created his own thumbling tale inspired by folktales like that of Svend Tomling. However, he wove in plenty of elements in his own way - such as talking animals, or a girl born from a tulip. His work, including both "Thumbelina" and "The Rose-elf," shows the contemporary interest in fairies who lived inside flowers. Andersen's fairies in particular are most like personifications of plants. In the past, tulips had gained a bad reputation, becoming symbols of shallow frippery. However, by the time Andersen wrote, the disastrous tulip fad had had time to fade into history a little more. Instead, tulips started to be mentioned occasionally with fairies. In the 1800s, one author might have noted tales of tulip fairies as rare. However, a century later, Katharine Briggs could categorize it as a fairy flower. What changed? The most important thing may have been new associations for the tulip's shape; it was grouped in with other flowers that resembled bells or cups. I was startled when I went looking for examples of flower fairies - I occasionally found descriptions of them resting on top of the flowers, like Tom Thumb. However, more often than anything, I found the word "bell." Heather-bells, foxglove-bells, cowslip-bells, bluebells, bell-shaped flowers. In 1832, Thomas Miller's flower-fairy poem used the word bell three separate times. With fairies increasingly shrunken around Shakespeare's time, flowers that would have once been cups or hats were instead envisioned as houses or hiding places for fairies. The shape does suggest that something could be tucked inside, and lends itself to an air of mystery. Storytellers, including Andersen, focused on the idea of the hidden observer. Mary Botham Howitt wrote in 1852 "We could ourselves almost adopt the legend, and turning the leaves aside expect to meet the glance of tiny eyes." (George MacDonald used similar images, although with a more sinister slant, in his 1858 book Phantastes.) However, although Thumbelina's birth is still tied to the idea of flower fairies, it has more in common with tales of heroes born from plants. It is also strikingly reminiscent of E. T. A. Hoffmann's short stories; Hoffmann wrote twice of tiny princesses discovered inside flowers. In his work, tulips were not just gaudy or overly expensive, but had esoteric and mystical associations. His characters may be Thumbelina's clearest literary ancestors. Further Reading

Ruth Tongue had an unusual approach to folktale collecting. By her own account and those of others who knew her, she generally collected her stories by remembering them from her early childhood or throughout her life. She was in many ways her own source. And her stories are unique. Beyond their distinctive tone, there are colorful fairies and monsters that are distinct from other collected folklore. As Bob and Jacqueline Patten wrote of Tongue's creatures, "Nowhere else are found the Apple Tree Man, the Conger King, The-One-With-The-White-Hand, Boneless, or Meet-on-the-Road."

Maybe she did make up the Conger King or Meet-on-the-Road. But after research, I believe that Tongue did not make up quite so many of her unique creatures as some have suggested. For instance, Boneless had appeared previously, listed among other monsters by Reginald Scot and, later, Michael Denham - although it received no description and remained mysterious. Tongue, however, published a story in which the Boneless was a kind of blob creature. She also published wholly unique stories explaining the Boneless' fellow bogeys, the Galley-beggar and the Bull-Beggar. I believe that a number of Tongue's other creatures had similar histories - she did not make them up out of whole cloth. Instead, she borrowed ideas from scholars and fiction authors. Tongue used not only folklore collections but fantasy books to bolster her credibility as a folklorist. Actually, it makes sense. Although she made much of her connection to Somerset, most of her formative years were spent elsewhere. She was clearly well-read. In Forgotten Folk Tales, (p. 32), she mentioned James Fraser's Golden Bough, tying her stories into his worldview of comparative folklore. The famous Katharine Briggs was Tongue's mentor and frequently relied on her as a source. Briggs categorized many of Tongue's stories and found parallels in other collections. Of Tongue's story "The Sea-morgan's Baby," in which a childless couple adopts a merbaby, Briggs wrote that it "suggests the tale given literary expression in Fouque's 'Undine.'" (xv) The 19th-century novella "Undine" was, of course, influenced by folklore - the myth of the watery fairy bride. But Briggs' method puts forward the case that there was also an older legend of a human couple raising a merchild, which led to both "Undine" and Ruth's "Sea-Morgan" story. It discounts the possibility that "Undine" itself influenced folklore. It also discounts a pertinent question - did Ruth really find the folktale that lay behind Undine, or was she inspired by Undine? Similarly, in Folktales of England, Briggs compared Tongue's "The Sea Morgan and the Conger Eels" to the Odyssey and to Rudyard Kipling's story "Dymchurch Flit." She had comparisons and supporting evidence for all of the tales; "The Hunted Soul" was "almost identical" to a story told by Anna Eliza Bray in The Borders of the Tamar and the Tavy (vol. 2, p. 114). Tongue picked this up and made similar cases. One example was her story "The Danish Camp," in which redheaded Danish invaders kidnapped English brides. One night, in the midst of their revels, the women rebelled and slew them all, with the exception of a single boy whose lonely song still rings through the hills. In the notes of Somerset Folklore, Tongue wrote, “Wordsworth remembers him in a poem.” She showed her literary expertise and the older existence of the tale. Or at least, she tried to. Wordsworth's fragmentary poem "The Danish Boy," first published in the second edition of Lyrical Ballads (1800), does bear a surface similarity to Tongue's story . . . insofar as it mentions a Danish boy. In fact, Wordsworth wrote in his letters that the poem was "entirely a fancy." He wrote further: "These Stanzas were designed to introduce a Ballad upon the Story of a Danish Prince who had fled from Battle, and, for the sake of the valuables about him, was murdered by the Inhabitant of a Cottage in which he had taken refuge. The House fell under a curse, and the Spirit of the Youth, it was believed, haunted the Valley where the crime had been committed." It seems that Ruth found the wrong Danish Boy. Wordsworth was not inspired by a legend of a Danish camp in England. He was creating a unique ghost story about a prince murdered for his wealth. However, there is evidence for the story of "The Danish Camp" existing before Tongue, at least in fragments. In her early work, such as Somerset Folklore (1965), Tongue's stories fit into established tale types. You could find other books telling the same stories. They showed her signature spark of storytelling, but they were also familiar, as would be expected for traditional folktales. But were they too familiar? One book that Tongue drew on and cited often was Tales of the Blackdown Borderland by F. W. Mathews (1923). Was she just citing it for textual support, or something more? According to Jeremy Harte, it was something more: Ruth "rescued" at least fifteen tales from this small book "and reattributed them to her childhood encounters." Tales which appear in both Mathews and Tongue include "The Fairy Market," "Blue-Burchies," the tale of Jacob Stone, the Hangman's Stone, "The Sheep-Stealers of the Blackdown Hills," the ghost story of Sir John Popham, "Gatchell's Devil," and "Robin Hood's Butts." Plotlines were identical right down to locations mentioned. Somerset Folklore also relied on “Local Traditions of the Quantocks” by C. W. Whistler, a 1908 article in Folklore. Stories which coincide are "Stoke Curcy," the tradition of hunting Judas, a tale of helpful pixies threshing wheat, “the blacksmith who shod the devil’s horse,” "The Devil of Cheddar Gorge," "The Broken Ped," "The Gurt Wurm of Shervage Wood," and the basic elements of "The Danish Camp." Tongue's stories followed the same patterns as their predecessors, but tended to be "more engagingly told," as J. B. Smith put it. Her versions had more dialogue, smoother plot arcs, and her own signature style. J. B. Smith pointed out that Tongue's story "The Croydon Devil Claims His Own" was also very similar to an older tale, "The Devil of Croyden Hill," published in the magazine Echoes of Exmoor in 1925. True, that is to be expected - but Smith listed multiple variants of the tale, each with their unique plot points. Tongue's was unique in that it wasn't unique. Smith wrote that Tongue's version, unlike the others, "shows every sign of being a retelling of (C1), down to small details of topography. It also stands out from other tales in her Somerset Folklore in being unattributed, a fact hardly calculated to allay suspicions that it is an adaptation of (C1) rather than a tradition in the true sense." There are some distinct Tongue-isms, such as the villain being a redhead, and the unusually supernatural ending (most of the stories have a skeptical theme). So these stories are well-known folktales from legitimate story families, but sometimes the details are so close to other people's renditions that it becomes noteworthy. It has led J. B. Smith to suggest that these stories are prototypes and not parallels; Jeremy Harte to say that Ruth took "over ten out of the fifteen or so narratives in [Whistler's article], and refashioned them." It was in Forgotten Folk Tales of the English Counties, Tongue's 1970 book, where she really branched out. These stories are strikingly unique not just in style but in plot. The whole basis of the collection was that these were tales that had escaped every other collector, and were only unearthed by Tongue. Tongue seemed endlessly capable of finding a folktale to match any saying or term. "Lazy Lawrence," an old character and personifying term for laziness, showed up as the name of an orchard-guarding fairy horse. "The Grey Mare is the Better Horse," a saying about henpecked husbands, showed up as a Robin Hood tale (in which all of the wives are quite meek and docile, by the way). "Tom Tiddler's Ground," a children's game, showed up as a story about hidden fairy gold. Hyter Sprites, an obscure type of spirit, were not much known beyond their name existing in a few dictionaries - but Ruth provided a whole story of their antics and their ability to transform into birds. There are a few stories that I think deserve special attention here. "The Grig's Red Cap" This is one of the few times in which I believe Ruth catches herself in a direct lie. In 1864, an editor of Transactions of the Philological Society theorized that a grig might be a fairy name, based on the word "griggling," a term for collecting leftover apples. After all, similar terms were "colepexying" and "pixy-hoarding." A hundred years later, in Somerset Folklore, Ruth made the same case thinking along the same lines. As evidence, she also added in the story of "Skillywiddens," where the fairy is nicknamed Bobby Griglans. Tongue wrote that "It seems a reasonable inference that the grig is fairy of sorts [sic].” In fact, the etymology is not as clear as it might seem. "Griggling" is most likely derived from "griggle," a word for a little apple. "Griglans" means "heather." But a few years after that, in Forgotten Folk Tales, she gave the story "The Grig's Red Cap," on page 76, and notes "Heard from old Harry White, a groom at Stanmore, 1936. Also from the Welsh marshes, 1912." This implies strongly that Ruth is the one who heard the tale in 1912 and 1936 . . . despite seeming to guess at the grigs' very existence in 1965. Was Ruth inspired by that old journal issue? Did she decide that grigs deserved their own story - even if she had to construct it herself? The Asrai The asrai was a water fairy who emerged from her lake on moonlit nights. A greedy fisherman kidnapped her, planning to sell her, but the delicate sprite could not bear sunlight. At dawn, she melted into a puddle of water -- while the fisherman would always bear her freezing cold handprint on his arm. Katharine Briggs noted in The Fairies in Tradition and Literature that "The name is mentioned in Robert Buchanan's verses." Robert Buchanan actually wrote two poems about the asrai, although the plots bear no resemblance to Tongue's tale. Although Buchanan clearly took inspiration from folklore, the asrai seem to be his own creation. He is the only person ever to mention them until Ruth Tongue, and he developed their characteristics between poems. His asrai are pale beings who avoid sunlight – metaphorically melting away when the sun emerged and humanity became the dominant species. Tongue’s asrai are much more fishy in appearance, and literally melt if they encounter sunlight. Tongue may have even subtly woven in a little etymology, saying that one person thought an asrai was a newt. Asgill is an English dialect word for newt. The "asrai" name was not from folklore - but still, perhaps the plot was. There are plenty of English stories of fishermen encountering or netting mermaids. Closer still, the French "Dame de Font-Chancela" was a fairy who appeared on moonlit nights by a fountain. A lustful nobleman tried to carry her away on his horse, but she vanished from his arms just as if she’d melted, and left him with a frozen feeling that prevented any further escapades for some time. (You go, girl.) I don't know if Tongue read French, but the story was cited in various French books and could very possibly have made its way to England. "The Vixen and the Oakmen" In this tale, a fox is protected by the Oakmen, dwarfish forest guardians who live within the great oak. Other characters include a helpful talking hawthorn tree and a malicious, murderous holly. In her notes, Tongue drew connections to two fiction authors. "For other references, see Beatrix Potter, The Fairy Caravan... J. R. R. Tolkien makes dynamic use of similar beliefs in The Lord of the Rings" (18). Again, Katharine Briggs happily put forward Beatrix Potter's books as evidence of tradition. She wrote in Dictionary of Fairies (1976) that "It is probable that [Potter's] Oakmen are founded on genuine traditions," and in The Vanishing People (1978), "Although [The Fairy Caravan] makes no claim to be authoritative the legend is confirmed by the collections of Ruth Tongue." Major, major problem here - Potter was not inspired by folklore, but by her niece's imaginary friends, and she was blocked from writing more about them by copyright concerns, because her niece had gotten them from a book. The most likely candidate for the infringed-upon book would be William Canton’s works. In fact, Tongue included all of William Canton's oak-men books in her bibliography for Forgotten Folk-Tales, although she did not explain the connection. Briggs seems to have been unaware of Canton, or she would certainly have included him as "proof" of oakmen's traditional nature. Beatrix Potter's behavior undermines the idea that the oakmen could be traditional. But Tongue would not have known any of this. Only later was the full story published in Leslie Linder's History of the Writings of Beatrix Potter. In addition, The Fairy Caravan's oakmen are seen around "the Great Oak" and care for animals. It's important to note that this book featured many local landmarks from the Lake District, where Potter lived. The Great Oak was "the great oak beside the road going to Lakeside, beyond Graythwaite Hall." (Linder p. 302) Tongue attributes "The Vixen" to the Lake District, and she also wrote of the Oakmen living within "the great oak." Tongue doesn't just give oakmen a similar role to those of Potter. She uses the exact same phrase for their dwelling place, even if it is stripped of context. As for Tolkien, he did not write about oakmen, but he did, of course, have many sentient or moving tree characters. A sentient willow tries to kill people in Tolkien's Fellowship of the Ring, and Tongue wrote that "The Barren Holly is credited, like the Willow, with being a murdering tree". "The Wonderful Wood" Oak trees are friendly to a mistreated girl. An evil king and army pursue her through the woods, but wind up mysteriously vanishing: "For the trees closed about and they never got out/ Of the wood, the wonderful wood." Says Ruth: "Trees are believed to be very revengeful and murderous at times. See B. Potter, The Fairy Caravan... J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Pt 3, p. 19." The reference to Beatrix Potter is probably the "Pringle Wood" that features in The Fairy Caravan: an ominous oak forest, home to unseen, malevolent beings, which can only be navigated when magical protections are in place. (Also based on a real location, as it happens!) The Tolkien reference is to The Two Towers and the Battle of Helm's Deep, where Saruman's fleeing army encounters the forest of sentient trees or "Huorns." "Like a black smoke driven by a mounting wind... [the Orcs] fled. Wailing they passed under the waiting shadow of the trees; and from that shadow none ever came again." "In My Pocket" A clever dwarf hides in a giant's pocket. He helps the giant solve a wizard's riddles so that they can win the wizard's sheep and escape imprisonment. The final riddle which stumps the wizard: "'Two for one' (and that was the giant), 'A small one for the rest' (and that was the brothers), 'And a little, little piece for my pocket' (and that was the good little dwarf)." Says Ruth: "It is likely that this Norse tale did not come from a chapbook, but existed as oral tradition only. Perhaps Professor Tolkien came across a variant (see J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit). It might be traceable." She is suggesting that Bilbo Baggins' famous riddling contest with Gollum, which ends with the trick question "What is in my pocket?" was inspired by her folktale. Conclusion Forgotten Folk Tales was written at the apex of Tongue's fame, and was the book where she showed her hand the most. She didn't just write about obscure creatures; she wrote about creatures which had only ever appeared in fantasy works. Her previously collected folktales could be near-identical to those collected in other books. That was not so unusual. Indeed, it served as proof, footprints showing where and when else the stories had been recorded. Her sources could be vague enough to leave it unclear whether she had actually heard them herself, and no one would strongly challenge her. I think that in 1970, she got cocky. Encouraged by Briggs, she decided that this applied not only to obscure folktale collections, but to fantasy writers. Whistler and Mathews and William Wordsworth were evidence that her stories were old and established. In the same way, Robert Buchanan, Beatrix Potter, and J. R. R. Tolkien could be evidence! Even when the similarities were much vaguer, they still showed that she had not made up these stories and that others really had "heard" them. In this backwards way, Tongue recast authors' original work as folktale collections. She denied them their creativity as authors. And Briggs ate it up, and so apparently did others. A few reviews might have mildly pointed out that Tongue's sources were a little confusing, but it was not until after her death that people actually began to voice their doubts. Sources

Other blog posts |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed