|

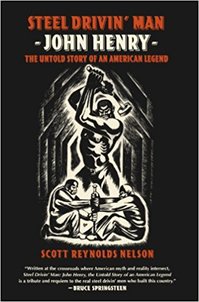

Steel Drivin' Man: John Henry - The Untold Story of an American Legend, by Scott Reynolds Nelson, recounts an effort to research the story behind the traditional song.

I came across this when I found the children's edition, Ain't Nothing But a Man: My Quest to Find the Real John Henry, at my library. It was told in an immediate first-person narrative, and I found it a great work for younger readers. It teaches kids how to do historical research and investigate folklore. After looking through it, I knew I had to read the full edition. I thoroughly enjoyed both versions, although I leaned more towards the one for adult readers, which was longer and more in-depth. It's filled with resources, looks at different versions of the John Henry song and its evolution, and visits to the area where the song would have originated. Nelson ultimately comes up with a theory for the origin of the song, and a candidate for a historical John Henry. Not everyone will agree with the theory, but I found Nelson's process fascinating and the theory fairly convincing. More than anything, the moment where the pieces fall into place is fantastic. A lot of effort went into this book and it shows. I recommend both versions to anyone interested in researching folklore.

0 Comments

What plant was Rapunzel named for? In the original German, the food that her mother desires is "rapunzel," plural "rapunzeln," but the proper English translation remains mysterious. One writer gave up with the pronouncement that "hardly anybody has the least idea what rampion is or looks like, though it is clearly some kind of salad vegetable" (Blamires, Telling Tales, 161).

This is not entirely true. The problem is that we have several ideas. Multiple plants are known, in German, as rapunzel. I have come across four that are frequently attributed as the plant of the fairytale.

The only clue we really have from the story is that the pregnant woman eats it in a salad, and that perhaps her craving seems a little strange. Any of these plants would fit that description. In fact, the name Rapunzel is actually a unique addition by Schulz. In the older and more widespread tales from France and Italy, as we've looked at over the past few weeks, the plant is parsley. This is reflected in the names of various heroines: Petrosinella, Persinette, Prezzemolina, Parsillette, and others. In the Italian "Petrosinella," the oldest known Rapunzel tale, there is no explanation needed for the parsley. It is used to flavor the tale with innuendo. In "Persinette" (1698), Charlotte-Rose de Caumont La Force explains that "In those days, parsley was extremely rare in these lands; the Fairy had imported some from India, and it could be found nowhere else in the country but in her garden." Parsley is native to the central and eastern Mediterranean, but would still have been familiar to La Force's audience. The herb had been in France for a long time. Charlemagne and Catherine de Medici, for instance, had it in their royal gardens. La Force's fanciful explanation of the rare parsley places the story in a distant land and/or time. There's also a wry little comment about the wife's unusual hunger: "Parsley must have tasted excellent in those days." Schulz approached the tale nearly a hundred years later in his collection of tales, Kleine Romane. His translation of "Persinette" contains various small changes, but the most significant was that he changed the plant, and with it, the girl's name. In his translation, the fairy's garden includes "Rapunzeln, which were very rare at the time. The fairy had brought it from over the sea, and there was none in the country except in her garden." There is still the comment "back then the Rapunzeln tasted wonderful." Schulz's "Rapunzel" was the version which influenced the Brothers Grimm (who were apparently unaware of the French fairytale). Their first version of Rapunzel is very terse and simple, in line with oral storytelling, so it's likely that they were relying on an informant who had read Schulz. If not for Schulz's creativity, we might today have an alternate fairytale chant of "Petersilchen, Petersilchen, let down your hair!" So this whole question of plants must begin from a different place - because it wasn't Rapunzel to begin with. The meaning of parsley In the older stories, parsley was rich with symbolism, associated with desire and fertility. The Greek physician Dioscorides wrote that parsley "provokes venery and bodily lust." The story of "Petrosinella" relied on this; there is a salacious line about the prince visiting the girl to enjoy the "parsley sauce of love." English children were told that babies were found in parsley beds (Folkard, Waring). According to Waring's Dictionary of Omens and Superstitions (p. 174), "Some country women still repeat an old saying that to sow parsley will sow babies." In another superstition, too much parsley in your garden would mean that "female influences reigned" and only baby girls would be born! (Baker, 1977) Occasionally it could be dangerous. In Greece, parsley was a funerary herb and had associations with death. Richard Folkard mentioned an English superstition that transplanting parsley would offend "the guardian spirit who watches over the Parsley-beds," leading to ill fortune. (Hmmm... very fitting for the Rapunzel story.) Parsley featured in many folk remedies. It was used on swollen breasts and in cures for urinary ailments. According to Thompson, "A craving for parsley of the mother would make immediate sense" due to its use in traditional medicine (pp. 32-33). It was also used by midwives to speed up labor when a mother was struggling with a long childbirth, and in the early stages of pregnancy, it could be used as an abortifacient. Much has been made of the abortion possibility in connection with Rapunzel. This particularly colors Basile's version, where Petrosinella's father is never mentioned, and her mother acts alone in stealing parsley from the ogress's garden. However, in "Persinette," La Force gives us a married couple who do want children but still ultimately give up their daughter in exchange for the precious parsley. Why? Well, abortion is not parsley's only connection; look at all the other beliefs surrounding parsley and fertility. It could also indicate that the mother was sickly or facing a difficult childbirth. Also, don't forget just how much importance was placed on pregnancy cravings. Pascadozzia, for instance, claims to fear that her child will have a disfiguring birthmark if she doesn't obey her cravings. See Holly Tucker's Pregnant Fictions for more on just how drastic these ideas could get, and how much sway pregnant women held. Persinette's parents may have seen no other option, with the lives of both mother and child potentially on the line. If not parsley, another symbolic plant typically features in Rapunzel-type tales: herbs such as fennel, or fruit such as apples. There are levels of erotic symbolism. A pregnant woman lusts uncontrollably after a food associated with desire. Her child is named for that food and grows up locked away to keep her from male advances. Even so, her guardians are never able to prevent her from eventually becoming sexually active when she reaches maturity. Her name and her nature are linked. Why the Change? Swapping rapunzel for parsley boots all of those superstitions, folk remedies, and symbols. Why exactly did Schulz change it? Here are some theories I've come across: Theory 1: Rapunzel would have made more sense than parsley to a German audience. Kate Forsyth's excellent case study The Rebirth of Rapunzel suggested that "Schulz may have changed the heroine’s name because parsley is a Mediterranean plant that grows best in warm, temperate climates, and so may have been relatively unknown in northern Germany, where Schulz was born." In the exact opposite direction, writer Gabriele Uhlmann concluded that the plant was lamb's lettuce, based on the statement that rapunzeln was rare, and the fact that lamb's lettuce was imported to Germany. Note that the line about the plant being rare is a direct translation of La Force's joke. Either way, both of these theories rely on the idea that rapunzel would have made more sense than parsley - either more familiar, or more rare and alluring, to a German audience. What do German books of the time indicate? Johann Jakob Walter's Kunst- und Lustgärtners in Stuttgart Practische Anleitung zur Garten-Kunst (1779) does feature parsley under the German names petersilie and peterling, with instructions for growing it in gardens. Walter also listed three rapunzels - Campanula rapunculus (rampion bellflower), Oenothera biennis (evening primrose), and finally Phyteuna spicata (spiked rampion) - while mentioning that there were still others out there. He differentiated them by calling them blue-flowered Rapunzel, yellow-flowered Rapunzel, and forest Rapunzel. He attributed Oenothera biennis as an American plant, but I got the impression that he was familiar with the other two plants growing wild in Germany. Joachim Heinrich Campe's 1809 book Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprach lists numerous plants as Rapunzel. Campanula rapunculus is first, but attributed to Switzerland, France and England. Next are Phyteuna spicata and Valerianella locusta (lamb's lettuce), both attributed to Germany. Finally is Oenothera biennis. He notes the first three as frequently eaten in salads. This doesn't help much. All I can say is that when Schulz was writing, parsley was known in Germany, and so were multiple plants known as rapunzel. Perhaps there's a clue in other fairytales. In 1812 - writing 22 years after Schulz - we have Johann Gustav Büsching's story "Das Mahrchen von der Padde," or "The Tale of the Toad," in Volkssagen, Märchen und Legenden. In this Rapunzel-like tale, the parsley-munching heroine is named Petersilie. So we have another German collector from roughly the same era, collecting a similar tale, who did not see any problems with keeping a character named Parsley. He didn't seem to worry that German readers would find parsley too faraway or too mundane. It was evidently a story native to Germany, parsley and all. (However, an English translator, Edgar Taylor, altered the name to "Cherry the Frog Bride" - presumably to make the name prettier.) Theory 2: Schulz was intentionally trying to erase the symbolism of parsley, particularly its use as an aphrodisiac and/or abortifacient. Personally, I doubt that Schulz was trying to erase erotic symbolism from the story. I also doubt that he was trying to erase female agency - yes, that's a theory I've run into. It's true that the Grimms made edits and removed things they didn't feel were appropriate. But they weren't the ones who changed the plant! Schulz's edits consisted mostly of adding his own little details to explain plot holes or color the story. He kept the story as La Force wrote it, including the pregnancy as well as the strict but ultimately loving fairy godmother who reunites with Rapunzel at the end. There is no erasure of eroticism going on here. There is no demonizing of the older, magical woman. The Grimms - who had exactly nothing to do with the Rapunzel name - were the ones who edited out the unwed pregnancy and transformed the benevolent fairy into a nasty old witch named Mother Gothel. Even then, while their edits made Rapunzel dangerously foolish, they also gave her an element of agency that neither La Force or Schulz gave her: the Grimm Rapunzel actively tries to run away from Gothel, weaving a ladder to escape her tower. Theory 3: Schulz thought Rapunzel was a cooler name than Petersilchen (the direct translation of Persinette). This is another theory brought up by Forsyth: perhaps Rapunzel was more appealing to Schulz's ear. Swiss scholar Max Lüthi wrote that "Rapunzel sounds better in the German tale than Persinette, it has a more forceful sound than Petersilchen... To be sure , in folk beliefs the plants called 'Rapunzel' do not play any important role, quite in contrast to those... such as parsley and fennel, apples and pears, which are attributed eroticizing and talismanic properties" (as quoted in McGlathery, Fairy Tale Romance, p. 130). Perhaps there's a clue in other translations. Schulz was not the only one to make edits to a literary tale which he was presenting to the audience of another country. When it came to exporting the Grimms' tales, English translators were faced with some problems. Most chose to keep Rapunzel's name. A valid choice, but one that leaves the name meaningless to English-speakers. Rapunzel just isn't familiar as a plant name to a lot of Americans. As Forsyth put it, "the change of the heroine’s name to Rapunzel drained much of the symbolic meaning from the herb, and in many cases led to the link between girl and plant being broken." In the most drastic departure, John Edward Taylor translated Rapunzel for The Fairy Ring: A Collection of Tales and Traditions in 1846 . . . as "Violet." Rather than craving salad, the mother demands her own bouquet of the sweet-smelling violets that only grow in the fairy's garden. Taylor stripped the fairytale of even more symbolism, made the heroine's name mundane and ordinary, and made her parents dangerously stupid and greedy (really . . . the wife demands a fresh bouquet every day, even though she can see and smell the violets from her window. And she's not even eating them). Martin Sutton, attributing Valeriana locusta as the original rapunzel, suggested that Taylor was avoiding not only the implications of pregnancy and cravings, but a possible link to the drug valerian, used for anxiety and sleep disorders. Fortunately, "Violet" did not catch on. An anonymously translated 1853 English version, Household Stories Collected by the Brothers Grimm, changed the plant to radishes but kept the Rapunzel name without explanation. H. B. Paull published Grimm's Fairy Tales in 1868, with the story under the title of "The Garden of the Sorceress." In a stroke of brilliance, she translated rapunzeln as lettuce and named her heroine Letitia, "Lettice" for short. Home Stories, in 1855, described the plant as "the most beautiful rampions." Mrs. Edgar Lucas used the translation corn-salad in Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (1900). Corn-salad, again, is an alternate name for Valerianella locusta or lamb's lettuce. In the 1909 edition, however, she changed the plant to rampion. Throughout all translations, rampion gradually took over in English as the most common translation. Otherwise, translators tended to leave it as "rapunzel." Conclusion The answer to the change lies with Schulz. So who was Schulz? What kind of translator was he? Was he a Taylor, a strict prude who wanted a pretty and innocent plant? Was he a Paull, with a hand for wordplay? I think Schulz was simply a storyteller. He stayed faithful to La Force's story, but he added small details, spicing it up rather than doing a flat translation. For instance, La Force simply says that Persinette had good food, but Schulz gives Rapunzel a detailed meal including marzipan. He also adds that Rapunzel doesn't just let her hair down, but winds it around a window hook before allowing people to climb it. When Rapunzel's prince goes missing, the king is left worrying about the succession of the kingdom. In essence, Schulz liked include practical little details that made the story more realistic and immediate. "Parsley" might have been all right for another collector, such as Büsching, but it didn't cut it for Schulz. I think all three theories for Rapunzel's name change are valid, and they could work together without conflicting. Schulz could very likely have preferred the sound of Rapunzel to Petersilchen. Maybe he did think it would make more sense than parsley to his German audience. And with his practical side, maybe he knew parsley could pose a danger to pregnancy; he may have thought that didn't suit La Force's story, in which a happily married woman eagerly awaits her firstborn child. This still leaves the question of which rapunzel he meant. There were at least four he might have heard of. We know that La Force's parsley and Schulz's rapunzel are eaten in salads, and that they would not be considered all that delicious (see the joking remark that parsley must have tasted wonderful back then). Both parsley and multiple plants known as rapunzel could be found in German gardens of the time. I've never had the opportunity to do a taste test of these plants; the only one I've ever had is parsley as a garnish. I did start looking at images of the plants. Campanula rapunculus (rampion bellflower) and Oenothera biennis (evening primrose) are flowers. Phyteuma spicata (spiked rampion) has tall stalks topped with bristling spearheads. By process of elimination, Valerianella locusta - lamb's lettuce - looks the most similar to parsley. Not very similar - their leaves look very different - but both are leafy green vegetables. And both of them blossom with bunches of teeny-tiny whitish flowers. When I looked at pictures of them flowering, I instantly thought "That has to be it." Another note: we don't know what Schulz was thinking, but we may have an idea what the Grimms were thinking. The mother in the Grimms' "Rapunzel" is struck by the sight of the "fresh and green" vegetable when she sees it from a distance. The narrative is not entirely clear, but it does indicate that she wants the leaves in her salad and they are the main focus of her desire. Two things here: 1) Rampion bellflower and spiked rampion have edible leaves, but are primarily grown as root vegetables. 2) Rampion bellflower (again) and evening primrose would have been most recognizable by their blue or yellow blossoms, not by green leaves. Again... that leaves lamb's lettuce. In addition, the Grimms originated a dictionary series, "Deutsches Wörterbuch." In an 1893 edition, published after their deaths, rapunzel is defined first as "die salatpflanze valeriana locusta, feld-lattich." Lamb's lettuce. The others come in second. Evening primrose doesn't even make it into the entry - it gets listed on its own as "rapunzelsellerie." So why did rampion take over as the English translation of rapunzel? Out of the English options, rampion has the most visual similarity to "rapunzel." It also has perhaps a slightly more romantic look to it. You can't name a fairytale princess "Corn Salad." Or you could, but it would be a brave choice. Quite a few translators struggled with the name, as seen in "Violet." In addition, English and American translators may simply not have been familiar with German garden vegetables. The other plants all have their points or bring intriguing connections to the story. However, I believe the rapunzel plant is most likely Valerianella locusta - lamb's lettuce or corn salad. Personally, I'd love to read a study of the tale from a German botanist. Further Reading

And more |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed