|

I first saw the news about this book being published a while ago and knew I had to pick it up. Issunboshi by Ryan Lang is an “epic graphic novel retelling” of the Japanese fairytale of Issunboshi, one of the most famous versions of ATU type 700. The publishing and printing were funded through Kickstarter. It took a while to get my hands on a copy, but here we are!

This retelling gives Issunboshi a more elaborate backstory. The gods used the Ame No Nuhoko, the Heavenly Spear, in the creation of the world. Afterwards, the spear was broken into four parts: the shaft, mount, blade, and spirit. One day an oni came across a piece of the spear. Gaining its power, he began collecting the other pieces and gathering a demon army with the goal of conquering the entire world. The spirit of the spear, searching for a way to stop things, found a childless couple who wished for a son even if he was only as tall as a thumb. The spirit took physical form as the tiny son they wished for, and they named him Issunboshi. The story proper starts with Issunboshi, now a young man six inches tall, living with his parents in their village. Although tiny, he’s stronger than most ordinary humans, and segues between riding on a pet owl or toting heavy buckets around. The story sets up Issunboshi’s feelings of inadequacy (he is approximately as tall as a toothbrush, after all) and his parents’ steady encouragement that he can be great. Then Issunboshi is kidnapped by a tengu or crow demon. Finding himself in the monster-haunted wilderness with only his old needle-sword for protection, he is rescued by a group of warriors who fight monsters and are preparing for a war against the Oni. Issunboshi’s new mentor tells him of his true past and begins training him for an epic confrontation. Issunboshi, small as he is, is the only one who can stop the oni from bringing on an apocalypse. This was a quick read with a simple, straightforward story. There are no big surprises from the plot, and characters don’t get a ton of depth or development. It’s tropey, or archetypal, or whatever you want to call it. There was some comic relief, but the jokes didn’t really land much. I did have a minor quibble with the theme. The book’s message, stated very clearly several times, is that even someone small can do great things (like save the world, fight a giant monster in a hand-to-hand battle, etc.). Although Issunboshi is small, he has near-godlike powers. His mentor tells him immediately that he’s the key to defeating the oni. Training montages and a stumble on the journey help offset this, but still feel quick or even rushed (a larger issue with the middle of the story, between a good beginning and ending). The message comes across okay, but it might have hit harder if Issunboshi wasn’t the amazingly strong incarnation of an all-powerful weapon, but just… a little guy. Ryan Lang is an animator and visual development artist who's worked at Disney and Dreamworks, and you can see that style strongly in his art here. Although everything is in grayscale, the characters are all very vibrant and expressive with unique designs. It also feels very cinematic, and the panels and word bubbles aren't always very dynamic, leaving the effect of storyboards or screenshots from an animated film. However, it is very pretty. There are lots of full-page splashes and spreads, showing off beautiful art. The book is advertised as epic, and it definitely pulls that off. The fairytale of Issun-boshi stands out among thumbling stories; it’s a coming-of-age tale, where Issun-boshi moves out of his parents’ home, finds a wife, and literally and metaphorically grows up—unlike most Western thumbling narratives, where the hero remains a child. I would say that Issun-boshi is, narratively speaking, one of the strongest and most compelling examples of ATU 700. Lang's graphic novel keeps the coming-of-age theme, but is focused on Issun-boshi’s clash with the oni. Instead of a chance encounter near the end of the story, this is a battle Issunboshi was always destined for. The book includes some pieces of concept art at the end, including one that looks like early drafts might have skewed closer to the original fairytale, with Issunboshi meeting a young noblewoman. There’s no romance or equivalent to that character in this retelling. Another big difference is replacing the magic hammer (uchide no kozuchi) of the fairy tale with the spear from an unrelated Shinto creation myth. There are echoes of some typical thumbling motifs, such as when Issunboshi is carried off by a bird or rides on a horse’s head. Overall, it was great to see a new adaptation of one of my favorite thumbling stories. While the story could be stronger, it’s still enjoyable and the art is fantastic. Definitely worth checking out. Further reading

0 Comments

You may have heard of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but have you ever heard of Svend Tomling?

Svend Tomling is the third oldest surviving thumbling tale, and is largely forgotten other than a few footnotes. Interestingly, its more famous predecessors, the Japanese Issun-Boshi and English Tom Thumb, are both fairly unique among thumbling tales. Issun-Boshi is one of the short stories and fairytales known as the Otogizōshi, written down mostly in the Muromachi period from 1392-1573. The exact date of Issun-Boshi's origin is unclear, but it's usually assigned to the 15th or 16th century. Japanese thumbling tales make up a unique subtype, with similarities to The Frog Prince. "Issun-boshi" is a romance in which a tiny, unassuming hero wins a princess for his bride, and then transforms into a handsome prince. The story still contains classic Thumbling motifs, and the story is surprisingly close to that of Tom Thumb all the way over in England. Issun-Boshi is born to an elderly couple who pray for a son; he uses a needle for a sword; he leaves home to serve an important nobleman. An oni, or demon, tries to swallow him, but Issun-Boshi escapes from his mouth alive. Tom Thumb is also of unclear original date, but at least we have dates for some important pieces of evidence. His name is mentioned in literature as early as 1579. A prose telling of the tale was printed in 1621, and a version in verse in 1630, although these are dated to the printing of the individual copy, not to the date of composition. The prose and metrical versions are very different, but hit most of the same beats. A childless couple turns to the wizard Merlin for help. Their son, who is born unusually quickly and of tiny size, wields a needle for a sword. He is swallowed in a mouthful of grass by a grazing cow, cries out from its belly, and is excreted. A giant tries to devour him. He is swallowed by a fish and discovered when someone catches it to cook it. He goes on to serve in King Arthur's court, then falls sick. Here the two editions diverge - the metrical version has him die of his illness and be grieved by the court, but the prose version has him recover when treated by the Pygmy King's personal physician, and go on to have other adventures including fighting fellow literary character Garagantua. Both of these stories are clearly thumbling stories, but they do not fit the usual map of Aarne-Thompson Type 700, a formulaic tale found consistently through Europe, Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. The Grimms were aware of this formula and actually published two thumbling stories. Their first was Thumbling's Travels, also a rather unusual example, but they later went back and added Daumesdick (Thumbthick, also translated as Thumbling), which better fit the pattern. A childless couple wishes for a son; he is only a thumb tall; he drives the plow by riding in the horse's ear, is sold as an oddity, escapes, has an encounter with robbers, is swallowed by animals, and finally returns home. Issun-Boshi, again, is part of a unique subtype. As for Tom Thumb, it's likely the subject of some literary embellishment, expanding a simpler traditional tale. Hints of the wider tradition peek through, like a scene where Tom returns home with a single penny and is welcomed by his parents. This is where many Type 700 stories end, but Tom Thumb instead keeps going. The traditional tale started really getting attention with the Grimms, but they were not the first ones to publish an example. The earliest surviving specimen is the Danish "Svend Tomling", or Svend Thumbling. Svend is a common men's name meaning "young man" or "young warrior," giving it the same generic feel as "Tom" in English. Both Svend Tomling and Tom Thumb essentially boil down to the same name of "Man Thumb," the way the name Jack Frost boils down to "Man Frost." Svend Tomling appears to have been the generic name for a thumbling in Denmark; it was also used for a Hop o' My Thumb type, which is an entirely different tale. The relevant version is a 1776 booklet by Hans Holck. It drew attention from the Danish historian Rasmus Nyerup, and from the Brothers Grimm. Nyerup, in particular, remembered reading or hearing the story as a child. The translation I've been working on is admittedly choppy, and I take responsibility if it's in error. "Svend Tomling" begins, as most thumbling stories do, with a childless couple. The wife goes to visit an enchantress and, upon instruction, eats two flowers. She then gives birth to Svend Tomling, who is born already clothed and carrying a sword. The section that follows is almost exactly the classic thumbling tale, with some unique details. Svend helps out on the farm by driving the plow, sitting in the horse's ear. A wealthy man witnesses this, purchases him from his parents, and carries Svend away (specifically, keeping him in his snuffbox). Svend escapes. Falling off their wagon, he lands on a pig's back and begins riding it like a horse. However, he is attacked by wild animals, and eventually the pig runs away. Lost in the middle of nowhere, Svend overhears two men plotting to rob the local deacon's house and asks to come along. He makes so much noise that he awakens the servants, and the thieves flee. There is a small divergence here, where the house owners think that Svend is a nisse (a Danish house spirit similar to the brownie) and leave out porridge for him. It doesn't take long before Svend is accidentally swallowed by a cow eating her hay. He calls out from inside her stomach to the milkmaid, who is frightened and thinks the cow is bewitched. Here's another divergence: people take this to mean that the cow can foretell the future, and flood to visit. This introduces a long monologue from a priest complaining about the peasants. Ultimately the cow is slaughtered. A sow eats the stomach in which Svend is still trapped, then poops him out. He falls into the water, where his own father happens to hear him crying out for help, and takes him home to recover. So far the plotline has been generally typical, but at this point, the story strikes out in its own direction. Svend announces that he wishes to take a wife. In particular, he wants to marry a woman three ells and three quarters tall. The length of an ell varied by country, but in Denmark, it was considered 25 inches. Svend Tomling is speaking of a wife who would be something like seven feet tall. His parents try to dissuade him, saying that he's far too small, and Svend grows frustrated. He begins bothering a "Troldqvinden" (a troll woman or witch) until she gets angry and transforms him into a goat. His horrified parents beg her to have mercy, and she relents and changes him into a well-grown man. The rest of the booklet (four pages out of the whole sixteen!) deals with Svend and his parents discussing his future, with questions of choosing an occupation and a bride, as he sets off into the world. Rasmus Nyerup took a pretty dim view of this story, remarking that great liberties had been taken with the folktale he remembered - particularly the priest's long speech about the problems with peasants, which has nothing to do with Svend Tomling. I suspect that the disproportionately long section on life advice is also original. The motif of eating two flowers and then giving birth to an unusual child is striking. This is exactly what happens in the story of King Lindworm (also Danish), where the resulting child is a lindworm and must be disenchanted. Also in Tatterhood (Norwegian), the queen who eats two flowers gives birth to a daughter, just as precocious as Svend, who rides out of the womb on a goat and carrying a spoon. Tom Thumb is usually listed as an influence on Hans Christian Andersen's Thumbelina. However, I think Svend Tomling might have been a stronger influence. If Rasmus Nyerup heard the story as a child, Andersen might have too. Both Svend Tomling and Thumbelina begin with a childless woman visiting a witch for help. Svend's mother eating flowers to conceive hearkens to Thumbelina being born from a flower. Both Svend and Thumbelina focus on the question of the character finding a fitting mate and a society that they fit into. Svend, like Thumbelina, is faced with incompatible mates, although for him these are ordinary human women, and for her, talking animals. Ultimately, otherworldly intervention transforms them to fit into their preferred society. Svend goes to a troll woman who makes him tall enough to seek a bride, while Thumbelina marries a flower fairy prince and gains wings like his. (Actually, Issun-Boshi did this too, getting a magical hammer from an oni and growing to average height.) Overall, Thumbelina has more in common with Svend Tomling and even Issun-Boshi than she does with Tom Thumb. The story itself is not all that great, but it does provide one of our earliest examples of the Thumbling story - and casts light on the others that followed. Sources

I've been thinking about how in several different tales, a Thumbling figure becomes a favored servant of a king.

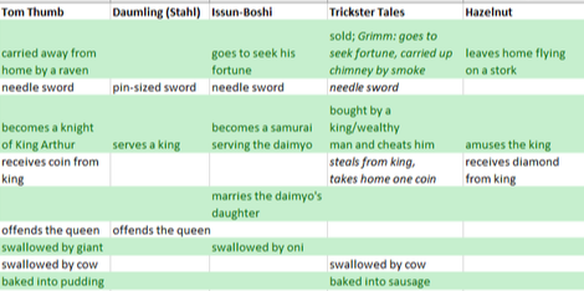

Tom Thumb becomes King Arthur's dwarf and one of his favored knights. (In later versions, he runs afoul of the queen.) Issun-boshi acts as a samurai for a daimyo, or feudal lord. The Hazel-nut Child, in a tale from the Armenian people of Romania, Transylvania and the Ukraine, makes his way to the palace of an African king. Like Tom Thumb carrying home a coin for his parents, the Hazel-nut Child brings home a diamond given to him by the king. Karoline Stahl (the same woman who wrote the first version of Snow White and Rose Red) wrote a story called Däumling. Daumling goes to live in the palace, where he serves the king and several times defends him from assassination attempts. The story was probably inspired by the British Tom Thumb. Both stories have an emphasis on the main character's clothing and needle- or pin-sized sword, as well as an evil queen. Sometimes the thumbling's encounter with the king isn't quite so pleasant. In numerous tales, the thumbling is out in the field with his father, when a rich man, sometimes a noble or king, sees him and asks to buy him. The thumbling sells himself and then runs away, cheating the rich man. In one version, Neghinitsa, the main character does not run away, but ends up working as a king's royal spy until his death. In other stories, like the German "Thumbling as Journeyman," or the Augur folktale "The Ear-like Boy," the Thumbling becomes a robber and a king is one of his victims. In a tale from Nepal (printed in German), the thumbling steals items from the king's palace and eventually wins the hand of one of the princesses. Also in "Thumbling as Journeyman," the little thief takes a single kreuzer, stolen from the king's treasury, to give to his parents back home. Here again is the same motif as Tom Thumb, where the tiny knight asks King Arthur for permission to take one small coin to his parents. In other stories, Thumbling marries the king's daughter - a common ending for fairytales. Issun-boshi marries the daimyo's daughter. In the Philippines, Little Shell and similar characters pursue the daughter of a chief. (See blog post.) In India, Der Angule completes many tasks for a king and finally marries the princess. Some retellings of Tom Thumb, such as Henry Fielding's play, have him woo a princess. I worked a little bit on a chart comparing some of these stories. I included the Grimms' Thumbling among "trickster tales." EDIT: Now with new and improved chart! A study of early Tom Thumb variants reveals a tale about a boy in weird predicaments, mostly involving pudding. He may even have been a kind of spirit or fairy originally.

However, the Japanese counterpart, Issun Boshi, is a romance: the tale of a less-than-impressive man, who manages to marry a woman far above his social stature. It's been compared to the tales of Lazy Taro (whose laziness makes him unappealing) and Ko-otoko no soshi (The Little Man, who is only about a foot tall). In Jane Kelley's Analyzing Ideology in a Japanese Fairy Tale, she goes very in-depth on modern retellings of Issun-Boshi. The hero is raised by parents who adore him even though he's tiny. He eventually falls in love with a princess, rescues her from an oni, and grows to full size with the use of the oni's magic hammer. However, the "official" version that emerges through her article may not represent the original version of the story. It's impossible to say what the original version was. There are many variants with different names. However, the Japanese Wikipedia article indicates that the original version was a little more adult. In the Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folktale (1948), the first tale listed under "Issun Boshi," the one with the longest and most detailed entry, is Mamesuke (Bean Boy). He's born from a woman’s thumb and at seventeen is only the size of a bean. He goes and finds work, and there's a scene where he hides under a wooden clog. He works for a winemaker with three daughters. To trick his way into getting a wife, he smears flour on the middle daughter’s lips while she sleeps. Thinking she's stolen his food, the family agrees that he can take her home. She tries to drown him in the bathtub, but instead of dying, he becomes a full-sized man. Everyone lives happily ever after. Another important puzzle piece is “Two Companion Booklets” in Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology by Helen Craig McCullough (1990). In this otogi-zoshi, Issun-Boshi is born in Naniwa village in Settsu Province. (This story is full of specific details like that.) His parents are ashamed of his size (something Kelley said was un-Japanese). There are frequent poetry sections. Here, again, while seeking work, he hides under a man's clogs. When he’s sixteen and the princess is thirteen, he woos her. The wooing consists, again, of pretending she ate his rice. He leaves following his new wife as she heads towards Naniwa. Then they’re overtaken by two oni. Issun fights them off and gets a magic mallet that makes him full-size. The newlyweds go off together happy. Later, the Emperor hears the story, learns Issun is of noble heritage, and honors him greatly. These retellings indicate an older version of Issun-Boshi that was eventually toned down for children. Modern stories tend to be simpler. The trick that wins him a wife is disturbing and a little suggestive, with his accosting her in her sleep and ruining her reputation and honor - so that's gone. His parents are more affectionate, which is both softer for children and more in line with Japanese values (see Kelley). The scene where he hides under clogs is a nice illustration of his size. Buddha's crystal and other fairy stories (1908) preserves a lot of these details, including the Emperor's interest in Issun Boshi, but does not include the rice bit. There is a wealth of analysis on this Japanese site, and it's helpful even through Google Translate. The writer suggests that Issun was originally killed with the magic hammer, similar to traumatic transformations like the Frog Prince or Mamesuke. There are some interesting links between Issun Boshi and Ko-otoko no soshi. At the end, the Little Man becomes the god of Gojo shrine and his wife becomes the goddess Kannon (Tales of Tears and Laughter: Short Fiction of Medieval Japan). One of the gods of Gojo shrine is Sukuna-biko, an incredibly tiny god. As for Kannon: in most versions of Issun Boshi, she's the deity his parents ask for a son, and in some variants the princess is on her way to visit Kannon's shrine when Issun Boshi saves her. Issun Boshi is interesting because it’s such a unique variant of the Thumbling story, clearly native to Japan. Many others are simply the same story given different window dressing. Here, though, Issun Boshi’s narrative is fundamentally different. And Issun-Boshi shows up multiple times under different names (like Mamesuke), which I think is enough to establish it as its own variation.

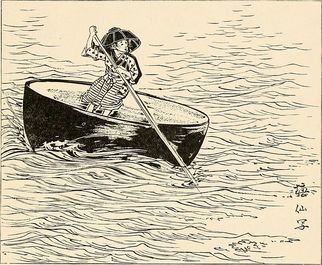

The typical thumbling is a trickster and child-archetype with simple, even repetitive adventures and a circular narrative. Thumbling’s Travels is one example – although by age he’s a young adult and ready to go out into the world and make a living, by the end he’s back at home with his parents, still technically a child. Issun Boshi’s story, however, is of a boy growing into a man. The common elements are very interesting. The wish for a child: yes Emphasis on small size, creative use of objects (like a needle for a sword): yes Helping on the farm: no Tricking people: no Being swallowed: Yes, but in a typical thumbling story, it’s just one of those wacky things that happens when you’re an inch tall. The thumbling is a passive agent and must be rescued. In Issun-Boshi, it’s a battle to defend his princess. Finally, instead of remaining small all his life, Issun Boshi grows to full size, symbolically becoming an adult. Issun Boshi may have been recorded even before Tom Thumb. It’s one of the otogi-zoshi – a later term for popular stories written mostly in the Muromachi period from 1392 to 1573. It may have not become widespread until the early Edo period. Frustratingly, that’s a pretty big window of time, and I haven’t been able to find anything to narrow that down. Most early manuscripts have no dates and the identities of their authors are also a mystery. The copies that do have dates are usually retellings or copies from the Edo period. Haruo Shirane mentions that the oldest versions of Issun Boshi “[survive] in a mere three manuscripts” but doesn’t say which they are, and his source for this is presumably in Japanese, rendering it inaccessible to me for now. Issun Bôshi means “One Sun Boy” – a “sun” being equal to just over an inch. Thus, in English, he is sometimes renamed some variation on Little One-Inch. Unlike European tales, which tend to place stories in vague locations, it is very specific. Issun Boshi is born after his parents pray at Sumiyoshi sanjin, an ancient Shinto shrine in Osaka. He travels across Osaka Bay in a rice bowl and has an adventure in Kyoto. The Yanagita Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale lists multiple variants of this story under different names, such as Issunbo or Issun Kotaro. More distantly related, Virginia Skord mentions eleven otogi-zoshi tales about a dwarf hero winning a wife and climbing in social status. Issun Boshi is one category. The other two categories are Ko Otoko (Little Man) and Hikyūdono (Lord Dwarf). Ko Otoko, with its one-foot-tall hero Toshihisa, has a near-identical plotline to Lazy Taro. He eventually becomes the god of Gojo Shrine and his wife becomes Kannon, a goddess of childrearing who is Buddhist in origin. (Incidentally, Issun-Boshi’s princess is attacked while on her way to pray at Kannon’s shrine.) The story of Hikyūdono is a cross between Issun Boshi and Ko Otoko, but I haven’t been able to find more information on it yet. This story is probably one of the more well-known thumbling tales, and I think that from a storytelling standpoint, it may be better than the typical Thumbling. Sources

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed