|

In most traditional versions, Cinderella’s ball is a multi-night affair. She visits on three nights and dances with the prince three times. Often she wears more elaborate dresses each night, building more and more on the concept. She loses her shoe on the third night. Both Perrault’s Cendrillon and the Brothers Grimm’s Aschenputtel follow this model.

The rule of three also shows in versions where she has two stepsisters. Cinderella is one of three rivals. Her two stepsisters go to the ball first and try on the shoe first. Cinderella is the triumphant final contestant. The Rule of Three is a common storytelling or rhetorical technique across western literature including folktales. Even in modern times, think how many things come in threes, like the Three Musketeers. The number is also recurrent throughout the Bible (Jonah in the whale for three days) and in Christian teaching (like the Trinity). Three is the smallest possible number that’s still recognizable as a pattern. Patterns of three make the tale feel more satisfying, complete, or amusing, without the repetition becoming boring. In many modern retellings, however, Cinderella goes to one ball only. I think this began with stage adaptations such as pantomimes. Films followed suit, including the 1914 Cinderella film starring Mary Pickford, and the animated Disney film from 1950. In storytelling, it’s easy to skim quickly over the details of the ball. In stage or cinema, three spectacles of a kind might start to drag. These are visual adaptations and the fairytale’s exact repetition is not going to work. You could have three identical ball nights, or try to vary it up and make each occasion different (with all the set or animation costs involved) . . . or you could simply summarize it into one. Does this mean something has been lost? I don’t think so. The formats of the telling are different – a play, movie or a novel is very different from an oral folktale, and the same things won’t necessarily work across different mediums. Movies frequently condense their source material. Also, audiences’ tastes change. In the original, the three-night ball is really the main plot. Cinderella is a heroine completing a series of trials. Can she escape her family’s attention each night? Can she get another dress from her supernatural benefactor? Can she wow the prince each night and then slip away afterwards? In some versions she becomes a trickster, hiding behind a Clark Kent-esque disguise and savoring her own private joke. You can imagine Perrault’s Cinderella winking at the audience as she asks her sisters about the mysterious lady at the ball. The Grimm Cinderella gets up to some hijinks as she evades the lovelorn prince, scaling a tree or hiding in a pigeon coop. But modern retellings typically leave this out. In the fairytale, Cinderella and the prince develop a connection over three nights; initial attraction leads immediately to marriage. He can’t even recognize her through her rags and soot, being only able to identify her by her shoe. Not particularly romantic. Modern versions typically focus on the romance and on giving Cinderella a goal beyond just going to a party and finding a husband. The 1998 film Ever After, Marissa Meyer’s 2012 novel Cinder, and Disney’s 2015 live-action remake all spend the majority of the story building up Cinderella’s relationship with the prince, and her own personality and life goals. Instead of ball attendance being the main plot, the ball is a single dramatic scene. Cinderella gets one shot at wowing her prince, and so the ball is that much more significant. Gail Carson Levine’s Ella Enchanted (my favorite Cinderella retelling of all time) goes for three balls. However, Levine – like the other authors mentioned – builds a more unique plot and has Ella fall in love with her prince long before the festival. (I think the movie adaptation reduced the celebrations to a single coronation ball, though I have not watched it). The Grimm-inspired musical Into the Woods features three balls, but at least in the film adaptation, they take place mostly offscreen. The ball is not the focus. Instead, the focus is on Cinderella fleeing on three consecutive nights, and the slightly different events each time. Again, it’s avoiding too much repetition. Another thing: particularly if it’s a contemporary or high-school retelling, one-night events are often more common than multi-night recurring festivals. The 2004 movie A Cinderella Story made it a Halloween dance. Some of these stories still include the secret identity element by making it a masquerade ball, or having Cinderella not realize her beloved is the prince at first. Contemporary versions have an advantage in that the romantic interests can chat online to begin with, preserving their anonymity until it's time for the big finale. So it makes sense for the story to be updated. But the new emphasis on Cinderella having more personality, or more chemistry with the prince, is separate from the fact that many versions just have one ball. A lot of this may be the effect of film. Cinderella has been retold many times, and today a lot of people get their main exposure to fairytales through movie format. Disney is one of the main heavy-hitters, but even earlier versions (like the Mary Pickford film) had just one ball. You don’t see as many versions of Cinderella’s close cousin All-kinds-of-fur or Donkeyskin (which is probably rare because of the incest theme). I’ve seen three versions, and all featured the three balls. This story is a little different because it is an important plot point that the heroine has three different dresses, and of course she has to show them all off. However, I can’t think of any versions where the three dresses are condensed into one. If Disney had been daring enough to adapt this tale, we might have a standardized simplified version as we do with Cinderella. (While we’re on this subject, I would heartily recommend Jim Henson’s TV episode “Sapsorrow” – a combination of Cinderella and Donkeyskin including a dark spin on the glass slipper, where a king is unhappily bound by law to marry whoever his dead wife’s ring fits.) Other Blog Posts

1 Comment

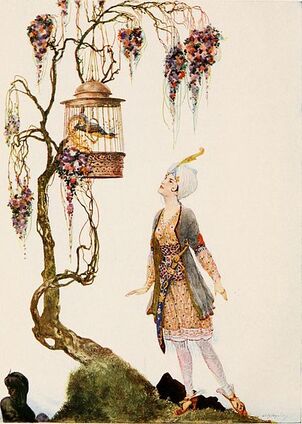

One of my favorite childhood fairytales was the expressively titled "The Two Sisters Who Envied Their Cadette" (or in more modern language, "The Two Sisters Who Envied Their Younger Sister.") This is one of the Arabian Nights, but it's actually part of a group of "orphan tales," which appeared in Antoine Galland's translation from the early 1700s, and not in the original manuscripts. Some, like Aladdin and Ali Baba, are actually more well-known than the original Nights, and I have to say Periezade was my absolute favorite when I read a collection as a kid.

The story begins with a king named Khusraw Shah or Khosrouschah. There were a few real Persian kings named Khosrau. This story’s Khosrau Shah comes off as capricious and murderous, but we'll get to that in a minute. He overhears three sisters talking. One dreams of marrying the king's baker, another of marrying the Sultan's chef, and the youngest and most beautiful says that she would marry the Sultan. While the first two make their wishes out of gluttony, the youngest is said by the narrator to have more sense. Amused, the Sultan has them fetched to the palace and performs all three weddings on the spot. Unfortunately, this sows resentment; the older sisters grow jealous and plot their sister's demise. Over the next few years, she gives birth to two sons and a daughter, and each time her sisters replace them with a puppy, a kitten, and a wooden stick that they pass off as a molar pregnancy. They secretly put the babies in a basket and boat them off down the canal. The king initially wants to execute his wife straight off, but his advisors talk him down and he decides to instead have her imprisoned on the steps of the mosque, where everyone on their way to worship must spit on her. The superintendent of the palace gardens, with fantastic timing, happens to be in the area each time a baby comes floating along the river. He realizes that they must have come from the queen's apartments, but decides it's better not to get involved, and just raises them as his own. He and his wife pass away before they have the chance to explain the children's true origins, so the king's children - Bahman, Perviz and Periezade - are left to live in their isolated house, living a wealthy and comfortable yet solitary life. The boys are named after Persian kings - Perviz's name means "victorious" and I found out that one of the real Khosraus had "Parviz" as a byname. Periezade's name is derived from "peri" or fairy. The narrator takes note that Periezade is formally educated and physically active just as much as her brothers. One day, an old woman tells Periezade of three marvelous treasures: Speaking Bird, the Singing Tree, and the Golden Water. Periezade is overcome with longing for these things (I had forgotten before I reread it how weirdly obsessed she becomes). She pleads so much that her oldest brother Bahman agrees to go and find them, leaving behind a magical dagger that will become covered in blood if he dies. Soon enough the dagger turns bloody, and Perviz does the same, leaving Periezade with a string of pearls that will get stuck if he's in danger. When Perviz also falls into peril, Periezade disguises herself as a boy and sets out after them. Now, both Bahman and Perviz had encountered an old man on their journey, and Periezade soon does the same. In many stories, when a trio of siblings encounters an old beggar in the woods, it's a chance to contrast the nobler and kinder youngest sibling. However, in this case all three siblings are courteous and generous to the old man who warns them of the dangers ahead. The difference is in how they take his warning into account. He tells them that as they climb the mountain to the Speaking Bird, they must not turn back, even though voices will taunt or frighten them. The brothers each climbed the hill, filled with over-confidence, and end up turning around only to be transformed into black stones. Periezade, however, has the practical foresight and self-knowledge to stuff her ears with cotton. Not only does she get the bird, but it tells her how to restore her brothers and all the other travelers to life with the magical Golden Water. They return home with the treasures, and it so happens that the king encounters the brothers while they're hunting in the forest. They invite him to dinner. The Speaking Bird advises Periezade to serve a cucumber stuffed with pearls. Baffled, the king says that it makes no sense, and the Speaking Bird tells him that it makes just as much sense as a woman giving birth to animals. The Bird reveals the whole backstory, and the king embraces his long-lost children, sends the wicked sisters to be executed, and restores his queen to favor. (Even though I feel like a much more satisfying ending would be for her to take the kids and run far, far away.) Background Periezade's story is an example of Aarne-Thompson Type 707, "The Bird of Truth" or "The Golden Sons." Another version does appear in the Arabian Nights, known as "The Tale of the Sultan and his Sons and the Enchanting Birds." European versions are widespread. The persecuted wife accused of giving birth to animals, who is imprisoned but later restored to favor when her grown children return, is a very common motif that appears in all sorts of stories. Sometimes all of the children are boys. Sometimes it's twins, a boy and a girl, or a girl and several boys. Often, they are connected to stars or other celestial bodies, such as having a star on their foreheads. The blame on the queen in these stories hints that she indulged in bestiality to produce animal children, or she is responsible for bearing not a child but a molar pregnancy, disgracing her husband either way. The old woman who tells Periezade about the treasures remains mysterious. In some versions, it’s actually the wicked aunts or one of their servants, trying to get rid of the children now that they know they’ve survived. It seems this element was lost or confused in the Galland version. In some other tales, though, the old woman is a benevolent figure. Not all versions feature the quest for the magical objects, but the typical ending is that the king encounters the grown children - perhaps in the woods, perhaps at his own wedding to a second wife - and their story comes out, causing him to repent of his treatment to his wife. The story has ancient roots. A similar tale appeared around 1190 in Johannes de Alta Silva's Dolopathos sive de Rege et Septem Sapientibus. A lord marries a fairylike maiden who gives birth to septuplets, six boys and a girl, each born wearing a gold chain. The jealous mother-in-law swaps the children for puppies, and the easily fooled husband punishes his wife by having her buried up to the neck in the middle of the woods. The children survive and grow up in the forest; each has the power to transform into a swan, but the mother-in-law discovers them and steals the boys’ golden chains, leaving them trapped in swan form. The sister escapes this fate and continues to take care of her brothers, and when the lord finds out, he has the chains returned to his sons and frees them. (One son, whose chain was damaged, is left as a swan.) This is closer to the tale type of the Swan-Children, but there are still familiar elements. The more modern versions of "The Wild Swans," like Hans Christian Andersen's story, have the sister imprisoned, persecuted and accused of murdering her own children. Perhaps not incidentally, at the end she saves her brothers and regains her children at the same time, and is finally able to speak and tell her husband her whole backstory. The oldest known version of the Periezade variation is "Ancilotto, King of Provino," in The Facetious Nights of Straparola from the 1550s. The heroine is named Serena. This version has the quest as the villainous mother-in-law and aunts’ attempt to get rid of the children. The similarities in general are close enough that Galland might even have been directly influenced. Galland's contemporary, Madame D'Aulnoy, wrote her own version of the story as "Princess Belle-Etoile and the Prince Cheri." Sources

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed