|

This review contains spoilers - marked towards the end.

I recently reviewed Thornhedge by T. Kingfisher, which combined the Sleeping Beauty story with legends of changelings. Not long after reading that one, I picked up a very different changeling tale in Unseelie by Ivelisse Housman (2023). The story picks up with Iselia ("Seelie"), a changeling adopted by humans and raised as sisters with her human counterpart Isolde. The two girls live on the road, working as pickpockets after a disaster with Seelie's uncontrollable magic forced them to flee their home. (Where Kingfisher's Toadling is an adult caretaker to her changeling counterpart thanks to time shenanigans, Seelie and Isolde are equals, twins. Their relationship is loving but tumultuous.) Then they stumble upon another two thieves mid-heist, and Seelie winds up with a curse imprinted on her skin, taking the form of a magical compass pointing the way to a long-lost treasure. The groups reluctantly team up to find the treasure, even as Seelie realizes that she'll have to face her dreaded magic and learn to control it. This is Housman's debut novel and it's a decent read, although it feels a little clumsy or muddy at times. The romance takes a while to get going but eventually won me over, and I kind of liked that approach. It is the first in a duology, and ends in an unresolved cliffhanger. However, I was very intrigued by Housman's take on changelings. Housman's novel is woven from two modern ideas surrounding changelings: a recently-created short story that has arguably achieved folktale status, and the theory that changelings were inspired by children with autism. Housman, who is autistic, wrote Seelie inspired by her own experience: "I think a lot of autistic people grow up feeling like we’re from another world, and the idea of putting a positive spin on that feeling within a magical world like the ones I grew up reading was irresistible" (Kirichanskaya, 2023). The changeling as twin is a growing trope, which has done a lot of its growing within Internet culture. (The name 'changeling' can apply to either a stolen human child or its fairy replacement, but in this post I will mainly use it to refer to the fae child.) Thornhedge feels more indicative of the older changeling tales, where faeries are dangerous and changelings are monsters; the story is told from the perspective of the stolen human child. In folktales, changelings might look like babies or disabled children, but many weren't babies at all. They could be pieces of wood, or adult fairies. The reveal of the changeling's true nature often emphasizes its extreme old age. In one Cornish tale, a changeling named Tredrill posing as an infant turns out to have a wife and children of his own (Bottrell, Traditions and Hearthside Stories, pp. 201-202). In a parallel story from Iceland, a changeling in the shape of a four-year-old boy is startled into admitting that he's really a bearded old man and "the father of eighteen elves." In one Danish folktale, "How to Distinguish a Changeling," a father wakes up just in time to stop a changeling swap, but finds himself holding two babies with no way to tell which is his. The family ends up putting the babies through an extremely dangerous test by exposing them to a wild stallion, causing the fairy parent to take back her child (Thorpe, Northern Mythology, vol ii, pp. 175-176). However, moving into the 20th century, more authors started to write stories that treated changelings as children rather than monsters. The first instance I can find of a story where a human family decided to raise both their own child and the changeling is the short original fairy tale "The fishwife and the changeling" by Winifred Finlay (Folk Tales from Moor and Mountain, 1969). Here, the fishwife makes a bargain with the faerie mother—give back her child, and she'll willingly care for and nurse the faerie baby, no trickery needed. The faerie child grows up to consider the humans his true family. Other sympathetic portrayals of changelings became popular. The Moorchild by Eloise Jarvis McGraw (1996) was an influential children's book told from the perspective of a changeling who grows up feeling like an outsider. Holly Black's Tithe (2002) has a teenaged girl discover that she is a changeling. Later in the series, she rescues her human counterpart (still a young child thanks to her time in fairyland), taking the roles of older and younger sisters. In Delia Sherman's Changeling (2006), the human child raised in a fairy realm must work together with her changeling counterpart who's more accustomed to mundane human life, with both returning to their adopted homes at the end. In An Artificial Night by Seanan McGuire (2010), the main character accepts her changeling double as her sister (although the swap takes place when the characters are adults). But the idea of the changeling and human child raised together as twins feels more specific. After Finlay's story, the next "adopted changeling twin" story that I know of appears in The Darkest Part of the Forest (2015) by Holly Black (again). In a key part of the backstory, a woman turns the faeries' games back on them. She burns the faerie baby with a poker to summon the faeries to return her son. However, then she announces with righteous fury that she will also keep the faerie baby: “You can’t have him,” said Carter’s mother, passing her own baby to her sister and picking up iron filings and red berries and salt, protection against the faerie woman’s magic. “If you were willing to trade him away, even for an hour, then you don’t deserve him. I’ll keep them both to raise as my own..." Not long afterwards and along the same lines - but with different logic behind it - in March 2017, the Tumblr blog magic-and-moonlit-wings posted a very short story titled "Rescue and Adoption," published on Tumblr (March 2017). The story starts in medias res inside a fairy mound. The fairies present a woman with two perfectly identical babies and give her a choice. One is her own, and the other is the changeling she's been raising. She startles them with her declaration that both are her children, one biological and one adopted, and returns home with both babies. The premise is reminiscent of the Danish folktale, with a family left trying to identify their true child after fairy trickery, but the message is diametrically opposed. The woman rejects the fairies' game and lovingly accepts both children. "Rescue and Adoption" went somewhat viral. Many people wrote their own spins with the original author's blessing. An abbreviated version was posted as a writing prompt on Reddit (March 2022) and on Tumblr (April 2022), leading to even more reimaginings. (Here is one example, an untitled story by Tumblr user Dycefic, which begins with a childless woman being told to plant a pear tree in a manner reminiscent of "Thumbelina" or "Tatterhood".) The number of retellings and adaptations make this a modern folktale in its own right. There is an echo of the same sentiment in the middle-grade book Changeling by William Ritter (2019). Here, as in the Danish folktale, a parent interrupts the changeling switch just in time, but is left with two babies and no way to tell which is which. However, although other people in the village are fearful of the changeling and suggest dangerous tests, she decides to care for both as her own. But Housman's book is even more directly inspired by the "Rescue and Adoption" tale. As previously mentioned, it is also built on the theory that changeling tales were inspired by children with autism, which was circulating on Tumblr around the same time. See, for instance, this group discussion circa 2016. The short story "here's a story about changelings" (posted August 2019) is a realistic tale about autistic children growing up in a world where the only name for them is "changelings." Out of works already mentioned here, Delia Sherman's Changeling and dycefic's take on the "Rescue and Adoption" prompt both nod to this theory by featuring changeling children with autistic traits. There may be some truth to the autism theory, and there are some compelling parallels. In traditional stories, the changeling is detected when a healthy, beautiful baby undergoes an apparent change in personality and a regression in hitting typical milestones - similar to some autism diagnoses. But I would argue that the legend came from a mix of many different factors: disabilities, failure to thrive, postpartum depression, and/or chronic illness. See the tragic case of Bridget Cleary: when she fell ill in 1895, her husband murdered her, claiming that he was trying to retrieve his real wife. In 1643, a folk healer and accused witch named Margaret Dickson was unable to heal a sickly child. She then told the mother to throw it onto the fire because "the bairne was not hirs." The mother opted not to take Dickson's advice, and the child apparently recovered (Scottish Fairy Belief: A History, pg. 97). Martin Luther encountered a disabled child that he believed was a changeling and child of the devil. As far as I'm concerned, the changeling myth is the darkest fairy tale, because at least some people believed in it and acted on it. In some cases, it may have been a cautionary tale warning people not to leave children unattended. But in others, it was an excuse for societally-sanctioned neglect and murder. (Major spoilers from this point on) So far, Unseelie falls in line with many other takes on the "Rescue and Adoption" tale. However, a deft twist towards the end casts the whole story—and modern changeling tropes in general—in a different light. The mother in Unseelie is absent, but the story of her long-ago rescue of her children underlies the entire plot. Much like the mother in Kingfisher's Thornhedge, she is courageous and determined and loving—but maybe that's not enough. Housman stated in an interview, "I approached this story with the intention to take the changeling myth, turn it upside down, and reclaim it—all through the lens of a fantasy world... All that to say, changelings in this world are autistic people, and vice versa" (Creadan, 2023). Towards the end of Unseelie, it is revealed that Seelie was the original human child, and her neurotypical sister Isolde was the duplicate created by the fairies. (Housman also includes the more modern idea that the changeling swap can leave the mortal child with magical abilities of their own.) Seelie's mother assumed that she was a changeling, and thus went to the fairies and demanded her "original" daughter back. The malicious fairies were happy to play along, producing Isolde. Seelie's mother still behaved admirably by accepting both children and thwarting the fairies' cruel game, but is it enough to make up for her inherent rejection of a daughter who didn't match her expectations? We'll see where the second book in the duology takes things. Housman's followup, Unending, is expected to be published in 2025. Bibliography

0 Comments

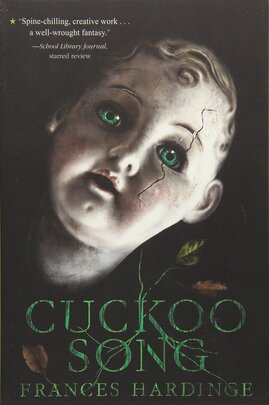

Cuckoo Song begins with a girl waking up in bed after a mysterious injury. Her memories are foggy, her own family seems unfamiliar . . . and she feels voraciously hungry, no matter how much she eats.

This children's book is set in the 1920s not long after the first World War, and centers around Triss, a young girl from a well-to-do but deeply dysfunctional family. Ever since the death of her older brother in the war, the family has been unhealthily divided and deeply miserable. And now there is something wrong with Triss. Ready for spoilers? This is a changeling story. Dark psychological horror. It's eerie, bizarre, and nightmarish, with some really beautiful prose. Many of the characters, not just Pen, are not what they seem at first. The slowly evolving friendship between Triss and her little sister Pen, for instance, was one of my favorite parts. Another character that will stay in my head for a long time is a kindly tailor, whose determination to save a lost child brings out one of the most unnerving threats in the book. The fairies in this book are bonkers. They are creepy dark fairies, but they are also modern in a way, intertwining with the technology and aesthetics of the 1920s. You can use a telephone to call the otherworld. In one scene, a child is sucked into a silent black-and-white film. Scissors actively seek to kill anything fairylike. This is the kind of book where a girl unhinges her jaw to swallow a china doll whole. It's exactly as weird as it sounds, and it works. Overall, the mood is very dark, but there was one scene towards the end of the book, in a crowded restaurant, that legitimately made me laugh out loud. I particularly love that the changeling in the book is not a fairy child replacement. I have read so many changeling fantasies where the hero turns out to be a long-lost fairy prince or princess. This changeling story is inspired by tales where the replacement is a carved piece of wood, meant to pose as a corpse and fool people into believing their loved one is dead. What would it be like to learn that you're not who you believe you are? And not even an enchanted Chosen One - nothing but a decoy? That's one plot idea I've been wishing I could read, and here it's played to its fullest extent. Personally, I am adding this to my list of favorite books. I actually stumbled on the Wikipedia summary to begin with and was kind of baffled, but when I sat down to read the book, I finished it in one sitting and thoroughly enjoyed it. If you're looking for a dark and utterly original changeling tale, featuring a sweet friendship between siblings, check this one out. You can read an interview with author Frances Hardinge on her inspirations here. Last time, I looked at stories where fairies steal humans. The human dwells in Fairyland as a lover, an adopted child, a pet, or a servant. Sometimes the fairies leave a doppelganger in their place, so that no one will miss them. But there's another side to the coin: tales where humans steal fairies.

It's hard to say why fairies take humans. Storytellers give any number of reasons, or none at all. But it's usually pretty clear why humans take fairies.

Lust In the tale of the selkie, swan wife, or fairy bride, a man sees an otherworldly being take off her magic cloak or garment. He steals it and holds it hostage so that she will stay with him as his bride. That's the most classic tale of a human stealing a fairy. Invariably, she gets her coat back and vanishes. Sometimes rather than steal a coat, the man makes a deal with the otherworld, and there are conditions on their marriage. Again, he inevitably breaks the bargain. For instance, in some Welsh variants, the bargain may be that he never strike his fairy wife. He accidentally taps her one day without meaning to, and she vanishes forever. Human women might win fairy men, too. In many versions of Tam Lin, the titular character is a human stolen away by the Fairy Queen. In at least one version, however, there's no mention of him ever being human. He introduces himself as "a fairy, lyth and limb." Greed for Gold In another widespread tale, a man catches a leprechaun or fairy and tries to threaten him into giving over his store of treasure. The fairy shows him where it's buried, under a certain tree or plant. The man marks the tree, perhaps with a scarf or marking, and runs home to fetch a shovel - but when he returns, the fairy is gone, and every tree bears an identical mark. In the Cornish tale of "A Fairy Caught" or "Skillywidden," a human farmer captures a fairy child and treats him rather like a pet, while hoping to get fairy gold from him. For even on their own, without magical gold, fairies are valuable. An 1851 news article from Ireland contains a mention of a supposed mermaid sighting. The reaction is telling: "It is a pity the crew could not catch her, as, in that case, the exhibition of such prodigy would make the fortune of all the fishermen on the shores." Greed for Power Hidden stores of gold are one thing; hostage potential and fairy magic are another. In the German tale of "The Wonderful Plough," a farmer manages to capture a fairy being in an iron pot. After a long captivity, he forces the fairy to give him a special plow that can be drawn easily through the fields. This reminds one also of witches with familiar spirits and the concept of sorcerers summoning demonic familiars. An old English manuscript has a spell "To Call a Fairy," laying out the instructions and incantations for summoning a being called Elaby Gathen and binding it to one's will. Fairies are powerful servants - like Prospero's manservant Ariel in Shakespeare's play The Tempest. This theme continues into modern literary tales. In "Bubblan," a 1907 tale by Swedish author Helena Nyblom, translated into English as "The Bubbly Boy," a family captures a merchild by accident. The father, a fisherman, holds him hostage to force the merfolk to send him good catches of fish. Kindness The story of the Green Children of Woolpit is often regarded as a fairy story. Dating from 12th/13th-century accounts, two children with strange green skin, speaking an unknown language, showed up in the village of Woolpit. Both were taken in and baptized and eventually lost their green coloring. The boy died not long after baptism, but the girl adjusted to her new life, learned English, and eventually confided that she was from an underground land where everyone had green skin. This is a case where the fairy children are treated as kindly as their discoverers know how. The humans try to make the fairy children acclimate to human life. Sometimes a human couple who long for a child wind up with a supernatural one instead. In Undine, a novella published in 1811, a fisherman and his wife adopt a water-sprite child and lovingly raise her as their own. This is a more benevolent relationship on the humans' part - but it's possibly implied that the water fairies killed their biological child. Their daughter, playing by the water, seemed "attracted by something very beautiful in the water" and sprang in, only to be lost. The very same day, a "beautiful little girl" - the titular Undine - arrives at the home of the grieving parents. Another tale where humans willingly take in a merchild is the Chilean "Pincoya's Daughter," in Brenda Hughes' Folk Tales from Chile. And there's Ruth Tongue's "The Sea-Morgan's Baby" (presented as traditional) in which humans raise a mermaid foundling. This seems particularly frequent with water beings. Maybe it's Undine's influence. Colman Grey, an English tale, is a lot like Skillywiddens, but the human family finds a starving fairy child and takes him in out of pity. Benevolent enough, but the storyteller mentions that the family was aware there was a chance for good fortune if they pleased the fairies. The South African psikwembu or shikwembu are ancestral gods whose behavior and stature is similar to that of European fairies. In one story recorded by Henri A. Junod, a woman finds what she believes is a child lost in the woods, and carries him home. When she arrives, he cannot be removed from her back, and people realize his true nature. The priests do a ritual and the god disappears. However, although her actions were well-meaning, the woman dies as a result of the encounter. Amusements, Pets or Curiosity In the Suffolk tale of "Brother Mike," a farmer catches fairies in the act of disturbing his wheat stores and manages to capture one in his hat. Like the farmer in "Skillywidden," he takes the fairy home "for his children." In this case, however, the fairy pines away and dies in captivity. In the cases of the fairy in "Brother Mike" and Skillywidden, the small size of the fairy is emphasized; in one, the fairy is captured in a hat, in the other, carried inside a "furze cuff" (furze cutters wore leather gloves to protect their wrists from furze needles). These tiny fairies, like dolls or kittens, are seen as appropriate to the child's sphere. They are dehumanized and treated like playthings or pets. By Accident In some tales, a human picks up a fairy completely by accident. A fisherman may draw up a mermaid in his nets, for example. However, some humans choose to keep the fairy captive. Others immediately release them, such as in the German story of Krachöhrle, where a man realizes that he has not caught a badger but an elf, and quickly releases it from his trap. The same thing happens in an English tale from Lancashire. Unclear Reasons Some stories don't give enough details to prove what's going through the human kidnapper's head. A legend collected by W. H. D. Longstaffe in County Durham in England: a correspondent's grandmother had seen fairies wash their clothes in the River Tees, and one day encountered "a miniature girl, dressed in green, and with brilliant red eyes." The woman took the strange little child home and fed it. However, it is difficult to tell whether the woman was well-meaning or simply nosy and intrusive. The tiny fairy girl seemed "composed" when found, and when taken indoors, cried so much that the woman was "obliged" to put her back where she found her. The woman's willingness to return the fairy child makes it seem that she had good intentions in the end, but the fact that she knew exactly where to return her to, and the fact that she kept the fairy's stone chair, make me suspicious. In Teutonic Mythology vol. 2, Jacob Grimm collected the tale of "The Water-Smith" or "The Smith in Darmssen Lake." In the middle of a certain lake is a strange blacksmith who sits in or on the water and works on whatever ploughs or tools are brought to him. (A fairy who works in iron? Intriguing.) One farmer, however, snatches the smith's son - a child who is completely hairy or rough - and raises him as his own. As an adult, the waterkind (water child) or ruwwen ("Shag" or "Roughy") leaves his human family in a story reminiscent of "The Young Giant" tale type, and returns to his watery home. The story feels oddly incomplete. It's not clear why the farmer kidnaps the Roughy; the action is sudden, impulsive and bizarrely cruel. After he does so, the blacksmith vanishes and never does work again. What did the farmer want? Curiosity, perhaps? Or maybe he wanted to use the child to start a rival to the blacksmith's business, or keep the smith's abilities for himself, or maybe he even believed he was helping the fairy child. Conclusion The list of why humans abduct fairies is shorter and less esoteric than why fairies abduct humans. It's easy to imagine what a human's reaction would be to finding a fairy in their power. There's also the possibility that a human can pick up a fairy by accident or mistake in a completely random encounter; I don't know that I've come across any stories where a fairy takes a human by accident. What fascinates me is how much overlap there is.

In the end, we assign our own thoughts and rationales to the otherworld. We imagine for fairies the same motivations which we hold. Further Reading

The story appears all over the world. Fairies take humans into their world, leaving doppelgangers behind. Sometimes fairies leave their own child, or a grown fairy, or an elderly decrepit one - or just a piece of wood carved to look like the stolen person.

But explanations are harder to obtain. Scattered stories give a variety of causes for this odd fairy behavior. It seems there are quite a few uses that fairies have for humans. Here are thirteen possible explanations I've collected. 1. No reason given/malice/caprice A majority of changeling tales give no reason. For instance, in "Rumpelstiltskin," the fairylike being is eager to obtain a human infant, but we never learn why. Fairies just like to take people, along with anything, really. Westropp's Study of Folklore on the Coasts of Connacht, Ireland explains that fairies “carried off children and robbed milk and butter. The sprites could exercise malignant power on infants especially before baptism, stealing the handsome ones and replacing them by puny withered changelings . . . Women who die in childbirth are believed to have been carried off to fairyland." In a story recorded by John Rhys in Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, a woman banishes a "crimbil" and regains her son - "But when she asked him where he had been so long, he had no account in the world to give but that he had been listening to pleasant music. He was very thin and worn in appearance when he was restored." This indicates that the fairies did not even care much for the human they had taken. 2. The human trespassed on fairy domain A human who goes into fairy territory is always at risk. Don't step into fairy circles or eat their food! In the tales of Sir Orfeo and Thomas the Rhymer, a human attracts the attention of fairy royalty when they sleep in the shade of a particular tree. In "Child Rowland," Burd Ellen falls into the elf-king's power because she runs around the church widdershins. Similarly, a human may be taken as revenge for a broken taboo or for spite. In a Swedish tale, a servant-girl takes home a cow belonging to the fairies. The angry trolls promise that they will have revenge, and on the girl's wedding day they snatch her away (Lindow p. 96). 3. Fairies want a beautiful child instead of their own ugly baby "People fear that the misshapen dwarfs who live beneath the earth, and who would like nothing more than to have beautiful, well-formed human children, will steal newborns, leaving their own malformed children, called changelings, in their place." (J. D. H. Temme, Folk Legends from Altmark) According to Thomas Keightley, fairies look for human infants with the intention of offloading any fairy children "which they foresee likely to be feeble in mind, in body, in beauty, or other gifts." According to Icelandic Legends (page liii) "the finest children are the most sought for, and the most hideous oldling is put in their place." (So fairies get some cute babies and also find a cheap retirement home for Grandpa. Two birds, one stone!) Fairies may have a special preference for blondes in particular. Katharine Briggs (An Encyclopedia of Fairies, p. 195) says that golden-haired children are the most in demand from fairies, citing the Welsh tale of Eilian of Garth Dorwen, where the abducted woman is explicitly mentioned as blonde. Sir John Rhys, in Celtic Folklore Vol. 2 (pp. 667-668), mentioned twice that fairies like to steal blond babies above all others. Fairy babies, in contrast, are "swarthy," "sallow," and "aged-looking." In addition to blond hair, fairies apparently had a preference for male children. Adult abductees were men or women, in fact possibly usually women, but the typical changeling story features a baby boy. According to some sources, the practice of dressing boys in girls’ frocks until age ten or eleven was intended to deceive fairies who might steal away a boy and replace him with a changeling (Irish Folk Ways). Lady Jane Francesca Elgee Wilde in Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland gives an interesting variation. An old hag switches a human child for a hairy, ugly, grinning creature. However, as the human parents bewail their misfortune, a young woman in a red handkerchief enters and begins to laugh. She's the fairy parent of the changeling, and was just as upset by the switch! The other fairies, preferring the "fine child" of the humans, stole hers to replace it. But she proclaims, "I would rather have my own, ugly as he is, than any mortal child in the world" - and instructs the human parents on how to steal back their offspring. Lady Wilde also cited an interesting idea that physical beauty might not last forever. She described a tradition that although fairies will kidnap human brides, "after seven years, when the girls grow old and ugly, they send them back to their kindred, giving them, however, as compensation, a knowledge of herbs and philters and secret spells, but which they can kill or cure." 4. Fairies want breeding stock or human lovers Perhaps there is such emphasis on beautiful human children because the fairies want to ensure good genetics in their future generations. In a German tale, a "maniken" informs the stolen child's mother that "her son would someday become the king of the underground people. From time to time they had to exchange one of their king's children for a human child so that earthly beauty would not entirely die out among them." (Bartsch, Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Meklenburg, 1879, p. 46) Lady Wilde also said that "handsome children" are taken by the Sidhe and "wedded to fairy mates when they grow up." The fairies definitely seemed to look at some humans as potential mates and lovers. In many Rumpelstiltskin-type tales, instead of trying to steal a baby, the fairylike helper wants the woman to become his wife and live with him underground, in Fairyland or Hell. Examples are "Mistress Beautiful," "Doubleturk," "Zirkzirk," "Purzinigele," and "Duffy and the Devil," as well as many others. In medieval ballads, this is the most common reason for humans to go away with the fairies - see Thomas the Rhymer, Sir Lanval, or Sir Guingamuer. In another family of tales, a woman is stolen away by a fairy and bears him children. There's "Agnete and the Merman," "Little Kerstin and the Mountain King," "Jomfruen og Dværgekongen," and "Hind Etin." In stories like that of Eilian, a human midwife visits the fairies only to recognize the mother in childbed as a long-lost member of her own village. 5. Fairies raise human children out of love In some tales, the fairies are kind foster families to the humans they adopt. For instance, in "A Midsummer Night’s Dream," Titania has a changeling boy as a squire, and Oberon wants him as one of his knights. Titania lavishes affection on the child (“crowns him with flowers, and makes him all her joy”), and claims she is raising him out of love for his mother, a dear friend of hers who died in childbirth. This is, of course, Shakespeare's spin on tradition. Diane Purkiss, in Troublesome Things: A history of Fairies and Fairy Stories, draws a connection to Greek nymphs. The exposure of newborns - leaving unwanted children in the wilderness to die - was not uncommon in Ancient Greece. Good news though - myths said that nymphs would raise these children. Nymphs could be motherly figures, taking care of the infant god Zeus, for instance. In the Homeric hymn to Aphrodite, a woman plans to abandon her illegitimate baby, comforting herself with the idea that mountain nymphs will take care of him. However, Purkiss says, modern Greek nymphs have developed in the popular mind to become malicious baby-stealers. In the Cornish tale of Betty Stogs, recorded by Robert Hunt, a lazy and slovenly woman neglects her baby and it vanishes with the fairies. On this occasion, however, the pixies simply wash it, care for it, and lovingly return it wrapped in soft moss and flowers. In this case there is no changeling; the baby's absence is brief, and serves only to knock some sense into the neglectful parents. In many tales, mistreating the fairy child is the best way to get the human back. In Norwegian variants, though, it’s common for the angry fairy parent to rebuke the human, implying that they have been kind and loving foster parents in contrast.

Selma Lagerlof wrote a story called "The Changeling" where the troll parents treat the stolen child exactly as the human parents treat the changeling. The human mother goes against tradition by refusing to mistreat the changeling, which ends up saving her own child's life. If stolen and recovered humans did not waste away after their return, they often came back with wondrous knowledge and gifts from the fairies. Thomas the Rhymer retained prophetic powers. In the Scottish tale of "The Smith and the Fairies," a stolen boy returns with an uncanny gift for sword-forging. 6. Fairies want to make humans like themselves. Sometimes the stolen child becomes one of the fairies, transformed either in whole or in part. In John Fletcher's play The Faithful Shepherdess (c. 1608), we hear of: A virtuous well, about whose flowery banks The nimble-footed Fairies dance their rounds, By the pale moon-shine, dipping oftentimes Their stolen children, so to make them free From dying flesh, and dull mortality. According to The Borderer's Table Book (1846), changelings were treated quite well: "the elves were... so liberal as to tend it with great kindness, and, by degrees, they brought it to partake almost of their own qualities . . . . it lived and was treated as one of themselves." Similarly, in Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm's Deutsche Sagen, it's mentioned that some of the "nixies" of the Saal River were once human - "mortals who, as children, had been taken away by nixies." Ralph of Coggeshall recorded the tale of a strange spirit called Malekin which haunted a certain house around the late 12th century. Malekin was invisible, but sounded like a toddler and once appeared as a small child in a white tunic. He (or she?) claimed to have once been a mortal child, born in Lavenham. When his mother left him in a field while she worked harvesting, he was taken away. Malekin had existed in spirit form for seven years, and in another seven years would be restored to a human state. 7. Fairies punish neglectful parents Fairies are known to pinch and abuse slovenly humans and aid those who are hard-working; it seems they take an interest in our proper conduct. Betty Stogs and her husband are careless parents who don't spend time caring for their baby or keeping it clean. In more widespread stories, the baby is taken while the mother goes to fetch wood, bind sheaves, or other household tasks. This is shown in the tale of Malekin. n a tale collected by the Grimms, a nobleman forces one of his tenants to help bind sheaves even though she has a six-week-old baby still nursing. She lays the child on the ground while she works, but to his shock the nobleman observes an "Earth-woman" steal and replace the baby. They get the baby back, but in the moral, the nobleman "resolved to never again force a woman who had recently given birth to work." This is a cautionary tale about leaving young infants unattended. Neglectful parents are shown the need to change their ways, but also – as D. L. Ashliman points out – such superstitions served some benefits. They insisted that women must have a rest period after childbirth. New mothers should be recovering and caring for their newborns, not forced back into strenuous physical labor. Parents were warned by changeling superstitions to keep a close watch on their children. Mother and newborn had to be closely guarded. Talismans, such as a piece of the father’s clothing kept nearby, or scissors hung over the cradle, were used to protect the child. If these rituals were neglected, fairies might strike at any moment. The parents are responsible for keeping their offspring out of the fairies’ hands. In this case, a changeling swap implied neglect. Walter Scott mentioned a story where the mother, recovering and alone, is unable to stop her child’s abduction on her own. Here the blame is placed on the nurse, a lower-class woman, who had been drinking and fell asleep rather than guarding her charges. In another widespread class of tales, the parent carelessly wishes for the child to be taken away. For instance, in the 13th-century tale of "The Daughter of Peter de Cabinam," a man angrily wishes that his crying daughter would be taken away by demons. His unthinking words come true, and she's taken to the demons' realm beneath a lake to toil as a servant. The father manages to regain her seven years later, but she is sickly and mute. Although they're called demons, her captors' behavior and home is very fairylike. In “Polednice,” a poem by Karel Jaromir Erben based on the Slavic folklore, a woman threatens her noisy child that she will give him to the polednice (a spirit personifying sunstroke) if he doesn't obey. To her horror, the spirit actually arrives at her summons and the story ends tragically. 8. Fairies require human servants This is what happened to Peter de Cabinam's daughter. Lady Wilde in Ancient Legends of Ireland mentions that young men are taken by the fairies to become "bond-slaves." In "The Fairy Dwelling on Selena Moor" (Bottrell 1873), the fairies who capture a woman "wanted a tidy girl who knew how to bake and brew, one that would keep their habitation decent, nurse the changed-children, that wern’t so strongly made as they used to be, for want of more beef and good malt liquor, so they said." In a Swedish tale, a girl taken by trolls is forced not only to labor for them but to don a cap of invisibility and steal food from human farms for them. (Lindow no. 32) 9. Fairies require human protection for their own children This may be more of a literary invention. However, Robert Hunt's Popular Romances of the West of England gives the story of "The Piskies' Changeling," in which a fairy child is found abandoned, and we hear that piskies sometimes to this with "infants of their race for whom they sought human protection; and it would have been an awful circumstance if such a one were not received by the individual so visited." Here is an entirely different dynamic! Anna Eliza Bray, in The borders of the Tamar and the Tavy, mentions that a woman who was kind to her changeling "so pleased the pixy mother that some time after she returned the stolen child, who was ever after very lucky." 10. Fairies just really like milk The days after birth were a dangerous time. Either women or newborns might be swept away, and a common theme was that fairies wanted humans to serve as wet nurses. According to Thomas Keightley, "Lying-in-women and 'unchristened bairns' they regard as lawful prize. The former they employ as wet-nurses, the latter they of course rear up as their own." In the ballad "The Queen of Elfland's Nourice," a mortal woman is taken from her own newborn to nurse the Queen of Elfland's child, and told she will be allowed to go home afterwards. In a Hessian legend, a dwarf-woman brings back the real baby, but refuses to hand it over until the human mother has nursed the changeling with "ennobling human milk." (Grimm, Deutsch Mythology, via Keightley) In Asturian folklore, xanas may sneak their babies into human families in order to get them milk. (Del folklore asturiano, pp. 36-38). Although some stories have it that xana mothers did not have enough milk, others state that xanas don't even have breasts (Baragaño, Mitología y brujería en Asturias p. 22). In a more sinister turn, in "The Red-Haired Tailor of Rannoch and the Fairy," a rapacious adult fairy poses as a screaming human baby solely to get milk. (James MacDougall, Folk Tales and Fairy Lore in Gaelic and English) 11. Fairies want baptism for their own kids Usually baptism is supposed to ward off changelings, and this is why an unbaptized child is in especial danger. Once the baby's baptized, the fairies cannot touch them. However, in Robert Buchanan’s poem “The Changeling,” a mother asrai explicitly wants her child to have a human soul and a chance at Heaven. And a few rare folktales make it seem like there's a basis for this. In an Asturian tale, a woman notices that her child has been switched. She runs to the cave where the "Injana" (similar to anjana or xana) lives, and demands her baby back. The Injana responds, — Tráelo acá, mala mujer: no te lo di para que me lo criaras, dítelo para que me lo bautizaras. “Bring it here, evil woman: I didn't give it to you to raise it for me, I gave it to you to baptize it for me.” In one Swedish tale, a troll changeling is about to be baptized. You might expect him to be displeased, but it seems the trolls had planned for exactly this; he cries out gleefully that he is "off to the church to become a Christian" (Lindow pg. 92). Lindow notes that the changeling is "delighted" at the possibility of being baptized. In other stories, Christian salvation is normally a gift denied to fairykind - see my blog post The Salvation of Mermaids. (Other versions of this tale don't always include baptism. The English "Changeling of Brea Vean" is being carried to a healing well, and in a story from the Grimms, the changeling is being taken on a pilgrimage at the end of which he will be weighed. Both are religious rituals meant to encourage a sickly child to thrive.) 12. Fairies need human midwives Much like wet-nurses, fairies like to use humans as midwives. However, these midwives are typically allowed to go straight home once their task is completed. Even for this brief time, some may be replaced with a changeling; Biddy Mannion returns home from aiding a fairy birth, only to cross paths with the doppelganger who has been keeping her place. "What a gomal your husband is that didn't know the difference between you and me," the fake Biddy comments. 13. Fairies need replacement tithes to hell? The story goes that every seven years or so, fairies must offer a living sacrifice to Hell. Not wanting to give up fairy babies, they grab up human babies instead to offer those as a kind of draft dodging. The hell-tithe has been given as a fact of fairylore by Katharine Briggs, Lady Wilde, and many other prominent folklorists running through possible reasons for changelings. However, this story isn't reflected by tradition. For exaxmple, Walter Gregor, in Notes on the Folk-Lore of the North-East of Scotland, gives the hell-tithe as an explanation for changelings . . . but also directly quotes Tam Lin (pp. 60-62). This leaves it unclear whether he has actually heard folktales which feature a fairy hell-tithe, or whether he is tying in the story of Tam Lin on his own. Tam Lin is one of only three tales which mention a fairy tithe to hell, making this a rare concept. These tales do indicate that humans visiting Fairyland are in danger of being selected as a living sacrifice. However, they are not in danger because they’re human – it seems to just be a danger of proximity, or the fact that they are “fat and full of flesh” or healthy specimens. In addition, none of these tales feature any exchange of changelings. I would dismiss this explanation as a later theory based on unconnected tale types. The changeling as symbolism for death/illness/disability There's a lot of overlap between fairies and the dead. Remember one of the first books quoted in this post: "Women who die in childbirth are believed to have been carried off to fairyland." All of these changeling myths are associated with a vulnerable time in the lives of mothers and infants. There are two types of changeling tales. In one, a sickly or disabled child is actually a demon which must be caught in the act. The mentally or physically handicapped child is an impostor; the parents' real, healthy and attractive child was stolen. This myth dehumanized handicapped or sick people and was a way to excuse infanticide - not just in stories, but in real life - see Young, 2013. In the other, a deceased or missing loved one (typically a wife) turns out to actually be alive. Their "corpse" was a false image. They may yet be rescued if their families just manage to complete the right ritual. Both types of changeling tales speak of grief and denial. This was people searching for a reason why something bad had happened - or perhaps a scapegoat. Sometimes they came up with a reason why otherworldly forces did what they did. However, more often there was no point. In the Malleus Maleficarum, (1487), fairy activity is attributed to demons. It calls the supposed cases of changelings - simply and brutally - "another terrible thing which God permits to happen to men." A search for a "reason" belongs more to later scholarly efforts. For people who believed in changelings, questioning it bore no purpose; questions might even attract the wrath of otherworldly forces. The issue was not "Why did this happen?" but "What do we do now?" SOURCES

The classic resolution to the story of the changeling: A fairy doppelganger has posed as a human baby and successfully pulled the wool over its human hosts' eyes. However, someone (typically the mother) realizes what's happened. To trick the changeling, she uses empty eggshells as milk pans, stewpots, or brewing cauldrons. The fake infant is so surprised that he suddenly begins to speak. Sometimes he is startled, sometimes amused. "I have never seen the like of that before" is the most common exclamation, as he unthinkingly reveals his great age. Then, in a flash, all is set right and the real baby is returned.

This story is widespread throughout Europe. But why? What is the significance of eggshells? Bear in mind that people actually believed in changelings well into the 20th century. Other remedies for a changeling were things like putting it on a hot shovel, leaving it out in the elements overnight, or threatening the suspected elf with torture. In an infamous 1895 case, a man named Michael Cleary killed his sickly wife Bridget, insisting that she was a fairy and his real wife had been taken away. He was found guilty of manslaughter. There were other such cases that made it to the news and incited outrage, and probably far more that were never publicized. As suggested by D. L. Ashliman, changeling beliefs may have been a more palatable excuse to kill a disabled relative who was seen as burdensome. The eggshells are a gentler method. Rather than threatening the child in brutal ways which remind of real practices, this story is more palatable. The parents need not threaten anything wearing the face of an innocent baby. The changeling is ancient and manipulative, but it is still possible to trick it. It reveals itself and (usually near-instantly) the problem is solved. Even if beating it or leaving it on a trash heap overnight is still required, the parents now know for sure that they are torturing a monster and not their own flesh and blood. There are plenty of superstitions regarding eggs, and the shells were often associated with witches and fairies. Pliny in the 1st century makes a reference to breaking eggshells, apparently to protect against magical harassment. At least by 1584, in Reginald Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft, there was an elaborate explanation: witches and fairies used eggshells as boats or houses. In one case, a witch was accused of sympathetic magic using eggshells in a cauldron to simulate ships at sea, then wrecking real ships by stirring the cauldron. In this tradition, the shells are associated with sympathetic magic. They are a simple tool easily subverted by dark forces and used for mischief. In Waldron’s Description of the Isle of Man, a mermaid says that humans "are so very ignorant, as to throw away the water they boil their eggs in." Campbell's Superstitions of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland (1900) tells us that "water in which eggs have been boiled or washed should not be used for washing the hands or face." This is highly unlucky. Also, it was an idiom for someone who'd done something dumb to say "I believe egg-water was put over me." Campbell mentions a man who asked a mermaid "what virtue or evil there was in egg-water . . . She said, 'If I tell you that, you will have a tale to tell.'" One possible explanation: according to Legends & Superstitions of the County of Durham (1886), washing in egg-water causes warts. On the other hand, the accused witch Elspeth Reoch, in 1616, said that fairies had instructed her to roast an egg and use its sweat to wash her hands and rub her eyes, which would give her any knowledge she wished. I wonder if there is some connection from the egg to birth and babyhood. Most changeling traditions focus on newborns, the days after birth, the period before christening. The changeling is posing as an infant too young to speak. Eggshells are a symbol of new life, and the fairies have choked off life from the family's home by stealing the newest life there. However, eggshells in changeling tales are also somewhat random. Anything, not just eggs, can be used by humans to bewilder fairies. In an Icelandic tale, a woman binds rods to a spoon to create a long handle, confusing the changeling into exclaiming, "Well! I am old enough, as anybody may guess from my beard, and the father of eighteen elves, but never in all my life, have I seen so long a spoon to so small a pot." Even when the stories do feature eggshells, they may be used in different ways. They may be left in front of the changeling as-is, or used as pots to boil water or cook food. Sir Walter Scott retold a Scottish tale where a fairy changeling spoke up when left alone with twelve eggshells all broken in half. In this case, the bewildered fairy says it has "Seven years old was I before I came to the nurse, and four years have I lived since, and never saw so many milk pans before." In this case, rather than the human parent confusing the fairy by telling them they're making dinner in an eggshell, the fairy itself misidentifies the shells. This points to traditions where fairies live inside eggshells and use them as boats, or where fairies are extremely miniature. In at least one case, fairies seem disturbed and possibly even offended by such behavior. In "The Egg-Shell Dinner," collected by Thomas Crofton Croker, a farm is plagued not by changelings but by mischievous spirits. A wise woman instructs the farmer's wife to boil a tiny amount of pudding in an eggshell, ostensibly as a meal for six hungry farmworkers. The fairy-poltergeists announce, "We have lived long in this world; we were born just after the earth was made, but before the acorn was planted, and yet we never saw a harvest-dinner prepared in an egg-shell. Something must be wrong in this house, and we will no longer stop under its roof." Sometimes the eggshells themselves are boiled in water. In Thomas Crofton Croker’s version of the “Brewery of Eggshells,” the mother is told to “get a dozen new-laid eggs, break them, and keep the shells, but throw away the rest; when that is done, put the shells in the pot of boiling water.” The fairy has reversed the way things should be – a cunning, articulate, ancient being behaves like a baby too young to speak. So the human family performs another reversal. In a nonsensical and wasteful display, the mother throws away food and cooks garbage. Once the changeling is gone, things may return to their normal state. In nearly all cases, there are mentions of how the changeling does nothing but eat ravenously - screaming for milk or eating the family out of house and home. Therefore, in some versions, the eggshell theme makes it clear that there is now an end to the changeling's "free ride," which prompts them to call it quits. In Ireland: Its Scenery, Character, &c, vol. 3, people suggest getting rid of a changeling by this method: "to make egg-broth before it, that is, to boil egg-shells and offer it the water they were boiled in for its dinner, which would make it speak at once." And in a Danish tale, a girl serves a voracious changeling the most inedible pudding possible, containing bones and pighide. He declares, "Well, three times have I seen a young wood by Tis Lake, but never yet did I see such a pudding! The devil himself may stay here now for me!" With that, he's gone. So inedible or unappetizing food drives off the changeling who is just using the family for a free meal. (At the same time, this is tacit permission to starve the troublesome child who isn't thriving.) Also note that whether or not the ritual includes an eggshell, it is still nearly always associated with cooking. This could be a memory of real-life rituals in which "changelings" were treated by being burned. Rather than putting the changeling itself into the fire, the changeling is forced to watch something else being heated in the fireplace. There's an implicit threat. In cases where the Slavic water demon Dziwożona or Boginka sometimes left changelings, human mothers were to take the changeling to a garbage heap, whip it with a rod, and pour water over it using an eggshell, all while calling to the Boginka to "Take yours, return mine!" (Madrej glowie dość dwie slowie, Krzyżanowski, 1960, p. 73) Perhaps this is a confusion of the eggshell story with the idea of torturing a changeling. Similarly, in 1643, accused witch Margaret Dickson had performed healing rituals which suggest she attributed sicknesses to fairy changelings. After her attempt to heal a sick child had no effect, she told its mother to throw it onto the fire because "the bairne was not hirs" and was really a hundred years old. The mother ignored this advice and the child began to recover. In a second case, Dickson advised a man to place meal baked with twelve eggs in front of a fire, and his crippled child on the other side. Then he was to walk around the house, calling the spirits to "give me my daughter againe, and if the bairne mend the bread and egges wald be away, and if not the shells and bread wald be still." Was this an offering - a trade of food for the return of the healthy child? (Scottish Fairy Belief: A History, pg. 97) These stories are rationalizations, excuses. Note that in nearly all of these tales, the changeling isn't just a fairy baby, but an ancient, malicious, cruelly clever being which takes joy in the human parents' agony. Many changeling tales end with the note that even after the ordeal of burning or beating, the rescued child is frail or physically changed. This is explained as the result of its time in Fairyland... but... well... Look at the story with historical cases in mind, and it becomes very dark indeed. I much prefer the modern story "The Changeling" by Selma Lagerlöf, where the mother's tender care for the changeling - and her absolute refusal to torture it - convinces the trolls to return her real son. I also like the Orkney tale of the Rousay Changeling, where a woman recovers her child by tracking down the fairy who took him, and smacking said fairy in the face with a Bible. It should be mentioned that not all suspected changelings were harmed. As mentioned, one of Margaret Dickson's "patients" apparently flat-out refused to follow her advice. In a few stories, we hear that human parents who took care of their fairy fosterlings were blessed with good fortune (as in the tale of the Changeling of Sportnitz). Another Scottish witch, Jonet Andirson, confirmed to a suspicious father that his child was a "sharg bairn," but told him that so long as he had that sick child in his house, he would not want - i.e., if he was good to the fairy child, his family would be taken care of. (The Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, vol. 8, p. 347) Further Reading Every seven years, the fairies must pay a tax to Hell: a living sacrifice. To save themselves, they steal humans as changelings to sacrifice in their place. This folktale has served as the seed for many modern-day faerie fantasy books - Tithe by Holly Black being one example. But the idea of the fairy tithe in actual folklore is rare, rare, rare. Only three stories hint at it. These are a) Thomas the Rhymer, b) the trial of accused witch Alison Pearson, and probably most famously, c) the ballad of Tam Lin. Thomas the Rhymer Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, famously known as the poet/prophet Thomas the Rhymer, lived about 1220-1298. The romance "Thomas of Ercildoune" has been dated as early as the 14th century, and the oldest existing versions of the ballad adaptation "Thomas the Rhymer" go back to 1700-1750. Everyone has different ideas on when they were originally written. And did the ballad come first, or was it the romance? In this story, Thomas the Rhymer is swept away to Elfland by a fairy queen who becomes his lover. But he cannot stay. The queen sends him home lest he be seized by a foul fiend of Hell who takes a tithe from among the people of Fairyland. Thomas returns to our world with skills as a storyteller and prophet. "Thomas of Erceldoune" and "Thomas the Rhymer" are similar to other ballads and poems like "St Patrick's Purgatory" and "The Daemon Lover" in that there are scenes where a mortal, visiting the Otherworld, is able to see Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory from afar. This sets Thomas's Elfland as a spiritual realm akin to both Paradise and Hell, but also clearly separate. Tam Lin Tam Lin is a famous Scottish ballad. The Complaynt of Scotland (1549) features the oldest existing mention of ""the tayl of the Ȝong tamlene and of the bold braband." A dance "thom of lyn" is also mentioned. These may or may not be Tam Lin. The ballad form of Tam Lin appeared in "Kertonha, or, The Fairy Court" (collected by Francis James Child as ballad 39C), dated to 1769. Many other versions have been collected. A young woman, Janet, is in the woods when she encounters a knight named Tam Lin, a man stolen away years ago by the Fairy Queen. Every seven years, on Halloween, the fairies give a tithe to Hell. Tam Lin is likely going to be that tithe. It's up to a now-pregnant Janet to rescue him, which she does in a climactic transformation sequence. Tam Lin bears a resemblance to the ancient Greek myth of the goddess Thetis. A mortal man was chosen to be her husband, but in order to win her, he had to hold onto her while she transformed into all sorts of shapes - just as Janet must do with Tam Lin. In the same way, Tam Lin overlaps with a lot of other stories, including that of Thomas the Rhymer. Alison Pearson Alison Pearson or Alesoun Peirsoun was a woman from Fife, executed for witchcraft in 1588. In her testimony, she described being taken away by fairies and learning mystic arts of healing from them. She claimed that her cousin William Sympson was also part of this, and that he was responsible for warning and rescuing her: "Mr Williame will cum before and tell hir and bid hir keip hir and sane hir, that scho be nocht tane away with thame agane for the teynd of thame gais ewerie 3eir to hell." Or translated: "Mr. William will come before and tell her and bid her keep her and sane her, that she be not taken away with them again, for the teind (tenth) of them go every year to hell." Was Alison inspired by the stories of Thomas the Rhymer and Tam Lin, or by a now-lost tradition that birthed both stories? Tithes Each of these three stories deal with a part of the fairy court going to hell. This is always something which the mortal characters are warned about and must avoid. Tithe, teind, kane, and fee are all words used. Tithe or teind comes from the Old English word for "tenth." A tithe is a tenth of your money or belongings, traditionally given to a church or temple. This is a traditional element in Judaism and Christianity. In this case, the tithe is not paid to a church, but to Hell, and it plays out as a human sacrifice. The religious element implies that the fairies worship the devil. Kane, on the other hand, is a Scots word referring to a vassal or tenant's fee paid to their landlord. It has nothing to do with tenths, and implies that the fairies hold fealty to Satan. From another angle, in almost all versions of Tam Lin, this scene takes place at Halloween. (The exception places it at May Day.) The idea that the fairy court went riding at Halloweentide was very common, showing up in the ballad of Alison Gross, Alexander Montgomerie's Poems, and others. Halloween (All Hallows' Eve) and All Saints' Day are Christian feast which were used to supplant the Gaelic festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-win). This holiday marked the end of harvest and start of winter. Samhain was a time when spirits and fairies or Aos Si moved freely in the human world. People left out food to appease the dead who might visit, and wore disguises to avoid them. Most importantly, In the Irish work Lebor Gabála Érenn, from about the 11th century, Samain was tax time. People were forced to deliver two thirds of their children, wheat and milk as a tax to the Fomorians, otherworldly beings who had taken over the land. Halloween, the time that the fairies go riding, is the time of a harvest tax. Fairies as servants of Hell The tithe or kane to hell puts fairies in the position of either worshippers or tenants of Satan. There's a tradition throughout Europe that fairies are fallen angels (see "Origin of Underground People"). As the story goes, when they were cast out of heaven, they were not quite as evil as the demons, or they did not quite make it all the way to Hell and instead landed on Earth. Katharine Briggs called them "not quite devils and yet subject to Satan." According to Kathleen McGowan in The Ballad of Tam Lin, the Hell-tithe is a Christian invention meant to demonize the fairies. Hell and human sacrifices would be absolutely foreign to the ancient Celtic fairy. To McGowan, ancient fairies are essentially good, not evil. She points to their alternate names of "the good folk" and "good neighbors.” Says McGowan, "evil simply could not and did not exist in the land of fairy." Unfortunately, the name "good folk" cannot be taken at face value. There are many names for fairies - e.g., the Fair Folk, the Gentle Folk, the Seelie (happy, blessed) Court. But taking those names literally would be a major error. They are closer to the ancient equivalent of the Eumenides (Kindly Ones) in the Greek play Orestes, from 5th century BC. The Kindly Ones are really the Erinyes, “Furies,” terrifying and brutal bringers of justice. See also this Scottish rhyme, where a fairy explains its preferred terminology:

Names like "the good folk" or "the kindly ones" are euphemisms for the more ambiguous imp, elf, and fairy. People called fairies good and blessed not to describe them, but to appease them and avoid summoning them!

But there is still a leap from that to tying fairies directly to demons. The language choices and very concept of Hell and Satan are Christian. Christians did demonize English and Scottish fairies, along with all spirit beings from other cultures. A big part of this process happened during the English Reformation. Reformed Christians reinterpreted tradition and folklore to fit a Protestant worldview. According to Darren Oldridge, "By the late sixteenth century, it was well established among reformed Christians that such 'doubtful spirits' were figments encouraged by the Roman [Catholic] Church." Fairies, demons, witches, superstition, illusion, and popery were all wrapped up together. Robin was a euphemistic nickname for the devil and also the name of the famous Robin Goodfellow. Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan (1651) called fairies servants of "Beelzebub, prince of demons." Witch trials featured both Satan and the Fairy Queen, and witches' familiars had names similar to those of folkloric fairies. (See Emma Wilby, "The Witch's Familiar and the Fairy in Early Modern England.") As for changelings, there was plenty of overlap between fairies and demons, with both playing the role of baby-snatchers. (See my blog post "The History of the Cambion.") The death of Alison Pearson and the oldest surviving references to Tam Lin were both in the mid-to-late sixteenth century, putting them right in the middle of this era. The tithe to hell in Alison Pearson consists of a tenth of the fairy population going down to Hell. That would have been a natural conclusion for people of that time. Of course the fairies were going to Hell; where else would they go? "Thomas the Rhymer" predates those stories. Thomas' fairy queen is kind and loving. There are different ways you could interpret her character, but she is at least not all bad. Elfland is explicitly separate from both Heaven and Hell. Still, even at that point, there was the idea of a being from Hell taking away the finest fairy specimens as a fee. Why did this fee need to be paid? Tam Lin as Changeling This is one of the most prevalent explanations today, both for Tam Lin's tithe and for the concept of changelings. It's accounted for from many folklorists and scholars. Lowry Charles Wimberly, writing in 1959, stated blithely that this was standard belief in Scotland. Fairies took changelings in order to offer them to Hell. Fairies be crazy. There are various muddled explanations for the fairy predilection for baby swaps. Some say that they want their own children nursed by human mothers, or that they prefer beautiful human children to their own, or perhaps just out of pure malice and mischief. Tam Lin offers a bloody and memorable answer: so that fairies can dodge the draft. They don't want to sacrifice a fairy child to Hell, so they use a human instead. This tied in with the idea, particularly strong due to the Reformation, that fairies held fealty to Satan. However, I see no evidence for this theory. Tam Lin and Thomas the Rhymer are the only fairy stories that really feature the concept of the hell-tithe. According to Emma Lyle (p. 130), "in the absence of other evidence for the story, it is perhaps more likely that the two narratives are directly related." The relevant stanzas in Thomas of Erceldoune and Tam Lin are similar in language and structure, making it likely that one influenced the other. So what about the changeling theory? Firstly, Tam Lin fears that he'll be chosen as the tithe not because he is human, but because he is one of the most handsome: "fair and full of flesh." Only two versions have him in danger specifically because he's mortal. And in Version C (one of the earliest surviving versions), Tam Lin isn't human at all. He identifies himself as "a fairy, lyth and limb" and tells Janet that "at every seven years end/ We’re a’ dung down to hell." So the entire fairy court is going. The versions are actually very inconsistent on whether just one person will be sacrificed, or if a tenth of the population will go, or whether all the fairies are going. It's also not even clear whether Tam Lin's even on the chopping block. In Child's Version 39A, for example, all we have is his suspicion that he'll be sacrificed, and the Queen of Fairies seems angry not to have lost a potential sacrifice, but to have lost "the bonniest knight in a' my companie." Secondly, there is no fake changeling Tam Lin hanging out in the human world, so far as we know. Still, as evidence, Emma Lyle lists multiple Scottish tales with a similar idea. In this tale type, someone (typically a woman) has been carried away by the fairies, but someone (typically a male relative) may retrieve her from the fairies' march on Halloween if he pulls her from her horse and does not let go. In some versions he's successful, but in others, he falters at the last moment and she is lost forever. Lyle gives ten versions of similar tales, but only one of the examples given explicitly mentions a changeling - cases where a "wife was taken by the fairies, and another woman was left in her place." The wife's death comes suddenly, and then the husband realizes that the woman he buried was a fraud and his real wife has been stolen. Other versions could imply the same thing, when they make references to the wife's supposed death. Another problem is the lack of any mention of Hell, the Devil, tithes, or kanes. The woman in these stories only says that she will be lost forever. In a couple of the examples, after a rescue goes awry, there is the gruesome detail of the walls of the house being covered with blood the next day. In one example, the stolen girl confides that if the rescue fails, the fairies will kill her out of spite. But that's still not a hell-tithe. The changeling-as-hell-tithe is a theory from later researchers, based on three different tale traditions.

So it's an intriguing theory tying together these different stories, but has little evidence. It's just been repeated as common knowledge by different researchers. But what if we look at it through a different lens, laying aside the comparison to changeling tales? Could the hell-tithe be a memory of an older, pre-Christian tradition? The fairy tithe as remnant of pagan sacrifice The website tam-lin.org suggests that Tam Lin is a harvest figure or Sacred King. This trope was codified by James Frazer in The Golden Bough, his study of mythology and anthropology. The theme: a king-consort is chosen every spring. His people celebrate him all year until harvest-time, at which point they ritually sacrifice him. There are many customs of straw effigies being created and burnt at harvest-time. Myths abound where gods of crops, fertility or the sun die and return, like the fields that spring back to life. So perhaps Tam Lin is being sacrificed as part of a harvest ritual that takes place every seven years. The time of year is definitely right. This also ties in with the idea of the Samhain tax to the Fomorians, who demanded human sacrifices as well as food from the harvest. The Fomorians were a supernatural, semi-divine race who came from the sea or from underground. Here's our pre-Christian concept that otherworldly beings demanded human sacrifice around Samhain! Alternately, Fairies: A Guide to the Celtic Fair Folk by Morgan Daimler points to drownings and sacrifices to river deities. According to this theory, "Thomas the Rhymer" takes place near the river Tweed and "Tam Lin" is set off the Ettrick Water, a tributary of the Tweed. Daimler raises the possibility that Tam Lin's sacrifice could be a memory of a regular human sacrifice offered to the Tweed - a small localized tradition, explaining why only these few stories mention the tithe to Hell. This is particularly intriguing because Tam Lin's name could be tied to water. The Gaelic "linn" is a pool, pond, body of water, lake, or sea. This theory is fun but relies on some guesswork and jumps. Alison Pearson, from the more distant Byrehill, Fife, is another issue. Conclusion Although often circulated and popular in modern books, the tithe to Hell was apparently never a widespread belief. Only two tales - which are probably closely related - mention it, and one witch trial. No other stories, changeling tales or otherwise make mention of a tithe to hell. The story we know today has to have picked up a lot of elements after Christianity was established in that area of the world - Satan, Hell, the collusion of fairies and demons. However, it is interesting how far back the separate pieces of Tam Lin go. A human who obtains a supernatural spouse by holding on as they transform into different shapes? Greek myth. Otherworldly beings who demand a human sacrifice at Samhain? Irish myth. A mortal stolen away to the Otherworld, who has to be won back? Pretty much everywhere. Sources and Further Reading

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed