|

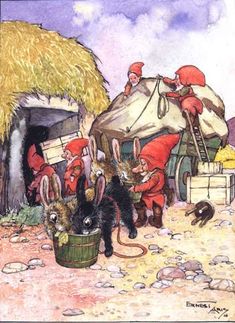

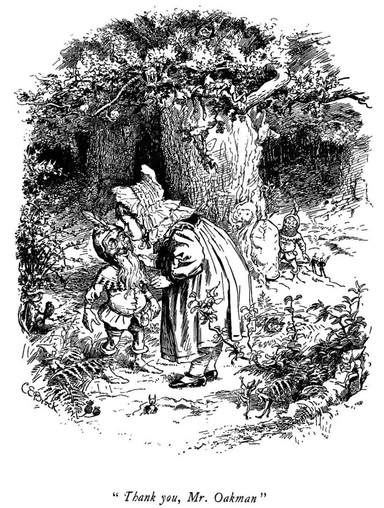

The oakmen are an English species of fairy, included by the famous folklorist Katharine Mary Briggs in her Dictionary of Fairies (1976). They are "squat, dwarfish people with red toadstool caps and red noses who tempt intruders into their copse with disguised food made of fungi." They inhabit a fairy wood where the ground is covered with bluebells. These are "sinister characters," she added in The Vanishing People (1978). Since then, oakmen have shown up fairly frequently in folklore encyclopedias and fantasy works (for instance, the One Ring RPG based on The Lord of the Rings). But the post "Oakmen Fairy Fakes?" at Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog raises some questions. Specifically: all of this rests on extremely flimsy evidence. Back up here for a second. Oaks have a long history in folklore and mythology. Fairy associations with trees, especially oaks, show up in Lewis Spence's British Fairy Origins (1946) and Jacob Grimm's Teutonic Mythology vol. 2, among many, many other books. In Reginald Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), "the man in the oke" appears in a list of supernatural beings. But K. M. Briggs isn't talking about any of that. She's describing oakmen, wee little English gnomes who live inside oak trees. And her sources are Ruth Tongue's Forgotten Folktales of the English Counties (1970) and Beatrix Potter's Fairy Caravan (1929). European folklore is clearly threaded through Potter's novel, and Briggs claimed hopefully, "It is probable that her Oakmen are founded on genuine traditions." By 1978 she was more certain. In The Vanishing People she wrote, "Although [The Fairy Caravan] makes no claim to be authoritative the legend is confirmed by the collections of Ruth Tongue." Ruth Tongue was Briggs' close friend and protégé. As usual, when recording the Cumberland story of "The Vixen and the Oakmen," she left her sources vague. This story was told by a nameless soldier stationed in the Lake District in 1948. Tongue's oakmen are tree-dwelling guardians of animals and nature, with no further description provided. There are several obscure fairy races which Tongue brought to light, seemingly out of nowhere, and which Briggs eagerly popularized - like the asrai. The oakmen fit the same patterns. Their story is strikingly unique, but there is one older work which could maybe hold evidence of a wider tradition (or evidence that Ruth Tongue took a little inspiration from books). "The Vixen" showcases her signature flowery style. It's the kind of story where talking animals chat about dinner plans. However, in this case, Briggs relied more strongly on Beatrix Potter as a source. The Fairy Caravan, the longest of Potter's works, follows a guinea pig who runs away and joins a secret animal circus. The watercolor landscapes are based on the Lake District (and hey, isn't that where "The Vixen and the Oakmen" was collected?). Potter's oakmen are “dwarfy red-capped figures” spotted pushing a miniature wheelbarrow through a glade. One is named Huddikin, like the Hödekin of German folklore. They are surprisingly mundane little people who take in animals during the winter. In an unrelated subplot, the characters search for a lost companion, Paddy Pig, who has vanished in Pringle Wood. This is a small wood of oaks where anyone who travels becomes lost and it is unwise to eat anything that grows. The ground is carpeted with bluebells, and the illustration shows tiny sprites hiding amidst the flowers. Someone eventually finds Paddy Pig inside a hollow tree, hallucinating after eating "tartlets" which were actually toadstools. While recovering, he describes being chased through the woods by “green things with red noses” that pinched him. The oakmen are never connected to the "green things with red noses." They have nothing to do with bluebells, poisonous fungi, Pringle Wood or any of the beings that live in it. They are not "sinister." They don't even wear toadstool caps - instead, they have pointed garden-gnome-style hats. Something has gone very wrong here. Upon some research, I quickly learned that this whole thing began when Beatrix Potter visited her new husband's seven-year-old niece, Nancy Nicholson. She was delighted by the little girl's imaginative stories of playing in the woods with the Oakmen. For Christmas in 1916, she gave Nancy a six-page watercolor-illustrated story about them. Here, the oakmen are jolly little fellows who live in larch trees (!) with little doors and windows. They are friends to both animals and humans. Their idyllic existence features tea parties sitting around toadstool-tables. When their forest is cut down, they move to a new home close to Potter's house. Potter was interested in publishing "The Oakmen" as her next book. Due to her failing eyesight, she began some preliminary work with an illustrator named Ernest A. Aris. However, when she started drafting, she learned that the oakmen were not Nancy's original creation. Instead, the idea may have come from a storybook which someone had read to her when she was little. Potter's biographers generally agree that she ended her plans for the oakmen over copyright concerns. In addition, she had a falling out with Aris over accusations that he had plagiarized her books. So the story was laid aside, but Potter had fond memories of the oakmen. In a 1924 letter, she lamented "I should have liked to have made a book of some of my 'letters to Nancy.'" And in 1929, she mentioned them briefly in The Fairy Caravan. This was not the story she had developed with Nancy, so perhaps she felt she had sidestepped any copyright problems. One character starts to talk about the Oakmen but swiftly changes the subject. You can read the original Oakmen story in Leslie Linder's History of the Writings of Beatrix Potter. As for Ernest A. Aris, he went on to include elves identical to Potter's oakmen in multiple picture books. It looks like there was something to those accusations of plagiarism. So the question is: where did Nancy Nicholson get the oakmen? Nancy later wrote of her friendship with Potter, "The oak-men were imaginary people who lived in trees, and I remember my amazement on my first visit to Sawrey, when this new aunt left the grown-ups and came to me to imagine windows and doors in the trees with people peeping out." Interestingly, she hyphenates it as oak-men, not like Potter's portmanteau Oakmen. After some more research, I have a hypothesis as to what inspired her. William Canton (1845-1926) was a British author who wrote several children's books inspired by his daughter Winifred Vida, or W.V. Some of these books mention Oak-men (with a hyphen!). These began as stories Canton told his daughter while they went for walks in the woods. They built their own fairytale world, ranging from the ominous Webs of the Iron Spider to the Oak-men's "small Gothic doors" in the trees. The Oak-men were small beings who drank out of acorn cups and wore clothes the color of leaves. W. V.: Her Book (1896), published when she was five years old, features a scene where W.V. gets lost in the woods. Fortunately, "the door of an oak-tree open[s] and a little, little, wee man all dressed in green, with green boots and a green feather in his cap, come[s] out.” This Oak-man and his friends help her find her way home. The story is accompanied by an illustration of the little girl in the midst of the trees, which all have little doors at their bases. She thanks one Oak-man with a kiss, while other Oak-men, pixies and animals stand by. (pp. 79-81) Oak-men also featured in A Child's Book of Saints (1898) and In memory of W. V. (1901). Tragically, ten-year-old W.V. died in 1901.

One of these could be the storybook Nancy read. Her tiny doors in trees and her use of a hyphen are Canton-esque, and she might have identified with the figure of little W.V. wandering the woods. These books also would have been recent enough to make Beatrix Potter's publishers really concerned. William Canton was well-acquainted with mythology and his daughter's games often featured fairies and pixies. However, it seems likely that the oak-men were not folk-fairies, but an original creation of the Canton family. Briggs treated Beatrix Potter like an author adapting a myth, but evidence shows that Potter behaved more like an author concerned about copyright infringement. That issue would never exist if oakmen were from folklore. It looks like this is a case of K. M. Briggs focusing on entertainment over accuracy. Although there is plenty of material connecting fairy beings to oak trees, she included the oakmen based on scanty evidence. Not only that, but she completely misread her source. The oakmen do not wear mushroom caps, glamour toadstools to look like tarts, or live in a bluebell-filled wood. Even if there are oakmen hiding in older English folklore, Briggs' description is fundamentally incorrect. Sources

3 Comments

That's the cover of a recent picture book retelling the fairytale with a Halloween theme. However, it reminded me of one of the first known mentions of Tom Thumb.

In Reginald Scot's 1584 work, the Discoverie of Witchcraft, he writes: “...they have so fraied us with bull beggers, spirits, witches . . . the puckle, Tom thombe, hob gobblin, Tom tumbler, boneles . . . and other such bugs, that we are afraid of our owne shadows.” What's Tom Thumb doing in a list of monsters? This baffled me for a long time, but then I looked at the first existing version of the story, "The History of Tom Thumbe," printed in 1621. A childless woman goes to Merlin for help. In this chapbook, Merlin is heavily associated with the occult, and is called (among other things) "a devil or spirit" who "consorts with Elves and Fairies." He tells the woman: Ere thrice the Moone her brightnes change A shapelesse child by wonder strange, Shall come abortive from thy wombe, No bigger then thy Husbands Thumbe: And as desire hath him begot, He shall have life, but substance not; No blood, nor bones in him shall grow, Not seen, but when he pleaseth so: His shapeless shadow shall be such, You'll heare him speak, but not him touch. The metrical version of 1630 is very similar, with some of the same phrasing. These descriptions indicate a Tom Thumb who is not entirely a physical being. Also notice that he doesn't have bones, and there's another demon on Scot's list named the Boneless. There's also a creature called the Tom Tumbler. Is this related to Tom Thumb, or is it just a readalike? On a close reading, the early versions of Tom Thumb contain many references to medieval European superstitions surrounding fairies, witches and demons. In addition to a close relationship with the fairies, Tom shows magical abilities in both of the 1621 and 1630 versions. For instance, he hangs pots and pans “upon a bright sun-beam” as a prank on his classmates. This motif occurs elsewhere in medieval legends. St. Goar of Treves miraculously hung his cape on a sunbeam, and St. Aicadrus did the same with his gloves. Later, Tom boasts that he can "creepe into a keyhole" and "saile in an egge-shel." Travel through keyholes was a common motif for witches, the devil, alps (nightmares), and other fairylike beings. Boating in an eggshell, too, was a popular witch/fairy pastime. Superstitious people would crush leftover eggshells so that these creatures couldn't set to sea in them. That's a post for another time, but eggshell-sailing witches appear even in Discoverie of Witchcraft - the same book that started this blog post. There are many mentions of Tom throughout the late 16th and early 17th centuries. I have a full list on my timeline page. In most of these brief mentions, Tom Thumb is simply a metaphor for something small. However, some give a hint of the story. In the shortened list here, seven works associate him with fairies and/or Robin Goodfellow. Five (possibly six) reference him being trapped in a pudding.

The Thumbling trapped inside food is a common motif which I've discussed before. While his mother is cooking, Tom falls into a pudding and gets boiled inside. In the prose version, the pudding shakes as if "the Devil and old Merlin" are trapped inside, until his mother believes it's bewitched. She hands it off to a passing tinker, who also thinks it must be the devil's work. Tom then breaks out of the pudding and runs home. "Dathera Dad," a Derbyshire tale published in 1895, consists of just this incident. The creature inside the pudding is "a little fairy child." Similarly, the Russian "Devil in the Dough Pan" has an evil spirit who is baked inside bread when a woman forgets to bless the dough. This was a common concept throughout Europe. In Scandinavia, peasant women made crosses on their dough to protect it from trolls (Thorpe 1851, pg. 275). The English did the same in order to "cross out" the witches, to "keep the devil from sitting on it," or to "let the devil out." Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology mentions a Somerset woman who would drew crosses on the cakes she baked, in order to stop the tiny, mischievous fairies from leaving footprints on them. The cross was also meant to make the bread rise faster. Perhaps there was a supernatural explanation of warding off evil spirits who might sit or step on the dough. This superstition was known in the 17th century, and perhaps as early as 1252, when King Henry III condemned bakers marking their bread with the sign of the cross. (Roud 2006) This could be connected to superstitions about demonic possession in the Early Middle Ages. Possession was often taken in a very literal, physical-minded way. Demons were depicted entering and leaving the victim's body via the mouth, or sometimes other orifices such as the ear. In his Dialogues, the late-6th-century pope St. Gregory the Great describes this case: "Upon a certain day, one of the Nuns of the same monastery, going into the garden, saw a lettice that liked her, and forgetting to bless it before with the sign of the cross, greedily did she eat it: whereupon she was suddenly possessed with the devil, fell down to the ground, and was pitifully tormented. Word in all haste was carried to [the bishop] Equitius, desiring him quickly to visit the afflicted woman, and to help her with his prayers: who so soon as he came into the garden, the devil that was entered began by her tongue, as it were, to excuse himself, saying: "What have I done? What have I done? I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." But the man of God in great zeal commanded him to depart." In both the story of the possessed lettuce and the superstitions about crossed bread, the idea is the same. When someone forgot to bless their food - by either praying over it or physically marking it - they became susceptible to any entities which might lurk within. Is this why Tom Thumb appeared in A Discoverie of Witches? Did Scot have demonic food in mind when he included Tom Thumb in the list? Or might he have encountered a version of the story which mentioned sailing in an eggshell? Maybe not. Still, the oldest surviving versions of the story contain allusions not only to magic and fairies, but to demonic activity and witchcraft. Further Reading:

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed