|

The Vita Merlini is a Latin poem written around 1150, probably by Geoffrey of Monmouth. This poem has, among other things, one of the earliest mentions of Morgan le Fay and Avalon. She is not Arthur's sister, but an otherworldly healer who carries him away after his death. She is one of nine sisters.

The island of apples which men call “The Fortunate Isle” gets its name from the fact that it produces all things of itself; the fields there have no need of the ploughs of the farmers and all cultivation is lacking except what nature provides. Of its own accord it produces grain and grapes, and apple trees grow in its woods from the close-clipped grass. The ground of its own accord produces everything instead of merely grass, and people live there a hundred years or more. There nine sisters rule by a pleasing set of laws those who come to them from our country. She who is first of them is more skilled in the healing art, and excels her sisters in the beauty of her person. Morgen is her name, and she has learned what useful properties all the herbs contain, so that she can cure sick bodies. She also knows an art by which to change her shape, and to cleave the air on new wings like Daedalus; when she wishes she is at Brest, Chartres, or Pavia, and when she will she slips down from the air onto your shores. And men say that she has taught mathematics to her sisters, Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Tyronoe, Thitis; Thitis best known for her cither. In the Vita, Avalon (or at least, "The Fortunate Island") is an otherworldly paradise ruled by women. A similar concept is the Land of Women in the 8th-century Irish narrative "The Voyage of Bran." It is also an otherworldly island populated by immortal maidens. Then there's the 12th-century German "Lanzelet," where Lancelot is raised by the queen of the sea-fairies on the island of Meidelant, which is otherwise populated only by women. Morgen is the most important here, with her sisters only footnotes. Variants of Morgan's name appear all over the place, but its origins are too ancient to truly determine. She is often closely associated with water. The Vita calls her and her sisters "nymphae." Morgan is called "dea quadam fantastica" by Giraldus Cambrensis, "Morgne the goddes' in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and 'Morgain la deesse' in the Prose Lancelot. Morgen is the oldest recorded form of Morgan's name. John Rhys theorized that it meant "sea-born," from Morigenos. A similar name is Muirgen, given to a mermaid in Irish myth. It's also been proposed that Morgan derives from the Welsh mother goddess Modron. Modron is the daughter of Afallach, a name closely related to Avalon. But back to her eight sisters. The list in Vita Merlini, as a whole, has a Greek look. One writer, David Dom (King Arthur and the Gods of the Round Table, 2013) makes a heroic attempt to connect each name to a Celtic goddess, but by the end even he is left pulling Greek goddesses instead of Irish or Welsh. There's a clear correspondence to the nine Muses of Greek myth. Morgen is a muse of medicine and science, while the last sister is associated with the cither, a musical instrument. There's also a group of nine women associated with the French Ile de Sein, according to De Chorographia by Pomponius Mela (d. AD 45). "Sena, in the Britannic Sea, opposite the coast of the Osismi, is famous for its oracle of a Gaulish god, whose priestesses, living in the holiness of perpetual virginity, are said to be nine in number. They call them Gallizenae, and they believe them to be endowed with extraordinary gifts to rouse the sea and the wind by their incantations, to turn themselves into whatsoever animal form they may choose, to cure diseases which among others are incurable, to know what is to come and to foretell it. They are, however; devoted to the service of voyagers only who have set out on no other errand than to consult them." The Gallizenae are pretty much identical to Morgen and her sisters. I would venture to say that the author of the Vita Merlini was inspired by both the Gallizenae and the Muses. The concept of nine maidens recurs throughout world mythology - for instance, Rán, Norse goddess of the sea, had nine daughters. It also crops up frequently in Arthurian legend. In the Welsh poem "Pa Gur yv y Porthur," Cei (Kay) is mentioned as having killed nine witches (the number nine is repeated frequently in this poem). Nine maidens living on the island otherworld of Annwfn use their breath to kindle a magic cauldron in The Spoils of Annwn. (It's been suggested that these two groups are the same.) And in Peredur, the hero kills the nine sorcerous Hags of Gloucester. Those are all villainous examples, though, while Morgen's sisters in Vita Merlini are benevolent. Of the nine names, there are three clear groups: the M names, G names and T names. Morgen, Moronoe, Mazoe. Only Morgen's name is familiar. The others may be original creations, although plenty of scholars have looked for connections to other mythological characters. There are plenty of Celtic goddesses with M names, like Morrigan and Macha. A sister of Morgan named Marsion or Marrion appears in the 13th-century La Bataille de Loquifer. They are accompanied by an attendant, making this yet another trio. "Dame Marse" is one of the fays alongside Morgain, Sebile, and Dame Oriande in the Chanson D'Esclarmonde, also 13th century, a continuation of Huon de Bordeaux. In the post-Vulgate Suite de Merlin, a beautiful fay named Marsique obtains Excalibur's scabbard for Gawain. Each one seems to be a single one-off mention. I may be playing phonological games here; there might not be any connection between Marsion, Marse and Marsique, let alone a connection to Moronoe or Mazoe. However, the similarities are intriguing. Marsique is the most interesting to me. Since the scabbard was last seen when Morgan lobbed it into a lake, this could imply a connection between Marsique, the lake, and Morgan. We also know that she helps Gawain fight a sorcerer named either Naborn or Mabon. In the Mabinogion, Mabon is also the name of a son of Modron, the Welsh goddess who may be a proto-Morgan. This is similar to Esmeree the Blonde, a Welsh princess and lover of Gawain's son Guinglain. A sorcerer named Mabon turned her into a serpent when she wouldn't marry him, and she was only freed through Guinglain's kiss. Meanwhile, in an Italian romance, Gawain's otherworldly lover is the Pulzella Gaia (Merry Maiden), the daughter of Morgan. The Merry Maiden can take snake form apparently at will, and later in the story Morgan imprisons her and turns her into a mermaid. So there are stories where Gawain (or his son) fights for a fairy maiden who gives him magical aid, and who is associated with water, serpents, and Morgan le Fay. I found one French reference to a mountain named "Marse" or "Marsique." Pope St. Gregory's Dialogues. A story is related of the monk Marcius of the mountain of Marsico. Marsico could be Monte Marsicano - there are two Italian mountains by this name. Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton This is where it really begins to seem likely that the writer is making up names as he goes along. Lucy Allen Paton writes, "The necessity of naming her eight sisters is apparently embarrassing to the poet; he economizes by ringing three changes on one name . . . and his ingenuity deserts him completely before he reaches the eighth." However, Paton also suggests that the G could be a C, and that this is a reference to the Greek nymph Clytie, daughter of Oceanus. This theory has no real evidence. A 1973 edition of the Life of Merlin suggested a connection to Cliodhna, an Irish goddess. In various myths, she was carried away by a wave, leading to the common phrase "Clíodhna's Wave" and inviting an association with water nymphs. In the 12th-century narrative "Acallam Na Senórach," she is a mortal woman and one of three sisters. Tyronoe, Thitis, and Thitis best known for her cither. Tyronoe's resemblance to Moronoe increases the rhythmic quality of the names. There is a princess named Tyro in Greek mythology. Weirdly, depending on translation, two sisters are either named Thiten and Thiton, or they're both Thitis, only distinguished by one's musical hobby. Thiten could be Thetis, a Greek goddess of water. Combined with Morgen and Clytie, this gives us a theme of goddesses connected to water. A connection to the Greek goddess Thetis seems very possible. There was also a Greek goddess Tethys, and both were tied to water. In a 13th-century German romance, Jüngere Titurel, 'Tetis' operates as a sorceress. Interestingly, if you go back to the "Acallam Na Senórach" for a minute, Cliodnha drowns at the Shore of Téite. This place got its name because of a previous drowning, that of a woman named Téite Brecc and her companions. However, this may be grasping at straws. The reference to "cither" remains mysterious. It's unclear what was meant, although it might be a guitar or a Welsh harp like a zither. (Both derive from the Greek word "cithara." Morgen/Morgan's sisters haven't appeared in other material. This is the only source that makes her one of nine siblings. However, it is very common for her to appear as one third of a trio. The number three was sacred in Celtic culture and some gods or goddesses appeared in triads. For instance, the Morrígan, an Irish example with a very similar name, was sometimes described as a trio with the names Badb, Macha and Nemain. The Matronae, or Mothers (similar to Modron the mother goddess) appeared in threes and were venerated from the 1st to 5th centuries. In Thomas Malory, Morgan le Fay completes a trio with her sisters Elaine and Margawse. They are the daughters of Gorlois and Igraine, and half-sisters to Arthur. Malory's Morgan seems to enjoy traveling in a group. She shows up at various times with companions like the Queen of Northgales, the Queen of Eastland, the Queen of the Out Isles, and the Queen of the Wasteland, all evidently sorceresses like herself. In Li Jus Adan or Le jeu de la Feuillee (c. 1262), Morgan appears with two attendants, Maglore and Arsile, eating at a table which was put out for the fairies. Morgain and Arsile bestow blessings on their hosts, but Maglore, like the fairy in Sleeping Beauty, gets angry that no knife was put at her place and declares ill luck on the men who set the table. In L'Amadigi, an epic poem written by Bernado Tasso in 1560, Fata Morgana has three daughters: Morganetta, Nivetta and Carvilia. Morganetta is a dimunitive of Morgan, so here we've got Morgan again as part of a trio. If I'm understanding it correctly, Morganetta and Nivetta are the only ones who play a real role (tempting the heroes sexually), but the author still chose to round them out to three. So it seems that Morgan le Fay has a lot in common with the three Fates of Greek mythology. She appears with two sisters or attendants. Making her the head of nine sisters cubes that. Bibliography

1 Comment

Who was Mordred's wife? Mordred is the son and eventual doom of King Arthur in Arthurian legend. Several retellings give that Mordred had sons of his own, so there must have been a wife or something out there. But her name and identity slips through our fingers. Even her existence is only inferred.

Or is it? In some of the earliest versions, Mordred's wife is Guinevere. Yes, that Guinevere. In the Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain) (c. 1136), Mordred weds Guinevere as part of his takeover. He has Arthur's lands, Arthur's throne, and Arthur's queen. The Historia leaves it unclear how Guinevere felt about this, but later versions varied. She might be happy to comply, or she might flee and barricade herself in the Tower of London. In the Alliterative Morte Arthure (c. 1400), Guinevere even bears children to Mordred - although based on the timeline, these cannot be the grown sons of Mordred seen in other sources. In the romance Escanor (c. 1280), Mordred has an "amie" or love who is a vain and evil maiden. We do not hear her name, or any other details, though. Then there is Hector Boece's History and Chronicles of Scotland (c. 1527). Here, we here of "Modred and his Gude-father Guallanus." Gude-father means father-in-law; thus, Mordred married a daughter of Guallanus or Gawolane. I have seen this name interpreted as Gawaine, Cadwallon Lawhir of Gwynedd, or Caw of Prydyn. This will be important in a moment. Now we get to the big ones: Gwenhwyfach and Cwyllog. Gwenhwyfach or Gwenhwyvach is a woman who appears briefly in the Welsh Triads. When she slapped Gwenhwyfar (Guinevere), one of the "Three Harmful Blows of the Island of Britain," it led to the battle of Camlann, the civil war and final implosion of Arthur's reign. In the early Arthurian work Culhwch and Olwen, Gwenhwyach is briefly mentioned as Gwenhwyfar's sister. Around 1757, a Welsh scholar named Lewis Morris wrote the encyclopedic Celtic Remains, listing many personages from Welsh tradition. He listed Gwenhwyfach as the wife of Medrod (Mordred). He combines the different causes for Camlann, making her Mordred's queen. The quarrel between the two queens (over some nuts, of all things) leads the two kings to battle and ruin. Other writers picked up this tack, as in Thomas Love Peacock's novel The Misfortunes of Elphin (1829). Marrying Guinevere’s quarrelsome sister to Arthur’s evil son at least makes narrative sense. Each tied to the civil war that ends Arthur’s reign, Gwenhwyfach and Mordred are a natural match. It also ties into the idea that Mordred sought to marry Guinevere. Gwenhwyfach's name may be derived from her sister and at one point they may even have been the same character. However, the origin of Gwenhwyfach as Mordred's wife seems to have originated with Morris. There are no older sources or legends to connect the two characters. According to A Welsh Classical Dictionary, the confusion may have arisen over a late version of the genealogy Bonedd y Sant. One of the people listed is Saint Dyfnog, son of Medrod. Medrod is a common alternate spelling for Mordred in these sources. The mother of this Dyfnog is given as Gwenhvawc, daughter of Ogvran Gawr. Only one problem: it's the wrong Medrod. This Medrod is the son of Cawrdaf, not Arthur. True, Mordred was originally just Arthur's nephew, but even before that he would have been associated with Arthur's family, Arthur's sister. But the confusion's not over yet. Lewis Morris returns with... Cwyllog. Remember the daughter of Gawolane? Gawolane was interpreted by some as Caw of Prydyn, who had a bevy of children, including the famous historian Gildas. This would make Mordred and Gildas brothers-in-law. The Mordred/Gildas connection "explained" why Gildas gave an unflattering portrayal of Arthur's successor, Constantine, who killed Mordred's sons. This was the tack Morris took in Celtic Remains. He returned to this idea in his 1760 manuscript of the "Alphabetic Bonedd." But this time, he gave a different identity for Mordred's wife. This time she was Kwyllog or Cwyllog, a Welsh saint. Here is a suggestion of a very different story. Gwenhwyfach was violent and unsympathetic, but Cwyllog’s story holds more tragedy. This wife of Mordred was a holy woman. After her villainous husband's death, she entered religious life, and the parish of Llangwyllog (supposedly built around 605) was named after her. Her feast day is January 7. There are some issues. In 1907, Sabine Baring-Gould recounted this version but remarked that Cwyllog's feast day "does not occur in any of the calendars." In addition, Caw of Prydyn's multitudinous children were listed in Culhwch and Olwen, but Cwyllog is not among them. Cwyllog's name may in fact be a back-formation from the place-name Llangwyllog. The actual saint would be Gwyrddelw - a son of Caw of Prydyn. His feast day falls on January 7 in two existing calendars, that being the date of the local festival for the parish of Llangwyllog. So Cwyllog and Gwenhwyfach are later tie-ins, both of which seem to have originated from the pen of the same 18th-century author. First, Lewis Morris may have seen a genealogy which mentioned a Gwenhvawc who was married to a Medrod and combined that with Gwenhwyfach's connection to Camlann - never mind it was the wrong Mordred. He later revised this, or added a second wife, when he connected Mordred's "gude-father" Gawolane to Caw of Prydyn, and thus to an apocryphal daughter of Caw. In fact, not only is Cwyllog possibly fabricated, but there's nothing to connect Gawolane to Caw. Both explanations are clever, but probably in error. The earliest tradition we have is that Mordred married or sought to marry Guinevere. He may have been connected to stories where Guinevere was kidnapped, or he may have been her lover, a predecessor to the later character of Lancelot. FURTHER READING

Similar Posts There are two famous accounts of how King Arthur won his sword.

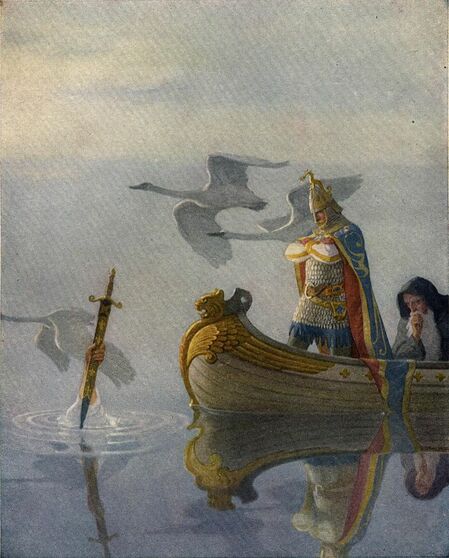

This has led to some confusion. Different sources may use one sword or the other or both. In many works, such as the 1981 film Excalibur and the 1998 miniseries Merlin, the two swords are one and the same. This has caused a reactionary response: these should properly be two different weapons, wielded by Arthur at different times. On a DeviantArt submission in 2006, multiple users bobbed in to remark that Excalibur, the sword from the lake, was not the same as the Sword in the Stone. A 2014 post on StackExchange said much the same thing. The sword in the stone, according to sources like these, is actually called Clarent. Going back to the earliest sources: Arthur's sword in Welsh was named Caledfwlch. This could have developed into Excalibur. That's another debate. Throughout the history of Arthurian legend, Excalibur (or Caliburn, Caliburnus, Escalibor, Chalabrum, etc.) has always been The Arthurian Sword. King Arthur bears it, or one of his champions like Gawaine wields it for him. The Sword in the Stone appears in Robert de Boron's Merlin, but doesn't get a name. In the Vulgate Merlin Continuation, Escalibor is the sword pulled from the stone, which Arthur eventually passes down to Gawain. In the post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin, they are separate swords. The sword from the stone is broken, and Arthur receives Escalibor from the lake as a replacement. The Suite also introduces Excalibur's magical scabbard. In Thomas Malory's Morte d' Arthur, drawing from many Arthurian sources, Arthur draws the sword from the stone. It is not named until Chapter IX, where it's called "Excalibur," shining with "light like thirty torches." This sword eventually breaks, and the Lady of the Lake gives Arthur . . . another sword named Excalibur. Malory's pretty inconsistent throughout this work. It may be that he included Excalibur's name early on by mistake. All the same, here it seems that Arthur had two separate swords and both were named Excalibur. Now for Clarent. Clarent appears in one source: the Alliterative Morte Arthur. It is Arthur's beloved, sacred sword used only in ceremonies and knightings. Arthur views it with reverence and uses his other sword, Caliburn, for battle. Mordred gains Clarent through his treachery and, eventually, slays Arthur with it. There are a few possible sources for the name. In the Estoire de Merlin, Arthur uses the battlecry "Clarent." There was also a city of Clarent in Sorgalles that was part of Arthur's dominion. An interesting similarity exists in the romance The history of the valiant knight Arthur of Little Britain, where a knight named Arthur wins a sword called Clarence. But nowhere else does Clarent appear, and it is never identified as the sword in the stone. It has generally survived as a footnote. In 1895, Selections from Tennyson described it rather dismissively as Arthur's "second-best sword"! However, some Arthurian scholars have taken note of it. In 1960, William Matthews theorized that the Alliterative Morte's two swords were an attempt to reconcile confusing accounts of what swords Arthur used and when. "[I]t seems likely that [Clarent] may be the sword-in-the-stone . . . and that Caliburn is, as usual (though not always), the sword of the Lady of the Lake." Similarly, Kathleen Toohey reviews Arthur's reverential treatment of the sword: "from what we learn of Clarent no better role could have been found for the sword in the stone than the one assigned to Clarent." Note those phrases, though: "It seems likely." "Not always." "From what we learn." "Could have been." Anyone who ties the obscure name Clarent to the sword in the stone is theorizing. It's a valid theory, but still a theory. There's no solid evidence for it. Unhelpfully, for some time there was a Wikipedia article identifying Clarent as the Sword in the Stone. It was nominated for deletion in September 2012. Clarent has gotten a popularity boost in recent years. It's shown as Mordred's sword in the Japanese light novel Fate/Apocrypha (2012-2014). Its origin is very close to that of the canonical Clarent, but I can't find any mention of it being the Sword in the Stone. There are alternate options. Nightbringer, an extensive online Arthurian dictionary, suggests that the sword in the stone could be identified with Sequence, another sword belonging to Arthur, which was borrowed by Lancelot. Alternately, based on romances where Gawaine inherits Arthur's first sword, maybe the sword he wields in Malory - "Galatine" - is the original sword in the stone. (I don't quite follow this, since in those romances the original sword is Escalibor.) These guesses hit the same issues as the Clarent theory: namely, they're guesses. We have a confusion of sources where Excalibur is sometimes the Sword in the Stone and sometimes its replacement. Or, as in Malory, both! Ultimately, the Sword in the Stone cannot be definitively linked to Clarent, Sequence, Galatine, or any of the swords belonging to Arthur . . . except for Excalibur. Sources

Did King Arthur have any children? Most people would probably think only of Mordred, his traitorous son/nephew. It's part of the essential tragedy of King Arthur: he's the greatest king of all time, yet he has no heir to succeed him. Except that in many versions of the story, he actually does have other children. King Arthur's Children: A Study in Fiction and Tradition, by Tyler R. Tichelaar, is the most in-depth look at this subject. It's well worth a read.

In the oldest Welsh sources, Arthur frequently has a son who dies young. Through the centuries, sons of Arthur popped up in romances now and again. Daughters of King Arthur are a much rarer subject, but not totally unknown. Nathalia The medieval legend of St. Ursula recounts how a British princess led eleven thousand virgins on a pilgrimage, only for them all to meet death as martyrs. There have been many retellings - one of them "De Sancta Ursula: De undecim milibus Virginum martirum," usually attributed to a monk named Hermann Joseph writing in 1183. This version gives a prodigious list of names for Ursula's companions. One, mentioned in a single line, is Nathalia, "[f]ilia etiam Arthuri regis de Britannia" (daughter of Arthur, king of Britain). There's very little to go on here. It's hard to say whether this is even the King Arthur we're looking for. The author tosses in a multitude of famous names from many different eras. There are royal names like Canute, Pepin and Cleopatra, and saint names like Columbanus, Balbina and Eulalia. Some of them might be traditionally connected to Ursula, but with others, one feels the author was using whatever names he could think of at the moment. Anyway, a hypothetical historical Arthur would have lived around the late 5th to early 6th century. Ursula's date of death is usually given as 383, way too early. Whatever her parentage, Nathalia is presumably martyred with the rest of the virgins at the end of the story.

Hild In the Icelandic Thidrekssaga, composed in the first half of the 13th century, the titular Thidrek seeks a bride: Hild, daughter of King Artus of Bertangaland (Brittany). She falls in love with Thidrek's nephew Herburt instead. This is really only a footnote in the story and Hild isn't mentioned afterwards. There are other versions of the story, but this is the only one to connect the Hild character to King Arthur. The incident echoes the story of Tristan and Isolde. Artus also has two sons in the Thidrekssaga, named Iron and Apollonius. Iron marries a woman named Isolde and has a daughter of his own, also named Isolde, who would be Arthur's granddaughter.

Grega From the 14th century Icelandic Samsoms Saga Fougra (Saga of Samson the Fair). King Arthur of England and his queen, Silvia, have a son named Samson and a daughter named Grega. Unlike her brother, Grega is mentioned only once, when she's named in the introduction. This is, however, King Arthur in name only. There's nothing to connect it to Arthurian canon except that it includes the Arthurian motif of the magical chastity-testing mantle.

Emaré A 14th-century Breton lai. Emaré is the daughter of a great emperor named Artyus and his late wife Erayne. Artyus is "‘the best manne / In the worlde that lyvede thanne," but he's also temporarily stricken with lust for his daughter, like the king in Donkeyskin. The story is peopled with names from Arthurian legend. Artyus is a form of "Arthur." Tristan and Isolde are mentioned as an example of famous lovers, and other characters have names like Kadore and Segramour. Erayne is reminiscent of Elaine or Igraine. "Emare" is really not an Arthurian story, though. It takes place in France and Rome. Emare marries the king of Galys, which could be Wales but is more likely Galicia in Spain. There is a distinct lack of England. The names are probably intentional references which set the stage and put readers in mind of Arthurian settings. This was common in many lais. The connections are interesting, but I would consider this the wrong Arthur.

Archfedd, Archvedd, Archwedd In the Welsh genealogical tract Bonedd y Saint we get this line: "Efadier a Gwrial plant Llawvrodedd varchoc o Archvedd verch Arthur i mam" (Efadier and Gwrial, children of Llawfrodedd the knight and Archfedd daughter of Arthur, their mother) This is the only appearance of Archfedd, and it’s unclear if her father is the Arthur. On the other hand, Llawfrodedd is one of Arthur’s warriors in Culhwch and Olwen and The Dream of Rhonabwy. Also apparently he had a really nice cow. The “Bonedd y Saint” genealogy was compiled in the 12th century and the earliest example survives from the 13th. However, Archfedd is a later addition from manuscripts written from 1565 to 1713. Many of these manuscripts were copied from each other.

Seleucia The Portuguese novel Memorial das Proezas da Segunda Távola Redonda (Memorial of the Deeds of the Second Round Table), by Jorge Ferreira de Vasconcelos, was first printed in 1567. Here, Sagramor Constantino (a combination of Sir Sagramore and Arthur's canonical successor Constantine) takes the throne after Arthur's death. He marries "infante Seleucia que el rey Artur ouve em Liscanor filha do conde Sevauo sua primeyra molher" - the princess Seleucia who King Arthur [begat?] on Liscanor daughter of Count Sevauo, his first wife. It seems Liscanor died in childbirth. The author didn't pull those names out of nowhere. In the Vulgate cycle, Lisanor is the daughter of Count Sevain and the mother of Arthur's illegitimate son Loholt. Similarly, in Thomas Malory's Morte d'Arthur, Lionors, daughter of Sanam, is the mother of Arthur's illegitimate son Borre. This would make Seleucia the full sister of Loholt and/or Borre. However, she was born in wedlock and is Arthur's legitimate heir. Guinevere (or Genebra in this version) is conveniently removed from the scene when she dies in childbirth with Sir Lancelot's twins, Florismarte and Andronia. Many other second-generation knights appear around Sagramor Constantino's resurrected Round Table. It's rare enough for stories to include Arthur's daughters. Seleucia is particularly rare in that she succeeds Arthur's throne. Sagramor and Seleucia may even have their own child - near the end, they appear accompanied by a Princess Licorida who is eight years old. Unfortunately, I do not know of any English translations. Baedo (Badda, Baddo, Bado, Bauda, Badona) Baddo was the wife of the Visigothic Spanish king Reccared. She was present at the Third Council of Toledo, 589. She was not Reccared’s first wife. Their son was Suintila or Swinthila (ca. 588-633). Little else is known about her. Almost a thousand years later, in 1571, Esteban de Garibay y Zamalloa’s Compendio Historial described her thus: "Badda, dizen, auer sido hija de Arturo Rey de Inglaterra" (Badda, they say, was the daughter of Arthur, King of England). Other Spanish and Portuguese manuscripts followed suit, many of them quoting Garibay. Differing sources call her father Fontus (Annals of the Queens of Spain). The link to Arthur may have been drawn because of the similarity of her name to the Battle of Badon, one of the battles historically associated with Arthur. If nothing else, Queen Baedo could have lived in the same century as an Arthur who fought at Badon, if a bit late to be his daughter. Tortolina, Tortlina Sir Thomas Urquhart's Pantochronachanon (1652) says Arthur had a daughter named Tortolina, who married a man named Nicharcos and begot a son named Marsidalio born in 540. This work traces Urquhart's family tree back to Adam and Eve and is probably intended as a parody. Sir Laurence Gardner in Bloodline of the Holy Grail (1996) says with no sources that Tortolina was actually Mordred’s daughter. Melora, Mhelóra The Irish “Mhelóra agus Orlando” has survived in three manuscripts dated between the 17th and 18th centuries (one manuscript is dated 1679). Melora is Arthur and Guinevere's daughter who falls in love with Orlando, the prince of Thessaly. When he is enchanted by his rival, Melora disguises herself as the Knight of the Blue Surcoat and travels the world to save him. This romance includes strong fairy-tale elements. It might have been influenced by Ariosto's epic Orlando Furioso (which also features a maiden knight) or by another Irish romance, The Tragedy of the Sons of Tuireann (with its globe-trotting quest for magical objects). Melora is one of the more well-known daughters of Arthur, but still deserves much more attention.

Huncamunca Arthur and Queen Dollalolla's daughter in Henry Fielding's "Tom Thumb" (1730). This satirical play features nonsense names and comically tragic deaths. Gyneth The warrior daughter of Arthur with the fairy queen Guendolen, in Sir Walter Scott's The Bridal of Triermain (1813). Merlin casts her into a magic sleep until her true love awakens her centuries later. (Incidentally, Geneth is also a Welsh name meaning "girl.") Burd Ellen In the fairytale Childe Rowland, first published in 1814, King Arthur has four children including Rowland and a daughter named Ellen. I've written about Childe Rowland and its dubious ties to Arthurian canon here. Basically, the collector of the tale heard a version that included Merlin, and added in Arthur, Guinevere and Excalibur himself. Iduna The daughter of Arthur and Ginevra (Guinevere) in “Edgar,” a dramatic poem in five acts by Dr. Adolph Schütt, published in German in 1839. The play evidently takes place during the time of the Heptarchy, the seven kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England from the 5th to 10th centuries. Arthur is king of the Silures (an ancient British tribe settled in southeast Wales.) Edgar is an English prince, unjustly banished, who becomes a knight of the Round Table and falls in love with Princess Iduna. Although she returns his affections, her father has promised her to whichever knight accomplishes the mightiest task. Iduna is apparently an only child, as the aged Arthur is anxious for her to marry a man who will make a good king. Edgar marries her by the end of the play, of course. A rather scathing review (from what I can tell via Google Translate) calls the five acts "building blocks to a temple for the god of boredom."

Princess Poppet Apparently, a daughter of Arthur named Poppet appeared in the 1853 pantomime "Harlequin and Tom Thumb; or, Gog and Magog and Mother Goose's Golden Goslings." Like Huncamunca before her, she fell for Tom Thumb.

Tryphine’s daughter Saint Tryphine is the subject of a Breton legend with similarities to the story of Bluebeard. Usually, her husband's name is Conomor, and Tryphine and her son Tremeur are venerated as martyrs. In 1863, folklorist François-Marie Luzel collected a mystery play with eight acts, in which Tryphine is merged with Guinevere as the wife of King Arthur. This is not the Bluebeard-style legend. The villain of the story is Tryphine's brother Kervoura, who sets out to remove Arthur’s legitimate heirs so that he can inherit the kingdom. First he kidnaps Tryphine’s newborn son and accuses her of infanticide. Arthur is about to have her executed, but she survives in hiding for six years, until Arthur accepts her innocence and takes her back. She gives birth to his daughter. Kervoura’s still at it, though, and frames Tryphine for adultery. Fortunately, her son has survived and exposes the truth just before she can be executed. The boy might be named Tremeur, but that name isn’t used. When he returns to the narrative, he is referred to only as “the Malouin,” or inhabitant of Saint Malo, where he was secretly raised. Arthur and Tryphine’s daughter is mentioned in the sixth act and disappears for the rest of the play. I don’t think she gets a name. Her birth enforces that Arthur is still in need of a male heir, and gives Kervoura a chance to gain Arthur’s confidence moving into the final act. It ends with the villains punished and the royal family of Arthur, Tryphine and the Malouin reunited. In this scene of family unity, it’s strange that the youngest child isn’t mentioned. One wonders whether she died or whether, since the crown prince has returned, she’s simply not important. There’s also the possibility that the daughter appeared in some productions despite not being mentioned in Luzel's transcript.

Blandine In Jean Cocteau's 1937 play, Les Chevaliers de la Table Ronde, Guinevere has a son and daughter named Segramor and Blandine. Arthur believes they are his. Segramor is actually Guinevere's son with Lancelot. Blandine, the fiancee of Gauvain (Gawaine), is evidently Arthur's biological daughter. When searching for daughters of Arthur, it can be easy to stumble across daughters of the wrong King Arthur. In some of these examples (e.g. Emare or Grega), the authors are simply borrowing names and motifs from Arthurian tradition to craft original stories. On the other hand, there are stories like Melora's or Seleucia's. There could be other works which give Arthur a daughter, but which haven't come to light yet. That may be because they're too obscure or because they're written in other languages. I hope to see translations of such works in the future. And with modern retellings, daughters of Arthur have made more frequent appearances than ever before. The Scottish tale of Childe Rowland was first published by Robert Jamieson in 1814. This tale follows the children of King Arthur - specifically, a son called Child Roland and a daughter called Burd Ellen. (Child and Burd are noble titles for a knight and lady.) The King of Elfland steals Burd Ellen, and one by one her brothers seek her. The two oldest never return from Elfland. Roland, the youngest, goes to Merlin for advice, then fights his way into the otherworld with his trusty claymore. There he finds his sister, who offers him food, but he remembers Merlin's wisdom and refuses to eat. The elf king arrives, chanting, "With a fi, fi, fo, and fum! I smell the blood of a Christian man!" Roland fights him to a standstill and forces him to resurrect his two brothers, killed trying to save Ellen. The elf king anoints them with red liquid from a crystal phial and brings them back to life. With that, the four siblings proceed home.

Jamieson heard the story from a tailor at age seven or eight, and reconstructed it years later. He mentions that he left out some details because he wasn't sure of his memory. He added in the names of Arthur, Guinevere, Excalibur, and the location of Carlisle, based on the fact that Merlin appeared in the story. Although the story as Jamieson tells it can only be dated to the early 1800s, there is evidence of the story being older. For one thing, Rowland's name appears in Shakespeare's King Lear (1606). The line is spoken by Edgar, posing as a mad fool who rambles only nonsense. Child Rowland to the dark tower came, His word was still,--Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man. This is echoed in Jamieson's version with the "fi, fi, fo, fum" chant; Jamieson said that it was one of his most enduring memories from hearing the tale for the first time. Later, the folktale collector Joseph Jacobs published a retelling which called the King of Elfland's dwelling the "Dark Tower," drawing on the King Lear verse. Previously, other readers believed that the nonsense verse might be a mix of references - for instance, "Childe Roland" might be from the eleventh-century French poem Song of Roland, and the "fie, foh and fum" from "Jack the Giant-killer." Jamieson presented an alternative: the Scottish story of Childe Roland. This all began in his 1806 collection Popular Ballads and Songs. In the first volume, he described three Danish ballads about a character named Child Roland. He gave the first of these ballads in the second volume of Popular Ballads, and the second two in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, along with his retelling of the English version. From the very beginning, Jamieson was focused on that one line in Shakespeare - more on that later. The Danish ballads came from the 1695 work Kaempe Viser or Kæmpevise. It's not clear whether any of them appeared in the original, shorter edition of 1591, and I have not been able to locate a copy of either, so I have to base my knowledge on Jamieson's translation. In the first, the main characters are an unnamed youth and Svané, the children of Lady Hillers of Denmark. The second has Child Roland and Proud Eline (no parentage given), and the third has Child Aller and Proud Eline (children of the king of Iceland). The second version is the longest and most dramatic, and uses nearly the same names as Jamieson's Scottish tale. In all three ballads, the villain is a monstrous giant or merman known as Rosmer Hafmand, who dwells in a castle beneath the sea. Roland (or Aller) sets sail in search of his sister and reaches Rosmer's castle after his ship sinks. He enters the castle as a spy and lives there for some time. In the second version, Roland and Eline begin an incestuous relationship and Eline becomes pregnant. In these ballads, there is no daring battle between Roland and his sister's abductor; instead, he pretends he's leaving, packs his sister in a chest, and asks Rosmer to carry it for him. He rescues the captured maiden through trickery instead of combat. Jamieson and others argued that Childe Rowland was an ancient English tale which spread to Denmark. This was Jamieson's pet theory which he was pushing very hard. Besides King Lear, there are a couple of older works with plots similar to "Childe Rowland." In The Old Wives' Tale, a 1595 play by George Peele, there are multiple plot threads and fairytale references. The most relevant plot thread deals with two princes searching for their sister, stolen away to the sorcerer Sacrapant's castle. (All of the names are from the Orlando Furioso). They are aided by an old man (similar to Merlin) but eventually all three siblings are rescued by another party. Similarly, in the masque Comus, first presented in 1634, the necromancer Comus steals away an unnamed lady to his palace, where he tries to entice her to eat the food he offers. She holds out until her brothers arrive to rescue her. Even then, the lady can only be freed by touching her lips and fingers with a magic liquid, similar to the ointment which resurrects Roland's brothers. The similarities are clear and have been pointed out by various writers. So we know that:

Some writers have tried to strengthen the tale's ties to King Arthur, but I think this is a mistake. Roger Sherman Loomis, in Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance, suggests that Child Rowland "seems to go back through an English ballad to an Arthurian romance" and is ultimately derived from the 8th- or 9th-century Irish tale of Blathnat. Blathnat, the lover of Cuchulainn, is abducted by a giant named Curoi. At least two Arthurian romances include this sequence of events: De Ortu Waluuanii (The Rise of Gawain), with the villain as the dwarf king Milocrates, and The Vulgate Lancelot with the villain being the giant Carado. Although the characters vary, the story remains the same: a maiden is abducted by a being who can only be slain by one weapon. Her lover sneaks into the being's fortress to rescue her. The damsel steals the weapon and gives it to her lover, who beheads the villain. This is the family of tales to which Loomis tried to tie Childe Rowland. However, the only thing they really share is the motif of the abducted maiden's rescue. That motif is incredibly widespread through many different tale types. I would say Childe Rowland bears more resemblance to "Sir Orfeo" (a middle English retelling of the myth of Orpheus) than it does to Blathnat's story. In addition, Loomis' theory ignores that "Childe Rowland" is a reconstruction and that Arthur and Guinevere were added in based on a single mention of Merlin. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Culhwch and Olwen is a Welsh tale which dates to the 11th or 12th century. It makes up one of the sections of the Mabinogion, a collection of some of the oldest existing Welsh literature. The story follows Culhwch, a cousin of King Arthur, who falls in love with a woman named Olwen. Her father will only let her marry if Culwhch completes impossible tasks and brings him a series of marvelous gifts. For help, Culhwch turns to King Arthur and his warriors.

This story provides one of the earliest looks at the mythology of King Arthur. There are all sorts of things that never made it into the later Arthurian mythos. One thing that always intrigued me was the mention of Rhymhi and her pups, Gwyddrud and Gwydden Astrus (or Gwydrut and Gwyddneu Astrus). First off, the cubs are listed among Arthur's warriors. Later, however, finding Rhymhi and her pups is one of the tasks Arthur's warriors must complete. Said Arthur, "Which of the marvels will it be best for us now to seek first?" "It will be best to seek for the two cubs of Gast Rhymhi." "Is it known," asked Arthur, "where she is?" "She is in Aber Deu Cleddyf," said one. Then Arthur went to the house of Tringad, in Aber Cleddyf, and he inquired of him whether he had heard of her there. "In what form may she be?" "She is in the form of a she-wolf," said he; "and with her there are two cubs." "She has often slain my herds, and she is there below in a cave in Aber Cleddyf." So Arthur went in his ship Prydwen by sea, and the others went by land, to hunt her. And they surrounded her and her two cubs, and God did change them again for Arthur into their own form. This raises a ton of questions. Has Arthur just picked up a family of werewolves? The tale is full of redundancies as well as spots where scenes have apparently been placed in the wrong order. Some of the warriors mentioned in Arthur’s court are only collected much later in the tale. Finding the two whelps of Rhymhi was probably one of the impossible quests demanded by Olwen’s father, as resources for an evil-giant-pig hunt. However, it seems their names were left out of the actual list of quests. Olwen’s father does mention that the heroes need the beard of Dissull Varvawc to make a leash for “those two cubs,” and the huntsman Kynedyr Wyllt to hold them. This is presumably where Rhymhi’s cubs would have originally fit into the list. The beard-leash is later claimed for a different dog, Drudwyn, even though Drudwyn’s leash was supposed to be a completely different quest. It’s very confusing. Maybe they didn’t need the leash because God transformed Rhymhi’s pups into their own form? On the other hand, other pairs of dogs are mentioned, so Rhymhi's cubs might not have been the intended recipients of the beard-leash after all. Best to start at the beginning. Who is Rhymhi? Her true shape is never specified. Neither do we know why she was in wolf form. The only information we get is that Arthur had to specifically ask what form she had taken - so was she a shapeshifter? Finally, divine intervention is required to restore her to her real self. The meaning of her name is unclear. It looks similar to the Rhymni or Rhymney, a river which flows through Cardiff. That word may come from "rhymp" for a bore, as the river bores through the land. Most of the explanations floating around indicate that she was a human princess punished by God for her sins. This apparently stems from Archaeologia Cambrensis, Volume 2 (1856): “On the Names of Cromlechau” by T. Stephens. The author lists a number of cromlechau (stone structures) with names all having to do with female greyhounds and wolves. Seeking the “vilast” or “milast” mentioned in so many titles, the author seizes on Gast Rhymhi, who was a “bleiddast” or she-wolf. Another cromlech was known as Llech y Gamress, the stone of the princess or giantess. All that’s known about Rhymhi was that she was female, possibly of some importance, and God restored her from her wolf form to her true form. Stephens suggests that this indicates the “princess” of Llech y Gamress was Rhymhi in her human form, and draws a connection to other mythical animal transformations, especially the legend of Melusine. Milast connects to Melusine. The words fleiddast and ast connect to bleiddast. Rhymhi has two cubs, and Melusine (in some versions) has two sons with her husband Raymond. Therefore Gast Rhymhi is the she-wolf of Raymond, and that’s how all those cromlechau got their names. This is a significant leap depending mainly on similar names - a dangerous path for reconstructing myths. Melusine has any number of children depending on the myth. More importantly, she's not connected to wolves in the slightest. She turns into a half-serpent creature. However, Stephens' conclusion may have something to it. If Rhymhi is like most of the transformed animals in the Mabinogion, it seems likely that she was originally a human woman and possibly royalty. Human-to-animal transmogrification is a huge theme in these stories - sometimes through intentional shapeshifting, but more often for revenge and punishment. Specifically within Culhwch and Olwen, the kings Nynniaw and Pebiaw are turned into oxen. Another king, Twrch Trwyth, becomes a monstrous boar. All are receiving divine punishment for their sins. Like Rhymhi, Twrch has children - seven little pigs - who share his curse. One of Arthur's knights who can speak all languages communicates with the pigs, who mention being "turned . . . into this form." This indicates that they are also men being punished for wrongdoing. Again, animal transformations are common in the Mabinogion and in Welsh and Irish literature. In the Mabinogion, you have Gwydion and Gilfaethwy, another set of brothers with alliterative names. For the crime of rape, they are temporarily transformed into a mated pair of deer, then pigs, then finally wolves, before they and their animal offspring are restored to humanity. (Gwydion is a scheming, tricksterish figure. His name is from the same root word as Gwydden. Could here be a connection to Gwydden Astrus, “Cunning Gwydden”?) “Gwyddien Astrus” also appears in the genealogical tract Bonedd yr Arwyr, as the son of Deigr. Outside the Mabinogion, Bran and Sceolan were the hounds of the Irish hero Finn. They were also his cousins, born in several versions while his aunt was turned into a dog by a jealous rival. There are other tales connecting King Arthur to werewolves, such as Melion or Arthur and Gorlagon. Phillip A. Berhardt-House suggested there might be an older corpus of tales where Arthur goes seeking a family of werewolves for help in a hunt. Finally, there is one other occurrence of Rhymhi's story - probably. The poet Iolo Goch (c. 1320 – c. 1398) wrote an ode to Saint David, or Dewi, of Wales. Here there appear two brothers, Gwydre Astrus and Odrud (or Gwydro Astrus and Godrud). For some unspecified sin, God has turned them into wolves. Their mother has also been cursed. St. David miraculously frees them from their wolf forms. God transformed, harsh angry rage, two wolves of devilish nature, two old men who were from the land of magic, Gwydre Astrus and Odrud, for committing, evil exploit long ago, some sin which they willed; and their mother – why should she be? - was a she-wolf, a curse on her; and good David released them from their long suffering in their exile. (Translation source: Seintiau) This myth does not appear anywhere else in connection to St. David, but plenty of scholars have spotted the similarity to the Mabinogion and Rhymhi's cubs. The Lives of the British Saints suggests that “wolf” is a metaphor for outlaw, and that there is a rationalist explanation - St. David simply forgave these men’s crimes and accepted them back into society. However, I think Iolo Goch and the writer of Culhwch and Olwen drew on the same now-forgotten myth. A mother and her two sons are turned into ravenous wolves for some transgression, and God restores them via the main character (King Arthur or St. David). Although there seems to be a connection to stories like Bran and Sceolan, there is a problem with that theory. It is not clear whether Rhymhi gave birth in wolf form. And if she is parallel to the other transformed monsters which Arthur hunts, she was probably transformed for a crime, not because a jealous fae cursed her. In the story of St. David, the focus is on the two wolf-brothers, who are "old men" cursed for their sins, not simply born under a curse. To me, it seems more likely that Rhymhi's cubs were, like Twrch Trwyth's piglets, originally human. There is still plenty of room for interpretation; as Bernhardt-House says, "it is unclear . . . whether Rhymhi was a transformed human . . . a magical person of some sort who could change shapes, a famous hound, or some combination of all of these." (p. 219) I loved Lorna Smither’s story "Rhymi," which takes full advantage of that ambiguity. SOURCES

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed