|

Santa Claus isn't the only Christmas character who brings gifts. There's a wide number of different gift-bringers in cultures across the world, and a significant portion of them are ladies.

As far as I can find out, the first mentions of a Mrs. Claus go back to the mid-18th century. In the 1849 short story The Christmas Legend by James Rees a couple disguises themselves as "old Santa Claus and his wife." Then in 1851, in The Yale Literary Magazine, one author remarked that Santa "we should think, had Mrs. Santa Claus to help him." From there, the floodgates opened. Mrs. Claus appeared all over the place in short stories and poems, helping Santa Claus with his work. Some of her other names are Mother Christmas (English), Weihnachtsfrau, Nicolaaswijf (German), Joulumuori, Kerstwrouvtje, Kerstomaatje (Finnish), Bayan Noel (Turkish), or La Mère Noël (French). She never really got a name beyond "Santa's wife" in any of these languages - although in a March 1881 issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, we learn that among Dutch immigrants, St. NIcholas was "sometimes accompanied by his good natured vrouw, Molly Grietje." I have yet to find other textual support for this tradition, and this may not be a factual account of Dutch settlers. In other countries, St. Nicholas was occasionally accompanied by a female counterpart, like the Niglofrau (Nicholas wife) in Upper Austria and the Nikoloweibl in Bavaria. (The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas). In Tirol, there was the Klasa (a feminine variant of Klaus), a well-dressed woman who went in St. Nicholas's processions and distributed gifts from her basket. This was recorded in 1875 in Tagespost Graz. A Friesian nursery rhyme, published in Dutch in 1892, implied the existence of a whole Santa family, with Sintele Zij as the wife. But female gift-bringers of Christmas go back further. In some cases, a female saint appeared in place of Saint Nicholas. One of the most famous was Saint Lucy, whose feast day falls on December 13. In Sweden, there were Lucia processions where she led a troop of children dressed in white, including the stjärngossar or star boys. In the Czechlands, on December 4 - the eve of St. Barbara's Day - women would dress as the Barborky, or Barbaras, in white dresses with veiled faces. They carried baskets of fruit and sweets for the good children, and brooms to threaten bad children. (Czech Traditions and Folklore) (Prague City Line) In some Czech families that immigrated to America, Matíčka or the Blessed Mother would leave treats in children's shoes on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception (December 8). (Christmas in Texas) In a lot of Christian countries, people cut out the middleman and had Baby Jesus bring gifts. However, somehow this got turned around. The German Christkind became America's Kris Kringle, alias of Santa Claus - and in Germany, became a beautiful young girl like Lucia, dressed in gold with a crown on her head. The same thing happened to the Wienechts-Chindli in Switzerland and the Kinken Jes in Sweden. There was also the Wends' veiled Dźěćetko (Little Child) or Bože dźěćo (God’s Child). In other countries, the gift-bringer was an elderly crone like the Befana (Italy), Babushka (Russia), or la Vieja Belén (Dominican Republic). Searching for the Child Jesus, she gives gifts to the children she meets along the way. These Christian characters replaced older figures from older winter festivals. For instance, the Christian martyr Lucy stepped into the shoes of an older figure, the terrifying Lussi. These gift-bringers varied from beautiful, shining young women to monstrous hags. They often made their visits between Christmas and the feast of Epiphany. Perchta, Frau Holle, Hulda, Frau Gode, Frau Lutz, Bertha, Butzenbercht, or Eisenberta (Iron Berta) were some of the many names used for a Germanic goddess figure. Traveling with her assistants, she would bless the people who welcomed her into their homes in the twelve days between Christmas and the feast of Epiphany. She passed judgement on those whose work didn't measure up. According to the Thesaurus pauperum (1486), between Christmas and Epiphany, people left out food and drink at night for a woman named Lady Abundia, Domine Habundie, or Satia. Dame Abonde was apparently still around in the 19th century as a French gift-bringer of New Year, according to Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (1898). Names like Frau Faste and Quatemberca referred to the Ember Days. In some cases, the Perchta character was a hideous monster well-known for her one goose foot and her long beak-like nose - earning her the Austrian name Schnabelpercht or Beak Perchta. Martin Luther referenced "Dame Hulda with the snout." She was also known as the Spinnsteubenfrau, or Spinning Room Lady. In Franche-Comte, Tante Arie was a gift-bringer but also a frightening figure with iron teeth and goose feet. The chauchevielle (also a name for a bogey or a nightmare) and the trotte-vielle were terrifying figures active around the holly-jolliest of seasons. In Iceland, Gryla was a troll who ate bad children and in modern times gained an association with Christmas. In the 19th century, Jacob Brown wrote of his childhood in Maryland and the Christmas visitor known as Kriskinkle, Beltznickle or the Xmas woman. They were disguised and "generally wore a female garb - hence the name Christmas woman." (Brown's Miscellaneous Writings) On the softer side, there were beautiful White Lady types. La Dame de Noel showed up in Alsace. Anjanas, in Cantabria, were fairies of the mountain who would bring gifts on January 6 every four years (Manuel Llano, Mitos y leyendas de Cantabria). So before the beautiful Marys and Lucias, and before the old crones like La Befana, there were already lovely ladies and hideous hags going back to much older myths. These myths surrounded goddesses and demons who were celebrated around the winter solstice. Some of these names, like Bertha and Lucy, have names which intriguingly mean bright or light. St. Lucy, as already mentioned, has "star boys" for companions. In some areas of Poland, the gift bringer was not St. Nicholas, but the Gwiazdor (star man) and sometimes along with him, the Gwiazdka (star woman) or Piękna Pani (beautiful lady). (Star symbolism and Christmas gift-bringers from Polish folklore) Was this related to a celebration of the sun's return and the days growing longer after the winter solstice? More characters have been created during modern times. Mother Goody, Aunt Nancy or Mother New Year brings gifts for New Year’s in Canada. Snegurochka (Snow Girl) is the young female helper of Ded Moroz (Father Frost) in Russia. (Babica Zima, or Old Woman Winter, may also have been proposed as a gift-bringing figure.) In a funny twist, during World War II, women sometimes took up the whiskers and played Santa Claus. "Kristine Kringle! Sarah St. Nicholas! Susie Santa Claus!" one scandalized columnist called them. (Smithsonian) One wonders what that writer would have thought of the older tradition of otherworldly women who came at midwinter with gifts and punishments. Leaving out cookie and milk for Santa probably has its origins in the same tradition where people left out offerings for Lady Abundia.

0 Comments

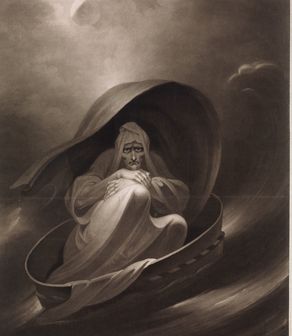

There's a lot of overlap between witches and fairies in older folklore, and the idea of a witch's voyage in an unusual vessel was a common one. According to A Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584), witches like to "saile in an egge shell, a cockle or muscle shell, through and under the tempestuous seas."

All throughout Europe ran the superstition that people should never leave eggshells unbroken. This is mentioned as early as the writings of Pliny the Elder: "There is no one, too, who does not dread being spell-bound by means of evil imprecations; and hence the practice, after eating eggs or snails, of immediately breaking the shells, or piercing them with the spoons." This suggests sympathetic magic, the possibility that someone might use something connected to you to curse you. In 1658, Sir Thomas Browne said that this custom was to prevent witches who might "draw or prick their names therein, and veneficiously mischief their persons." There were many superstitions of eggs being unlucky. Breaking eggshells over a child would deter witchcraft. Strings of blown eggshells were unlucky when hung inside a house. (Signs, Omens and Superstitions, 1918) Any egg taken aboard a ship would cause contrary winds, and some fishermen would not even call them by name, but referred to them as "roundabouts." The relevant thing here is the superstition that eggshells were witches' boats. This was all throughout Europe. Eggshells had to be crushed or poked full of holes, or otherwise either witches or fairies would set to sea in them and wreck ships. Along the same lines, a witch named Mother Gabley drowned sailors "by the boiling or rather labouring of certayn Eggs in a payle full of colde water." This could have been sympathetic magic, "raising a storm at sea by simulating one in a pail." (Folklore vol. 13, pg. 431). Another suggestion put forth in an issue of Notes and Queries was that "witches could use them, if whole, as boats in which to cross running streams." This could connect to the tradition that evil entities like vampires cannot cross running water. Eggshells were also for fairies, as I mentioned in a previous post. In the 1621 chapbook "The History of Tom Thumb," Tom brags that he can "saile in an egge-shel." According to Lady Wilde's Superstitions of Ireland (1887), "egg-shells are favourite retreats of the fairies, therefore the judicious eater should always break the shell after use, to prevent the fairy sprite from taking up his lodgment therein." In the Netherlands, it was said that when eggshells floated on the water, the alven or elves were riding in them. (Thorpe, Northern Mythology vol. 3. 1852.) In Russia, the smallest rusalki do the same thing (Songs of the Russian People.) Apparently these eggshell boats weren't confined to watery voyages, but could cross land too. In 1673, a teenaged girl named Anne Armstrong gave testimony accusing several women of witchcraft. She described one of them arriving at coven meetings "rideing upon wooden dishes and egg-shells, both in the rideinge house and in the close adjoyninge." (Publications of the Surtees Society, vol. 42) Back to Discoverie of Witchcraft - witches weren't just supposed to use eggshells, but cockleshells and sieves. In Cambrian Superstitions by William Howells (1831), a young man sees witches sailing across the river Tivy in cockle shells. A cockleshell has associations with the ocean but is also similar to an eggshell. On the other hand, it's also a word for a small, flimsy boat or for unsteadiness in general. In ancient Greece, "putting to sail in a sieve" was an idiom for undertaking an impossibly risky enterprise. In the comedy "Peace," by the Greek playwright Aristophenes (421 BC), it is said that Simonedes has "grown so old and sordid, he'd put to sea upon a sieve for money." The implication is that he has more greed than sense. In England, however, sailing in a sieve had implications of black magic. In "Newes from Scotland: Declaring the damnable Life of Doctor Fian" (1591), two hundred witches plotting to attack and drown the king "went by sea, each one in a riddle or sieve, and went in the same very substantially with flaggons of wine, making merry and drinking by the way." Macbeth also mentions this tradition. So: going to sea in a sieve was a saying for a risky undertaking. A cockleshell was a small, flimsy boat. Altogether, beings who ride in eggshells or sieves might seem tiny, foolish, or laughable. However, some people seem to have actually followed the superstition that witches or fairies setting to sea in eggshells was a genuine danger. But then, as a character remarks in The Round Table Club (1873), "What could witches not make a voyage in?" Witches and fairies (there's that overlap again) were also commonly said to ride on straw, bulrushes, ragwort, thorn, cabbage stalks, fern roots, rushes, and other types of grass. These unusual steeds would carry them through the air at great speeds - a tradition that's survived in modern depictions of witches on flying broomsticks. Ragwort in particular was called the "fairy horse" in Ireland. De Universo, a work by the 13th-century French bishop William of Auvergne, mentions magicians who believed that demons could create magical steeds from reeds or canes. In Discoverie of Witchcraft (again), the fairies "steal hempen stalks from the fields where they grow, to convert them into horses." Isobel Gowdie, on trial for witchcraft in 1662, said that when people saw bits of cornstraw flying above the road "in a whirlwind," it was actually witches traveling. She may have been inspired by the lightness of straw and the way chaff flew in the wind. (Goodare, J. Scottish Witches and Witch-Hunters). Today witches are often depicted riding on broomsticks. The broom was connected to wind, and therefore an appropriate tool for witches who controlled winds and storms. In Germany, people burned an old broom when they wanted wind, and sailors fighting a "contrary wind" would throw an old broom at another ship to make the wind change direction. (Hardwick, Traditions, Superstitions, and Folk-Lore, 1872, p. 117). And here we are back at the idea of sailors and storms at sea! |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed