|

The akhlut, in Inuit legend, is an orca-like creature which can turn into a wolf on land, or a giant wolf, or a hybrid of wolf and orca (with many modern artists taking a crack at visualizing it - see examples here). As pack animals and dangerous hunters, orcas and wolves do have a lot in common. Some users on Wikipedia and the Offbeat Folklore Wiki have done excellent digging to establish that the "akhlut" is a very modernized take on a belief.

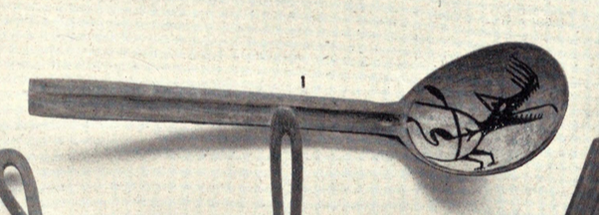

Akhlut is actually a misnomer; "akh'lut" is the name for the orca among some indigenous peoples around the Bering Sea. (Compare the differently Romanized Yupik word "arrlug," found in Freelang's online dictionary). In 1899, Edward William Nelson, an American naturalist, published his studies collected from the west coast of Alaska and east coast of Siberia. The geographical area encompasses Inuit and Siberian Yupik groups. Among other mythical creatures, Nelson mentioned a shapeshifting monster known as the “kăk-whăn’-û-ghăt kǐg-û-lu’-nǐk": "It is described as being similar in form to the killer whale and is credited with the power of changing at will to a wolf; after roaming about over the land it may return to the sea and again become a whale. While in the wolf form it is known by the above name, and the Eskimo say they know that this change takes place as they have seen wolf tracks leading to the edge of the sea ice and ending at the water, or beginning at the edge of the water and leading to the shore. ... These animals are said to be very fierce and to kill men ... This belief is prevalent among all the Eskimo along the shore of Bering sea." (Nelson, p. 444) "Kǐg-û-lu’-nǐk" means the gray wolf (Nelson, p. 322). Nelson included rationalizations, saying that the killer whale is the clear inspiration and that the vanishing wolf tracks are caused by ice breaking off the shore. He also mentioned other mythical creatures such as white whales (belugas) that also take reindeer form. He included photographs of indigenous art where wolves transform into orcas, or creatures that have aspects of both animals. After Nelson’s work, the idea of this creature has been simplified and passed around. It was described under the name "akhlut" in Gill and Sullivan's Dictionary of Native American Mythology (1992, p. 8). The dictionary cites Tennant and Bitar's Yupik Lore: Oral Traditions of an Eskimo People (1981), but I think this was a mixup. A) Tennant and Bitar don't mention any myths about orcas, and B) Gill and Sullivan's description is very similar to Nelson's in details and wording. Gill and Sullivan were cited by Carol Rose in her reference book Giants, monsters, and dragons: an encyclopedia of folklore, legend, and myth (2001, p. 10). So the akhlut story spread like many similar factoids, through reference books repeating each other. These stories usually focus on the evil of the akhlut; as Carol Rose wrote, extrapolating wildly, "this being emerges from the ice-floes to hunt for human beings in the guise of an enormous wolf. The Inuit, upon seeing huge wolf tracks that terminate at the edge of the ice, know that they are in peril and are quick to retreat. They recognize this spot as dangerous territory, for it is the place where an Akhlut has changed back into this killer whale form and may reemerge to kill them" (Rose, pp. 10-11). One story floating around on the Internet snagged my attention: a supposed origin myth for the akhlut. In this account, there was once a man so fascinated by the ocean that he began to spend all of his time there, and slowly to become more and more like an animal, until his own tribe didn’t recognize him and cast him out. Deadset on revenge, he transformed into a beastly wolf. However, his love for the ocean still tugged at him, so he became an orca. Since then, the creature known as the akhlut spends time in the ocean as an orca but comes ashore as a wolf when hungry (whether for food or for revenge - it varies between tellings). This account has been circulating around a few blogs and forums, and even made it into a book in 2023 (Natalie Sanders' The Last Sunset in the West), but something about it seemed off. After some digging, I discovered that this origin story was attached to the virtual pet site Magistream, which includes numerous mythical creatures. A user first requested that the akhlut be added to the bestiary in March 2010 (source). In December 2011, the akhlut was added, along with an origin story (source). This telling explains more of the internal logic. The man fated to become the first akhlut doesn’t just wander off to become a wolf (although that is not outside the bounds of possibility in folktales). Instead, he is killed by wolves, and his restless spirit shifts between shapes as it is “torn between his love for the water and a consuming need for revenge.” Note that the Inuit people are never mentioned; the story is instead set in a fictional land called Arkene. I tried reaching out to the Magistream moderators for more info, but it seems that the writer who created the Akhlut’s description has moved on from the site since 2010. A close rewording of this story was added to the Cryptid Wiki on August 10, 2015. This version is less descriptive, garbles some of the details, and attributes the story to Inuit legend, apparently for the first time. The Cryptid Wiki's retelling seems to be the most widespread version, copied on various blogs. The Whale-Wolf The myth that Nelson collected fits into a much broader context. Many indigenous peoples had deep respect for the orca, which was associated in some cultures with hunting or with the afterlife. In many cultures, there was a belief that the killer whale and the wolf were the same being. Much like the images collected by Nelson, these were depicted with aspects of both animals in ritual art. The Siberian Yupik believed that the killer whales became wolves during the winter. Unlike what we've seen of the "akhlut" so far, they were revered and seen as helpers. As Edward J. Vajda wrote: "The killer whale... and wolf were considered sacred and could not be killed... Killer whales were also revered as protectors of hunters; it was also thought that the killer whale became a wolf in winter and devoured the reindeer unless some of the reindeer submitted to the hunters. Ritual meals were concluded by throwing a piece of meat into the sea to bless and thank the killer whales who had made the catch possible." The Kwakwaka'wakw of British Columbia also believed that killer whales could transform into wolves (or humans) at will (Francis and Hewlett, p. 117). They made offerings to the orcas to request food such as seals, and believed that orcas/wolves could bestow supernatural powers such as healing (McMillan, p. 322). Similarly, the Nuu-chah-nulth viewed the whale-wolf as benevolent and helpful, with both wolves and whales being patrons of hunting. People avoided killing orcas. As an early-20th-century informant stated, "The killer whales are wolves. Wolves sometimes run through caves into the water and turn into killer whales. The tail turns into the big fin on the back." The wolf-orca connection plays a part in several origin myths for the tlukwana or "Wolf Dance," an important traditional mid-winter ceremony. Relevant to the "origin myth" for the "akhlut," one story describes a young man who is adopted by the wolves and taught to hunt marine mammals. He returns to his village in “Killer Whale clothes” to teach his people the tlukwana (McMillan, pp. 314-316). In Haida lore from British Columbia, a mythical creature called the Wasco could transform from an orca to (depending on the version) either a wolf or a bear. It hunted whales. (Barbeau, p. 305; Deans, p. 58). There is a story where a man killed the Wasco, skinned it, and was able to gain its power by wearing the skin. The kăk-whăn’-û-ghăt kǐg-û-lu’-nǐk - or its modernized counterpart, the akhlut - is part of a mythical context in which people and animals change their shapes at will. As part of this, there is often a connection specifically between orcas and wolves which we find in indigenous myths from all around that geographic area. Nelson gives only a tiny bit of information, and it's hard to say how much might be influenced by his retelling and interest in rationalizing. For another instance of aquatic mammals, there are reports of stories from Nunivak Island that belugas could transform into wolves or mountain sheep (Hill, p. 53). REFERENCES

0 Comments

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed