|

I found a mention of the word pillywiggin from before 1977!

. . . sort of. The spelling's right, but in this context it has nothing to do with fairies or flowers. In fact, it's possible evidence against pillywiggins as flower fairies. Firstly, some background. One of the things about the word pillywiggin is that it does sound like an English fairy name, very much so. There are fairy names that are very close. It almost feels criminal that pillywiggin doesn't show up among them in the pages of an English dialect dictionary somewhere. Pigwiggen. The word appears as early as 1594 in the Tragical Reign of Selimus: "Now will I be as stately to them as if I were master Pigwiggen our constable." Nash's Have with you to Saffron Walden (1596) uses the word "piggen-de-wiggen" as a term for a sweetheart. In 1627, Michael Drayton produced his epic-in-miniature "Nimphidia." Here, Queen Mab has an affair with the fairy knight Pigwiggen, and an angry King Oberon challenges him to a duel. From here, Pigwiggen or Pigwiggin came to mean any excessively tiny thing. The etymology is unknown. The first syllable, "pig," may be related to pug or puck, other types of fairies (a root which could also be related to phouka or pixie). Other suggestions would connect it to "earwig." Notably, around 1657, Josua Poole's English Parnassus, or, a Helpe to English Poesie gave a list of denizens of the fairy court. Nearly all of the names were from "Nimphidia." Except that instead of Pigwiggen, it gives Periwiggin - a word even closer to "pillywiggin." The next name in the list is "Periwinckle," so it may be an error of accidentally combining two similar names. (Periwinckle or Perriwinckle was Oberon's barber in the 1638 play Amyntas, or the Impossible Dowry.) Also possible is that the writer unconsciously brought in the word "periwig," meaning a wig. Pigwiggen later developed into the similar Pigwidgeon. Pigwidgeons appeared as gnomelike beings and miniature fairies in the fantasy writing of Frank Richard Stockton (1834-1902) and others. Skillywidden is the given name of one fairy in a story from Cornwall (Popular Romances of the West of England, 1865). In a reversal of the usual changeling tale, a farmer discovers a tiny fairy child in the heather and takes him home. The farmer's children play with him and name him Bobby Griglans (i.e., Bobby Heather). However, one day they see a fairy man and woman crying for their lost child, "Skillywidden." They release the fairy child, who runs to his mother and vanishes off into Fairyland. Intriguingly, there is a real-world Skillywadden Moor as well as a farm and a barn under the same name, all neighboring the location where the story is set. Note the different spelling. I'm not sure whether the moor took its name from the story or vice versa. The etymology is obscure. It could mean white wings, from Cornish askell (fin or wing) and gwydn (white). By comparison, the Cornish word for a bat is sgelli-grehan or skelli-grehan, literally "leather wings." Alternately, 1000 Cornish place names explained (1983) tentatively defines Skillywadden as "poor nooks." Compared to Pillywiggin, this name has same number of syllables and many of the same letters: _illywi__en. When I contacted English folklorist Jeremy Harte, he pointed out that Skillywidden and Pigwiggen combine perfectly into Pillywiggen. Someone could easily have mixed up the two words. The writer Enys Tregarthen frequently used the word “skillywidden” as a generic term for baby fairies. In Folk Tales from the West (1971), Eileen Molony retold the Skillywidden story and left the fairy nameless, but used "skillywiddons" for his species of hairy, mischievous sprites. Skillywiddens could definitely qualify as "popularized," the word used for pillywiggins in their first known appearance. Pilwis is the name of a German field spirit (okay, not English, but bear with me). The variant spellings are where it gets interesting: pilwitze (plural pilwitzen), pilewizze, pelewysen, and pilwihten. In Jacob Grimm's Teutonic Mythology, the word was compared variously to wood-sprites, "hairy shaggy elves," and witches. Pilwisses or bilwisses were part of a class of feldgeister, or field spirits, who haunted cornfields. They ranged from malevolent bogeymen to personifications of the harvest. Like other elves, bilwisses might tangle hair, cause nightmares, or live in trees. I've collected a number of other words. The Pellings were a Welsh family supposedly descended from a fairy named Penelope (Y Cymmrodor, 1881). A wiggan tree is an ash tree (also wicken-tree, wich-tree, wicky, witch-hazel or witch-tree). There are ties between ash trees, magic, and witches in folklore. Piggin was the name of several familiar spirits in 16th/17th-century witch trials. Ursula Kemp, for instance, claimed a black toad named Piggin. (The name means pail or ladle.) (Rosen, Witchcraft in England, 1558-1618.) Pillicock appears in songs and rhymes such as Shakespeare's King Lear ("Pillicock sat upon Pillicock hill"). It's generally glossed as a slang term for penis. So is pillie wanton. However, Robert Gordon Latham's Dictionary of the English Language makes a valiant effort at interpreting Pillicock as a fairy name connected to Puck and the Pilwiz. Outside the fairytale field, pigwiggan or Peggy Wiggan is a bad fall. A piggy-whidden, from Cornish, is a runt piglet. A piggin-riggin is a small boy or girl. Pillie-winkie is a child's game. (English Dialect Dictionary vol. 4). Pirlie-winkie or peerie-winkie is the little finger and peerie-weerie-winkie is something excessively small (Transactions of the Philological Society). Wigan is an English town, and at least at one point in time was home to a site known as Pilly Toft (The history of Wigan, 1882) So these are common word constructions. Bear this in mind for later. Now: the pre-1977 sort-of mention of the word pillywiggin. Louisiana's Crowley Signal, December 14, 1917, featured an article on page 8 titled "Speed Up Your Needles; Soldiers Need Warm Garments." "[T]hose who are pilly-wiggin along with their knitting, thinking most anytime will do; and "it isn't very cold yet;" and "after Christmas I'll try" . . ." Finally! But there are issues. Not only is the word hyphenated, but it's apparently a verb (to pilly-wig?). A word "pilliwig" does show up in a few historical newspapers and magazines. "The Fate of Mr. Pilliwig" was a short story by N. P. Darling that appeared in Ballou's Monthly Magazine in 1871. All the characters had made-up surnames, another being Slingbillie. Similarly, in an 1880 article in the Huntingdon Journal, "pilliwig" was used as a random childish nonsense word. The most puzzling occurrence: in Kansas in the 1890s, pilliwig or pilly-wig briefly became a synonym for liquor. September 12, 1895, Enterprise Eagle, Enterprise, Kansas "[I]t seemed that the "pilly-wig" that he was alleged to have been selling affects the memory..." February 26, 1896, The Solomon Sentinel, Solomon, Kansas At the "largest brewing house in the world" . . . "its Guides shewed us the plant and processes for making "pilliwig" and other decoctions which maketh fools of men." June 17, 1896, The Solomon Sentinel, Solomon, Kansas "We regret to learn that Bro. J. W. Murray of Dillon Republican is so badly under the weather that he is compelled to take his medicine at the hands of a "pilliwig doctor." He says: "On these hot days when thirst is gnawing at your vitals and your tissues are consumed as by a burning fever, a visit to the hop tea dispensary on Main Street will put you in running order again." October 29, 1897, The Solomon Tribune, Solomon, Kansas There was a hot time in the old town last Saturday night. Two fights occured by the influences of "pilliwig." So, to sum up, we have one 1910s instance of a verb pilly-wig/pilly-wigging. Going by context, I would interpret the meaning as "procrastinating"; perhaps doing a very small amount at a time, or spending time on nonsense. There is no evidence of a noun “pillywiggin” existing before the 1970s. However, we do have instances of “pilliwig” used as a nonsense word. It pops up every decade or so through the late 1800s and 1900s (more in America than in England, it seems). However, it has no context or continuity. It’s so devoid of meaning that it can be used for anything and everything, from a clown in a 1960's children's TV show, to booze. To me, that lack of meaning indicates that pillywiggins in pop culture just weren't a thing. Maybe pillywig is recurrent because there are so many similar words in English that this is a natural word construction. Different authors could easily have come up with the same word, or have read a previous use of the word and subconsciously remembered it. Some 20th-century children's author could easily have constructed the word "pillywiggin" for a fantasy creature. I haven't given up on that possibility. However, it would be equally easy for fairy names like Pigwiggen and Skillywiddens to be garbled, combined, or misspelled. We have evidence of that very thing happening with "Periwiggin." Also in this series:

2 Comments

There's a popular conception that fairytales all take place a very long time ago, in ancient times with princesses and castles and knights. That's partly true. But then why are there no "modern" fairytales?

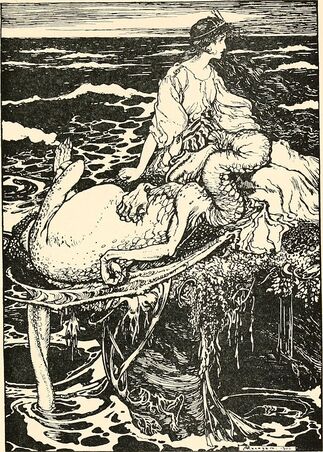

I believe most people who told oral folktales, while they may have featured princesses and castles and so on, pictured the events as happening in towns like their own, with technology like their own. Contemporary settings. Folktale collecting's major boom began around the early 1800s with the Brothers Grimm. We also had a wave of fairytale writers, like Hans Christian Andersen, inspired by folktales. The result of the folklore movement was fairytales frozen in time. Now that they were in print, they existed as the product of that time period. Just for context, the telegraph was invented in 1837. The first telephone was 1876, the light bulb 1878. You had Napoleon, the Louisiana Purchase, the American Civil War (in no particular order). People living in the 1800s would have lived to see the first films and World War II. The image at the top of this post is an illustration of the Grimms' tale "The Four Skillful Brothers." It looks very fantastical and medieval, right? That looks like the kind of dragon you'd slay with a sword. Spoiler alert: someone shoots that dragon with a gun. Guns actually appear a lot of fairytales, from the Grimms and otherwise. You see the same thing in literary fairytales like Hans Christian Andersen's. In Andersen, there's a wide range. The Marsh King's Daughter features Vikings, but The Steadfast Tin Soldier has tin soldiers, muskets, ballet, and plumbing. Today, there's a sort of "fairytale canon" in the popular mind, strongly influenced by Disney. Even Disney fairytales tend to be set in a vague, anachronistic past. For instance, Snow White is a mishmash of elements from different historical periods. Their clothing is medieval fantasy, but there's gas technology and a Bunsen burner in the Evil Queen's lair. The Bunsen burner was invented in the 1850s. Are there any modern fairytales set in modern times? It depends on what you mean. Although oral storytelling isn't as popular, we do have people continuing to retell and adapt fairytales as movies or as books. In many cases, these retellings are set in contemporary times. See Cinder Edna, a picture book by Ellen Jackson, where the main character takes a bus to the ball. There are also plenty of fantasy short stories which have modern flavors. Or even Internet folklore like Slenderman. But I do think that if you set out to collect oral folktales being told today, you will find fairytales set in worlds like those the storytellers inhabit. There are collections created well into the 20th century. Hasan el-Shamy has collected folktales from the Middle East. Another example is Barbara Rieti's Strange Terrain: The Fairy World in Newfoundland, published 1991. At one point in 1985, she attempted to track down the origins of a local tale of a little girl taken away by fairies. You would think of that as happening in a long-ago distant time - which Rieti initially did. But then she actually met the person involved, who was then in her sixties (and who did not seem happy at her experience being turned into a fairytale). She had been lost in the woods for over a week and suffered from hypothermia. This happened in the 1930s. I think there's a Disney-influenced imagining of fairytales as all taking place in the distant past, further influenced by a lack of context for just how recently these tales were set down in print. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed