|

There's an interesting motif in folktales surrounding fairies' reaction to Christianity, and their hope for an afterlife. Norwegian folklorist Reidar Thoralf Christiansen categorized these as Type 5050, Fairies' Hope for Christian Salvation. You can find some of these tales at D. L. Ashliman's site. The story can vary widely, but generally - in tales collected from Sweden, Norway, and Ireland - a preacher tells the fairy that they will not receive God's salvation. The inconsolable fairy begins to weep and wail. However, in some versions, the preacher has a change of heart and gives them some hope.

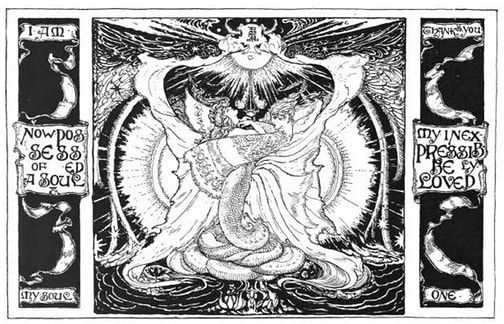

Some fairies try to enter the church via subterfuge, by switching out a human baby for a changeling. In a Swedish tale, the human mother learns the truth on the way to her son's baptism, when the infant boasts to the other fairies, "I am off to the church to become a Christian." The Asturian xanas were known to try the same trick, according to Mitología y brujería en Asturias by Ramón Baragaño (1983). This ties in with ideas of fairies' origins. In some stories, they are the spirits of the dead, particularly unbaptized children. The rusalka in Russian lore are the ghosts of drowned women. In another school of thought, fairies are fallen angels. In the Irish tale "The Blood of Adam," the fairies cannot be redeemed because they are not of the human race for whom Christ died. But in Norway, the story of "The Huldre Minister" goes in the exact opposite direction. A minister seeking to convert the fairies is surprised when one knows the Bible as well as he does. This one claims that the fairies are the descendants of Adam - by his first wife Lilith instead of Eve. Lilith was not involved in humanity's original sin, so they don't need to be redeemed at all. It seems like there's a particular theme of water spirits seeking redemption. The xanas live in rivers, and the fairy-salvation story is told of the Swedish Nack or Nickar, a water spirit. Even when they're not explicitly water fairies, they may appear by a river, as in one Irish story. The idea of water spirits' salvation really takes form in stories of mermaids who lack souls. This theme appeared in the work of Paracelsus, a Swiss alchemist. In his 16th-century work Liber de Nymphis, sylphis, pygmaeis et salamandris et de caeteris spiritibus, he described four types of elemental beings: undines (water), sylphs (air), gnomes (earth) and salamanders (fire). Despite their powers, they lack the eternal soul that humans possess. The only way for them to acquire a soul is to marry a human being. Any children of this union would be born with souls. According to Paracelsus, the most common marriages were of humans to undines - as with Melusine or the nymph bride of Peter von Stauffenberg. There are echoes of folklore here, but he's definitely creating his own mythology. In German, there's a word for marriage between a human and a supernatural being: Mahrtenehe. As pointed out by Claude Lecouteux, Paracelsus turns the Mahrtenehe motif on its head. In traditional lore, the supernatural being often leads the human to a new, eternal existence in another realm. In Roman myth, Cupid makes Psyche a goddess on Olympus, and in medieval legend, Sir Launfal's bride takes him away to Fairyland. Paracelsus, however, has the human guiding the elemental away from its heathen origins, to eternal life in Heaven. Paracelsus' influence continued in works like The Comte de Gabalis (1670). This widely read French novel revolved around a secret society of mystics. They abstained from marriage, hoping to offer their service as husbands to nymphs. It is currently considered a satire of occult philosophy, but was taken seriously through most of its history and inspired the use of Paracelsian elementals in other literature, like the poem The Rape of the Lock. This led to many works where humans fell in love with elemental beings. One example is the ballet "The Sylphide." Another is Friedrich de La Motte's famous 1811 novella, Undine, which concerns a water nymph marrying a human in order to gain a soul. If her husband is ever unfaithful, she will lose her soul again and he will die. It's basically an adaptation of "Peter von Stauffenberg" by way of Paracelsus. These stories about soul-marriage are literary tales. I can't think of any stories from oral folklore that include this theme, except that in the Orkney Islands, the Fin-Folk could retain their youthful beauty only if they married humans. Much like the fairies mentioned earlier, the Fin-Folk had an uneasy relationship with Christianity. They couldn't live where the Gospel was preached, hated the sight of crosses, and a man could escape them by repeating the name of God three times. (Scottish Antiquary, 1891) (Folklore mermaids can vary wildly from cross-fearing murderesses to the churchgoing Mermaid of Zennor.) There are stories like "The Peasant and the Waterman" from Germany and "Lidushka and the Water Demon's Wife" from Bohemia. In these tales, merfolk trap the souls of drowned victims underwater, but a visiting human opens the cages and frees them. Thomas Keightley suggested that this was inspired by older mythology of sea deities who took drowned souls to themselves. Undine's successor was Hans Christian Andersen's Little Mermaid (1836). Andersen didn't like Undine's ending, where the nymph depended on a human being for salvation, and had the Mermaid work her way to Heaven on her own merits. "The Little Mermaid" inspired countless variations of its own, such as Oscar Wilde's "The Fisherman and His Soul" (1891). Robert Buchanan also used the soul theme for the asrai in "The Changeling: A Legend of the Moonlight" (1875). Those last two toy with the inherent themes of the old folktale. "The Changeling" takes a dark, cynical view of humanity; the soulless nature spirits are far more virtuous than humans. "The Fisherman and his Soul," which deals with a human giving up his soul to be with his mermaid lover, celebrates love while raising questions about religion. In these stories, to be soulless is to be in a state of innocence rather than evil. So, to recap: there have always been legends of marriage of humans to gods or other powerful supernatural beings. As Christianity became established, authorities demonized the old pagan gods and spirits. They were recreated as evil beings that feared the church even if they wanted to enter it. Paracelsus put his own spin on the story: these creatures had a shot at redemption by marrying humans, in which case they could earn their own soul. This inspired the tale of Undine, which inspired The Little Mermaid. More recent reactions, if they address this, tend to question established Christian ideas about salvation and the soul. Sources

Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed