|

Years ago, I wrote a blog post on the inspirations behind Hans Christian Andersen's "Thumbelina" (1835), examining a theory that the characters were influenced by people Andersen knew. And then I wrote another one a few years after that, focusing on the imagery of tiny flower fairies, which plays a big role in this fairytale. I want to revisit it this topic again and explore a little more deeply. It's always interesting to get into Andersen's writing process because these have become such classic fairytales and there are many different aspects to his stories. "The Little Mermaid," for instance, can be read as a semi-autobiographical tale of unrequited love, but also as Andersen's response to the hyper-popular mermaid story Undine, and also taking influence from other mermaid tales and tropes.

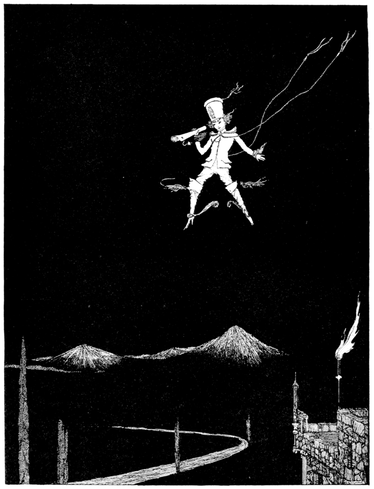

In "Thumbelina," a woman wishes for a little girl, and receives exactly that from a witch. The thumb-sized heroine is then kidnapped by a toad and deals with various talking animals who all want to marry her, until she winds up among fairies exactly her size and finally finds acceptance. Jeffrey and Diana Crone Frank compared Thumbelina to Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) and the short story Micromégas by Voltaire (1752). They also mentioned "the figure of a tiny girl" in one of Andersen's first successful publications, the 1829 story A Journey on Foot from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager. So far as I can tell, this character is the Lyrical Muse, a forlorn, melodramatic spirit of inspiration who appears to the narrator in Chapter 2. When the narrator tries to catch her, she shrinks into a tiny point and escapes through a keyhole. Similarly, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s stories “Princess Brambilla” (1820) and "Master Flea" (1822) both feature imagery of tiny princesses found sleeping inside lotuses or tulips. Hoffmann's work was widely popular in Europe, and in 1828, Andersen was part of a reading group named "The Serapion Brotherhood" after the title of Hoffmann's final book. There's also the Thumbling tale type. I'm sure Andersen came across many of these. There were the Thumbling stories collected by the Brothers Grimm, for instance. These actually do not have a lot in common with Thumbelina. There's the thumb-sized character, born from a wish, who's separated from his parents and swept off on an adventure, but the male Thumblings are typically more proactive and they ultimately return home to their parents. This is very different from Thumbelina, who never sees her mother again in the story, and whose story is something of a coming-of-age, concluding with her wedding and transformation of identity. These characters are also nearly always male. There are female Thumbling characters, but they've all been collected after Thumbelina, like a Spanish character I'd refer to as Garlic Girl (Maria como un Ajo, Cabecita de Ajo, or Baratxuri) and the Palestinian tale Nammūlah (Little Ant). It's more common to have tiny girl characters in other tale types. "Doll i’ the Grass," "Terra Camina," and "Nang Ut" are all examples of the Animal Bride tale, with their sister tales typically being about enchanted frogs, mice and so on. The Corsican "Ditu Migniulellu" is a variant of the Donkeyskin tale, a close neighbor to Cinderella. Thumbelina is the oldest example I've found of a female Thumbling character. Closer is "Tom Thumb," the first fairytale printed in English, and one of the earliest Thumbling variants we know of (depending when you date Issun-boshi). As I mentioned in my post on flower fairies, Tom Thumb was part of a wave of stories around the turn of the 17th century which transformed fairies into tiny, cute flower spirits, changed the face of the English concept of fairies, and has had far-reaching consequences pretty much everywhere. "Tom Thumb" is literary, like "Thumbelina." It gets into tiny detail, describing Tom's wardrobe of plant matter--a major part of the Jacobean flower fairy trope. He is the godson of the fairy queen and makes trips to Fairyland. This story really feels out-of-place among folk Thumbling tales, due to how altered it is - much like Thumbelina. And like Tom Thumb, Thumbelina gets detailed sequences describing her miniature life, like the way she uses a leaf for a boat. There's also a comparison in the way that Tom is accidentally separated from his parents when he's swooped up by a raven, while Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad. (For contrast, in a lot of Thumbling tales, the separation takes place when a human sees the thumb-child and tries to buy him.) The tiny, winged flower fairies whom Thumbelina meets are a direct descendant of the insect-sized, elaborately costumed Jacobean fairies that we meet in "Tom Thumb." Another Andersen tale, "The Steadfast Tin Soldier," also has a Tom Thumb-like bit where the main character is swallowed by a fish and freed when the fish is cut open for cooking. But in addition to Tom Thumb, there's a Danish story that Andersen may have encountered in some shape. This is "Svend Tomling," or Svend Thumbling, which was printed as a chapbook in 1776. Like Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, Svend Tomling is a literary tale. However, it's not focused on the cutesiness of the character; instead it's a lot more ribald, closer to the folk stories and veering off into satire. I'd really need someone fluent in Danish to give more in-depth examination, but my understanding is that like Thumbelina, Svend is created when a childless woman goes to a witch who gives her a magic flower. Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad and carried off in a nutshell; Svend is bought by a man who carries him off in a snuffbox. Thumbelina escapes and rides away on a lilypad drawn by a butterfly; Svend escapes and rides off on a pig. More importantly, Svend Tomling has themes that are unusual for a Thumbling story - a lot like Thumbelina. He contemplates marriage and faces the prospect of unsuitable partners. Thumbelina's suitors are her size, but the wrong species; the human women around Svend are the right species, but the wrong size. Even Issun-boshi feels a little different; it is a romance, but it doesn't feel quite as focused on considering the dilemmas and false matches and societal issues. There is a whole sequence where Svend sits down and debates with his parents about how to find an appropriate wife. Thumbelina faces criticism of her looks, advice on how to marry, and generally societal pressure on how she as a woman should be living her life. Thumbelina and Svend aren't the only Thumblings to assimilate and transform to fit into society (Thumbelina gets fairy wings to live with the fairies, Svend grows to human scale), but it does feel really key. Thumbling stories are often about childhood, albeit exaggerated so that the main character is not merely small but infinitesimal. Most thumbling stories end not with the hero finding a place for himself or getting married, but with him returning to his parents, the place where he still belongs. Tom Thumb dies at the end of his story, leaving him forever a child. Stories like Issun-boshi, where the character literally grows up and gets married, are rarer. References

Other Blog Posts

2 Comments

I first saw the news about this book being published a while ago and knew I had to pick it up. Issunboshi by Ryan Lang is an “epic graphic novel retelling” of the Japanese fairytale of Issunboshi, one of the most famous versions of ATU type 700. The publishing and printing were funded through Kickstarter. It took a while to get my hands on a copy, but here we are!

This retelling gives Issunboshi a more elaborate backstory. The gods used the Ame No Nuhoko, the Heavenly Spear, in the creation of the world. Afterwards, the spear was broken into four parts: the shaft, mount, blade, and spirit. One day an oni came across a piece of the spear. Gaining its power, he began collecting the other pieces and gathering a demon army with the goal of conquering the entire world. The spirit of the spear, searching for a way to stop things, found a childless couple who wished for a son even if he was only as tall as a thumb. The spirit took physical form as the tiny son they wished for, and they named him Issunboshi. The story proper starts with Issunboshi, now a young man six inches tall, living with his parents in their village. Although tiny, he’s stronger than most ordinary humans, and segues between riding on a pet owl or toting heavy buckets around. The story sets up Issunboshi’s feelings of inadequacy (he is approximately as tall as a toothbrush, after all) and his parents’ steady encouragement that he can be great. Then Issunboshi is kidnapped by a tengu or crow demon. Finding himself in the monster-haunted wilderness with only his old needle-sword for protection, he is rescued by a group of warriors who fight monsters and are preparing for a war against the Oni. Issunboshi’s new mentor tells him of his true past and begins training him for an epic confrontation. Issunboshi, small as he is, is the only one who can stop the oni from bringing on an apocalypse. This was a quick read with a simple, straightforward story. There are no big surprises from the plot, and characters don’t get a ton of depth or development. It’s tropey, or archetypal, or whatever you want to call it. There was some comic relief, but the jokes didn’t really land much. I did have a minor quibble with the theme. The book’s message, stated very clearly several times, is that even someone small can do great things (like save the world, fight a giant monster in a hand-to-hand battle, etc.). Although Issunboshi is small, he has near-godlike powers. His mentor tells him immediately that he’s the key to defeating the oni. Training montages and a stumble on the journey help offset this, but still feel quick or even rushed (a larger issue with the middle of the story, between a good beginning and ending). The message comes across okay, but it might have hit harder if Issunboshi wasn’t the amazingly strong incarnation of an all-powerful weapon, but just… a little guy. Ryan Lang is an animator and visual development artist who's worked at Disney and Dreamworks, and you can see that style strongly in his art here. Although everything is in grayscale, the characters are all very vibrant and expressive with unique designs. It also feels very cinematic, and the panels and word bubbles aren't always very dynamic, leaving the effect of storyboards or screenshots from an animated film. However, it is very pretty. There are lots of full-page splashes and spreads, showing off beautiful art. The book is advertised as epic, and it definitely pulls that off. The fairytale of Issun-boshi stands out among thumbling stories; it’s a coming-of-age tale, where Issun-boshi moves out of his parents’ home, finds a wife, and literally and metaphorically grows up—unlike most Western thumbling narratives, where the hero remains a child. I would say that Issun-boshi is, narratively speaking, one of the strongest and most compelling examples of ATU 700. Lang's graphic novel keeps the coming-of-age theme, but is focused on Issun-boshi’s clash with the oni. Instead of a chance encounter near the end of the story, this is a battle Issunboshi was always destined for. The book includes some pieces of concept art at the end, including one that looks like early drafts might have skewed closer to the original fairytale, with Issunboshi meeting a young noblewoman. There’s no romance or equivalent to that character in this retelling. Another big difference is replacing the magic hammer (uchide no kozuchi) of the fairy tale with the spear from an unrelated Shinto creation myth. There are echoes of some typical thumbling motifs, such as when Issunboshi is carried off by a bird or rides on a horse’s head. Overall, it was great to see a new adaptation of one of my favorite thumbling stories. While the story could be stronger, it’s still enjoyable and the art is fantastic. Definitely worth checking out. Further reading

A soldier's son sets out to make his fortune, saying goodbye to his widowed mother. On the way, he pulls a thorn from a tigress's paw; the grateful tigress, who happens to be able to talk, gives him a box in thanks and tells him to open it once he has carried it nine miles. However, the further he goes, the heavier the box becomes, until at eight and a quarter miles, it's impossible to carry. Saying that he believes the tigress was a witch, he throws the box down. The box bursts open, and out steps a little old man, one hath high (19 inches), with a beard that trails on the ground. The little man, who is highly cantankerous, is named Sir Buzz.

"Perhaps if you had carried it the full nine miles you might have found something better; but that's neither here nor there. I'm good enough for you, at any rate, and will serve you faithfully according to my mistress's orders." The soldier's son asks for dinner, and Sir Buzz immediately flashes away to the nearest town. There, he shouts at shopkeepers who don't notice him due to his size, and then leaves each shop with a massive bag of supplies, carrying them without any trouble. The soldier's son and Sir Buzz then eat a meal. Eventually the two reach the king's city, where the soldier's son sees the king's daughter, Princess Blossom. This princess is notable in that she weighs no more than the equivalent of five flowers. The soldier's son is smitten, and begs Sir Buzz to carry him to the princess. Although he complains, Sir Buzz - "who had a kind heart" - does so He takes him to the princess's bedchamber in the middle of the night. The princess is frightened at first, but is won over by the soldier's son, and the two talk all night and finally fall asleep at dawn. In order to prevent the soldier's son from being discovered, Sir Buzz carries off the bed with them both in it to a garden, uproots a tree to use as a club, and stands guard. As soon as it's noticed that the princess is missing, a huge search ensues. The one-eyed chief constable tries to search the garden, encounters a tiny screaming man waving a tree around, and returns to the king with this wholly original statement: "I am convinced your majesty's daughter, the Princess Blossom, is in your majesty's garden, just outside the town, as there is a tree there which fights terribly." Sir Buzz fights off anyone who tries to come near, and the soldier's son and Princess Blossom set off happily on their own. The soldier's son feels that he has made his fortune, and tells Sir Buzz that he can return to his mistress. However, Sir Buzz leaves him with a hair from his beard, telling him to burn it in the fire if he's ever in trouble. The princess and the soldier's son promptly get lost in a forest and reach the point of starvation. A Brahman invites them to his home, which is filled with riches. He tells them they may open any cupboard except the one locked with a golden key. Of course the soldier's son does so anyway, and in the forbidden cabinet finds a collection of human skulls. Their rescuer is not a Brahman, but a vampire who plans to eat them. At that very moment, the vampire steps in, but the quick-thinking Princess Blossom puts Sir Buzz's hair into the fire. Sir Buzz and the vampire then have a competition of transformations; the vampire turns into a dove and Sir Buzz into a hawk, and so on. The vampire becomes a rose in the lap of King Indra, and Sir Buzz becomes a musician who plays so wonderfully that Indra gives him the rose. Finally, the vampire turns into a mouse, and Sir Buzz becomes a cat and eats him. Sir Buzz then returns to Princess Blossom and the soldier's son and announces, "You two had better go home, for you are not fit to take care of yourselves." He takes them and all the vampire's riches back to the home of the hero's mother, where they live happily ever after, and Sir Buzz is never heard from again. This story has remained a favorite of mine because it's so colorful and silly. There's also a lot going on and all kinds of random details. Background The story was collected by Flora Annie Steel, a British woman whose husband worked in India in the Indian Civil Service. Steel published this story as "Sir Bumble" in the Indian Antiquary in 1881, and she wrote that the story was well-known in the Panjab and was "Muhammadan" in origin. It also appeared in her 1881 work Wide-Awake Stories: A Collection of Tales Told by Little children, between Sunset and Sunrise in the Panjab and Kashmir (1884). She changed the name to "Sir Buzz" in Tales of the Punjab: Told by the People (1894). The different versions are nearly identical. She wrote in the Indian Antiquary that "It possesses considerable literary merits remarkable from their absence in most Panjabi tales. The treatment is humorous and in places poetical, and the tale as a whole gives the idea of its having been at some period committed to writing." In Wide-Awake Stories, she stated she heard it from a Muslim Panjabi child, name unknown. The Tale Type and Characters The story falls into Aarne-Thompson type 562. Similar tales include "Aladdin" and Hans Christian Andersen's "The Tinderbox." In tales of type 562, a man seeking his fortune (often a former soldier, in this case the son of a soldier) encounters a sorcerer, witch, or someone else who gives them a magical object. This object grants them command of a magical servant - a genie, a giant, a gnome, or a trio of magic dogs. With this servant's help, the man kidnaps and marries a princess. Unfortunately, he gets into trouble and somehow loses access to the magical servant. At the last moment, he gets the servant back and everything works out. "Sir Buzz" has some unique touches. In many versions the sorcerer or witch is at odds with the hero, and the hero may even kill them to gain the magic source. But the tigress seems like a decent sort, and the hero willingly sends Sir Buzz back to her in the end. In most tales, the hero winds up becoming king when he marries the princess (sometimes executing her father in the process), but here the hero and princess return to his poor mother's home, and we never hear anything else about the kingdom. Heroes of Tale Type 562 tend to be jerks, but the hero of Sir Buzz is a hapless but honest type. There are some touches of other tales. The section in the vampire's house with the forbidden key is right out of "Bluebeard," and the finale of Sir Buzz's battle is similar to "Puss in Boots." According to Flora Annie Steel, the tigress was described in the original story as a bhut or evil spirit. Were-tigers feature in many Indian stories and could be dangerous villains. The tigress is unusual here in that she is apparently benevolent. The vampire, in the original, was a ghul, and Steel explains that the one eye of the chief constable (kotwal) indicates that he's evil. Princess Blossom's name is Bâdshâhzâdi Phûlî (Princess Flower) or Phûlâzâdî (Born-of-a-flower). Her unusual weight is a well-known motif in Indian folktales, known as the five-flower princess (Grounds for Play: The Nautanki Theatre of North India, p. 308). Her weight shows how delicate and almost otherworldly she is. We never hear of Princess Blossom's family or kingdom again. She does seem to be fairly capable and quick-thinking, though. Sir Buzz, the incredibly powerful, irritable and violent sprite, is clearly the star of the story. His personality stands out, which can be rare in this tale type. As well as being opinionated and a strong source of the slapstick comedy throughout the tale, he seems to have a genuinely caring relationship with the hero. His name is Mîyân Bhûngâ, which means "Sir Beetle" or "Sir Bumble-bee." The image of a tiny man with a long beard trailing on the ground is a common one, appearing in tales from across the world (a few are listed in my Thumbling Project here). A character with the exact same description is the tiny blacksmith in the story of Der Angule (Three-Inch), a Bengali Thumbling tale. Further reading You may have heard of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but have you ever heard of Svend Tomling?

Svend Tomling is the third oldest surviving thumbling tale, and is largely forgotten other than a few footnotes. Interestingly, its more famous predecessors, the Japanese Issun-Boshi and English Tom Thumb, are both fairly unique among thumbling tales. Issun-Boshi is one of the short stories and fairytales known as the Otogizōshi, written down mostly in the Muromachi period from 1392-1573. The exact date of Issun-Boshi's origin is unclear, but it's usually assigned to the 15th or 16th century. Japanese thumbling tales make up a unique subtype, with similarities to The Frog Prince. "Issun-boshi" is a romance in which a tiny, unassuming hero wins a princess for his bride, and then transforms into a handsome prince. The story still contains classic Thumbling motifs, and the story is surprisingly close to that of Tom Thumb all the way over in England. Issun-Boshi is born to an elderly couple who pray for a son; he uses a needle for a sword; he leaves home to serve an important nobleman. An oni, or demon, tries to swallow him, but Issun-Boshi escapes from his mouth alive. Tom Thumb is also of unclear original date, but at least we have dates for some important pieces of evidence. His name is mentioned in literature as early as 1579. A prose telling of the tale was printed in 1621, and a version in verse in 1630, although these are dated to the printing of the individual copy, not to the date of composition. The prose and metrical versions are very different, but hit most of the same beats. A childless couple turns to the wizard Merlin for help. Their son, who is born unusually quickly and of tiny size, wields a needle for a sword. He is swallowed in a mouthful of grass by a grazing cow, cries out from its belly, and is excreted. A giant tries to devour him. He is swallowed by a fish and discovered when someone catches it to cook it. He goes on to serve in King Arthur's court, then falls sick. Here the two editions diverge - the metrical version has him die of his illness and be grieved by the court, but the prose version has him recover when treated by the Pygmy King's personal physician, and go on to have other adventures including fighting fellow literary character Garagantua. Both of these stories are clearly thumbling stories, but they do not fit the usual map of Aarne-Thompson Type 700, a formulaic tale found consistently through Europe, Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. The Grimms were aware of this formula and actually published two thumbling stories. Their first was Thumbling's Travels, also a rather unusual example, but they later went back and added Daumesdick (Thumbthick, also translated as Thumbling), which better fit the pattern. A childless couple wishes for a son; he is only a thumb tall; he drives the plow by riding in the horse's ear, is sold as an oddity, escapes, has an encounter with robbers, is swallowed by animals, and finally returns home. Issun-Boshi, again, is part of a unique subtype. As for Tom Thumb, it's likely the subject of some literary embellishment, expanding a simpler traditional tale. Hints of the wider tradition peek through, like a scene where Tom returns home with a single penny and is welcomed by his parents. This is where many Type 700 stories end, but Tom Thumb instead keeps going. The traditional tale started really getting attention with the Grimms, but they were not the first ones to publish an example. The earliest surviving specimen is the Danish "Svend Tomling", or Svend Thumbling. Svend is a common men's name meaning "young man" or "young warrior," giving it the same generic feel as "Tom" in English. Both Svend Tomling and Tom Thumb essentially boil down to the same name of "Man Thumb," the way the name Jack Frost boils down to "Man Frost." Svend Tomling appears to have been the generic name for a thumbling in Denmark; it was also used for a Hop o' My Thumb type, which is an entirely different tale. The relevant version is a 1776 booklet by Hans Holck. It drew attention from the Danish historian Rasmus Nyerup, and from the Brothers Grimm. Nyerup, in particular, remembered reading or hearing the story as a child. The translation I've been working on is admittedly choppy, and I take responsibility if it's in error. "Svend Tomling" begins, as most thumbling stories do, with a childless couple. The wife goes to visit an enchantress and, upon instruction, eats two flowers. She then gives birth to Svend Tomling, who is born already clothed and carrying a sword. The section that follows is almost exactly the classic thumbling tale, with some unique details. Svend helps out on the farm by driving the plow, sitting in the horse's ear. A wealthy man witnesses this, purchases him from his parents, and carries Svend away (specifically, keeping him in his snuffbox). Svend escapes. Falling off their wagon, he lands on a pig's back and begins riding it like a horse. However, he is attacked by wild animals, and eventually the pig runs away. Lost in the middle of nowhere, Svend overhears two men plotting to rob the local deacon's house and asks to come along. He makes so much noise that he awakens the servants, and the thieves flee. There is a small divergence here, where the house owners think that Svend is a nisse (a Danish house spirit similar to the brownie) and leave out porridge for him. It doesn't take long before Svend is accidentally swallowed by a cow eating her hay. He calls out from inside her stomach to the milkmaid, who is frightened and thinks the cow is bewitched. Here's another divergence: people take this to mean that the cow can foretell the future, and flood to visit. This introduces a long monologue from a priest complaining about the peasants. Ultimately the cow is slaughtered. A sow eats the stomach in which Svend is still trapped, then poops him out. He falls into the water, where his own father happens to hear him crying out for help, and takes him home to recover. So far the plotline has been generally typical, but at this point, the story strikes out in its own direction. Svend announces that he wishes to take a wife. In particular, he wants to marry a woman three ells and three quarters tall. The length of an ell varied by country, but in Denmark, it was considered 25 inches. Svend Tomling is speaking of a wife who would be something like seven feet tall. His parents try to dissuade him, saying that he's far too small, and Svend grows frustrated. He begins bothering a "Troldqvinden" (a troll woman or witch) until she gets angry and transforms him into a goat. His horrified parents beg her to have mercy, and she relents and changes him into a well-grown man. The rest of the booklet (four pages out of the whole sixteen!) deals with Svend and his parents discussing his future, with questions of choosing an occupation and a bride, as he sets off into the world. Rasmus Nyerup took a pretty dim view of this story, remarking that great liberties had been taken with the folktale he remembered - particularly the priest's long speech about the problems with peasants, which has nothing to do with Svend Tomling. I suspect that the disproportionately long section on life advice is also original. The motif of eating two flowers and then giving birth to an unusual child is striking. This is exactly what happens in the story of King Lindworm (also Danish), where the resulting child is a lindworm and must be disenchanted. Also in Tatterhood (Norwegian), the queen who eats two flowers gives birth to a daughter, just as precocious as Svend, who rides out of the womb on a goat and carrying a spoon. Tom Thumb is usually listed as an influence on Hans Christian Andersen's Thumbelina. However, I think Svend Tomling might have been a stronger influence. If Rasmus Nyerup heard the story as a child, Andersen might have too. Both Svend Tomling and Thumbelina begin with a childless woman visiting a witch for help. Svend's mother eating flowers to conceive hearkens to Thumbelina being born from a flower. Both Svend and Thumbelina focus on the question of the character finding a fitting mate and a society that they fit into. Svend, like Thumbelina, is faced with incompatible mates, although for him these are ordinary human women, and for her, talking animals. Ultimately, otherworldly intervention transforms them to fit into their preferred society. Svend goes to a troll woman who makes him tall enough to seek a bride, while Thumbelina marries a flower fairy prince and gains wings like his. (Actually, Issun-Boshi did this too, getting a magical hammer from an oni and growing to average height.) Overall, Thumbelina has more in common with Svend Tomling and even Issun-Boshi than she does with Tom Thumb. The story itself is not all that great, but it does provide one of our earliest examples of the Thumbling story - and casts light on the others that followed. Sources

In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen published his fairytale “Tommelise,” or Thumbelina. A childless woman seeks help from a witch and receives a barleycorn. When planted, it grows into "a big, beautiful flower that looked just like a tulip" with "beautiful red and yellow petals." When it opens: "It was a tulip, sure enough, but in the middle of it, on a little green cushion, sat a tiny girl."

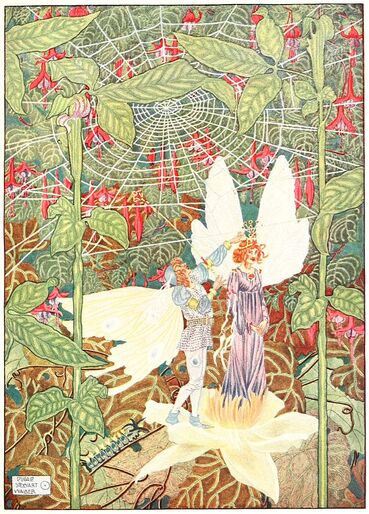

In "Thumbelina," Andersen took loose inspiration from older thumbling tales, but the heroine's birth from a flower is unusual. Some thumblings are created from a bean or other small object, but most often he or she is apparently born in the normal way, through pregnancy. Why did Andersen choose to write Thumbelina born from a flower - and what is the tulip's significance? Flower Fairies There's a widespread motif of fairies living in flowers. Andersen would have been well-aware of this trope. Thumbelina later encounters flower-angels (blomstens engels). They are evidently not quite the same species (winged and clear like glass, and dwelling in white flowers), but Thumbelina is happy enough to settle down with them. Another Andersen story, "The Rose Elf" (1839) also deals with tiny flower-dwelling spirits. The tiny flower fairy became popular around 1600. Shakespeare was an important influence; A Midsummer Night's Dream elves creep into acorn-cups to hide, and The Tempest's Ariel sings of lying inside a cowslip bell. In the anonymous play The Maid's Metamorphosis, a fairy sings of "leaping upon flowers' toppes". In the 1621 prose version of Tom Thumb, Tom falls asleep "upon the toppe of a Red Rose new blowne." In the 1627 poem Nymphidia, Queen Mab finds a "fair cowslip-flower" is a "fitting bower." What about older versions of the flower fairy? Greek mythology included dryads and other nature spirits, including the anthousai, or flower nymphs. Before Shakespeare, fairies in legends were generally child-sized at smallest - there are exceptions, such as the portunes of Gervase of Tilbury. Fairies, witches and other spirits were often said to ride in eggshells or crawl through keyholes. Fairies were held to live in nature and dance in "fairy circles" made of mushrooms or grass, or were encountered beneath trees. I'm also reminded of a 6th-century story recorded by Pope Gregory the Great, where a woman eats a lettuce which turns out to contain a demon. The demon complains, "I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." Superstitions held that demons might take up residence inside food if it wasn't properly blessed or protected with charms. Cowslips and foxgloves, already mentioned, were old fairy flowers. Cowslips are also known as fairy cups (Friend, Flower Lore), and foxgloves are fairy caps or as menyg ellyllon (goblin gloves). But these suggest very different scales. Flowers are hats and cups in language, but houses in literature. Katharine Briggs argued that Shakespeare did not originate the tiny flower fairy, but was inspired by contemporary tradition - however, there's not much evidence for this. Diane Purkiss took the exact opposite point of view, deeming it "questionable whether Shakespeare knew anything about fairies from oral sources at all," but I think this is an unnecessary leap. In more of a middle ground, Farah Karim-Cooper suggested that Shakespeare actually rescued fairies. In contemporary culture, they were being demonized, grouped with devils and witches and sorcery. Shakespeare made them benevolent but also tiny, therefore harmless and acceptable. In 1827, Blackwood's Magazine talked about Shakespeare's fairies and how they would "lodge in flower-cups, a hare-bell being a palace, a primrose a hall, an anemone a hut." I do not recall seeing these specific examples in Shakespeare, but this was now the popular perception. In the first 1828 edition of The Fairy Mythology, Thomas Keightley also talked about "the bells of flowers" as fairy habitations. "Oberon's Henchman; or the Legend of the Three Sisters," by M. G. Lewis (1803) describes fairies "Close hid in heather bells". In the poem “Song of the Fairies,” by Thomas Miller (1832), the fairies "sleep . . . in bright heath bells blue, From whence the bees their treasure drew," and then just in case we missed it, their "homes are hid in bells of flowers." Later in the same volume, a fairy named Violet "in a blue bell slept." Hartley Coleridge wrote of "Fays That sweetly nestle in the foxglove bells” (Poems, 1833) and Henry Gardner Adams had "The Elves that sleep in the Cowslip’s bell" (Flowers, 1844). The wood anemone was another fairy flower; at night the blossoms curled over like a tent, and "This was supposed to be the work of the fairies, who nestled inside the tent, and carefully pulled the curtains around them." (The Everyday Book of Natural History, 1866) This implies the existence of another explanatory legend. In a paper presented at a meeting of the New Jersey State Horticultural Society - yes - and published in 1881, the writer reminisced "I remember how I enjoyed the imaginary exploits of the little fairies that had their homes in these flowers. I had always thought it a pretty conceit to make the fairies live in flowers, but never thought how near the truth it is" . . . And then comes a leap to microorganisms. "A flower is a little universe with millions of inhabitants." Children's literature at the time was focused on edifying, providing morals, and providing scientific education. Fairy stories were considered a natural interest for children, and so they were often used to dress up school lessons, particularly on the natural world. They were a perfect way to launch into a lesson on insects or the world that could be found through a microscope. What about tulips specifically? David Lester Richardson's Flowers and Flower-Gardens (1855) mentions that "The Tulip is not endeared to us by many poetical associations." On the other hand, writing a century later, Katharine Briggs believed that the tulip was "a fairy flower according to folk tradition" and that it was a bad omen to cut or sell them. Taking a step back: in European thought, after the crash of the Dutch "tulip mania" in the 1630s, tulips generally became symbols of gaudiness and tastelessness, particularly in superficial female beauty - for instance, Abraham Cowley in 1656 writing "Thou Tulip, who thy stock in paint dost waste, Neither for Physick good, nor Smell, nor Taste." (Rees). As time passed, this faded into the background, but was not forgotten. David Lester Richardson wrote that tulips had remained extravagantly expensive, even in England, as late as 1836. There are a couple of 18th-century examples of tulip fairies. Thomas Tickell's poem "Kensington Garden" (1722) speaks of the fairies resembling a "moving Tulip-bed" and taking shelter in "a lofty Tulip's ample shade." In 1794, Thomas Blake's poem "Europe: A Prophecy" described a fairy seated "on a streak'd Tulip," singing of the pleasures of life. Intriguingly, in the same decade as Thumbelina, an early English folklorist named Anna Eliza Bray collected a story which also featured fairies within tulips. She recorded it in 1832 and published it in 1836, in A Description of the Part of Devonshire Bordering on the Tamar and the Tavy. The story follows an elderly gardener who discovers that the pixies have begun using her tulilps as cradles for her babies. She eventually dies. Her heirs rip up the flowerbed to plant parsley, but find that none of their vegetables will grow there. Meanwhile, the gardener's grave always mysteriously blooms with flowers. Bray does not give a specific source, other than to speak briefly of gathering the tales from village gossips and storytellers, with the assistance of her servant Mary Colling. Bray's pixie story was retold in fairytale collections and books of plant folklore. When she published a children's book, A Peep at the Pixies (1854), most of her focus in the introduction was on pixies’ small size relative to children; they could "creep through key-holes, and get into the bells of flowers." By the 20th century, the tulip as fairy flower was set. James Barrie wrote in The Little White Bird (1920) that white tulips are "fairy-cradles" (158), and Fifty Fairy Flower Legends by Caroline Silver June (1924), reveals that “Fairy cradles, fairy cradles, Are the Tulips red and white." Folklore In fact, fairies were not the only denizens of plants in legend. Birth from plants is very common in fairytales. English children were told that babies might be found in parsley beds, while in Germany, infants were more likely to be found among the cabbages or inside a hollow tree. (Curiosities of Indo-European Tradition and Folklore) In a French version, baby boys were found inside cabbages, baby girls inside roses. (e.g. Revue de Belgique, 1892, p. 227) Gooseberry bushes were also a likely spot. In Hindu culture and mythology, saying someone was born from a lotus was a way to indicate their purity. In Japanese stories, baby Momotaro is found inside a peach, and Princess Kaguya inside a bamboo. The Indian tale "Princess Aubergine" has a girl born from an eggplant. In the Kathāsaritsāgara (Ocean of the Streams of Stories), an 11th-century collection of Indian legends, Vinayavati is a heavenly maiden (divyā-kanyakā) who is born from the fruit of a jambu flower after a goddess in bee-form sheds a tear on it. In the Italian tale of "The Myrtle", from the Pentamerone (1634-1636), a woman gives birth to a sprig of myrtle. A fairy (fata) emerges from the plant each night, and a prince falls in love with her. However, the heroine is apparently of human scale, although she inhabits a plant not unlike a genie in a lamp. Later folklorist Italo Calvino collected more variants: "Rosemary" and "Apple Girl." The woman or fairy hidden within a luscious fruit appears in tale types such as "The Three Citrons." With the first known example of this story in The Pentamerone, there are probably as many variants of this story as there are types of fruit. In a close fairytale neighbor, a mother eats a flower to become pregnant - see the Norwegian "Tatterhood," the Danish "King Lindworm," and "Svend Tomling." "Tom Thumb" is usually cited as an influence on Thumbelina; in this story, a childless woman consults Merlin for help. Merlin prophesies her child's fate, she undergoes a very brief pregnancy, and then gives birth to a child one thumb tall. However, the two stories have little in common; the Thumbling tale type is widespread, and Andersen may have been inspired by other examples. The most likely candidate is "Svend Tomling," a chapbook written by Hans Holck and published in 1776. My translation is very choppy, but I think the gist is that a childless woman consults a witch. The witch causes two flowers to grow and instructs the woman to eat them. The woman then gives birth to Svend, one thumb high and already fully dressed and carrying a sword (beating out Tom Thumb, who has to wait several seconds for his wardrobe). I don't know for sure if Andersen knew this story, which hasn't achieved quite the same ubiquity as Tom Thumb. However, the fact that it was from his own country, and the similarities in Svend Tomling's and Tommelise's births, make a relationship seem likely. E. T. A. Hoffmann Fairytales weren't Andersen's only inspiration. One of his major influences was the fantasy/horror author E. T. A. Hoffmann (creator of The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, among other things). In Hoffmann’s “Princess Brambilla” (1820), a fairytale-esque subplot has the magician Hermod tasked with finding a new ruler for the kingdom. He causes a lotus to grow, and within its petals sleeps the baby Princess Mystilis. The person-inside-flower motif recurs throughout the story. Mystilis is later placed in the lotus to break a curse that has fallen on her, and emerges the second time as a giantess. Hermod himself is frequently seen seated inside a golden tulip. “Master Flea” (1822) has similar imagery. A scholar, studying a "beautiful lilac and yellow tulip," notices a speck inside the calyx. Under a magnifying glass, this speck turns out to be Princess Gamaheh, missing daughter of the Flower Queen, now microscopic and fast asleep in the pollen. Conclusion Andersen created his own thumbling tale inspired by folktales like that of Svend Tomling. However, he wove in plenty of elements in his own way - such as talking animals, or a girl born from a tulip. His work, including both "Thumbelina" and "The Rose-elf," shows the contemporary interest in fairies who lived inside flowers. Andersen's fairies in particular are most like personifications of plants. In the past, tulips had gained a bad reputation, becoming symbols of shallow frippery. However, by the time Andersen wrote, the disastrous tulip fad had had time to fade into history a little more. Instead, tulips started to be mentioned occasionally with fairies. In the 1800s, one author might have noted tales of tulip fairies as rare. However, a century later, Katharine Briggs could categorize it as a fairy flower. What changed? The most important thing may have been new associations for the tulip's shape; it was grouped in with other flowers that resembled bells or cups. I was startled when I went looking for examples of flower fairies - I occasionally found descriptions of them resting on top of the flowers, like Tom Thumb. However, more often than anything, I found the word "bell." Heather-bells, foxglove-bells, cowslip-bells, bluebells, bell-shaped flowers. In 1832, Thomas Miller's flower-fairy poem used the word bell three separate times. With fairies increasingly shrunken around Shakespeare's time, flowers that would have once been cups or hats were instead envisioned as houses or hiding places for fairies. The shape does suggest that something could be tucked inside, and lends itself to an air of mystery. Storytellers, including Andersen, focused on the idea of the hidden observer. Mary Botham Howitt wrote in 1852 "We could ourselves almost adopt the legend, and turning the leaves aside expect to meet the glance of tiny eyes." (George MacDonald used similar images, although with a more sinister slant, in his 1858 book Phantastes.) However, although Thumbelina's birth is still tied to the idea of flower fairies, it has more in common with tales of heroes born from plants. It is also strikingly reminiscent of E. T. A. Hoffmann's short stories; Hoffmann wrote twice of tiny princesses discovered inside flowers. In his work, tulips were not just gaudy or overly expensive, but had esoteric and mystical associations. His characters may be Thumbelina's clearest literary ancestors. Further Reading

Charles Perrault's fairytale "Le Petit Poucet" - literally "The Little Thumb," my preferred name for it being "Hop o' my Thumb" - has a lot to unpack. In one of the most memorable scenes, Hop o' my Thumb flees with his brothers while the ogre pursues them in seven-league boots. However, the ogre tires and falls asleep, and Hop steals the boots for himself. He goes on to use them as a royal messenger.

Seven-league boots (or as Perrault called them, "bottes de sept lieues," will allow the wearer to walk seven leagues in one step. A league was roughly the distance that a person could walk in one hour, so about three miles. Seven-league boots would thus carry you twenty-one miles at every stride. Seven is a number rich in symbolism and particularly recurrent in "Hop o' my Thumb." Hop is one of seven brothers. The ogre has seven daughters. This was not the first appearance of seven-league boots in Perrault's fairytales. In his version of Sleeping Beauty, there is a brief appearance by "a little dwarf who had a pair of seven-league boots, which are boots that enable one to cover seven leagues at a single step." This is where we actually learn what the boots do - "Le Petit Poucet" leaves the definition out. The dwarf in Sleeping Beauty even serves as a messenger, exactly the same vocation as Hop o' my Thumb. He is a bit character and most adaptations do not include him. Is this a cameo by Hop? Do Perrault's tales share a universe? And what drew Perrault more than once to this specific image, of the incredibly small man in the magic boots? The idea of magical footwear that enables people to travel incredible distances is a universal one, but it seems Perrault made up this particular variation. It spread quickly. In Finnish, they are "seitsemän peninkulman saappaat." In Russian, сапоги-скороходы (sapogi-skorokhody, or fast-walker boots). In German, they are siebenmeilenstiefel. In the Hungarian tale of "Zsuzska and the Devil" - basically a genderflip of Hop o' my Thumb - the heroine steals tengerlépő cipődet, or sea-striding shoes. "The Bee and the Orange Tree" by Madame d'Aulnoy and "Okerlo" by the Grimms feature seven-league boots and a chase scene. The Grimms' "Sweetheart Roland" includes meilenstiefel, literally "mile-boots." An African-American version of the story is "John and the Devil's Daughter," by Virginia Hamilton in The People Could Fly. The idea goes far back in history and mythology. In Greek mythology, of course, there are the Talaria, the winged sandals which allow the god Hermes to fly. In Chinese myth, there are the Ǒusībùyúnlǚ (Cloud-stepping Shoes), which allow the wearer to walk on the clouds. In the Irish tale of King Fergus, the luchorpain gives Fergus shoes that let him safely walk underwater or on water. In Teutonic Mythology, Jacob Grimm mentioned "gefeite schuhe" or "fairy shoes," "with which one could travel faster on the ground, and perhaps through the air." He directly compares these to Hermes' winged sandals and to the seven-league boots. In some versions, the magical traveling shoes are part of a set. In the 1621 version of Tom Thumb, Tom receives multiple gifts from his fairy godmother: a cap that bestows knowledge, a ring of invisibility, a girdle that enables shapeshifting, and finally “a payre of shooes, (that being on his feete) would in a moment carry him to any part of the earth, and to be any time where hee pleased.” In a brief scene, Tom dons the shoes and is "carried as quicke as thought" across the world to view anthropophages, cyclopes, and other monsters. "Jack the Giant-Killer" (1711) borrowed these elements, with Jack winning from a giant a coat of invisibility, a cap of knowledge, a fine sword, and "shoes of swiftness." This is similar to "The King of the Golden Mountain" (Grimm), where the hero tricks three giants into giving him a magic sword, a cloak of invisibility, and "a pair of boots which could transport the wearer to any place he wished in a moment." A similar tale is the Norwegian "Soria Moria Castle" (Asbjørnsen and Moe) with boots that make strides of twenty miles. In "The Iron Shoes," a Bavarian tale collected by Franz Xaver von Schonwerth, the hero's boots let him travel a hundred miles per step and run alongside the wind. There are a multitude of other examples. These objects are all common in legend and might originate in Greek mythology: the sandals of Hermes, the helm of Hades which grants invisibility, and the many transformations of Proteus. A mantle of invisibility belonging to King Arthur is mentioned in Culhwch and Olwen (c. 1100) and other Welsh myths. The tarnkappe - a similar object - plays a role in the Middle High German epic of the Nibelungenlied (c. 1200). Shapeshifting with or without the help of a magic object is a widespread trope throughout world mythology. The hero typically receives these magical tools from a supernatural force: he receives them from the gods or a fairy, or steals them from a monster. The ancestor of them all is the Greek hero Perseus. He is entrusted by the gods with the helm of invisibility and winged sandals, which he uses to slay Medusa the Gorgo. Hop o’ my Thumb bears absolutely no resemblance to the popular modern version of Tom Thumb - which is why it drives me nuts when people mix up the titles! However, there are a few similarities to the 1621 prose Tom Thumb.

Could Perrault have been inspired by Tom Thumb? Is that why he included an unusually small character wearing magic running shoes in two separate stories? Or did he take inspiration from the many other tales of magical shoes? In this case, I think it's very possible he was inspired by the 1621 Tom Thumb. The beginning of Hop o' my Thumb always struck me as a bit out of place; his nickname and implied supernatural state of birth are irrelevant to the story. It's almost as if they were imported from another tale . . . a tale closer to Tom Thumb. On a final note that interested me: unlike Perseus, Hop o’ my Thumb, and Jack the Giant-Killer, Tom Thumb does not use his magical tools to fight any monsters (although he has two run-ins with murderous giants). However, when traveling with his magic shoes, he does see monsters: "men without heads, their faces on their breasts, some with one legge, some with one eye in the forehead, some of one shape, some of another." Their presence serves to indicate just how far he has traveled. Monopods or sciapods are legendary people with only one leg. Blemmyae or akephaloi are headless men with their faces on their chests. Cyclopes or Arimaspi are beings with only one eye. They appeared in the work of Greek writers like Herodotus and Pliny the Elder. Their legends showed up in bestiaries and maps throughout the Middle Ages. Pliny the Elder placed cyclopes in Italy, blemmyae in North Africa, and monopods in India. Some bestiaries put the one-eyed "Arimaspians" in Scythia, in eastern Europe. So magical boots of travel are a very widespread and old idea, usually used in combination with other magical tools, but occasionally appearing on their own. They may have been Perrault's own creative touch. In tales similar to Hop o' my Thumb, there is frequently a chase where the hero must escape the villain, and does so by various means. Hansel and Gretel ride away on a duck. Other characters, like those in Sweetheart Roland, disguise themselves in a transformation chase. Perrault gave his hero magic boots for this scene, and codified them not just as magic boots but as seven-league boots (repeating the use of the number seven). Their presence, along with Petit Poucet's name, is fascinatingly reminiscent of the 1621 English Tom Thumb. What makes it even more interesting to me is that Perrault also used that Tom Thumb-esque character in Perrault's Sleeping Beauty. One classic fairytale is "Le Petit Poucet" by Charles Perrault - often translated in English as Hop o' My Thumb. A poor woodcutter and his wife, starving in poverty, decide to lighten their burden by abandoning their seven children in the woods. The youngest child, Hop o' my Thumb, attempts to mark the way home with a trail of breadcrumbs, but it's eaten by birds. The lost boys make their way to an ogre's house where they sleep for the night. The ogre prepares to kill them in their sleep; however, an alert Hop o' my Thumb switches the boys' nightcaps for the golden crowns worn by the ogre's seven daughters. While the ogre mistakenly slaughters his own children in the dark, the boys escape. Hop also manages to steal the ogre's seven league boots and treasure, ensuring his family will never starve again.

This tale is Aarne Thompson type 327B, "The Dwarf and the Giant" or "The Small Boy Defeats the Ogre." However, this title ignores the fact that there are stories where a girl fights the ogre, and that these stories are just as widespread and enduring. One ogre-fighting girl is the Scottish "Molly Whuppie." Three abandoned girls wind up at the home of a giant and his wife, who take them in for the night. The giant, plotting to eat the lost girls, places straw ropes around their necks and gold chains around the necks of his own daughters. Molly swaps the necklaces and, while the giant kills his own children, she and her sisters escape. Then, to win princely husbands for her sisters and herself, Molly sneaks back into the giant's house three times. Each time she steals marvelous treasures (much like Jack and the Beanstalk). At one point the giant captures her in a sack, but she tricks his wife into taking her place. She makes her final escape by running across a bridge of one hair, where the giant can't follow her. This tale was published by Joseph Jacobs; his source was the Aberdeenshire tale "Mally Whuppy." He rendered the story in standard English text and changed Mally to Molly. In Scottish, Whuppie or Whippy could be a contemptuous name for a disrespectful girl, but it was also an adjective for active, agile, or clever. This story probably originated with a near-identical tale from the isle of Islay: Maol a Chliobain or Maol a Mhoibean. J. F. Campbell, the collector, says that the spelling is phonetic but doesn't provide many clues to the meaning. Maol means, literally, bare or bald. Hannah Aitken pointed out that it could mean a devotee, a follower or servant who would have shaved their head in a tonsure. This word begins many Irish surnames, like Malcolm, meaning "devotee of St. Columba." When the story reached Aberdeenshire, the unfamiliar "Maol" became Mally or Molly, a nickname for Mary. According to Norman Macleod's Dictionary of the Gaelic Language, "moibean" is a mop. "Clib" is any dangling thing or the act of stumbling - leading to "clibein" or "cliobain," a hanging fold of loose skin, and "cliobaire," a clumsy person or a simpleton. Perhaps Maol a Chliobain means something like "Servant Simpleton" - a likely name for a despised youngest child in a fairytale. Maol a Mhoibean could mean something like "Servant Mop." There are a wealth of similar heroines. The Scottish Kitty Ill-Pretts is named for her cleverness, ill pretts being "nasty tricks." The Irish Hairy Rouchy and Hairy Rucky have rough appearances, and Máirín Rua is named for her red hair and beard (!). Another Irish tale with similar elements is Smallhead and the King's Sons, although this is more a confusion of different tales. The bridge of one hair which Molly/Mally crosses is a striking image. This perhaps emphasizes the heroine's smallness and lightness, in contrast to the giant's size. In "Maol a Chliobain," the hair comes from her own head. In "Smallhead and the King's Sons," it's the "Bridge of Blood," over which murderers cannot walk. Based on examples like these, Joseph Jacobs theorized that this tale was Celtic in origin. However, female variants of 327B span far beyond Celtic countries. Finette Cendron is a French literary tale by Madame d'Aulnoy, published in 1697, which blends into Cinderella. The heroine has multiple names - Fine-Oreille (Sharp-Ear), Finette (Cunning) and Cendron (Cinders). Zsuzska and the Devil is a Hungarian version. Zsuzska (whose name translates basically to "Susie") steals ocean-striding shoes from the devil, echoing Hop o' My Thumb's seven-league boots. According to Linda Dégh, female-led versions of AT 327B are quite popular in Hungary. Fatma the Beautiful is a fairly long tale from Sudan. In the central section, Fatma the Beautiful and her six companions are captured by an ogress. Fatma stays awake all night, preventing the ogress from eating them, and the group is able to escape and feed the ogress to a crocodile. In the ending section, the girls find husbands; Fatma wears the skin of an old man, only removing it to bathe, and her would-be husband must uncover her true identity. (This last motif seems to be common in tales from the African continent.) Christine Goldberg counted twelve versions of this tale in Africa and the Middle East. The Algerian tale of "Histoire de Moche et des sept petites filles," or The Story of Moche and the Seven Little Girls, features a youngest-daughter-hero named Aïcha. She combines traits of Hop o' my Thumb and Cinderella, and defends her older sisters from a monstrous cat. This is only one of many African and Middle Eastern tales of a girl named Aicha who fights monsters. And the tale has made its way to the Americas. Mutsmag and Muncimeg, in the Appalachians, are identical to Molly Whuppie. Meg is a typical girl's name, and I've seen theories that the "muts" in Mutsmag means "dirty" (making the name a similar construction to Cinderella). It could also be "muns," small, or from the Scottish "munsie," an "odd-looking or ridiculously-dressed person" (see McCarthy). German "mut" is bravery. (See a rundown of name theories here.) In the 1930s, "Belle Finette" was recorded in Missouri. Peg Bearskin is a variant from Newfoundland. In Old-Fashioned Fairy Tales (1882) by Juliana Horatia Ewing, we have "The Little Darner," where a young girl uses her darning skills to charm and manipulate an ogre. One of the largest differences between the male and female variants of 327B is the naming pattern. Male heroes of 327B are likely to be stunted in growth - a dwarf, a half-man, or a precocious newborn infant. Le Petit Poucet is "when born no bigger than one's thumb" - earning him his name. In English, he has been called Thumbling, Little Tom Thumb, or Hop o' My Thumb. The last name is my favorite, since it helps to distinguish him. Note that despite the confusion of names, he is not really a thumbling character. His size is only remarked upon at his birth. He is thumb-sized at birth, but in the story proper, he is apparently an unusually small but still perfectly normal child. Look at other similar heroes' names:

The names of girls who fight ogres focus on the heroine's intelligence or beauty (or lack of beauty). The heroine is often a youngest child, but I have never encountered a version where she's tiny, as Hop o' My Thumb is. The girl's appearance can play a role in the tale, but if so, the focus is usually on her being dirty, wild or hairy. Where the hero of 327B is shrunken and shrimpy, the heroine has a masculine appearance. Máirín Rua has a beard; Fatma the Beautiful disguises herself as an old man. Outside Type 327B, there are still other female characters who face trials similar to Hop o' my Thumb and Molly Whuppie. Aarne-Thompson 327A, "The Children and the Witch," includes "Hansel and Gretel" (German) and "Nennello and Nennella" (Italian). Nennello and Nennella mean something like "little dwarf boy and little dwarf girl." Nennella, with her name and her adventure being swallowed by a large fish, is the closest to a Thumbling character. Bâpkhâdi, in a tale from India, is born from a blister on her father's thumb - a birth similar to many thumbling stories. In the opening to the tale, her parents abandon her and her six older sisters in the woods. However, after this episode, the tale turns into Cinderella. In Aarne-Thompson type 711, the beautiful and the ugly twin, an ugly sister protects a more beautiful sister, fights otherworldly forces, and wins a husband. This encompasses the Norwegian "Tatterhood," Scottish "Katie Crackernuts," and French Canadian "La Poiluse." It overlaps with previously mentioned tales like Mairin Rua and Peg Bearskin. One central motif to 327B is the trick where the hero swaps clothes, beds, or another identifying object, so that the villain kills their own offspring by mistake. This motif appears in in many other tales, even ones with completely different plots. A girl plays this trick in a Lyela tale from Africa mentioned by Christine Goldberg. In fact, one of the oldest appearances of this motif appears in Greek myth. There, two women - Ino and Themisto - play the roles of trickster heroine and villain. Madame D’Aulnoy’s “The Bee and the Orange Tree” and the Grimms’ "Sweetheart Roland" and "Okerlo" are very similar to 327B. However, they are their own tale type, ATU 313 or “The Magic Flight.” In these tales, a young woman is always the one fighting off the witch or ogre. She’s the one who switches hats, steals magic tools, and rescues others. The main difference is that while the heroes of ATU 327 are lost children, the heroes of ATU 313 are young lovers. But back to the the basic 327B tale. Both "The Dwarf and the Giant" and "Small Boy Defeats the Ogre" are flawed names, given that stories where a girl defeats the ogre are so widespread. These ogre-slaying girls pop up in Ireland, Scotland, Hungary, France, Egypt, and Persia, and have thrived in the Americas. I fully expect to find more out there. Sources

Hi guys! Check out this podcast episode on "Thumbling as Journeyman" at https://grimmreading.podbean.com. The series goes through the tales of the Brothers Grimm, and in this episode they mention Writing in Margins.

That's the cover of a recent picture book retelling the fairytale with a Halloween theme. However, it reminded me of one of the first known mentions of Tom Thumb.

In Reginald Scot's 1584 work, the Discoverie of Witchcraft, he writes: “...they have so fraied us with bull beggers, spirits, witches . . . the puckle, Tom thombe, hob gobblin, Tom tumbler, boneles . . . and other such bugs, that we are afraid of our owne shadows.” What's Tom Thumb doing in a list of monsters? This baffled me for a long time, but then I looked at the first existing version of the story, "The History of Tom Thumbe," printed in 1621. A childless woman goes to Merlin for help. In this chapbook, Merlin is heavily associated with the occult, and is called (among other things) "a devil or spirit" who "consorts with Elves and Fairies." He tells the woman: Ere thrice the Moone her brightnes change A shapelesse child by wonder strange, Shall come abortive from thy wombe, No bigger then thy Husbands Thumbe: And as desire hath him begot, He shall have life, but substance not; No blood, nor bones in him shall grow, Not seen, but when he pleaseth so: His shapeless shadow shall be such, You'll heare him speak, but not him touch. The metrical version of 1630 is very similar, with some of the same phrasing. These descriptions indicate a Tom Thumb who is not entirely a physical being. Also notice that he doesn't have bones, and there's another demon on Scot's list named the Boneless. There's also a creature called the Tom Tumbler. Is this related to Tom Thumb, or is it just a readalike? On a close reading, the early versions of Tom Thumb contain many references to medieval European superstitions surrounding fairies, witches and demons. In addition to a close relationship with the fairies, Tom shows magical abilities in both of the 1621 and 1630 versions. For instance, he hangs pots and pans “upon a bright sun-beam” as a prank on his classmates. This motif occurs elsewhere in medieval legends. St. Goar of Treves miraculously hung his cape on a sunbeam, and St. Aicadrus did the same with his gloves. Later, Tom boasts that he can "creepe into a keyhole" and "saile in an egge-shel." Travel through keyholes was a common motif for witches, the devil, alps (nightmares), and other fairylike beings. Boating in an eggshell, too, was a popular witch/fairy pastime. Superstitious people would crush leftover eggshells so that these creatures couldn't set to sea in them. That's a post for another time, but eggshell-sailing witches appear even in Discoverie of Witchcraft - the same book that started this blog post. There are many mentions of Tom throughout the late 16th and early 17th centuries. I have a full list on my timeline page. In most of these brief mentions, Tom Thumb is simply a metaphor for something small. However, some give a hint of the story. In the shortened list here, seven works associate him with fairies and/or Robin Goodfellow. Five (possibly six) reference him being trapped in a pudding.

The Thumbling trapped inside food is a common motif which I've discussed before. While his mother is cooking, Tom falls into a pudding and gets boiled inside. In the prose version, the pudding shakes as if "the Devil and old Merlin" are trapped inside, until his mother believes it's bewitched. She hands it off to a passing tinker, who also thinks it must be the devil's work. Tom then breaks out of the pudding and runs home. "Dathera Dad," a Derbyshire tale published in 1895, consists of just this incident. The creature inside the pudding is "a little fairy child." Similarly, the Russian "Devil in the Dough Pan" has an evil spirit who is baked inside bread when a woman forgets to bless the dough. This was a common concept throughout Europe. In Scandinavia, peasant women made crosses on their dough to protect it from trolls (Thorpe 1851, pg. 275). The English did the same in order to "cross out" the witches, to "keep the devil from sitting on it," or to "let the devil out." Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology mentions a Somerset woman who would drew crosses on the cakes she baked, in order to stop the tiny, mischievous fairies from leaving footprints on them. The cross was also meant to make the bread rise faster. Perhaps there was a supernatural explanation of warding off evil spirits who might sit or step on the dough. This superstition was known in the 17th century, and perhaps as early as 1252, when King Henry III condemned bakers marking their bread with the sign of the cross. (Roud 2006) This could be connected to superstitions about demonic possession in the Early Middle Ages. Possession was often taken in a very literal, physical-minded way. Demons were depicted entering and leaving the victim's body via the mouth, or sometimes other orifices such as the ear. In his Dialogues, the late-6th-century pope St. Gregory the Great describes this case: "Upon a certain day, one of the Nuns of the same monastery, going into the garden, saw a lettice that liked her, and forgetting to bless it before with the sign of the cross, greedily did she eat it: whereupon she was suddenly possessed with the devil, fell down to the ground, and was pitifully tormented. Word in all haste was carried to [the bishop] Equitius, desiring him quickly to visit the afflicted woman, and to help her with his prayers: who so soon as he came into the garden, the devil that was entered began by her tongue, as it were, to excuse himself, saying: "What have I done? What have I done? I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." But the man of God in great zeal commanded him to depart." In both the story of the possessed lettuce and the superstitions about crossed bread, the idea is the same. When someone forgot to bless their food - by either praying over it or physically marking it - they became susceptible to any entities which might lurk within. Is this why Tom Thumb appeared in A Discoverie of Witches? Did Scot have demonic food in mind when he included Tom Thumb in the list? Or might he have encountered a version of the story which mentioned sailing in an eggshell? Maybe not. Still, the oldest surviving versions of the story contain allusions not only to magic and fairies, but to demonic activity and witchcraft. Further Reading:

There's a story about a tiny man who comes to the king's court. The man is so tiny that when he looks into a pot of porridge, he slips, falls in, and almost drowns. Sounds like Tom Thumb, right? Let's go back a little ways to an Irish tale - the Saga of Fergus mac Léti. This appears in the Senchas Már and its Old Irish glossings. The Senchas Már is a compilation of early Irish law texts from the 7th and 8th centuries. The brief poem about Fergus has to do with the restitution made after the murder of a slave, and mentions Fergus' own death by drowning. The Irish glossings of the 8th century (MSS TCD H.3.18 and Harlean 432) go into more depth. Some water-sprites (known as the "lúchorpáin," or "little bodies") try to drag the sleeping King Fergus into the sea. He wakes up and catches them. In exchange for their freedom, they give him three wishes, including the ability to breathe underwater. However, they tell him never to swim in Loch Rudraige (or Lockrury). One day he disobeys them and finds a sea monster there called Muirdris, which leaves him with a disfigured face. His court attempts to hide this, but the truth eventually comes out when a slave woman named Dorn tells him the truth. In his fury, Fergus kills her, then returns to the loch, where he and the monster both die in a battle that leaves the loch red with blood. Many scholars believe that this story of the lúchorpáin is the first mention of leprechauns. Flash forward to the Irish manuscript known as Egerton 1782. This was written in 1517-1518 by the scribes of the O'Mulconry family and includes over sixty tales, poems, and miscellania. Among the tales is an expanded version of the death of Fergus mac Leti. This is a longer, more comical and sexual version that names the rulers of the Lupra and Lupracan: King Iubdan (pronounced Uf-don) and Queen Bebo (Bay-voe).

One day, Iubdan holds a banquet. Bebo sits at his side. All his strongest warriors are there, including a great strongman who's mighty enough to chop down a thistle at one stroke. The ale flows, people make merry, and finally Iubdan stands up and begins to shout, "Have you ever seen a king greater than myself?" No, no, he's the greatest king, he has the mightiest warriors, the finest army the world has ever known. But suddenly, the king's chief poet Esirt bursts out laughing. An incensed Iubdan is all set to have him arrested, but Esirt tells him of the land of Emania, where the people are like giants to them. Iubdan's mighty army is worth peanuts by comparison. Esirt goes there to prove that he's right, and the people there are astonished by the "dwarf that could stand on full-sized men's hand." They carry him in to Fergus' banquet table. Esirt refuses to accept any food or drink, so Fergus plops him into his goblet, where Esirt floats around and almost drowns. They make amends, though, and at the end of three days, Esirt goes home along with Fergus' poet Aedh. Although Aedh is the king's dwarf, he still seems a giant to the Lupra people. Now Iubdan and Bebo set off. They want to visit the palace and try the porridge (which Esirt has mentioned) before dawn, so no one will see them. But they can't reach the top of the cauldron. Iubdan has to stand on his horse, finally gets over the edge, only to fall into the porridge and be trapped. Much drama ensues, with husband and wife wailing and singing poetically to each other, until morning comes and people find them. They're taken to Fergus and remain his prisoners for a full year, until finally the Lupra-folk send an army to find them and offer a ransom. But Fergus will accept none of their offers, until Iubhdan gives him his greatest treasure in return for his freedom. This is a pair of shoes which allow a man to walk freely underwater. However, once again, Fergus swims in Lockrury and seals his own fate. This story is recorded around 1517 - a century before the first existing copy of Tom Thumb in 1621, where Tom falls into a pudding and later makes his way to the court of King Arthur. In a later, expanded version around 1700, Tom twice goes to Fairyland and twice returns. The first time, he announces his arrival at court by plummeting into a bowl of frumenty - a dish of boiled, cracked wheat. Basically, porridge. (The second time, he has an encounter with a chamber pot, but let's not talk about that.) In my opinion, there are two unique elements that typically characterize Thumbling tales. The story of Iubhdan and Bebo has both. One is the focus on a character's incredibly small size. The other is the swallow cycle. In the swallow cycle, the character is swallowed by animals and gets out - often multiple times. Tom Thumb travels through a cow's digestive system; is gulped up a giant and spit out; is eaten by a fish and escapes when the fish is caught and cut open. In the Brothers Grimm, there are two Thumbling tales; the heroes are swallowed by cows, foxes and wolves. In one case, the tiny boy yells and complains from inside the cow's belly while it's being milked. In Japan, an oni tries to eat Issun-Boshi, only for the tiny samurai to come out fighting. As you go through Thumbling stories from different cultures, you'll find heroes again and again who are swallowed by cattle, lions, or other animals, and manage to get out one way or another. It's not unlike the Biblical tale of Jonah and the whale. Why exactly does this appeal to humans across so many countries and so much time? “The Catalan Versions of AaTh 700: a Metaphor of Childbirth," an article by Carme Oriole, suggests that the swallow cycle represents pregnancy and childbirth, particularly the way a young child would see it. (A toddler might hear "The baby is in Mommy's tummy" and think Mommy had eaten the baby.) This is particularly apt because most (but not all) thumbling stories begin with the hero's unusual conception and birth. Sometimes the conception is caused by the mother eating a fruit or seed. But it's not just swallowing, it's immersion. Tom Thumb is immersed in a pudding and must break his way out. Similarly, the Grimms' Daumerling is cooked into a sausage. For the Italian Cecino, immersion means falling into a puddle - and death by drowning. For Tommeliten or Tume in Norwegian tales, falling into a bowl of buttered porridge also means death by drowning. Carme Oriole may be right. For the Japanese Mamesuke and the Norse Doll i' the Grass, immersion means falling into a bathtub or a river - and then rebirth. They become human-sized and begin life with their new spouse. In the expanded Tom Thumb, Tom nearly dies, and symbolically is reborn. He returns to the human world each time while being immersed in liquid (like porridge) and reemerging. In most cases the immersion scene is meant as comedy. I don't think the storytellers put much thought into ideas of rebirth. Just "The little man is SO tiny, he falls into some soup and thinks he's drowning!" And the story of Fergus mac Leti manages to fit in two immersions - one in liquor, one in porridge. Although Iubdan and Bebo are little-known today, some writers have suggested that their story inspired Gulliver's Travels, and the scenes in Lilliput and Brobdingnag. (For instance, in the land of the giants, Gulliver is dropped into a bowl of cream and nearly drowns.) I think it's possible they influenced Tom Thumb as well. Resources

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed