|

Fairy tales are obsessed with hunger. There’s Thumbling, Jonah, Red Riding Hood, and Zeus's siblings, all gulped up only to emerge unharmed one way or another. In many stories, In stories from all over the world, parents threaten their children that some boogeyman will gobble them up if they don't behave.

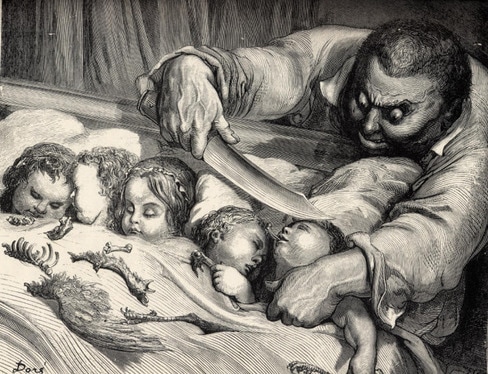

In Hop o' my Thumb, the ogre hungers for the flesh of children. In Jack and the Beanstalk, the giant chants "I smell the blood of an Englishman . . . I'll grind his bones to break my bread." These man-eating giants hearken back to monsters such as Polyphemus in the Odyssey. Hansel and Gretel's witch is the same character. The evil queen desires to eat Snow White's heart. In Perrault's Sleeping Beauty, the second half features the heroine's mother-in-law attempting to eat her and her children cooked with sauce piquante. And on the other hand there are stories where people are tricked into eating human flesh, especially the flesh of their loved ones - as in The Juniper Tree and some older versions of Red Riding Hood. In the Vietnamese story of Tấm and Cám and the Greek myth of Philomela, it's the hero tricking the villain into cannibalism. There's one theory that the frequently-digested Thumbling is a story related to how children process the concept of pregnancy and childbirth. This motif of being eaten and escaping appears in other tales, like Red Riding Hood and The Seven Kids. Earlier theories suggested Red Riding Hood was a myth-like tale of rebirth, with the girl as the sun and the wolf as the night. That school of thought has now been largely discarded, and it's more popular to read it in sexual terms, perhaps as the devourer eating a lover in order to possess her completely. Hunger in fairytales is often a stand-in for sexual desires. There are other factors behind the stories, though. I think it's partly ancestral fear, the fear of a bigger predator snatching you from your cave. It could also be a way to face the taboo. In the 1997 article “Incest in Indo-European Folktales,” D.L. Ashliman points out that “many fairy tales owe their longevity to an ability to address tabooed subjects in a symbolic manner." So, along with stories containing abuse or incest, there are stories like The Juniper Tree where people, even parental figures, turn to cannibalism. Perhaps this is also where the heroes taking harsh revenge come from. In a story, you can dance the villain to death in red-hot iron shoes or send her hurtling down the street in a barrel lined with nails. There are some beliefs that eating your enemy - usually in a ritualized ceremony - will give you his strength, courage or life force. The Iroquois and Aztecs would do this with prisoners of war. The Sawi (Sawuy) people of New Guinea would give the victim's name, and thus his life force, to one of the villagers. In Tanzania and other areas of Africa, some superstitions hold that albinos are magical and their bodyparts can be used in talismans or potions. In Europe, human fat, flesh, blood and bones were consumed in medicines until around 1750. Consuming the life force would be the goal of Snow White's evil queen, who seeks to eat her stepdaughter's heart and once again be the fairest in the land. Similarly, in Norse mythology, eating a dragon's heart gives Sigurd the power of prophecy. Civilization vs. Barbarism In The Irresistible Fairytale, Jack Zipes says, “Almost all cultures have cannibalistic ogres and giants or dragons and monsters that threaten a community. Almost all cultures have tales in which a protagonist goes on a quest to combat a ferocious savage. The quest or combat tale is undertaken in the name of civilization or humanity against the forces of voracity or uncontrolled appetite.” (page 8.) In The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World, Zipes says something along the same lines: "Though each one of the Tom Thumb tales differs, they all focus on the same major concerns of The Odyssey as discussed by Adorno and Horkheimer: self-preservation and self-advancement through the use of reason to avoid being swallowed up by the appetite of unruly natural forces." This describes the quests of Hop o' my Thumb, Jack, Gretel, and others. All three of these tales begin with families in extreme poverty, on the verge of starvation. They begin with the hungry parents doing the unthinkable and abandoning their children in order to keep more food for themselves. Hunger thwarts the heroes again when birds eat their breadcrumb trail. Finally, they face a force trying to devour them. The tale reaches its happy ending when the heroes succeed, and in many cases even turn the monster's tools against them. Further Reading

2 Comments

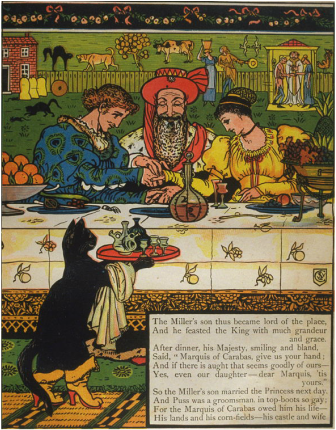

Perrault's "Puss in Boots" begins with a poor miller's son, alone in the world except for a pet cat. Things look bleak, until the cat speaks up. It has a plan to put the boy on a path straight up the social ladder, turning him from a beggar to the future king.

This is accomplished by a whole lot of lying. When the cat first introduces his master to the king and his daughter, he dubs him the Marquis of Carabas. The name is mentioned again and again throughout the story, and becomes the moniker by which the character is always referred. We never learn his real name. So what is Carabas? It's likely just a nonsense word created by Perrault. The cat makes up a title out of whole-cloth and gradually adds a princess and a castle to back it up. Carabas is not a real place. It's not supposed to be. In The Great Fairy Tale Tradition, Jack Zipes suggests that Perrault could have taken inspiration from stories of a fool in Alexandria named Carabas, who people mocked by treating like a king, or the Turkish word "Carabag" for a summer vacation spot in the mountains. A carabas is also a French term for a cage-like carriage, but the earliest mention I find of it is from 1874, well after Perrault, and it may derive from the Puss in Boots story. There are a few similar words in French. "Car" is a dialect word from Picardy meaning something along the lines of "that's why." "Caraba" is cashew nut oil. However, like the previous examples, these words have no obvious connection to Perrault's story. There are many versions of this tale, and some include similar aliases. A Swedish version has the Princess of Cattenburg, which is clearly Cat Town. Similarly, there's the Earl of Cattenborough in Joseph Jacobs' European Fairy Tales. It's unclear where exactly Jacobs got this story. The characters' names (Charles, Sam, and John) are all very English. He may have drawn elements from different variants of the Puss tale. He specifically mentions the Princess of Cattenburg, so he may have gotten the name here. Italian versions are Don Joseph Pear (derived from the pear tree that he owns) and Count Piro (which I believe also derives from pears in the story). Other Italian versions have the cat or fox helper rename its master Caglioso or Gagliuso, a name meaning youth. Actually, in quite a few of these versions, the animal helper is female. Perrault made the character male. Sometimes it's explained as a magical cat or an enchanted princess, but Perrault's cat just happens to be able to talk. SOURCES

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed