|

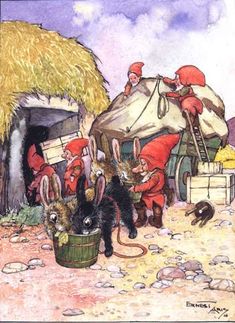

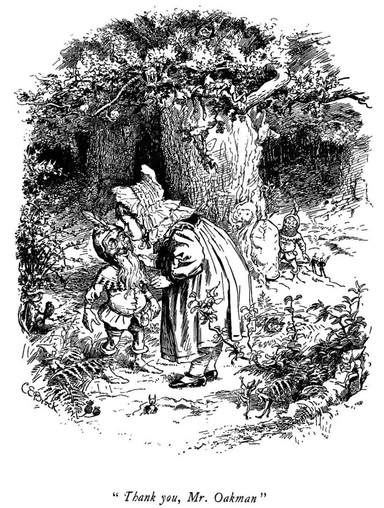

The oakmen are an English species of fairy, included by the famous folklorist Katharine Mary Briggs in her Dictionary of Fairies (1976). They are "squat, dwarfish people with red toadstool caps and red noses who tempt intruders into their copse with disguised food made of fungi." They inhabit a fairy wood where the ground is covered with bluebells. These are "sinister characters," she added in The Vanishing People (1978). Since then, oakmen have shown up fairly frequently in folklore encyclopedias and fantasy works (for instance, the One Ring RPG based on The Lord of the Rings). But the post "Oakmen Fairy Fakes?" at Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog raises some questions. Specifically: all of this rests on extremely flimsy evidence. Back up here for a second. Oaks have a long history in folklore and mythology. Fairy associations with trees, especially oaks, show up in Lewis Spence's British Fairy Origins (1946) and Jacob Grimm's Teutonic Mythology vol. 2, among many, many other books. In Reginald Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), "the man in the oke" appears in a list of supernatural beings. But K. M. Briggs isn't talking about any of that. She's describing oakmen, wee little English gnomes who live inside oak trees. And her sources are Ruth Tongue's Forgotten Folktales of the English Counties (1970) and Beatrix Potter's Fairy Caravan (1929). European folklore is clearly threaded through Potter's novel, and Briggs claimed hopefully, "It is probable that her Oakmen are founded on genuine traditions." By 1978 she was more certain. In The Vanishing People she wrote, "Although [The Fairy Caravan] makes no claim to be authoritative the legend is confirmed by the collections of Ruth Tongue." Ruth Tongue was Briggs' close friend and protégé. As usual, when recording the Cumberland story of "The Vixen and the Oakmen," she left her sources vague. This story was told by a nameless soldier stationed in the Lake District in 1948. Tongue's oakmen are tree-dwelling guardians of animals and nature, with no further description provided. There are several obscure fairy races which Tongue brought to light, seemingly out of nowhere, and which Briggs eagerly popularized - like the asrai. The oakmen fit the same patterns. Their story is strikingly unique, but there is one older work which could maybe hold evidence of a wider tradition (or evidence that Ruth Tongue took a little inspiration from books). "The Vixen" showcases her signature flowery style. It's the kind of story where talking animals chat about dinner plans. However, in this case, Briggs relied more strongly on Beatrix Potter as a source. The Fairy Caravan, the longest of Potter's works, follows a guinea pig who runs away and joins a secret animal circus. The watercolor landscapes are based on the Lake District (and hey, isn't that where "The Vixen and the Oakmen" was collected?). Potter's oakmen are “dwarfy red-capped figures” spotted pushing a miniature wheelbarrow through a glade. One is named Huddikin, like the Hödekin of German folklore. They are surprisingly mundane little people who take in animals during the winter. In an unrelated subplot, the characters search for a lost companion, Paddy Pig, who has vanished in Pringle Wood. This is a small wood of oaks where anyone who travels becomes lost and it is unwise to eat anything that grows. The ground is carpeted with bluebells, and the illustration shows tiny sprites hiding amidst the flowers. Someone eventually finds Paddy Pig inside a hollow tree, hallucinating after eating "tartlets" which were actually toadstools. While recovering, he describes being chased through the woods by “green things with red noses” that pinched him. The oakmen are never connected to the "green things with red noses." They have nothing to do with bluebells, poisonous fungi, Pringle Wood or any of the beings that live in it. They are not "sinister." They don't even wear toadstool caps - instead, they have pointed garden-gnome-style hats. Something has gone very wrong here. Upon some research, I quickly learned that this whole thing began when Beatrix Potter visited her new husband's seven-year-old niece, Nancy Nicholson. She was delighted by the little girl's imaginative stories of playing in the woods with the Oakmen. For Christmas in 1916, she gave Nancy a six-page watercolor-illustrated story about them. Here, the oakmen are jolly little fellows who live in larch trees (!) with little doors and windows. They are friends to both animals and humans. Their idyllic existence features tea parties sitting around toadstool-tables. When their forest is cut down, they move to a new home close to Potter's house. Potter was interested in publishing "The Oakmen" as her next book. Due to her failing eyesight, she began some preliminary work with an illustrator named Ernest A. Aris. However, when she started drafting, she learned that the oakmen were not Nancy's original creation. Instead, the idea may have come from a storybook which someone had read to her when she was little. Potter's biographers generally agree that she ended her plans for the oakmen over copyright concerns. In addition, she had a falling out with Aris over accusations that he had plagiarized her books. So the story was laid aside, but Potter had fond memories of the oakmen. In a 1924 letter, she lamented "I should have liked to have made a book of some of my 'letters to Nancy.'" And in 1929, she mentioned them briefly in The Fairy Caravan. This was not the story she had developed with Nancy, so perhaps she felt she had sidestepped any copyright problems. One character starts to talk about the Oakmen but swiftly changes the subject. You can read the original Oakmen story in Leslie Linder's History of the Writings of Beatrix Potter. As for Ernest A. Aris, he went on to include elves identical to Potter's oakmen in multiple picture books. It looks like there was something to those accusations of plagiarism. So the question is: where did Nancy Nicholson get the oakmen? Nancy later wrote of her friendship with Potter, "The oak-men were imaginary people who lived in trees, and I remember my amazement on my first visit to Sawrey, when this new aunt left the grown-ups and came to me to imagine windows and doors in the trees with people peeping out." Interestingly, she hyphenates it as oak-men, not like Potter's portmanteau Oakmen. After some more research, I have a hypothesis as to what inspired her. William Canton (1845-1926) was a British author who wrote several children's books inspired by his daughter Winifred Vida, or W.V. Some of these books mention Oak-men (with a hyphen!). These began as stories Canton told his daughter while they went for walks in the woods. They built their own fairytale world, ranging from the ominous Webs of the Iron Spider to the Oak-men's "small Gothic doors" in the trees. The Oak-men were small beings who drank out of acorn cups and wore clothes the color of leaves. W. V.: Her Book (1896), published when she was five years old, features a scene where W.V. gets lost in the woods. Fortunately, "the door of an oak-tree open[s] and a little, little, wee man all dressed in green, with green boots and a green feather in his cap, come[s] out.” This Oak-man and his friends help her find her way home. The story is accompanied by an illustration of the little girl in the midst of the trees, which all have little doors at their bases. She thanks one Oak-man with a kiss, while other Oak-men, pixies and animals stand by. (pp. 79-81) Oak-men also featured in A Child's Book of Saints (1898) and In memory of W. V. (1901). Tragically, ten-year-old W.V. died in 1901.

One of these could be the storybook Nancy read. Her tiny doors in trees and her use of a hyphen are Canton-esque, and she might have identified with the figure of little W.V. wandering the woods. These books also would have been recent enough to make Beatrix Potter's publishers really concerned. William Canton was well-acquainted with mythology and his daughter's games often featured fairies and pixies. However, it seems likely that the oak-men were not folk-fairies, but an original creation of the Canton family. Briggs treated Beatrix Potter like an author adapting a myth, but evidence shows that Potter behaved more like an author concerned about copyright infringement. That issue would never exist if oakmen were from folklore. It looks like this is a case of K. M. Briggs focusing on entertainment over accuracy. Although there is plenty of material connecting fairy beings to oak trees, she included the oakmen based on scanty evidence. Not only that, but she completely misread her source. The oakmen do not wear mushroom caps, glamour toadstools to look like tarts, or live in a bluebell-filled wood. Even if there are oakmen hiding in older English folklore, Briggs' description is fundamentally incorrect. Sources

Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

3 Comments

Ronan Coghlan

8/17/2020 10:42:12 am

Very interesting. I have Ruth Tongue's book, but I know enough to treat it with caution. May I ask who is actually running this website, which I have just discovered and find extremely impressive?

Reply

Writing in Margins

1/31/2022 07:47:48 am

That's very possible. Denham drew from Reginald Scot's list, mentioned in this blog post. Ruth Tongue was well-read and certainly aware of Denham's work. In her other books she gave detailed descriptions of the boneless, bull-beggar, and gallybeggar, all of which are named in the Denham Tracts. If there was an oral men-in-the-oak tradition that she heard... that's harder to say. Judging by the patterns of her work, one of Tongue's main methods was to borrow ideas from older works, and then use those older works as proof she'd recorded a "tradition."

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed