|

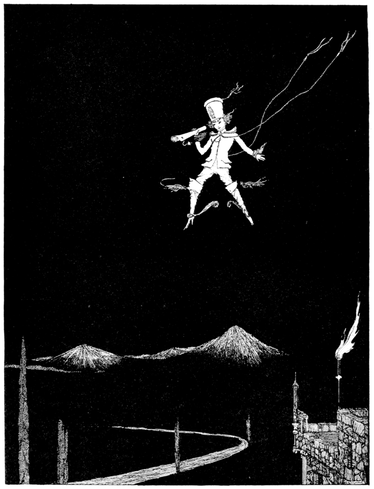

Charles Perrault's fairytale "Le Petit Poucet" - literally "The Little Thumb," my preferred name for it being "Hop o' my Thumb" - has a lot to unpack. In one of the most memorable scenes, Hop o' my Thumb flees with his brothers while the ogre pursues them in seven-league boots. However, the ogre tires and falls asleep, and Hop steals the boots for himself. He goes on to use them as a royal messenger.

Seven-league boots (or as Perrault called them, "bottes de sept lieues," will allow the wearer to walk seven leagues in one step. A league was roughly the distance that a person could walk in one hour, so about three miles. Seven-league boots would thus carry you twenty-one miles at every stride. Seven is a number rich in symbolism and particularly recurrent in "Hop o' my Thumb." Hop is one of seven brothers. The ogre has seven daughters. This was not the first appearance of seven-league boots in Perrault's fairytales. In his version of Sleeping Beauty, there is a brief appearance by "a little dwarf who had a pair of seven-league boots, which are boots that enable one to cover seven leagues at a single step." This is where we actually learn what the boots do - "Le Petit Poucet" leaves the definition out. The dwarf in Sleeping Beauty even serves as a messenger, exactly the same vocation as Hop o' my Thumb. He is a bit character and most adaptations do not include him. Is this a cameo by Hop? Do Perrault's tales share a universe? And what drew Perrault more than once to this specific image, of the incredibly small man in the magic boots? The idea of magical footwear that enables people to travel incredible distances is a universal one, but it seems Perrault made up this particular variation. It spread quickly. In Finnish, they are "seitsemän peninkulman saappaat." In Russian, сапоги-скороходы (sapogi-skorokhody, or fast-walker boots). In German, they are siebenmeilenstiefel. In the Hungarian tale of "Zsuzska and the Devil" - basically a genderflip of Hop o' my Thumb - the heroine steals tengerlépő cipődet, or sea-striding shoes. "The Bee and the Orange Tree" by Madame d'Aulnoy and "Okerlo" by the Grimms feature seven-league boots and a chase scene. The Grimms' "Sweetheart Roland" includes meilenstiefel, literally "mile-boots." An African-American version of the story is "John and the Devil's Daughter," by Virginia Hamilton in The People Could Fly. The idea goes far back in history and mythology. In Greek mythology, of course, there are the Talaria, the winged sandals which allow the god Hermes to fly. In Chinese myth, there are the Ǒusībùyúnlǚ (Cloud-stepping Shoes), which allow the wearer to walk on the clouds. In the Irish tale of King Fergus, the luchorpain gives Fergus shoes that let him safely walk underwater or on water. In Teutonic Mythology, Jacob Grimm mentioned "gefeite schuhe" or "fairy shoes," "with which one could travel faster on the ground, and perhaps through the air." He directly compares these to Hermes' winged sandals and to the seven-league boots. In some versions, the magical traveling shoes are part of a set. In the 1621 version of Tom Thumb, Tom receives multiple gifts from his fairy godmother: a cap that bestows knowledge, a ring of invisibility, a girdle that enables shapeshifting, and finally “a payre of shooes, (that being on his feete) would in a moment carry him to any part of the earth, and to be any time where hee pleased.” In a brief scene, Tom dons the shoes and is "carried as quicke as thought" across the world to view anthropophages, cyclopes, and other monsters. "Jack the Giant-Killer" (1711) borrowed these elements, with Jack winning from a giant a coat of invisibility, a cap of knowledge, a fine sword, and "shoes of swiftness." This is similar to "The King of the Golden Mountain" (Grimm), where the hero tricks three giants into giving him a magic sword, a cloak of invisibility, and "a pair of boots which could transport the wearer to any place he wished in a moment." A similar tale is the Norwegian "Soria Moria Castle" (Asbjørnsen and Moe) with boots that make strides of twenty miles. In "The Iron Shoes," a Bavarian tale collected by Franz Xaver von Schonwerth, the hero's boots let him travel a hundred miles per step and run alongside the wind. There are a multitude of other examples. These objects are all common in legend and might originate in Greek mythology: the sandals of Hermes, the helm of Hades which grants invisibility, and the many transformations of Proteus. A mantle of invisibility belonging to King Arthur is mentioned in Culhwch and Olwen (c. 1100) and other Welsh myths. The tarnkappe - a similar object - plays a role in the Middle High German epic of the Nibelungenlied (c. 1200). Shapeshifting with or without the help of a magic object is a widespread trope throughout world mythology. The hero typically receives these magical tools from a supernatural force: he receives them from the gods or a fairy, or steals them from a monster. The ancestor of them all is the Greek hero Perseus. He is entrusted by the gods with the helm of invisibility and winged sandals, which he uses to slay Medusa the Gorgo. Hop o’ my Thumb bears absolutely no resemblance to the popular modern version of Tom Thumb - which is why it drives me nuts when people mix up the titles! However, there are a few similarities to the 1621 prose Tom Thumb.

Could Perrault have been inspired by Tom Thumb? Is that why he included an unusually small character wearing magic running shoes in two separate stories? Or did he take inspiration from the many other tales of magical shoes? In this case, I think it's very possible he was inspired by the 1621 Tom Thumb. The beginning of Hop o' my Thumb always struck me as a bit out of place; his nickname and implied supernatural state of birth are irrelevant to the story. It's almost as if they were imported from another tale . . . a tale closer to Tom Thumb. On a final note that interested me: unlike Perseus, Hop o’ my Thumb, and Jack the Giant-Killer, Tom Thumb does not use his magical tools to fight any monsters (although he has two run-ins with murderous giants). However, when traveling with his magic shoes, he does see monsters: "men without heads, their faces on their breasts, some with one legge, some with one eye in the forehead, some of one shape, some of another." Their presence serves to indicate just how far he has traveled. Monopods or sciapods are legendary people with only one leg. Blemmyae or akephaloi are headless men with their faces on their chests. Cyclopes or Arimaspi are beings with only one eye. They appeared in the work of Greek writers like Herodotus and Pliny the Elder. Their legends showed up in bestiaries and maps throughout the Middle Ages. Pliny the Elder placed cyclopes in Italy, blemmyae in North Africa, and monopods in India. Some bestiaries put the one-eyed "Arimaspians" in Scythia, in eastern Europe. So magical boots of travel are a very widespread and old idea, usually used in combination with other magical tools, but occasionally appearing on their own. They may have been Perrault's own creative touch. In tales similar to Hop o' my Thumb, there is frequently a chase where the hero must escape the villain, and does so by various means. Hansel and Gretel ride away on a duck. Other characters, like those in Sweetheart Roland, disguise themselves in a transformation chase. Perrault gave his hero magic boots for this scene, and codified them not just as magic boots but as seven-league boots (repeating the use of the number seven). Their presence, along with Petit Poucet's name, is fascinatingly reminiscent of the 1621 English Tom Thumb. What makes it even more interesting to me is that Perrault also used that Tom Thumb-esque character in Perrault's Sleeping Beauty.

0 Comments

One classic fairytale is "Le Petit Poucet" by Charles Perrault - often translated in English as Hop o' My Thumb. A poor woodcutter and his wife, starving in poverty, decide to lighten their burden by abandoning their seven children in the woods. The youngest child, Hop o' my Thumb, attempts to mark the way home with a trail of breadcrumbs, but it's eaten by birds. The lost boys make their way to an ogre's house where they sleep for the night. The ogre prepares to kill them in their sleep; however, an alert Hop o' my Thumb switches the boys' nightcaps for the golden crowns worn by the ogre's seven daughters. While the ogre mistakenly slaughters his own children in the dark, the boys escape. Hop also manages to steal the ogre's seven league boots and treasure, ensuring his family will never starve again.

This tale is Aarne Thompson type 327B, "The Dwarf and the Giant" or "The Small Boy Defeats the Ogre." However, this title ignores the fact that there are stories where a girl fights the ogre, and that these stories are just as widespread and enduring. One ogre-fighting girl is the Scottish "Molly Whuppie." Three abandoned girls wind up at the home of a giant and his wife, who take them in for the night. The giant, plotting to eat the lost girls, places straw ropes around their necks and gold chains around the necks of his own daughters. Molly swaps the necklaces and, while the giant kills his own children, she and her sisters escape. Then, to win princely husbands for her sisters and herself, Molly sneaks back into the giant's house three times. Each time she steals marvelous treasures (much like Jack and the Beanstalk). At one point the giant captures her in a sack, but she tricks his wife into taking her place. She makes her final escape by running across a bridge of one hair, where the giant can't follow her. This tale was published by Joseph Jacobs; his source was the Aberdeenshire tale "Mally Whuppy." He rendered the story in standard English text and changed Mally to Molly. In Scottish, Whuppie or Whippy could be a contemptuous name for a disrespectful girl, but it was also an adjective for active, agile, or clever. This story probably originated with a near-identical tale from the isle of Islay: Maol a Chliobain or Maol a Mhoibean. J. F. Campbell, the collector, says that the spelling is phonetic but doesn't provide many clues to the meaning. Maol means, literally, bare or bald. Hannah Aitken pointed out that it could mean a devotee, a follower or servant who would have shaved their head in a tonsure. This word begins many Irish surnames, like Malcolm, meaning "devotee of St. Columba." When the story reached Aberdeenshire, the unfamiliar "Maol" became Mally or Molly, a nickname for Mary. According to Norman Macleod's Dictionary of the Gaelic Language, "moibean" is a mop. "Clib" is any dangling thing or the act of stumbling - leading to "clibein" or "cliobain," a hanging fold of loose skin, and "cliobaire," a clumsy person or a simpleton. Perhaps Maol a Chliobain means something like "Servant Simpleton" - a likely name for a despised youngest child in a fairytale. Maol a Mhoibean could mean something like "Servant Mop." There are a wealth of similar heroines. The Scottish Kitty Ill-Pretts is named for her cleverness, ill pretts being "nasty tricks." The Irish Hairy Rouchy and Hairy Rucky have rough appearances, and Máirín Rua is named for her red hair and beard (!). Another Irish tale with similar elements is Smallhead and the King's Sons, although this is more a confusion of different tales. The bridge of one hair which Molly/Mally crosses is a striking image. This perhaps emphasizes the heroine's smallness and lightness, in contrast to the giant's size. In "Maol a Chliobain," the hair comes from her own head. In "Smallhead and the King's Sons," it's the "Bridge of Blood," over which murderers cannot walk. Based on examples like these, Joseph Jacobs theorized that this tale was Celtic in origin. However, female variants of 327B span far beyond Celtic countries. Finette Cendron is a French literary tale by Madame d'Aulnoy, published in 1697, which blends into Cinderella. The heroine has multiple names - Fine-Oreille (Sharp-Ear), Finette (Cunning) and Cendron (Cinders). Zsuzska and the Devil is a Hungarian version. Zsuzska (whose name translates basically to "Susie") steals ocean-striding shoes from the devil, echoing Hop o' My Thumb's seven-league boots. According to Linda Dégh, female-led versions of AT 327B are quite popular in Hungary. Fatma the Beautiful is a fairly long tale from Sudan. In the central section, Fatma the Beautiful and her six companions are captured by an ogress. Fatma stays awake all night, preventing the ogress from eating them, and the group is able to escape and feed the ogress to a crocodile. In the ending section, the girls find husbands; Fatma wears the skin of an old man, only removing it to bathe, and her would-be husband must uncover her true identity. (This last motif seems to be common in tales from the African continent.) Christine Goldberg counted twelve versions of this tale in Africa and the Middle East. The Algerian tale of "Histoire de Moche et des sept petites filles," or The Story of Moche and the Seven Little Girls, features a youngest-daughter-hero named Aïcha. She combines traits of Hop o' my Thumb and Cinderella, and defends her older sisters from a monstrous cat. This is only one of many African and Middle Eastern tales of a girl named Aicha who fights monsters. And the tale has made its way to the Americas. Mutsmag and Muncimeg, in the Appalachians, are identical to Molly Whuppie. Meg is a typical girl's name, and I've seen theories that the "muts" in Mutsmag means "dirty" (making the name a similar construction to Cinderella). It could also be "muns," small, or from the Scottish "munsie," an "odd-looking or ridiculously-dressed person" (see McCarthy). German "mut" is bravery. (See a rundown of name theories here.) In the 1930s, "Belle Finette" was recorded in Missouri. Peg Bearskin is a variant from Newfoundland. In Old-Fashioned Fairy Tales (1882) by Juliana Horatia Ewing, we have "The Little Darner," where a young girl uses her darning skills to charm and manipulate an ogre. One of the largest differences between the male and female variants of 327B is the naming pattern. Male heroes of 327B are likely to be stunted in growth - a dwarf, a half-man, or a precocious newborn infant. Le Petit Poucet is "when born no bigger than one's thumb" - earning him his name. In English, he has been called Thumbling, Little Tom Thumb, or Hop o' My Thumb. The last name is my favorite, since it helps to distinguish him. Note that despite the confusion of names, he is not really a thumbling character. His size is only remarked upon at his birth. He is thumb-sized at birth, but in the story proper, he is apparently an unusually small but still perfectly normal child. Look at other similar heroes' names:

The names of girls who fight ogres focus on the heroine's intelligence or beauty (or lack of beauty). The heroine is often a youngest child, but I have never encountered a version where she's tiny, as Hop o' My Thumb is. The girl's appearance can play a role in the tale, but if so, the focus is usually on her being dirty, wild or hairy. Where the hero of 327B is shrunken and shrimpy, the heroine has a masculine appearance. Máirín Rua has a beard; Fatma the Beautiful disguises herself as an old man. Outside Type 327B, there are still other female characters who face trials similar to Hop o' my Thumb and Molly Whuppie. Aarne-Thompson 327A, "The Children and the Witch," includes "Hansel and Gretel" (German) and "Nennello and Nennella" (Italian). Nennello and Nennella mean something like "little dwarf boy and little dwarf girl." Nennella, with her name and her adventure being swallowed by a large fish, is the closest to a Thumbling character. Bâpkhâdi, in a tale from India, is born from a blister on her father's thumb - a birth similar to many thumbling stories. In the opening to the tale, her parents abandon her and her six older sisters in the woods. However, after this episode, the tale turns into Cinderella. In Aarne-Thompson type 711, the beautiful and the ugly twin, an ugly sister protects a more beautiful sister, fights otherworldly forces, and wins a husband. This encompasses the Norwegian "Tatterhood," Scottish "Katie Crackernuts," and French Canadian "La Poiluse." It overlaps with previously mentioned tales like Mairin Rua and Peg Bearskin. One central motif to 327B is the trick where the hero swaps clothes, beds, or another identifying object, so that the villain kills their own offspring by mistake. This motif appears in in many other tales, even ones with completely different plots. A girl plays this trick in a Lyela tale from Africa mentioned by Christine Goldberg. In fact, one of the oldest appearances of this motif appears in Greek myth. There, two women - Ino and Themisto - play the roles of trickster heroine and villain. Madame D’Aulnoy’s “The Bee and the Orange Tree” and the Grimms’ "Sweetheart Roland" and "Okerlo" are very similar to 327B. However, they are their own tale type, ATU 313 or “The Magic Flight.” In these tales, a young woman is always the one fighting off the witch or ogre. She’s the one who switches hats, steals magic tools, and rescues others. The main difference is that while the heroes of ATU 327 are lost children, the heroes of ATU 313 are young lovers. But back to the the basic 327B tale. Both "The Dwarf and the Giant" and "Small Boy Defeats the Ogre" are flawed names, given that stories where a girl defeats the ogre are so widespread. These ogre-slaying girls pop up in Ireland, Scotland, Hungary, France, Egypt, and Persia, and have thrived in the Americas. I fully expect to find more out there. Sources

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed