|

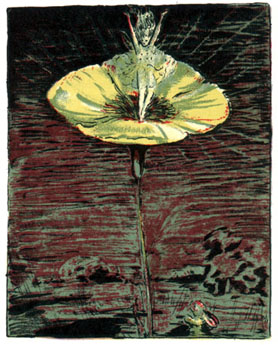

In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen published his fairytale “Tommelise,” or Thumbelina. A childless woman seeks help from a witch and receives a barleycorn. When planted, it grows into "a big, beautiful flower that looked just like a tulip" with "beautiful red and yellow petals." When it opens: "It was a tulip, sure enough, but in the middle of it, on a little green cushion, sat a tiny girl."

In "Thumbelina," Andersen took loose inspiration from older thumbling tales, but the heroine's birth from a flower is unusual. Some thumblings are created from a bean or other small object, but most often he or she is apparently born in the normal way, through pregnancy. Why did Andersen choose to write Thumbelina born from a flower - and what is the tulip's significance? Flower Fairies There's a widespread motif of fairies living in flowers. Andersen would have been well-aware of this trope. Thumbelina later encounters flower-angels (blomstens engels). They are evidently not quite the same species (winged and clear like glass, and dwelling in white flowers), but Thumbelina is happy enough to settle down with them. Another Andersen story, "The Rose Elf" (1839) also deals with tiny flower-dwelling spirits. The tiny flower fairy became popular around 1600. Shakespeare was an important influence; A Midsummer Night's Dream elves creep into acorn-cups to hide, and The Tempest's Ariel sings of lying inside a cowslip bell. In the anonymous play The Maid's Metamorphosis, a fairy sings of "leaping upon flowers' toppes". In the 1621 prose version of Tom Thumb, Tom falls asleep "upon the toppe of a Red Rose new blowne." In the 1627 poem Nymphidia, Queen Mab finds a "fair cowslip-flower" is a "fitting bower." What about older versions of the flower fairy? Greek mythology included dryads and other nature spirits, including the anthousai, or flower nymphs. Before Shakespeare, fairies in legends were generally child-sized at smallest - there are exceptions, such as the portunes of Gervase of Tilbury. Fairies, witches and other spirits were often said to ride in eggshells or crawl through keyholes. Fairies were held to live in nature and dance in "fairy circles" made of mushrooms or grass, or were encountered beneath trees. I'm also reminded of a 6th-century story recorded by Pope Gregory the Great, where a woman eats a lettuce which turns out to contain a demon. The demon complains, "I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." Superstitions held that demons might take up residence inside food if it wasn't properly blessed or protected with charms. Cowslips and foxgloves, already mentioned, were old fairy flowers. Cowslips are also known as fairy cups (Friend, Flower Lore), and foxgloves are fairy caps or as menyg ellyllon (goblin gloves). But these suggest very different scales. Flowers are hats and cups in language, but houses in literature. Katharine Briggs argued that Shakespeare did not originate the tiny flower fairy, but was inspired by contemporary tradition - however, there's not much evidence for this. Diane Purkiss took the exact opposite point of view, deeming it "questionable whether Shakespeare knew anything about fairies from oral sources at all," but I think this is an unnecessary leap. In more of a middle ground, Farah Karim-Cooper suggested that Shakespeare actually rescued fairies. In contemporary culture, they were being demonized, grouped with devils and witches and sorcery. Shakespeare made them benevolent but also tiny, therefore harmless and acceptable. In 1827, Blackwood's Magazine talked about Shakespeare's fairies and how they would "lodge in flower-cups, a hare-bell being a palace, a primrose a hall, an anemone a hut." I do not recall seeing these specific examples in Shakespeare, but this was now the popular perception. In the first 1828 edition of The Fairy Mythology, Thomas Keightley also talked about "the bells of flowers" as fairy habitations. "Oberon's Henchman; or the Legend of the Three Sisters," by M. G. Lewis (1803) describes fairies "Close hid in heather bells". In the poem “Song of the Fairies,” by Thomas Miller (1832), the fairies "sleep . . . in bright heath bells blue, From whence the bees their treasure drew," and then just in case we missed it, their "homes are hid in bells of flowers." Later in the same volume, a fairy named Violet "in a blue bell slept." Hartley Coleridge wrote of "Fays That sweetly nestle in the foxglove bells” (Poems, 1833) and Henry Gardner Adams had "The Elves that sleep in the Cowslip’s bell" (Flowers, 1844). The wood anemone was another fairy flower; at night the blossoms curled over like a tent, and "This was supposed to be the work of the fairies, who nestled inside the tent, and carefully pulled the curtains around them." (The Everyday Book of Natural History, 1866) This implies the existence of another explanatory legend. In a paper presented at a meeting of the New Jersey State Horticultural Society - yes - and published in 1881, the writer reminisced "I remember how I enjoyed the imaginary exploits of the little fairies that had their homes in these flowers. I had always thought it a pretty conceit to make the fairies live in flowers, but never thought how near the truth it is" . . . And then comes a leap to microorganisms. "A flower is a little universe with millions of inhabitants." Children's literature at the time was focused on edifying, providing morals, and providing scientific education. Fairy stories were considered a natural interest for children, and so they were often used to dress up school lessons, particularly on the natural world. They were a perfect way to launch into a lesson on insects or the world that could be found through a microscope. What about tulips specifically? David Lester Richardson's Flowers and Flower-Gardens (1855) mentions that "The Tulip is not endeared to us by many poetical associations." On the other hand, writing a century later, Katharine Briggs believed that the tulip was "a fairy flower according to folk tradition" and that it was a bad omen to cut or sell them. Taking a step back: in European thought, after the crash of the Dutch "tulip mania" in the 1630s, tulips generally became symbols of gaudiness and tastelessness, particularly in superficial female beauty - for instance, Abraham Cowley in 1656 writing "Thou Tulip, who thy stock in paint dost waste, Neither for Physick good, nor Smell, nor Taste." (Rees). As time passed, this faded into the background, but was not forgotten. David Lester Richardson wrote that tulips had remained extravagantly expensive, even in England, as late as 1836. There are a couple of 18th-century examples of tulip fairies. Thomas Tickell's poem "Kensington Garden" (1722) speaks of the fairies resembling a "moving Tulip-bed" and taking shelter in "a lofty Tulip's ample shade." In 1794, Thomas Blake's poem "Europe: A Prophecy" described a fairy seated "on a streak'd Tulip," singing of the pleasures of life. Intriguingly, in the same decade as Thumbelina, an early English folklorist named Anna Eliza Bray collected a story which also featured fairies within tulips. She recorded it in 1832 and published it in 1836, in A Description of the Part of Devonshire Bordering on the Tamar and the Tavy. The story follows an elderly gardener who discovers that the pixies have begun using her tulilps as cradles for her babies. She eventually dies. Her heirs rip up the flowerbed to plant parsley, but find that none of their vegetables will grow there. Meanwhile, the gardener's grave always mysteriously blooms with flowers. Bray does not give a specific source, other than to speak briefly of gathering the tales from village gossips and storytellers, with the assistance of her servant Mary Colling. Bray's pixie story was retold in fairytale collections and books of plant folklore. When she published a children's book, A Peep at the Pixies (1854), most of her focus in the introduction was on pixies’ small size relative to children; they could "creep through key-holes, and get into the bells of flowers." By the 20th century, the tulip as fairy flower was set. James Barrie wrote in The Little White Bird (1920) that white tulips are "fairy-cradles" (158), and Fifty Fairy Flower Legends by Caroline Silver June (1924), reveals that “Fairy cradles, fairy cradles, Are the Tulips red and white." Folklore In fact, fairies were not the only denizens of plants in legend. Birth from plants is very common in fairytales. English children were told that babies might be found in parsley beds, while in Germany, infants were more likely to be found among the cabbages or inside a hollow tree. (Curiosities of Indo-European Tradition and Folklore) In a French version, baby boys were found inside cabbages, baby girls inside roses. (e.g. Revue de Belgique, 1892, p. 227) Gooseberry bushes were also a likely spot. In Hindu culture and mythology, saying someone was born from a lotus was a way to indicate their purity. In Japanese stories, baby Momotaro is found inside a peach, and Princess Kaguya inside a bamboo. The Indian tale "Princess Aubergine" has a girl born from an eggplant. In the Kathāsaritsāgara (Ocean of the Streams of Stories), an 11th-century collection of Indian legends, Vinayavati is a heavenly maiden (divyā-kanyakā) who is born from the fruit of a jambu flower after a goddess in bee-form sheds a tear on it. In the Italian tale of "The Myrtle", from the Pentamerone (1634-1636), a woman gives birth to a sprig of myrtle. A fairy (fata) emerges from the plant each night, and a prince falls in love with her. However, the heroine is apparently of human scale, although she inhabits a plant not unlike a genie in a lamp. Later folklorist Italo Calvino collected more variants: "Rosemary" and "Apple Girl." The woman or fairy hidden within a luscious fruit appears in tale types such as "The Three Citrons." With the first known example of this story in The Pentamerone, there are probably as many variants of this story as there are types of fruit. In a close fairytale neighbor, a mother eats a flower to become pregnant - see the Norwegian "Tatterhood," the Danish "King Lindworm," and "Svend Tomling." "Tom Thumb" is usually cited as an influence on Thumbelina; in this story, a childless woman consults Merlin for help. Merlin prophesies her child's fate, she undergoes a very brief pregnancy, and then gives birth to a child one thumb tall. However, the two stories have little in common; the Thumbling tale type is widespread, and Andersen may have been inspired by other examples. The most likely candidate is "Svend Tomling," a chapbook written by Hans Holck and published in 1776. My translation is very choppy, but I think the gist is that a childless woman consults a witch. The witch causes two flowers to grow and instructs the woman to eat them. The woman then gives birth to Svend, one thumb high and already fully dressed and carrying a sword (beating out Tom Thumb, who has to wait several seconds for his wardrobe). I don't know for sure if Andersen knew this story, which hasn't achieved quite the same ubiquity as Tom Thumb. However, the fact that it was from his own country, and the similarities in Svend Tomling's and Tommelise's births, make a relationship seem likely. E. T. A. Hoffmann Fairytales weren't Andersen's only inspiration. One of his major influences was the fantasy/horror author E. T. A. Hoffmann (creator of The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, among other things). In Hoffmann’s “Princess Brambilla” (1820), a fairytale-esque subplot has the magician Hermod tasked with finding a new ruler for the kingdom. He causes a lotus to grow, and within its petals sleeps the baby Princess Mystilis. The person-inside-flower motif recurs throughout the story. Mystilis is later placed in the lotus to break a curse that has fallen on her, and emerges the second time as a giantess. Hermod himself is frequently seen seated inside a golden tulip. “Master Flea” (1822) has similar imagery. A scholar, studying a "beautiful lilac and yellow tulip," notices a speck inside the calyx. Under a magnifying glass, this speck turns out to be Princess Gamaheh, missing daughter of the Flower Queen, now microscopic and fast asleep in the pollen. Conclusion Andersen created his own thumbling tale inspired by folktales like that of Svend Tomling. However, he wove in plenty of elements in his own way - such as talking animals, or a girl born from a tulip. His work, including both "Thumbelina" and "The Rose-elf," shows the contemporary interest in fairies who lived inside flowers. Andersen's fairies in particular are most like personifications of plants. In the past, tulips had gained a bad reputation, becoming symbols of shallow frippery. However, by the time Andersen wrote, the disastrous tulip fad had had time to fade into history a little more. Instead, tulips started to be mentioned occasionally with fairies. In the 1800s, one author might have noted tales of tulip fairies as rare. However, a century later, Katharine Briggs could categorize it as a fairy flower. What changed? The most important thing may have been new associations for the tulip's shape; it was grouped in with other flowers that resembled bells or cups. I was startled when I went looking for examples of flower fairies - I occasionally found descriptions of them resting on top of the flowers, like Tom Thumb. However, more often than anything, I found the word "bell." Heather-bells, foxglove-bells, cowslip-bells, bluebells, bell-shaped flowers. In 1832, Thomas Miller's flower-fairy poem used the word bell three separate times. With fairies increasingly shrunken around Shakespeare's time, flowers that would have once been cups or hats were instead envisioned as houses or hiding places for fairies. The shape does suggest that something could be tucked inside, and lends itself to an air of mystery. Storytellers, including Andersen, focused on the idea of the hidden observer. Mary Botham Howitt wrote in 1852 "We could ourselves almost adopt the legend, and turning the leaves aside expect to meet the glance of tiny eyes." (George MacDonald used similar images, although with a more sinister slant, in his 1858 book Phantastes.) However, although Thumbelina's birth is still tied to the idea of flower fairies, it has more in common with tales of heroes born from plants. It is also strikingly reminiscent of E. T. A. Hoffmann's short stories; Hoffmann wrote twice of tiny princesses discovered inside flowers. In his work, tulips were not just gaudy or overly expensive, but had esoteric and mystical associations. His characters may be Thumbelina's clearest literary ancestors. Further Reading

Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

1 Comment

David L

9/21/2022 09:52:27 pm

I enjoyed reading these. I'm intrigued by the idea of ordinary items becoming these heavy obstacles or something similar. I liked the descriptions of hiding in cups or traveling through keyholes. The demon in the Lettuce is kind of hilarious.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed