|

If you look up "cambion," you will most likely find sources telling you that this word refers to the offspring of a human and a demon - more specifically a succubus or incubus. But that's not what the word used to mean. Cambion comes from the Latin cambiare, to change. A cambion was originally a changeling.

This confusion isn't new. There are essentially two similar traditions of the Demon Baby, which have always been very close and prone to mixing up.

Today, cambions would be defined as Type 2. But when the 13th century bishop William of Auvergne mentioned cambiones in his work De Universo, he was describing Type 1. "You should not overlook what is said about infants whom the convention calls cambiones, about which the most widespread are old wives’ tales: that they are the children of demon incubi, substituted by female demons so that they are fed by them as if they are their own and are hence called cambiones, that is, cambici, as if swapped and substituted to female parents for their own children. They say that these are thin, always wailing, drinking so much milk that it takes four wet-nurses to feed one. They are seen to stay with their wet-nurses for many years, after which they fly away, or rather vanish." (Translation via Stainton and Goodey) William's "cambiones" are the offspring of incubi instead of fairies, but otherwise, they are the same. They eat, they scream, and they plague the families whose children they have replaced. In fact, Richard Firth Green remarks that "incubus" was “probably the most widely used general scholastic term for ‘fairy’ in the Middle Ages." (p. 3) William's account is one of the earliest full description of changelings. The common people would not actually have called them cambiones - that's Latin, so I'm not sure why William of Auvergne says it's a word of the "vulgar" or common tongue. Richard Firth Green in Elf Queens and Holy Friars: Fairy Beliefs and the Medieval Church has a detailed study of changelings in medieval belief. He gives a list of contemporary French and English names for this kind of creature: chamion, conjeoun or cangun. The word changeling did not show up until fairly late. The Oxford English Dictionary found it first in print around 1534. In 1487, the Malleus Maleficarum appeared on the scene. This was "The Hammer of Witches," a medieval book still infamous today. It was all about witchcraft and what people should do about it (spoiler: burn all the witches). It touched on the subject of demon-human hybrids a couple of times, but the part relevant to this discussion is Part 2, Chapter 8. "Another terrible thing which God permits to happen to men is when their own children are taken away from women, and strange children are put in their place by devils. And these children, which are commonly called changelings [campsores], or in the German tongue Wechselkinder, are of three kinds. For some are always ailing and crying, and yet the milk of four women is not enough to satisfy them. Some are generated by the operation of Incubus devils, of whom, however, they are not the sons, but of that man from whom the devil has received the semen as a Succubus, or whose semen he has collected from some nocturnal pollution in sleep. For these children are sometimes, by Divine permission, substituted for the real children. And there is a third kind, when the devils at times appear in the form of young children and attach themselves to the nurses. But all three kinds have this in common, that though they are very heavy, they are always ailing and do not grow, and cannot receive enough milk to satisfy them, and are often reported to have vanished away." This, and Martin Luther's "Table Talks" published in 1566, would become the most widely cited authorities on changelings (or in German: Kielkropf, Wechselkinder, or Wechselbälge). Luther's version would fit both Type 1 and Type 2, as they were the demonic children of Satan and human women, whom Satan then swapped for normal children. As Luther said, "This devil will suck and eat like an animal, but it will not grow. Thus it is said that changelings and killcrops do not live longer than eighteen or nineteen years." Less than a century later, Pierre de Lancre was a French judge and performer of a huge witch hunt. Among his books on witchcraft was Tableau de l'inconstance des mauvais anges et démons (1612). (Read it in English or French.) Like many of his contemporaries, he touches on the question of whether demons could procreate. He mentions cambions and, in describing them, cites Martin Luther and says that their "age is fixed at seven years." Despite specifically calling these children "changed children" (enfans Changes), he also seems pretty firm on the idea that these are "children born from sexual union with demons." Finally, he cites a story from the encyclopedic Dierum canicularum (Dog Days) by Simonis Majoli, which was printed in 1597. Although I have not been able to track down this tome, the story as de Lancre gives it runs like this. There was a beggar who always carried a little boy with him. The little boy never did anything but scream and cry. A horseman saw them trying to cross the river, and helpfully took the child onto his own horse, but the boy was so heavy that the horse nearly sank. The beggar later confessed that the boy was actually a demon with whom he had made a deal. As long as the beggar carried him around, everyone would give him alms. Later scholars would give this story significantly different spins, forget that it was Majoli or de Lancre who told it, and misspell de Lancre's name. The Dictionnaire Infernal by Jacques Auguste Simon Collin de Plancy, first published in 1818, includes the cambion but is rather misleading. It cites Delancre as saying that incubi and succubi produce children called cambions. This can imply that the cambions are born of incubi and succubi together, rather than an incubus-human or succubus-human relationship. The author repeats that Martin Luther said changelings lived seven years. This is clearly wrong, since Martin Luther talked about changelings living until eighteen or nineteen. De Plancy also includes the story of the beggar, but attributes it to Henri Boguet's Discours de Sorciers. (I cannot find the beggar's tale in that book at all, leading me to wonder if De Plancy misread De Lancre's citations.) The Dictionnaire's influence is seen as soon as 1861, when Dudley Costello published Holidays with Hobgoblins: And Talk of Strange Things. When he includes the beggar's tale, he describes the baby explicitly as a Cambion and the child of an incubus and succubus. Remember that de Lancre called it only a demon. Lewis Spence's Encyclopædia of Occultism (1920) also relied on the Dictionnaire Infernal. He defined cambions as "offspring of the incubi and succubi," citing Delamare. (Whoops.) All of the information is pretty much just a translation of the Dictionnaire. This new definition spread into popular culture. In Toilers of the Sea by Victor Hugo (1874), the main character is rumored to be a cambion, the son of a woman and the devil. One poem entitled "Cambion" in Clark Ashton Smith's The Dark Chateau (1951) runs "I am that spawn of witch and demon." Dungeons and Dragons brought out its Monster Manual II in 1983, with the demon-human-hybrid cambion. The evolution of the word is pretty clear, with both meanings having always twined around each other. There was overlap between fairies and demons as the Church demonized older traditions. The half-demon man was a common trope in medieval lore, like (again) Merlin or Robert the Devil or Sir Gowther. Some version of "cambion" was once an insult common to "bastard." There are other words out there for the same idea. For instance, Jakob Grimm's Teutonic Mythology vol. II (1844) says that the children of witches and devils are elves, Holds, or Holdiken. However, it's sobering to remember that many of these stories originated in trying to explain children born with congenital disorders. For instance, a severely disabled child whom Martin Luther saw and believed must be a demonic being deserving of death. Further Reading

1 Comment

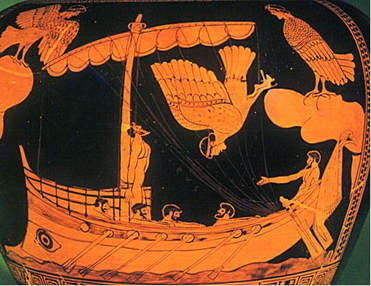

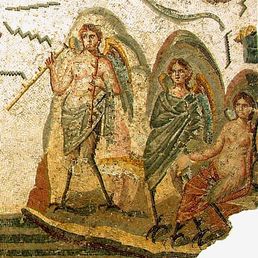

Sirens are not the same as mermaids. Mermaids are half-fish women, but sirens (the ones with the hypnotic singing voices) are half-bird women from Greek mythology. On the other hand, sirens and mermaids have been conflated for a long time. When did it begin? Sirens first appear in Homer's Odyssey in the 8th century B.C. Homer doesn’t really describe them at all. All we know is that their song will ensnare anyone who hears it. Later writers specify that sirens possess wings, or that they have the heads of beautiful women and bodies of birds. They may have drawn on Near Eastern myth-creatures like the ba of Egyptian cosmology. Human-faced birds were closely associated with the otherworld. Sirens mourned the dead in funerary art, and they were connected to Persephone, queen of the Underworld. Homer may have felt no need to describe sirens, since his audience would have known the context. Despoina Tsiafakis, however, suggests that the sirens could have gained avian attributes after Homer, when others sought to illustrate his work. (Tsiafakis p. 74) Meanwhile, fish-tailed people were a subject of art for a long time. They showed up in Mesopotamian art at least from the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC). These were usually men, like the god Ea, but fish-tailed women sometimes appeared. Then in medieval times, sirens stopped being bird-ladies and became fish-ladies. But birds and fish aren't typically interchangeable. What happened? Even in Ancient Greece, sirens were already evolving. Male sirens used to appear in art, but disappeared as artists' attitudes shifted (Tsiafakis). Now all female and anthropomorphized, sirens changed from monstrous birds with human heads to instrument-playing women who happened to have wings and bird feet. The emphasis moved to their beauty and allure. In some late Greek art they appeared as women with no avian attributes at all (Harrison 1882). As the legend traveled abroad, things got even more complicated. In his Commentary on Isaiah (c. 404-410 AD), Jerome uses siren as a translation for a couple of words. Regarding thennim (tannim, or jackals) he adds, "Moreover, sirens are called thennim (תנים), which we interpret as either demons, or some kind of monsters, or indeed great dragons, who are crested and fly." So now, apparently, sirens are dragons. This sets the stage for the next stage of sirens, where they are symbols of evil and temptation. In his Etymologies, compiled between c. 615 and the 630s, Isidore of Seville seems split on the issue. He tells us of "three Sirens who were part maidens, part birds, having wings and talons.” But he goes on to explain that “in Arabia there are snakes with wings, called sirens (sirena).” In the Liber monstrorum (Book of Monsters), from the late 7th-early 8th century, the anonymous author proposes "a little picture of a sea-girl or siren, which if it has a head of reason is followed by all kinds of shaggy and scaly tales.” Then there’s the Physiologus, a bestiary which originated as a 2nd-century Greek text. As pointed out by Wilfred P. Mustard, the original Physiologus doesn't mention sirens. However, translations varied widely and contradictions were rampant. In a 9th-century copy from Bern, even though the text described sirens as avian beings, a confused illustrator added an illustration of a half-serpent woman. (Dorofeeva 2014) A early 12th-century German edition gives Sirene as "meremanniu," and a Middle English translation "mereman." (Pakis 2010) Despite the discrepancies between editions, the Physiologus was a universally popular source for creators of medieval bestiaries. People later in this list, like Bartholomaeus and Geoffrey Chaucer, mentioned it by name when describing their siren-mermaids. Some authors seesawed on the subject. Guillame le Clerc, in his Bestiaire (c. 1210) said that the beautiful, murderous siren has the lower body of "a fish or a bird." Bartholomaeus Anglicus, in De proprietatibus rerum, “On the Properties of Things” (1240), was careful to cover all his bases. "The Mermayden, hyghte Sirena, is a see beaste wonderly shape," he said, and proceeded to describe fish-women, fowl-women, crested serpents, and pretty much everything in between. In quite a few illustrations, "transitional" sirens held sway. In the Northumberland Bestiary (c.1250-60), sirens are a kind of human-bird-fish hybrid with amphibious webbed feet. Or take this illustration, where the siren is a winged merperson. By the 14th century, the siren's identity had become standardized as a fish-tailed temptress with a hypnotic voice. The words siren and mermaid were interchangeable.

When Geoffrey Chaucer translated Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy, (1378-1381) he translated sirenae as meremaydenes. Then, in Nonne Preestes Tale (1387-1400), he described a "Song merier than the mermayde in the see." Male Regle (The Male Regimen) by Thomas Hoccleve (1406) "...spekth of meermaides in the see, How þat so inly mirie syngith shee that the shipman therwith fallith asleepe, And by hir aftir deuoured is he. From al swich song is good men hem to keepe." In Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene book II (1590s), "mermayds . . . making false melodies" tempt the heroes. These mermaids, Spenser explained, were once "fair ladies" but arrogantly challenged the "Heliconian maides" (the Greek Muses) and were turned to fish below the waist as punishment. (This sort of ties in with Pausanias’ Description of Greece from around the 2nd century A. D., where the Sirens and Muses had a singing competition. The Sirens lost and the Muses plucked out their feathers to make into crowns.) The original version of Sirens never fully went away. William Browne, in the Inner Temple Masque (1615) described Syrens "with their upper parts like women to the navell, and the rest like a hen." Still, sirens and mermaids remained generally synonymous, with few exceptions. English has the word mermaid for the fish-woman and siren for the mythological bird-woman. In Russian, too, the sirin has survived as a bird-woman. But in many other languages, “siren” is The Word for mermaid. According to Wilfred Mustard, "In French, Italian and Spanish literature, the Siren seems to have been always part fish." Languages that only use sirena or some variant for "mermaid" include Albanian, Basque, Bosnian, Croatian, French, Galician, Italian, Latvian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Serbian, Slovenian, and Spanish. Aquatic mammals like manatees and dugongs belong to the order Sirenia. A congenital disorder that causes children to be born with fused legs is called Sirenomelia. Sirens have always been associated with the ocean and with sailors. They are the children of a river god. It makes sense that people would portray them as part-fish. But could the change have been intentional, at least on some parts? Jane Harrison suggests that “the tail of an evil sea monster” was meant to emphasize the siren’s corruption and darkness (p. 169). The book Sea Enchantress: The Tale of the Mermaid and her Kin proposes that the intention was to give the beautiful sea-maiden “a graceful fish-tail, since a bird-body is hardly seductive in appearance” (p. 48). Different lines of thought there, but the same effect. Whatever caused this evolution, it's clear that the modern mermaid is truly the direct descendant of the ancient Greek siren. SOURCES

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed