|

Recently, when reading fantasy, I keep running into the idea that fairies cannot lie, only tell the truth. For this reason, they must use tricky language – literal truths disguising real meanings. For example, in Holly Black's novel Ironside, a fairy says that when she tries to lie, "I feel panicked and my mind starts racing, looking for a safe way to say it. I feel like I'm suffocating. My jaw just locks. I can't make any sound come out" (p. 56).

But is this really supported by older folklore? Deception seems inherent to the fairy way of life when you take into account, for instance, changelings. The core idea of changelings is that fairies are in disguise as your loved ones, pretending to be them. Why, then, is there an idea that fairies are truthful beings? Equivocating Language Trickery, loopholes, and "exact words" do play a significant part in fairytales. In the Irish tale "The Field of Boliauns," a man bullies a captive leprechaun into showing him where his gold is buried, under a particular boliaun (ragwort stalk) in a field. He doesn't have a shovel with him, so he ties a garter around the stalk and then makes the leprechaun swear not to touch it. He runs home to get the shovel, comes back, and finds that the leprechaun has taken his oath literally: he hasn't touched the garter, but has tied an identical garter around every single ragwort stalk in the field. Another case: a man carelessly trades with an otherworldly being in exchange for something which sounds inconsequential, but which turns out to be his own child. There's the giant who asks a king for "Nix, Nought, Nothing," which unbeknownst to the king is the name of his newborn son. The Grimms have "The Nixie in the Pond" with a water spirit asking for that which has just been born, and "The Girl Without Hands," where the Devil himself promises riches in exchange for what stands behind the mill; his target thinks he means an apple tree, but it's actually his daughter. This same kind of trick can happen in reverse, with a human fooling a fairy! In "The Farmer and the Boggart," a boggart lays claim to a certain farmer's field. The farmer convinces it to split the crop with him, and asks him if he would like "tops or bottoms." When the boggart says "bottoms," the farmer plants wheat, so that the boggart gets nothing but stubble. The next planting season, the infuriated boggart demands "tops" . . . so the farmer plants turnips. So we have the idea of tricky language in abundance. But what about an inability to lie? Fairies and Honesty According to John Rhys in Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx vol. 1, there are different classes of the Tylwyth Teg. Some are "honest and good towards mortals," while others are consummate thieves and cheats - swapping illusory money for real, and their own "wretched" offspring for human babies. They steal any milk, butter or cheese they can get their hands on. Going by context, honesty is referring to not stealing. In addition, the very dichotomy means fairies are not always honest. One term for the fairies, like the Good Folk or People of Peace, is the "Honest Folk" - daoine coire in Gaelic, and balti z'mones in Lithuanian. (Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, Volume 5) However, these names are essentially flattery meant to avoid fairy wrath. I would avoid taking these as literal descriptors. But if you keep going, in many traditions, the fae do prize honesty. In a Welsh tale recorded by the 12th-century writer Giraldus Cambrensis, a boy named Elidorus encounters "little men of pigmy stature" - pretty much fae. "They never took an oath, for they detested nothing so much as lies. As often as they returned from our upper hemisphere, they reprobated our ambition, infidelities, and inconstancies; they had no form of public worship, being strict lovers and reverers, as it seemed, of truth." However, this is not a "can't lie," but a "won't lie." It's a moral fable, for dishonesty is Elidorus' downfall. When he tells his mother of his adventures, she asks him to bring back "a present of gold." Her request could indicate greed, but it's also a challenge for Elidorus to prove that he's telling the truth. He steals a golden ball and takes it home. For this dishonesty, the pigmies immediately punish him: he is never able to find their realm again. The 12th-century Irish legend of “The Destruction of Da Derga's Hostel" features three riders all in red, on red horses. (Red is a common fairy color.) They are later identified as "[t]hree champions who wrought falsehood in the elfmounds. This is the punishment inflicted upon them by the king of the elfmounds, to be destroyed thrice by the King of Tara." In another legend from the same era, a man named Cormac visits the sea-god Manannan mac Lir and receives a golden cup which will break into three pieces if three words of falsehood are told nearby, and mend itself if three truths are told. As Walter Evans-Wentz summed it up in The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries, “respect for honesty” is a fairy trait in both ancient and contemporary Irish legends. Lady Wilde, in Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland, also referred to the fairies as "upright and honest" (at least in repaying debts). Another important piece of evidence is the tale of Thomas the Rhymer, with a story dating at least to a 14th-century romance. Even in the earliest versions, he is given the gift of prophecy by the fairy queen. In a later version recorded in Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802), when they part, she gives him an apple while saying "Take this for thy wages, True Thomas, It will give the tongue that can never lie." Thomas points out that this will be super inconvenient, but the fairy queen does not care. Here at last is the idea of being physically unable to lie - having a mouth and a tongue that are capable only of telling truth. However, the person with this quality is a human under a fairy's spell. There's a kind of mirror image in Giraldus Cambrensis' tale of Meilyr or Melerius, another prophet, who due to his close encounters with "unclean spirits" gains the ability to detect lies. Moving on: in many traditions, divine or otherworldly beings are swift to reward honesty and punish falsehood. See “The Rough-Face Girl” (Algonquin), “Our Lady’s Child” (German), and “The Honest Woodcutter” (from Aesop’s Fables). (Aesop uses the god Mercury, but other versions of the same story sometimes use a fairy.) In the book The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi (1883), Pinocchio repeatedly lies to the Blue Fairy, building on multiple falsehoods. With each lie, his nose grows, until finally it's so long that he gets stuck. The laughing Fairy "allowed the puppet to cry and to roar for a good half-hour over his nose... This she did to give him a severe lesson, and to correct him of the disgraceful fault of telling lies." Only after he has been sufficiently chastised does she restore him to normal. This is the fairy-as-moral-teacher who is so strongly present in 18th- and 19th-century literature, from French salon tales to Victorian children's books. In this era, fairies (particularly fairy godmothers) were strict parental figures who demanded honesty, fairness and goodness from humans. The Ideas Combine I think the seeds of the modern idea of fairies and falsehood come from the famed British folklorist Katharine Briggs. In The Fairies in Tradition and Literature (1967), Briggs recounted that "According to Elidurus the fairies were great lovers and respecters of truth, and indeed it is not wise to attempt to deceive them, nor will they ever tell a direct lie or break a direct promise, though they may often distort it. The Devil himself is more apt to prevaricate than to lie..." (pp. 131-132). There are a couple of different things to take from this. One is that not only do fairies not lie, but it's equally important for humans to be honest with them. "To tell lies to devils, ghosts or fairies was to put oneself into their power" (pp. 222-223). Also, it is clear that at least one of her main sources for this theme is Elidurus. She referenced Elidurus again in Dictionary of Fairies (1971), where she mentions again that fairies "seem to have a disinterested love" of truth, and that it is unwise to lie to them, although they may use tricky language themselves. She is summarizing based on a combination of two tale types - one where fairies value honesty, and one where they trick and evade. I have been collecting examples of books where fairies speak only truth. The earliest example so far is the children's book series Circle of Magic by James MacDonald and Debra Doyle. All six books were published in 1990. In this world, wizards cannot lie or they will corrupt their own power, but it is possible to use misleading language. The restriction is strongest for the elves or fair folk. According to their ruler, the Erlking: "You [a wizard] cannot speak an untruth and expect magic to serve you truly thereafter. Here magic is purer, and far more strict a master. A mortal wizard can sometimes break the words of a promise in order to keep its spirit, but I cannot. If I say that I will do a thing, or that I will not do a thing - then I must do it, or leave it undone, exactly as the words were spoken." (The High King's Daughter, p. 22) The examples I've collected really pick up after the year 2000. In Buttercup Baby by Karen Fox (2001), the faery protagonist has physical difficulty with telling actual lies (p. 218). It's also a big theme in the Dresden Files, for instance Summer Knight by Jim Butcher (2002), where not only are faeries not "allowed" to lie, but they are "bound to fulfill a promise spoken thrice." (p. 194) In Holly Black's Tithe (2002), there is a brief mention of "no lies, no deception" in the realm of fairies. Black goes more in-depth with later books, starting with Valiant (2005), where fairies are physically incapable of falsehood. A running theme is that they covet humans' ability to tell outright falsehoods. Other examples: Melissa Marr's Wicked Lovely series and Cassandra Clare's Shadowhunters (both beginning 2007). Patricia Briggs' Mercy Thompson series hints that if fairies lie, something bad will happen to them. Holly Black frequently references and recommends Briggs' work (as in this tweet). Patricia Briggs (no relation) was also inspired by Katharine Briggs, mentioning her work in an interview here. Morgan Daimler's Guide to the Celtic Fair Folk (2017) is a recent compendium that cites Katharine Briggs when saying that fairies are "always strictly honest with their words." Conclusion The idea that fairies cannot lie is a creative modern twist, stemming from cautionary fables about honesty and from stories about using wordplay to get the upper hand. Katharine Briggs never says that fairies cannot lie. She says only that they do not lie, apparently out of a strict moral code. My current theory is that a semantic shift occurred sometime between The Fairies in Tradition and Literature in 1967 and the Circle of Magic series in 1990. This shows how fairy mythology is still growing and evolving today. In older tales, from the honest woodcutter who meets the god Mercury, to Elidurus, to Pinocchio, otherworldly beings - including fairies - deeply value honesty. But it’s not just that fairies may not (technically) lie to you. It’s that you shouldn’t lie to them. But unvarnished truth isn’t always the best idea either, if you read tales like "The Fairies’ Midwife" . . . Thus the importance of tactical wordplay. Do you have any other examples of stories on fairies' relationship with honesty? Share them in the comments! [Edit 1/14/21]: Another one for the list is a German tale, "The Silver Bell" (Das Silberglöckchen), found in Arndt’s Fairy Tales from the Isle of Rügen (1896). Arndt explains that "the little folks [Unterirdischen, literally Underground Ones] may not lie, but must keep their word and fulfil the promises they give, else they are at once changed into the nastiest beasts, toads, snakes, dung-beetles, wolves, lynxes, and monkeys, and have to crawl and rove about for a thousand years, ere they can be delivered; therefore they hate lies." As in the Irish examples, the fairies are physically capable of lying, but fear punishment; and honesty extends not only to telling the truth, but to oaths and other matters of honor. The exact source for this punishment remains unclear.

3 Comments

Is there such a thing in folklore as a fairy-human hybrid? What would they be called? What traits would they inherit? Or would they inheirt only one parent’s nature?

In Gilbert and Sullivahn's comic opera Iolanthe (1882), the hero is half-fairy . . . literally, with an immortal upper half but human legs. There are some problems. In a mid-nineteenth-century music hall song, "The Keeper of the Eddystone Light," the union of a man and a mermaid produces two fish and the narrator of the song. More seriously, the protagonist of Eloise McGraw's 1996 novel The Moorchild, is a half-fae with both human and "moorfolk" characteristics. But these are more modern spins. In fact, there is a basis in legend. In a widespread tale type, a human man encounters a beautiful woman whose species varies from story to story. She may be a fairy, a mermaid, a selkie, a swan maiden, or a Yuki-Onna. Or maybe it’s a human woman who meets an otherworldly man: a fairy knight, an incubus, a god, a prince cursed into bear form… etc. When the human spouse breaks some taboo, the otherworldly spouse flees. Lucky humans go on a quest and have a chance to win them back. Unlucky humans pine away, alone for the rest of their lives. But either way, quite often the couple has produced at least one child. I’m going to count mermaids among fairies here. Mermaids are essentially water fairies, and half the time when a man takes a fairy bride, she is somehow connected to water. Otherworldly Hybrids in Mythology The idea of a human/nonhuman hybrid is not new. Half-gods abound in Greek mythology. However, most are skilled warriors with no supernatural powers. The half-god Achilles gains invulnerability not through genetics, but through a ritual performed by his mother. A few, like Dionysus, are born as full gods. Heracles is an outlier, a human with super-strength, who ultimately becomes a full god. Over in Ireland, Cu Chulainn is the son of a god and a human woman. There are legends that Abe no Seimei of Japan was the son of a human and a kitsune named Kuzunoha, and that he inherited from his mother traits that made him a powerful magician. Similarly, in Arthurian legend Merlin the magician was supposed to derive his abilities from his parentage as the son of a human woman and a demon or spirit. According to Jacob Grimm in Teutonic Mythology, vol. 3 "From the Devil's commerce with witches proceeds no human offspring, but elvish beings, which are named dinger (things...), elbe, holden" who appear as butterflies, bumblebees, caterpillars, or worms. Grimm describes the holden acting as spirit familiars to aid the witches in their mischief. Nephilim, or giants, appear in the Bible as offspring of “the sons of God” and “the daughters of man.” Plenty of people have made much of this, suggesting that the Nephilim were born of angels with human women. I’ve also run into the idea that they were the offspring of God’s followers with pagan women. Throughout history, descent from a god and, later, descent from a fairy could be a bragging point, especially for rulers. In a tale from India, a man lures a solitary girl known as "the daughter of the god Shillong" from her cave dwelling to marry her. She escapes him, as fairy brides always do, but, the people of the area hail their children as "god kings." (Folk Tales of Assam) Option one: Offspring of humans with fairies are all human The 16th-century Swiss alchemist Paracelsus wrote about "undines" - feminine water-spirits who might take human husbands in order to gain their own souls. Any children of such a union, Paracelsus adds, will be human beings, because they inherit souls from their human fathers. There are numerous ballads and lais where women have children with "fairy knights." Sir Degare is the offspring of one such pairing, but doesn't seem overtly otherworldly. Similarly, the Yuki-onna of Japan may have children with a human husband in her stories, but they don't have any apparent tendencies towards ice and snow. Such unions could produce whole clans. In Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, John Rhys recounts a number of overlapping fairy bride tales. A fairy named Penelope or Penelop was the ancestress of the Pelling clan. A fairy named Bella was the ancestress of the Bellisians. A fairy’s daughter with a human, known as Pelisha, began the family known as Bellis, who hated to be reminded of their fairy ancestry, and frequently got into brawls on the subject. Another term was Belsiaid. The names suggest that these are all the same story heard from different sources. Option two: offspring show otherworldly traits Even if some half-fairy knights like Sir Degare show no overt fairy characteristics, that is not always the rule. In the medieval lai of Tydorel (whose name I keep reading as Ti-D-Bol), the titular character is the son of a fairy knight and a human queen. Tydorel's otherworldly origins are shown by his inability to sleep. A man who cannot sleep, the lai tells us, is not human. This tale had a darker counterpart in the story of Merlin, as well as those of Sir Gowther and Robert the Devil, whose fathers were demons. In these cases, their heritage makes them evil, but can be overcome. The original Oberon, in the tales of Huon of Bordeaux, was depicted as the son of Julius Caesar and a fairy woman sometimes identified as Morgan le Fay. So this Oberon is actually half fairy! But his otherworldly appearance - small size and incredible beauty - is not an inborn trait, but the result of a curse. He does do a lot of magical stuff, though, and is king over the fairy realm. According to Irish lore, Geróid 'Iarla was the son of the Earl of Desmond, who fell in love with the water-goddess-like Aine n'Chliar when he met her on the lake. It was a typical fairy bride marriage, but in this case, the taboo was that the Earl must never express wonder at his son's abilities. Geróid was able to leap in and out of a bottle. When his father exclaimed at it, Geróid immediately went to the lake, transformed into a goose, and swam away. There was another connected story where Geroid took a wife himself, and she also had to abide by taboos. This is a legend which grew up around the historical figure of Garrett, fourth Earl of Desmond, who is supposed to have disappeared in 1398. The collector, David Fitzgerald, also mentions a possible connected legend that the Fitzgeralds are web-footed, hinting at the idea that the descendants of a fairy marriage have bird characteristics. Jeremiah Curtin collected a tale, "Tom Moore and the Seal Woman," which ends with the mention of the fairy's children: "All the five children that she left had webs between their fingers and toes, half-way to the tips." However, this trait decreased with successive generations. In an equivalent tale recounted by Thomas Keightley, the children of a human and a sea-maiden "retained no vestiges of their marine origin, saving a thin web between their fingers, and a bend of their hands, resembling that of the fore paws of a seal; distinctions which characterise the descendants of the family to the present day." As far as fairy wives go, Melusine possibly takes the lead as the most prolific childbearer. She bore her husband ten sons, eight of whom had strange appearances.

Bear in mind that Melusine herself is half-fairy! Her story is full of repetitions and layers. Her experience with her husband is foreshadowed by that of her mother, the fairy Pressyne, and a human king. Both Melusine and Geroid are examples of a child of a fairy bride and a human who take after their fairy parent - so much so that they repeat the story in the next generation. Melusine's mother Pressyne bore triplet girls, which in that time would have been scandalous, hinting at marital infidelity. However, like Oberon, Melusine wasn't born with her visible fairy qualities; her form as a half-serpent creature is the result of a curse. She must marry a human, who must keep to certain rules, in order to break it. Some scholars have suggested that her sons' deformities are also created by that curse. In some versions, her youngest sons are apparently human, indicating that her curse has been fading over the years. This makes it all the more tragic when her husband fails her and she loses her chance at humanity. Sometimes fairies carried humans off to marry them, and their children would then presumably be half-fairies. in the German tale of "The Changeling of Spornitz," the little people or "Mönks" (manikins) carry off human children to ensure that "earthly beauty would not entirely die out among them." Similarly, a girl named Eilian is stolen away as a fairy's bride in a Welsh tale. However, nothing is said of what her child is like, other than that it requires ointment in its eyes to have true sight of the fairy world - but this is common in tales of human midwives caring for fairy babies. The child of a human/fairy marriage is often a culture hero. His parentage explains why he's such a great warrior. One Arapaho tale has two parts - one dealing with a woman who marries a star with tragic results, and the second part dealing with their son Star Boy, who becomes a culture hero. In a Maori tale from New Zealand, a mermaid named Pania marries a human and bears a son named Moremore, who is completely hairless. His name means "bald." This son becomes a taniwha (serpent) or a shark and guards the local seas. In a story recorded in More West Highland Tales by Campbell and McKay, a woman becomes pregnant apparently by a seal, reminiscent of selkie tales. She gives birth to a son "as hairy as a goat," whom she names MacCuain, the Son of the Sea. MacCuain sometimes goes into a horrible frenzy where his face is distorted, and plays a villainous role in the tale. In the fairytale “Hans the Mermaid’s Son,” the main character is the son of a human and a mermaid. This is part of the Young Giant folktale type; Hans is the size of a large grown man when still a child, and has prodigious strength. He lacks any kind of stereotypical mer-attributes, having instead supernatural strength and size. (There are many tales of this type; sometimes, for instance, the Young Giant is the child of a woman and a bear.) Note that Hans is difficult for both his mortal father and magical mother to handle. Option three: Offspring are normal humans, but inherit non-genetic otherworldly gifts In "The Thunder Spirit's Bride," a tale from Rwanda, the children of the Thunder Spirit and a mortal woman are taught by their father "how to travel through the air on flashes of lightning, and they had a much more exciting life than the children of the earth, who could only walk and run." The Mad Pranks and Merry Jests of Robin Goodfellow, was printed in 1628 but may have existed much earlier. Here Robin Goodfellow is the son of Oberon the fairy king and a human woman. Although a born prankster and a thief, Robin seems like a normal human - at least until Oberon reveals his parentage and grants him the ability to shapeshift. Oberon informs him, "By nature thou has cunning shifts, Which Ile increase with other gifts. Wish what thou wilt, thou shalt it have; And for to vex both fool and knave, Thou hast the power to change thy shape, To horse, to hog, to dog, to ape." The phrasing in these stories leaves it unclear whether their powers are genetic or the result of teaching. The children may or may not have inherent skills, but either way, they require their fairy parent's instruction in order to use them. There is one clear case where the children are apparently human, but learn fairy knowledge from their mother's teachings. Sir John Rhys recorded a Welsh tale of a fairy bride from the lake Llyn y Fan Fach. Her human husband was told never to strike her three times without cause, but over the years scolded or even just tapped her, and on the third time she vanished back into the lake - leaving three distraught sons, who often walked by the lake searching for her. And one day it worked - she appeared to her oldest son, Rhiwallon, and taught him and his brothers the art of healing, so that they became the famous Physicians of Myddfai. Child Abandonment and DNA Dominance Fairy wives hardly ever take their children along when they jump ship, but leave their husbands to care for any offspring they have. For practical story purposes, the children may remain so that they can tell their father what happened to their mother. In T. Crofton Croker's story of the Lady of Gollerus, the mermaid wife doesn't mean to abandon her children, but forgets them the moment she touches the water. (Despite this, her human husband never remarries and always insists that she must be being held against her will beneath the ocean, not understanding how she could possibly want to leave him or their children.) This indicates that these children, although nominally hybrids, belong to the human world. Their father’s DNA is dominant. In a gender-flipped version, where a human woman is captured by an otherwordly husband and escapes, she still leaves her kids with him. Francis James Child described different variations of a ballad with this theme. Sometimes the woman returns home with her children, but she may also leave them behind while she makes her escape, ignoring her husband when he tells her the children are crying for her. In one Danish version of "Agnes and the Merman," where when Agnes returns to the human world, her husband insists that they divide their five children evenly. In the worst custody arrangement of all time, the fifth one is split in half. (This is not the only tale where the supernatural husband turns violent towards their children when the mortal wife goes home; the same thing happens in an Italian tale called "The Satyr.") In another related ballad, the human woman has never seen her children, since they are always taken from her to live in the elf-hill. At the end, she is taken to the elf-hill and her children give her a drink which makes her forget her mortal life. But sometimes the wife, whether human or fairy, does take her children along. In “Story of a Bird-Woman,” from Siberia, a goose-maiden bore her human husband two “real human children", but when she grew homesick, she contrived to take her children along. She begged help from the geese, who "plucked their wings and stuck feathers on the children's sleeves," so that they were able to fly away with their mother. And according to Hasan el-Shamy in Folktales of Egypt, in a union between a man and a jinniyah, "children from such a marriage belong to the mother, never to their human father." John Rhys, in Celtic Folklore, mentions a man whose fairy wife and children vanished when he broke a promise by unknowingly touching iron. In a tale from the Orkneys, Gem-de-Lovely the mermaid marries a human and bears seven children, then takes the whole family along when she returns to the sea. However, her mother-in-law brands the youngest child with a cross, blocking the merfolk from ever touching him, and he grows up on land as a powerful soldier who fights in the Crusades and makes a good marriage. Gender Divide? In the story of Melusine, her mother Pressyne actually does take her daughters from a mixed marriage with her when she flees. However, in the next generation, Melusine leaves her sons with their father. In some versions she comes back to nurse those who are still babies. That doesn't change that in some way, daughters share their mother's nature and native realm, while sons share their father's. Maybe this is just because Melusine's sons are more distantly related to the fairy realm. But there's another example that bears it up. A romance of Richard the Lionheart explained his battle-prowess by saying that he was the son of a human king and a woman named Cassodorien, who had fairylike characteristics, echoing Melusine-style myths. In the story, when forced to attend Mass, Cassodorien flies out through the roof carrying her other son John and daughter Topyas. John falls and is injured, but Topyas is carried away with her mother and never seen again. Again - the son gets left behind, the daughter gets taken. One of my favorite movies is the 2014 Irish animated film, Song of the Sea, which features two children (a boy and a girl) born of a human-selkie union. The boy is human like his father, while the girl is a selkie like her mother. Conclusion Sometimes the offspring of a human-fairy marriage are hybrids - humans with a touch of fairy ancestry, like the webbed-fingered kids in the selkie tale. However, more often they are either one or the other: all human, or all fairy. They typically take after their father's side of the family, at least in European myth, but there are occasional hints that their inheritance might be based on gender. If it's a human with special attributes, it's often because their fairy parent taught them a skill. Sons are mentioned more frequently than daughters, and typically grow up to be great warriors or wise men. Divine or fairy heritage was used to establish political power or explain the backstory of a popular culture hero. Throughout history, incubi or gods were given as the fathers of figures like Seleucus, Plato, or Scipio the Elder. The houses of Lusignan and Plantagenet claimed ancestry from Melusine or her equivalent. On the other hand, an unpopular person might be accused of being the offspring of a demon. See Bishop Guichard of Troyes in 1308, rumored to be the son of a human woman with a "neton." Also recall the Bellis clan, who would fight anyone who brought up their fairy background. I don't think there is any commonly used name for these fairy hybrids- although I would love to hear if you've come across one. SOURCES

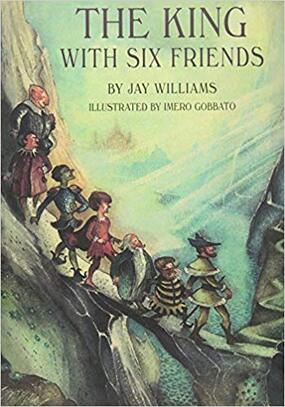

Further Reading This was one of my favorite fairytale books as a child. I still have my copy, although it's fraying and the spine is taped together. The illustrations have a dreamy, misty feel.

It follows a king who has lost his throne and crown, who goes out to wander the world. He encounters other travelers, who each have strange gifts. One can turn into an elephant, another into fire, and so on. They reach a kingdom where the king is offering his daughter's hand in marriage, but there are tests to complete. With the help of his extraordinary friends (the fire-man, for instance, devours an impossibly large feast), the lost king passes the tests and gains the princess's hand. This is ATU Type 513A, a widespread tale. The Grimms published one called "The Six Servants." It's fun particularly for the image of what would, in modern terms, be a team of superheroes. One fascinating early example is the Welsh tale of Culhwch and Olwen, possibly dated to around the 11th or 12th century. This is also one of the first existing stories connected with King Arthur. Culhwch's stepmother curses him so that the only woman he can marry is Olwen, beautiful daughter of a giant named Ysbaddaden. (This scene, with Olwen described as snowy and rosy-red, falls in with many stories where a prince seeks a bride as white as snow. Her ogre-like father needs his heavy eyebrows lifted up so he can see - another trope from those stories.) However, as it continues, Culhwch goes to his relative King Arthur for help. Because, of course, Ysbaddaden requires that several impossible tasks be completed before his daughter can marry anyone. This version abounds with mystical powers, so that Arthur's warriors resemble superheroes more than anything else. Cei (known better today as Sir Kay) can generate heat. A Welsh god, Gwyn ap Nudd, is among their number. The court list is prodigious. I do find it interesting that Arthur initially sends six of his warriors to scout things out when he hears of Culhwch's quest. Cei (who as mentioned is super hot), Bedwyr (who sheds blood faster than any other fighter), Kynddelig (an extraordinary guide), Gwrhyr (who knows all tongues), Gwalchmai (or Gawain, who always achieves his goals), and Menw (who can cast illusions and shapeshift into a bird). This is also the Greek myth of Jason and Medea. Jason captains the Argo, a ship crewed by gifted heroes and demigods. Medea is the villain's daughter who works magic and helps her lover flee. The King with Six Friends has an addition that is my favorite conclusion to this kind of tale. One might wonder why his friends don't get the kingdom and the princess, since they did all the work. And this is brought up in the text! But one of the friends responds, "He did what only a good king can do . . . He led us." |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed