|

First I have to thank the lovely Kristin from Tales of Faerie for hosting my guest post on her blog. She writes about a lot of different fairytales and it's a great read. This is kind of weird, because I've done so much research on thumbling tales, but my favorite fairytale is actually Tatterhood. There is a comic adaptation that I heartily recommend, and a very funny analysis by Ursula Vernon. To make a long story short: a queen longs to have a child, and eventually meets a wise woman who tells her to grow a magical flower and eat it. However, she is not to eat the weed that grows with it. Predictably, the queen eats the weed and gives birth to two daughters. One is the classic beautiful princess, and the other - Tatterhood - is unkempt and noisy. She comes out of the womb riding a goat and waving a spoon. I'd pay good money to see an adaptation where someone actually goes into the implications of a woman giving birth to two girls, a goat, and a spoon. The two sisters are the best of friends, but when trolls attack and Tatterhood is busy fending them off with her battle spoon, a troll steals the beautiful princess's head and replaces it with a cow's. Cue an adventure to retrieve the right head. At the end, the sisters marry a king and a prince, respectively, and Tatterhood reveals her . . . magic powers? There are so many questions raised by this story. There's even an adopted princess running around who's only mentioned in the prologue of the story. Seriously, what happened to her? This post is kind of a counterpart to the theme of death and food, as well as building off Nang Ut and the Miraculous Birth. Here we have life and food! Like Tatterhood, many, many fairytales begin with infertility, and in many, many fairytales a woman is able to have a child after, say, an old beggar gives her something to eat. This is Aarne-Thompson Motif T511 and comes with a whole host of variations - eating fruit, flowers, fish, you name it. In Tatterhood, the queen eats a rose and a weed. In Prince Lindworm, the queen eats a pair of roses. In the Snow Daughter and the Fire Son, a woman swallows an icicle and a spark. (That one ended badly, but I like the first half of the story.) In Ivan the Cow's Son, the fateful meal is a fish (which is eaten by a queen, a servant, and a cow, who all bear identical sons - this story raises all kinds of questions.) Food is often a symbol for desire or temptation. In some, like Nang Ut, the food is the means of contact between the mother and father. However, in many instances of T511, the father almost seems like a sidenote. The mother wants a child and she gets one with or without him, often through the intervention of another female character like the beggar woman in Tatterhood. Some versions skip the pregnancy and have a child directly born from a fruit or flower - like Thumbelina, who has no father figure whatsoever. On a slightly different twist, sometimes the food is a means of rebirth In Welsh myth, Gwion flees Cerridwen in a transformation sequence, finally becoming a grain of wheat, which she devours. This causes her to become pregnant and give birth to him as her son, Taliesin. In a Cahto Indian tale from California, as part of a Prometheus-style ploy to win light, Raven becomes a speck of dirt in some drinking water. The girl who swallows it becomes pregnant and, as her son, he is able to gain access to the hoarded light. It's especially interesting that almost invariably, the mother messes up and is punished with a monstrous or deformed child. This is another dimension to food as a symbol for desire and temptation - the mother gives in to curiosity or greed and crosses a line. "But the pretty flower tasted so sweet, that she couldn't help herself. She ate the other up too, for, she thought, 'it can't hurt or help one much either way, I'll be bound.'" Tatterhood's mother disobeys the rules and eats the weed and rose together. Prince Lindworm's mother behaves similarly. In India, Der Angule's mother eats the goddess-given cucumber right away instead of waiting as instructed, and Bitaram's mother eats a certain fruit even after hearing what the consequences will be. Tales like Nciç and Mkidech from North Africa and the Middle East often begin with a king who has many wives but no sons. They eat magical apples or pomegranates, and each bears a child; however, the youngest wife only receives half of a fruit, and so her son is stunted in growth. But in the end, these stories of falling to temptation still tend to work out. Tatterhood's birth seems disastrous at first, but she saves her sister. While the hero may seem unimpressive or upsetting at first glance, they ultimately pull through with a happy ending and become a blessing to their parents, even if they eat a few people along the way. (I'm looking at you, Prince Lindworm.) SOURCES

2 Comments

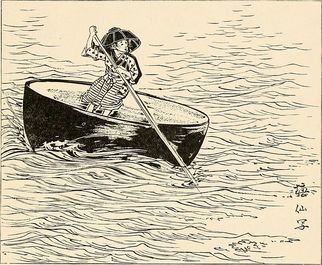

Issun Boshi is interesting because it’s such a unique variant of the Thumbling story, clearly native to Japan. Many others are simply the same story given different window dressing. Here, though, Issun Boshi’s narrative is fundamentally different. And Issun-Boshi shows up multiple times under different names (like Mamesuke), which I think is enough to establish it as its own variation.

The typical thumbling is a trickster and child-archetype with simple, even repetitive adventures and a circular narrative. Thumbling’s Travels is one example – although by age he’s a young adult and ready to go out into the world and make a living, by the end he’s back at home with his parents, still technically a child. Issun Boshi’s story, however, is of a boy growing into a man. The common elements are very interesting. The wish for a child: yes Emphasis on small size, creative use of objects (like a needle for a sword): yes Helping on the farm: no Tricking people: no Being swallowed: Yes, but in a typical thumbling story, it’s just one of those wacky things that happens when you’re an inch tall. The thumbling is a passive agent and must be rescued. In Issun-Boshi, it’s a battle to defend his princess. Finally, instead of remaining small all his life, Issun Boshi grows to full size, symbolically becoming an adult. Issun Boshi may have been recorded even before Tom Thumb. It’s one of the otogi-zoshi – a later term for popular stories written mostly in the Muromachi period from 1392 to 1573. It may have not become widespread until the early Edo period. Frustratingly, that’s a pretty big window of time, and I haven’t been able to find anything to narrow that down. Most early manuscripts have no dates and the identities of their authors are also a mystery. The copies that do have dates are usually retellings or copies from the Edo period. Haruo Shirane mentions that the oldest versions of Issun Boshi “[survive] in a mere three manuscripts” but doesn’t say which they are, and his source for this is presumably in Japanese, rendering it inaccessible to me for now. Issun Bôshi means “One Sun Boy” – a “sun” being equal to just over an inch. Thus, in English, he is sometimes renamed some variation on Little One-Inch. Unlike European tales, which tend to place stories in vague locations, it is very specific. Issun Boshi is born after his parents pray at Sumiyoshi sanjin, an ancient Shinto shrine in Osaka. He travels across Osaka Bay in a rice bowl and has an adventure in Kyoto. The Yanagita Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale lists multiple variants of this story under different names, such as Issunbo or Issun Kotaro. More distantly related, Virginia Skord mentions eleven otogi-zoshi tales about a dwarf hero winning a wife and climbing in social status. Issun Boshi is one category. The other two categories are Ko Otoko (Little Man) and Hikyūdono (Lord Dwarf). Ko Otoko, with its one-foot-tall hero Toshihisa, has a near-identical plotline to Lazy Taro. He eventually becomes the god of Gojo Shrine and his wife becomes Kannon, a goddess of childrearing who is Buddhist in origin. (Incidentally, Issun-Boshi’s princess is attacked while on her way to pray at Kannon’s shrine.) The story of Hikyūdono is a cross between Issun Boshi and Ko Otoko, but I haven’t been able to find more information on it yet. This story is probably one of the more well-known thumbling tales, and I think that from a storytelling standpoint, it may be better than the typical Thumbling. Sources

There was a point in time where Tommy Thumb was nearly equal to Mother Goose. This point was also where Tom Thumb underwent a transformation from a story that had been satirical, scatological and occasionally sexual to a story that would be told again and again for children. Not only that, but the story took on an educational nature, coupled with morals and spelling lessons.

It was not the only folktale that was toned down for a younger audience; even the Grimms sanitized and simplified the stories they retold. There's also the fact that Tom Thumb was a byword for small, so a Tom Thumb book was simply a little book. In one early primer, The Exhibition of Tom Thumb, the character himself addresses children "who are little and good like myself," which I think cuts straight to the reason why he was used so often in this context to teach children. For reference, the first full existing print version of Tom Thumb is from 1621. Tom Thumb's Alphabet, by an unknown author, begins "A was an archer, who shot at a frog." It first appeared in A Little Book for Little Children, published in the very early 1700s. According to the Oxford Companion to Children's Literature, it was first printed in America in 1765 in the primer Tom Thumb's Play-Book: to teach Children their letters as soon as they can speak. I don't know when it was first ascribed the title Tom Thumb. Tommy Thumb's Song Book (1744), by Nurse Lovechild (Mary Cooper), still exists reprints. Its sequel, Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Songbook (same year) features versions of many familiar rhymes, like London Bridge is Falling Down, but also some that might not be so familiar. Like one about bedwetting. Tom Thumb appears briefly "with his pipe and drum." The Travels of Tom Thumb over England and Wales (1746), by Dodsley. This story has nothing to do with Tom Thumb; the name is just used as a pseudonym. However, this was the first travel book for children, and described many different locations. The History of England, by Thomas Thumb, Esq. (1749): another pseudonymous work. The Monsters of Monster: a true and faithful Narrative of a most remarkable Phenomenon lately seen in this Metropolis; to the great Surprize and Terror of His Majesties good Subjects; Humbly dedicated to all the Virtuosi of New England. By Thomas Thumb, Esq. (1754). I have been unable to find further information on this work. "The Famous Tommy Thumb's Little Story-book: Containing His Life and Surprising Adventures. To which are Added, Tommy Thumb's Fables, with Morals, and at the End, Pretty Stories, that May be Either Sung Or Told. Adorned with Many Curious Pictures" (1760). Tom Thumb’s Playbook (1764) was a primer for children with alphabet rhymes and prayers. The Exhibition of Tom Thumb/Tom Thumb's Exhibition (1787), produced by Isaiah Thomas. Here, Tom Thumb introduces and narrates lessons on geography, animals and morals. Tom Thumb's Folio, or a New Penny Plaything for Little Giants (1779) contains first a pretty different version of Tom Thumb's life, and then some lessons on letters, vowels, syllables, and religious and moral lessons. One of the plot points is Tom teaching reading and writing to the inhabitants of a kingdom. This one is also printed as The Life and Death of Tom Thumb, the Little Giant, and included Tom Thumb's Alphabet. Tom Thumb's Picture Alphabet in Rhyme (c.1850) - "A is an angler, young but expert. B is a butcher who wears a red shirt." The Lilliputian Magazine; or, Children's Repository (c.1773) recounts several moral tales including that of King Tom Thumb, monarch of Lilliputia, as he fights wars and marries a princess named Smilinda. His educational side is emphasized and his army includes regiments like the "Alphabetical Infantry" and the "Intrepid Sons of Syntax." In Popular tales. Consisting of Jack the Giant-Killer, Whittington and His Cat, Tom Thumb, Robin Hood, and Beauty and the Beast (1810), instead of escaping the cow's belly with a laxative, Tom uses "comical tricks" of unknown nature - toning things down from previous versions. There is also an added moral: Tom has a troublesome life and dies young because his parents should have accepted God's will and been content instead of asking Merlin for a son. In The New Tom Thumb ... by Margery Meanwell (1815), written by William Mackenzie, Tom Thumb (a descendant of the famous fairytale Tom Thumb) hurts animals and immediately gets what basically amounts to karma. The entertaining story of Little Red Riding Hood ; and Tom Thumb's toy : adorned with cuts (1820?) features a version of the "Boy Who Cried Wolf" fable with a bull playing the role of the wolf. The title is somewhat baffling, as neither Tom Thumb nor toys make an appearance. The history of little Goody Two-Shoes : to which is added, The rhyming alphabet, or, Tom Thumb's delight (1820's). "A was an angler, and he caught a fish." Reading made quite easy and diverting: Containing symbolical cuts for the alphabet, tables of words of one, two, three and four syllables, with easy lessons from the Scriptures (c.1840), listed Tom Thumb as author, but otherwise did not mention him. The Novel Adventures of Tom Thumb the Great, Showing how He Visited the Insect World, and Learned Much Wisdom, Etc, by Louisa Mary Barwell (1838). This is a straightforward storybook, but with plenty of moralizing and discussion of insects and animals. Extraordinary Nursery Rhymes and Tales: New Yet Old (1876) is another one that changes up the story, focusing mainly on Tom growing up and finding a wife. Some were straightforward retellings of the fairy tale, although with small variants or excerpts - such as this one from around the 1850s, and History of Tom Thumb by Joseph Crawhall, a poem version that I haven't encountered before. The 19th century was filled with adaptations like Park's Tom Thumb (1836), The History of Sir Thomas Thumb, by Charlotte Mary Yonge (1855), The pretty and entertaining history of Tom Thumb (c1820), The History of Tom Thumb and Other Stories by an anonymous author, and William Raine's An Entertaining History of Tom Thumb. It also appeared in Halliwell's Popular Rhymes and Nursery Tales (1849) and Joseph Jacobs' English Fairy Tales (1890). Tom Thumb is a less popular character today, but his name still occasionally pops up as a byword for miniature. SOURCES I was researching a while back and came across an interesting analysis: the tale of Thumbling is the tale of the human spirit traveling through the world. This analysis bounces off a recurring idea that the soul is a tiny being. In The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, Maria Tatar suggests that Tom Thumb and Thumbelina were inspired by the Hindu belief of the soul (atman or purusha) as a "thumb-sized being." It seems far-fetched to me that this belief would have migrated through Europe and surfaced in stories like this. I think they were born simply out of the popular interest in what is miniature and fantastical. She seems to be referring to the ideas set forth in the Upanishads; however, here the soul (atman or purusha) is not described as a thumbling, but as a tiny flame dwelling in the forehead or the heart. It is both infinitely small, the size of a thumb or the thickness of a hair, yet at the same time infinitely huge. The thumbling soul sometimes appears in Christian imagery (Philosophy and the Self: East and West). In Masolino da Panicle's fresco of the Crucifixion, a tiny man - the soul - emerges from the dying thief's mouth (pictured right). In a 1520 French stained glass window in the Art Institute of Chicago, the soul of Judas Iscariot is also a tiny man, appearing from his stomach. And in the 1443 "Death of the Virgin" mosaic and other similar artwork, Christ cradles the infant-sized soul of Mary.

Spence suggests in British Fairy Origins that fairies are inspired by images of ghosts - thus fairies are tiny because they resemble the miniature "mannikin soul." Religion in Essence and Manifestation mentions again the Hindu ideas of the soul. It also describes the Toradja of Celebes [Sulawesi] as imagining a "mannikin" soul, the tonoana. The tonoana is actually one of three souls that each person possesses, and apparently leaves the body to become a werewolf. James Frazer says in The Golden Bough that in America, the Hurons, Nootkas, and the tribes of the Lower Fraser River all have similar ideas of the soul as a miniature, transparent double of the body. A Wailaki tale from California features a dream doctor who has to hunt down an escaped soul. The soul "resemble[s] a miniature person," and is found sitting by a little fire it's built. Frazer adds that this is a belief in Malaysia, too. This is a bit of a blanket statement over a group of diverse and complicated beliefs. In Malay tradition, some tribes held that there were actually more than one soul or kind of soul. I did find that Religion in Essence and Manifestation echoes Frazer, citing a chant from Malacca (a state in Malaysia) that refers to the soul as "little" and "filmy" and describes it as a bird. If you go to Wikipedia, it draws from James Hastings' Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 15, speaking of the soul or "semangat" (essence) being a miniature copy of the body, which flashes from place to place and is compared to a bird. This part of the soul can can leave the body during trances or sleep, and after death, passes into another creature or plant. In some Chinese stories, the soul is again a tiny double of the body, but this is a relatively rarer and newer idea compared to other Chinese descriptions of the soul. So the idea of the miniature soul pops up all over the world. The Religion of the Veda basically says all these ideas of the soul as a tiny man probably originated in the Upanishads with the thumb-sized flame. Chronologically speaking, those were recorded around 800-200 B.C., well before any of the other examples listed here. It still seems like a big step to say that the fairytale characters were descended from a Hindu description of the soul. However, I also remembered that there is a story called "S’homonet com un gri," or the little man as small as a cricket. In this Catalan tale, a couple meets an insect-sized boy, who calls them his parents and helps them around the farm. Thus far, it is a typical type 700 tale; however, he then reveals that he's the spirit of their deceased son, returned temporarily from heaven to aid them. So maybe Maria Tatar is onto something. However, even though the image of the miniature person could have stemmed from religious art or spiritual imagery, I still think thumbling tales are inspired simply by the appeal of the miniature. SOURCES

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed