|

Where did the tiny flower fairy come from? A lot of people blame Victorian authors, but the idea's older than that. The finger's also been pointed at William Shakespeare, but although he codified them and made them famous, he was not the one to introduce tiny fairies either.

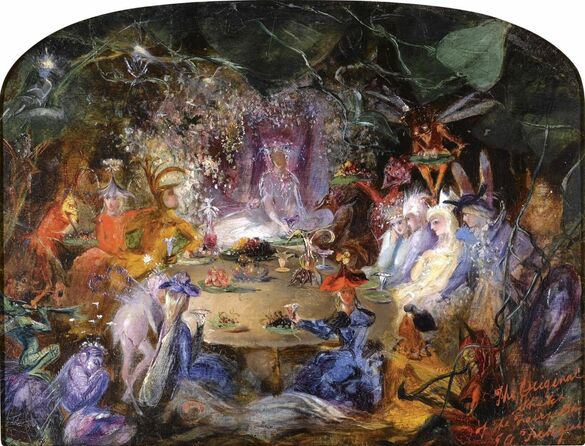

Going back into medieval legend and earlier, human-scale fairies seem to be the rule. Nymphs and fauns were the nature fairies of Greek mythology, although they were of human stature. In medieval literature, fairies usually seemed to be human-sized. At their smallest, they were the size of children, like Oberon in "Huon of Bordeaux." In John Lyly's play "Endymion" (1588), the fairies are "fair babies," probably played by children. However, occasional appearances by very tiny fairies have survived. In Gervase of Tilbury's Otia Imperialia ("Recreation for an Emperor") c.1210-1214, we get the first truly miniature fairies: “portunes,” little old men half an inch tall. There's been some debate over whether this was a textual error, and whether it should be read as closer to half a foot tall. However, I don't see any reason why they couldn't be half an inch tall. In fact, people were probably familiar with the idea of tiny otherworldly beings. In the Middle Ages, both demons and human souls were often portrayed as very tiny. In one medieval story, a priest celebrating a Mass for the dead suddenly sees the church filled with souls. They appear as people no bigger than a finger ("homuncionibus ad mensuram digiti"). In an Irish tale transcribed around 1517, King Fergus mac Leti meets Iubhdan and Bebo, rulers of the Luchra. One of them can stand upon a human man's palm or drown in a pot of porridge. These beings are clearly fairies. Iubhdan's hare-sized horse is golden with a crimson mane and green legs (red and green being traditionally associated with the fae). They bestow Fergus with magical gifts, like shoes which allow him to walk underwater. The story is an expansion of previously known tales where Fergus encounters "lúchorpáin," or "little bodies," evidently some type of water-dwelling creature and possibly the predecessors of the modern leprechaun. Reginald Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) gives a list of bogeymen and fairies. Included in the list is "Tom thombe" - a character no bigger than a finger. There are other clues that might connect the supernatural to the miniature: the fairies turn hemp stalks into horses, and witches sail in eggshells or cockleshells. Then came Shakespeare. In A Midsummer Night's Dream (c. 1595), we finally find tiny nature fairies. Oberon and Titania are nature gods. Their servants have plant names like Peaseblossom and their tasks include dewing the cowslips and making clothing from bats' pelts. Queen Mab appears in Romeo and Juliet (1597) and is a diminutive force to be reckoned with. In The Tempest (c. 1610), the fairylike Ariel is not exactly a fairy, but he does share their size and affinity with flowers: "In a cowslip's bell I lie." This began an obsession. Another play, "The Maid's Metamorphosis," was published around 1600. Fairies named Penny, Cricket and Little Pricke "trip . . . lightly as the little Bee" and sing: ‘I do come about the coppes Leaping upon flowers toppes; Then I get upon a Flie, Shee carries me abouve the skie." In the first known version of Tom Thumb, printed in 1621, Tom's fairy-made wardrobe consists of plants and found objects. His hat is an oak leaf. In one scene, he sleeps “upon the top of a Red Rose new blowne.” Michael Drayton's "Nymphidia" came out in 1627. This long narrative poem shrinks Shakespeare's fairies even further to the point where Mab and all of her servants can comfortably house themselves inside a nutshell. Tom Thumb, appropriately, appears among them, and a fairy knight wears armor fashioned out of insect parts. Drayton also wrote "A Fairy Wedding" (1630) with a bride robed entirely in petals. In William Browne of Tavistocke's third book of Britania's Pastorales, Oberon is "clad in a suit of speckled gilliflow'r." His hat is a lily and his ruff a daisy. A servant wears a monkshood flower for a hat. Elsewhere, Browne’s fairies guard the flowers: "water'd the root and kiss'd her pretty shade." Robert Herrick, writing in the 1620s and 1630s, brought us "The beggar to Mab, the Fairy Queen," "The Fairy Temple, or Oberon's Chapel," and "Oberon’s Feast." "Oberon's Clothing" is a poem of similar fare. The author is unknown but has been attributed to Simon Steward or possibly Robert Herrick. Lady Margaret Newcastle's "The Pastime, and Recreation of the Queen of Fairies in Fairy-land, the Center of the Earth" (1653) is much the same thing. These works deal with the food, clothing, housing, transportation, and hobbies of flower fairies in exquisite detail. These were smaller, cuter forms of the folklore fairy, and this whimsical form of escapism had captured the popular imagination. However, some of these works may also have served to critique the excesses of royalty. Marjorie Swann suggested that William Browne was subtly mocking King James and other rulers by parodying their lavish banquets and hunting parties. This interest in the supernatural was not just literary. There were witch hunts actively going on at this time. A Pleasant Treatise of Witches (1673) purports to be a collection of factual accounts of supernatural phenomena. In Chapter 6, a woman sees a tiny man - only a foot tall on horseback - emerge from behind a flowerbed. He introduces himself as "a Prince amongst the Pharies." Later, his army appears at dinner to "[prance] on their horses round the brims of a large dish of white-broth." One soldier slips and falls into the dish! Despite the connection with flowers and the inherent comedy of the fairies' size, there was still a great danger to anyone involved with them. In this particular tale, the woman quickly wastes away and dies after her otherworldly encounter. All the same, the cute fairy continued strong into the 18th century with Alexander Pope's The Rape of the Lock (1717) and Thomas Tickell's Kensington Garden (1722). Plays like "The Fairy Favour" by Thomas Hull, produced in 1766, used fairy imagery and Shakespearean allusions to flatter royalty, continuing a theme popular with Queen Elizabeth. However, Elizabethan fairy literature included works like The Faerie Queene with heroic human-sized fae. Now, the sprites of "The Fairy Favour" slept in the shade of a primrose and wore robes made from butterfly wings. The Rape of the Lock, a parodic work very much in the tradition of Nymphidia, is particularly significant. Drawing on the work of Paracelsus and the esoteric Comte de Gabalis, it presents a pantheon of elemental spirits. There are sylphs, gnomes, nymphs and salamanders, which Pope makes the reincarnated souls of the dead. They are tiny enough to hide in a woman's hair and dangle from her earrings. (As with other fairy literature, their size is a source of comedy.) Most importantly, they have "insect-wings." A 1798 edition, illustrated by Thomas Stothard, gives the sylphs butterfly wings. This is the earliest known appearance of the modern winged fairy. In the 19th century, the movement of folklore collecting became a significant force. In the folklore that was collected, and the writings inspired by it, we meet wave upon wave of miniature flower fairies. In Teutonic Mythology volume 2 (1835), Jacob Grimm described elves and wights ranging from "the stature of a four years' child" to "measured by the span or thumb." Thomas Crofton Croker, in Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland (1825), explained that the foxglove is known as the Fairy Cap "from the supposed resemblance of its bells to this part of fairy dress." This inspired Hartley Coleridge to write of "Fays sweetly nestled in the foxglove bells." In British Goblins by Wirt Sikes (1880), we learn that foxgloves serve the Welsh ellyllon for gloves. Anna Eliza Bray's pixies use tulips as cradles (1879). And the "greenies" in James Bowker's Goblin Tales of Lancashire (1878) perhaps show the influence of Nymphidia, with a "dainty dwarf in a burnished suit of beetles' wing cases." At the same time, new fairy tales and fantasy literature were being produced. In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen published the story of Thumbelina. The thumb-sized heroine is born from a flower and eventually becomes queen of the winged flower fairies. The first of these people is introduced as "the angel of the flower" (Blomstens Engel), and we learn that such a being dwells inside every blossom. In 1839, Andersen produced "The Rose Elf" (Rosen-alfen) with a main character "so tiny that no mortal eye could see him" who lived in a rose. These fairies for children, however, took on a strong educational bent. The Heroes of Asgard, by Annie Keary (1856) turned the Norse Ljósálfar into tiny elves who tended flowers under the tutelage of their "schoolmaster," the god Frey. This story was frequently reprinted in publications like A phonic reading book (1876). Other fairy-centric books included The Novel Adventures of Tom Thumb the Great, Showing How He Visited the Insect World by Louisa Mary Barwell (1838); Fairy Know-a-bit; or, a Nutshell of Knowledge (1866) by Charlotte Tucker; and Old Farm Fairies: A Summer Campaign in Brownieland Against King Cobweaver's Pixies by Henry Christopher McCook (1895). These used a fantasy framework to teach children about the natural world, encouraging them to examine insect and plant life. But there was a stark divide between fairies for children and fairies for adults. In George Macdonald's Phantastes (1858), the fairies are explicitly flower fairies - hiding in "every bell-shaped flower" - but they are grotesque and not at all benevolent. This was also the era of Victorian fairy paintings like those of Richard Dadd, Richard Doyle, and John Anster Fitzgerald. Victorian fairy painting was a movement in and of itself, hitting its high point from 1840 to 1870. These paintings often featured obsessive levels of minute detail, but could have an eerie, ominous, even violent atmosphere. In Dadd's intricate "Contradiction: Oberon and Titania" (c. 1854), the fairy queen inadvertently crushes a mini-fairy under one foot. Fitzgerald's work sometimes held references to drugs and hallucinations, as in his painting "The Nightmare." And a lot of Victorian fairy art was sensual. In a society otherwise bound by the rules of propriety, fairies were allowed to be barely-clothed, undeniably erotic beings. J. M. Barrie, author of Peter Pan, transformed the fairy genre again at the turn of the century. He published his first Peter Pan book, The Little White Bird, in 1902; there, his fairies disguise themselves as flowers to avoid attention. Barrie's most famous fairy is, of course, Tinker Bell. She first appeared (as a light projected by a mirror) in Barrie's 1904 play, and quickly came to dominate the modern perception of fairies. According to Laura Forsberg: "[Barrie] changed the terms of the discussion around fairies from observation and imagination to nostalgia and belief. While the Victorian fairy was always accompanied by the adult’s urging the child to look closer at the natural world, Tinkerbell was a trick of mechanical lighting that would be revealed as a fraud if the child approached. Tinkerbell so captured the public imagination that she overshadowed the Victorian fairies who preceded her." (p. 662) According to author Diane Purkiss, the cult of the flower fairy faltered with the advent of the First World War. A jaded world was no longer interested in cutesy twee pixies. The human-sized elves of J. R. R. Tolkien set a new standard for fantasy literature. But as far as I can see, the tiny fairy continued to conquer media. The first of Cicely Mary Barker's wildly popular "Flower Fairies" picture books appeared in 1923. Enid Blyton, a classic children's author, described fairies painting the colors of nature. "To Spring," a 1936 cartoon, shows microscopic gnomes laboring to bring the colors of spring. In the 21st century, the Disney Fairies franchise is a marketing behemoth and "fairy gardens" have taken over Pinterest. This reaches into modern belief in fairies. The Cottingley Fairies were a famous hoax in the 1910s which even took in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. His book The Coming of the Fairies, released in 1922, included many testimonials from fairy-believers. Similarly, in 1955, Marjorie Johnson began the work that would eventually become Seeing Fairies, released in English in 2014. It's a collection of "fairy sightings" from many different people who believed they had genuinely seen otherworldly beings. In many of these cases, the fairies they reported were small winged creatures living in nature. It is true that today the tiny flower fairy is frequently viewed with disdain as something only for children. Works on fairies for older readers usually take pains to specify that these are not the same-old-same-old cute fairies, but the ancient, bloodier, sexier versions. A typical example: The Iron King by Julie Kagawa (2010) dismissively references Tinker Bell as the usual human concept of fairies, calling her "some kind of pixie with glitter dust and butterfly wings," while introducing a darker and crueller Fairyland. There is no longer the same adult fascination with miniature fae that flourished in the 17th and 19th centuries. It's still unclear where flower fairies originally came from. Shakespeare undoubtedly popularized them, but he apparently expected his audience to take his incredibly miniature nature spirits in stride. There are surviving hints of tiny fairies in literature predating him. And that brings me back to the ghosts of medieval art. Fairies and ghosts overlap. The further you go back, the more intertwined they are. Anna Eliza Bray's pixies (the ones sleeping in tulips) are "the souls of infants" who died unbaptized. The elementals in The Rape of the Lock are the spirits of the dead. In The Canterbury Tales (c. 1400), Geoffrey Chaucer calls Pluto (Roman god of the underworld) the king of the fairies. And it's not just in Europe; in the lore of West and Central Africa, ancestral spirits can be diminutive figures who behave a lot like European fairies. This makes that medieval story about finger-sized souls, particularly fascinating. Sources

0 Comments

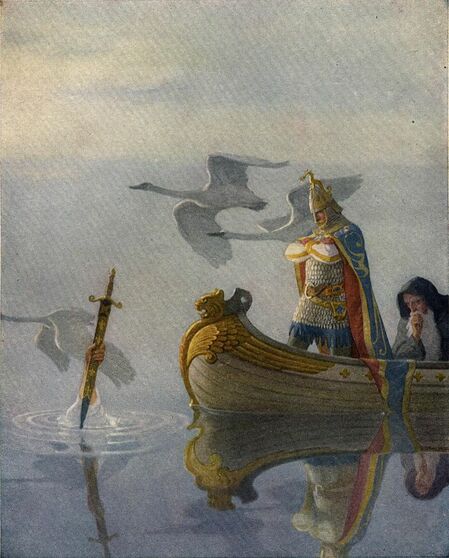

There are two famous accounts of how King Arthur won his sword.

This has led to some confusion. Different sources may use one sword or the other or both. In many works, such as the 1981 film Excalibur and the 1998 miniseries Merlin, the two swords are one and the same. This has caused a reactionary response: these should properly be two different weapons, wielded by Arthur at different times. On a DeviantArt submission in 2006, multiple users bobbed in to remark that Excalibur, the sword from the lake, was not the same as the Sword in the Stone. A 2014 post on StackExchange said much the same thing. The sword in the stone, according to sources like these, is actually called Clarent. Going back to the earliest sources: Arthur's sword in Welsh was named Caledfwlch. This could have developed into Excalibur. That's another debate. Throughout the history of Arthurian legend, Excalibur (or Caliburn, Caliburnus, Escalibor, Chalabrum, etc.) has always been The Arthurian Sword. King Arthur bears it, or one of his champions like Gawaine wields it for him. The Sword in the Stone appears in Robert de Boron's Merlin, but doesn't get a name. In the Vulgate Merlin Continuation, Escalibor is the sword pulled from the stone, which Arthur eventually passes down to Gawain. In the post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin, they are separate swords. The sword from the stone is broken, and Arthur receives Escalibor from the lake as a replacement. The Suite also introduces Excalibur's magical scabbard. In Thomas Malory's Morte d' Arthur, drawing from many Arthurian sources, Arthur draws the sword from the stone. It is not named until Chapter IX, where it's called "Excalibur," shining with "light like thirty torches." This sword eventually breaks, and the Lady of the Lake gives Arthur . . . another sword named Excalibur. Malory's pretty inconsistent throughout this work. It may be that he included Excalibur's name early on by mistake. All the same, here it seems that Arthur had two separate swords and both were named Excalibur. Now for Clarent. Clarent appears in one source: the Alliterative Morte Arthur. It is Arthur's beloved, sacred sword used only in ceremonies and knightings. Arthur views it with reverence and uses his other sword, Caliburn, for battle. Mordred gains Clarent through his treachery and, eventually, slays Arthur with it. There are a few possible sources for the name. In the Estoire de Merlin, Arthur uses the battlecry "Clarent." There was also a city of Clarent in Sorgalles that was part of Arthur's dominion. An interesting similarity exists in the romance The history of the valiant knight Arthur of Little Britain, where a knight named Arthur wins a sword called Clarence. But nowhere else does Clarent appear, and it is never identified as the sword in the stone. It has generally survived as a footnote. In 1895, Selections from Tennyson described it rather dismissively as Arthur's "second-best sword"! However, some Arthurian scholars have taken note of it. In 1960, William Matthews theorized that the Alliterative Morte's two swords were an attempt to reconcile confusing accounts of what swords Arthur used and when. "[I]t seems likely that [Clarent] may be the sword-in-the-stone . . . and that Caliburn is, as usual (though not always), the sword of the Lady of the Lake." Similarly, Kathleen Toohey reviews Arthur's reverential treatment of the sword: "from what we learn of Clarent no better role could have been found for the sword in the stone than the one assigned to Clarent." Note those phrases, though: "It seems likely." "Not always." "From what we learn." "Could have been." Anyone who ties the obscure name Clarent to the sword in the stone is theorizing. It's a valid theory, but still a theory. There's no solid evidence for it. Unhelpfully, for some time there was a Wikipedia article identifying Clarent as the Sword in the Stone. It was nominated for deletion in September 2012. Clarent has gotten a popularity boost in recent years. It's shown as Mordred's sword in the Japanese light novel Fate/Apocrypha (2012-2014). Its origin is very close to that of the canonical Clarent, but I can't find any mention of it being the Sword in the Stone. There are alternate options. Nightbringer, an extensive online Arthurian dictionary, suggests that the sword in the stone could be identified with Sequence, another sword belonging to Arthur, which was borrowed by Lancelot. Alternately, based on romances where Gawaine inherits Arthur's first sword, maybe the sword he wields in Malory - "Galatine" - is the original sword in the stone. (I don't quite follow this, since in those romances the original sword is Escalibor.) These guesses hit the same issues as the Clarent theory: namely, they're guesses. We have a confusion of sources where Excalibur is sometimes the Sword in the Stone and sometimes its replacement. Or, as in Malory, both! Ultimately, the Sword in the Stone cannot be definitively linked to Clarent, Sequence, Galatine, or any of the swords belonging to Arthur . . . except for Excalibur. Sources

Hey guys! Be sure to check out this short documentary by Molly Likovich, analyzing the story of Red Riding Hood. Molly very kindly invited me to interview, so I am in there at a few points (look for Sarah Allison). This is one of the most omnipresent fairytales in our culture and the video provides a really interesting look at its origins. Molly has other similar video essays on her channel. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed