|

I’ve written about the history of tiny fairies - how fairies, always portrayed in a range of sizes, have become more likely to be depicted as only a few inches tall. This time, I’d like to look at something along the same lines: narratives explaining how fairies have dwindled over time. I’m not talking about the trope of fairies who change size at will, but the idea that fairies were once big, and are now small, because they shrank.

A major theme in accounts of fairies is that they were once greater than they are now. Fairies have faded or are no longer seen. No matter how far back you go, they’re a thing of the past, always just out of reach. The Canterbury Tales, written 1387-1400, place the deeds of fairies back in “tholde dayes of the king Arthour,” and explain that “now can no man see none elves mo.” In a bit of wordplay, friars have replaced fairies as Christianity crowds out spirit-worship. It’s a short step from this to the idea that the fairies haven’t simply left - they’ve shrunken. Standish O’Grady wrote "undoubtedly, the fairies of mediæval times are the same potent deities [as the Tuatha De Danan], but shorn of their power and reduced in stature.” Yeats also referenced this theory - the gigantic Irish gods “when no longer worshipped and fed with offerings, dwindled away in the popular imagination, and now are only a few spans high." These are later writings, based on the theory that the fairies are direct adaptations of pagan gods. It’s also confusing how we’re meant to take these accounts of shrinking: Are they literal? Metaphorical? Both? Stewart Sanderson responded to this kind of theory - “Personally I cannot take too seriously the confusion of moral or spiritual stature with physical stature.” So, he doubts the claim that people stopped believing in the gods as powerful, so they started envisioning them as pocket-sized. I would agree that’s kind of a stretch. And what about statements like "In Cornwall, the Tommyknockers were thought to be the spirits of Jewish miners from long ago, reduced in stature until they became elf-like" (James 1992). It might indicate a narrative about gradually shrinking Jewish miners, but upon reading further, I haven’t found any explicit mention. Ghosts are simply smaller than their living counterparts in that tradition. However, there are a few stories where the dwindling of the fairies from large to small is clearly literal. Most of these stories are connected to Cornwall. Cornish belief tells that ants, or Muryans, are fairies “in their state of decay from off the earth,” and it is unlucky to kill an ant. (Hunt 1903) In "The Fairy Dwelling on Selena Moor," the fairies are ghosts who waste away over the centuries until they cease to exist. They are also shapechangers, and “those who take animal forms get smaller and smaller with every change, till they are finally lost in the earth as muryans (ants).” (Bottrell 1873) Here, shrinking is a natural part of the fairy life cycle, explaining why these wraiths are so much smaller than their living counterparts. The most recently deceased among their group is closer to average human stature. Evans-Wentz’s collected Cornish pixy-lore mentioned that “Pixies were often supposed to be the souls of the prehistoric dwellers of this country. As such, pixies were supposed to be getting smaller and smaller until, finally, they are to vanish entirely.” The trope appeared in the more ornate, literary tale of "Wisht Wood,” by Charles Lee. Here, the Piskies, or Pobel Vean, shrink or grow in direct relation to how many people believe in them. They were once giants and gods, but when Christian missionaries sprinkled them with holy water, they shrank to the size of dwarves. They continued to progressively shrink as the last traces of pagan faith waned, until they were only a few inches tall. They feared the approaching day when “the muryons send out hunting parties to chase us from wood and more, and the quilkens [frogs] run at us open-mouthed.” (Note the mention of muryons - the piskies are not becoming ants, but they are still mentioned in connection with them.) The piskies beg a priest to tell their stories and encourage just a little belief in them, "that we may not shrink to dust". The narration closes with the idea that the pixies have clung to life, but still continue to dwindle away with modern agnosticism replacing religious censorship. This is very different from the previous examples, where shrinking is a natural part of fairy life. This is an outside condition; their size depends on human belief. I have a feeling that this story is mostly Lee’s creation, but it still has markers of Cornish folklore. So far, I’ve found one other example outside Cornwall. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's 1807 story "Die Neue Melusine" (The New Melusine) is a literary example from Germany. The “Melusine” of the title is from an ancient race of dwarfs, who are progressively shrinking - the reason given is that "everything that has once been great, must become small and decrease.” They intermarry with humans so that they won’t shrink to microscopic size. (Note that ants appear here too, as a dangerous rival nation which may attack the dwarfs.) Conclusion This is merely a beginning to researching this trope and there’s much more work to be done. However, so far there are two trends. First is a later, scholarly theory that the pagan gods shrank into fairies, which is partly metaphorical, and doesn’t necessarily represent folk belief. Second is a Cornish theme that shrinking is part of a fairy’s (or pixy’s, or muryan’s) natural life cycle. These fairies are actually ghosts, ranging from the recently dead to ancient forgotten tribes. Goethe’s “The New Melusine” is interesting, and I wonder if there may be other German sources to be found. If you know of any other examples of shrinking fairies, then leave them in the comments! Sources

1 Comment

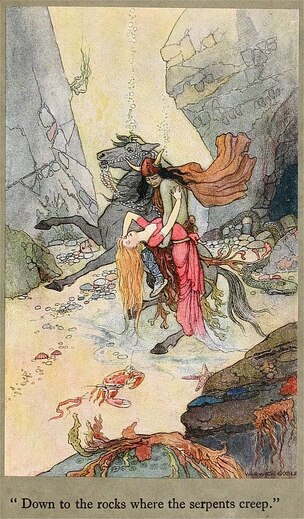

"The Water-Horse of Barra" is a fairytale that's stayed with me since I read it years ago. It is especially striking because it takes one of the cruelest monsters in Scottish legend and turns him into a redeemable hero. The story has been presented as a folktale, but I began to wonder if it was really traditional or not.

The tale appeared in Folk Tales of Moor and Mountain by Winifred Finlay (1969). On Barra, an island off the coast of Scotland, there lived a water-horse or each-uisge - a shapeshifting water spirit, similar to the kelpie. The water-horse went seeking a bride, and captured a young woman by tricking her into placing her hand on his pelt. However, the quick-thinking girl invited him to rest a while, and he took human form in order to sleep. While he slept, she placed a halter around his neck, trapping him in horse form and forcing him to do her bidding. She then kept him to work on her father's farm for a year and a day. However, during that year and a day, he learned love and compassion. Rather than depart for Tìr nan Òg (the Scottish Gaelic form of Tir na nOg, the Irish otherworld), he underwent a ritual to become truly human, losing even the memory of being a water-horse. He and the girl married, and lived happily ever after. Winifred Finlay was an English author who published numerous folklore-inspired novels and collections of folktales. In Moor and Mountain, she gives no sources, leaving it mysterious how she found these stories. This should be an immediate cue to look at them critically. Some of them are familiar. Midside Maggie and Tam Lin are well-known, and "Jeannie and the fairy spinners" is a retelling of the story of Habetrot. However, others are less familiar to me, such as "The Fair Maid and the Snow-white Unicorn" (which, like "Water-Horse," features a girl marrying a handsome man who used to be a magical horse). I have never found an older equivalent of Finlay's water-horse romance, although it has been retold in other collections. It appeared as "The Kelpie and the Girl" in The Celtic Breeze by Heather McNeil (2001) and "The Kelpie Who Fell in Love" in Mayo Folk Tales by Tony Locke (2014). A running theme in Finlay’s books is that the world of fairies and magic has ended, with the modern human world taking its place. In "The Water-horse of Barra," "Saint Columba and the Giants of Staffa," and "The Fishwife and the Changeling," magical creatures must either leave this world forever, or assimilate and become ordinary humans. "The Water-Horse of Barra" bears an especially strong resemblance to "The Fishwife and the Changeling." Both tales follow a traditionally evil entity who is won over by the love of a human woman, and who opts to become mortal and stay with her rather than depart for the Land of Youth. In the second case, the woman is a devoted mother who adopts a fairy changeling and raises him alongside the child he was meant to replace. Although I adore this take on the changeling mythos, it is strikingly different from most folktales, where any compassion towards changelings would be unusual. In a tale recorded in 1866, a parent who accidentally winds up with both babies still resorts to the threat of torture to get rid of the fairy child (Henderson, Notes on the Folklore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders, 153). The idea of a changeling and the original child raised as siblings is fairly new, although it seems to be growing popular in recent fiction - see, for instance, The Darkest Part of the Forest by Holly Black (2015) and The Oddmire: Changeling by William Ritter (2019). Back to the Water-Horse of Barra. This tale features many of the usual kelpie tropes. A person who touches the water-horse will find herself trapped as if glued to his skin. However, if the creature is haltered or bridled, he becomes docile and tame - at least as long as the halter is in place. In other ways, however, it is strikingly atypical. Kelpies are usually totally murderous. Although they are often found pursuing women, it is generally to eat them. There is an older tale about a Water-horse of Barra. However, this tale is very short and takes a gruesome turn. A young woman of Barra encountered a handsome man on a hill. They chatted, and eventually he fell asleep with his head in her lap. However, she noticed water-weeds tangled in his hair, and realized to her horror that he was a water-horse. Thinking quickly, she cut off the part of her skirt that his head was resting on, and slipped away to safety. However, some time later when she was out with friends, he reappeared and dragged her into the lake. All that was ever found of her was part of her lung. This story was told by Anne McIntyre, recorded by Reverend Allan Macdonald of Eriskay, and published by George Henderson in 1911. (Henderson, Survivals in Belief Among the Celts) It is rare for the kelpie to be seen with a softer side. J. F. Campbell gives a one-sentence summary of this story type in Popular Tales of the West Highlands, where he states that the kelpie "falls in love with a lady." The summary ends with her finding sand in his hair and presumably reacting with horror. The phrasing is fairly soft, suggesting that a kelpie could really fall in love, but all of the other kelpie stories Campbell gives are bloody and dark. I wonder if "falls in love" was a euphemism on Campbell's part. One other point of interest is a song, titled "Skye Water-Kelpie's Lullaby" (Songs of the Hebrides) or "Lamentation of the Water-Horse" (The Old Songs of Skye). In this song, the singer mournfully begs a woman named Mor or Morag (depending on translation) to return to him and their infant son. This song has been interpreted as the story of a water-horse whose human bride has left him after realizing his identity. Outside the kelpie realm, there is another story with key similarities - the Scottish ballad "Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight." In this song, Isabel hears an elf-knight blowing his horn and wishes for him to be her lover. At that very moment, the elf knight leaps through her window and takes her riding with him to the woods. It’s all fun and games until he gets her into the remote wilderness, where he declares that he has murdered seven princesses and she will be the eighth. When begging for mercy doesn’t work, Isabel persuades him to relax and rest his head on her knee for a little while first. She uses a “small charm” to make him sleep, then ties him up with his own belt and kills him with his own dagger. Finlay’s heroine has strong Isabel vibes. Her suggestion of resting, and then her capture of her would-be kidnapper, is clearly parallel. When she calls on the bees to buzz and lull the water-horse to sleep, it's similar to Isabel's "charm." “Lady Isabel and the Elf Knight” is one member of a wide family of similar tales, although the plots vary and “Isabel” is somewhat atypical. Of course, the Elf Knight is not a kelpie. His native habitat is apparently the forest. However, in other versions, the serial killer’s method of killing is drowning (see "The Water o' Wearie's Well" and "May Colvin"). Francis James Child suggested that in these versions "the Merman or Nix may be easily recognized". A Dutch neighbor, “Heer Halewijn,” has been compared to a Strömkarl or Nikker. Unfortunately, as critics quickly pointed out, the logic fails since the serial killer dies by drowning in these versions, which would not make sense for a merman. The theory has stuck around despite lack of evidence. The rather unique “Lady Isabel” has faced scrutiny; the unclear origins have led to many different theories, and some scholars have even suggested that it was a fake written by its collector Peter Buchan. This will have to be a post for another time. Insofar as our current subject, “Lady Isabel” and the connected water-spirit theory are definitely old and well-known enough that Finlay could have been familiar with them. However, like the old kelpie stories, these ballads are not romances but cautionary tales. The stories in Folk Tales of Moor and Mountain are familiar folk tales, but they are all Finlay's retellings. Her "Water-Horse of Barra" is probably a reimagining of the older Barra water-horse tale. (Perhaps it's influenced by "Lady Isabel," although this might be more of a stretch.) In both Barra stories, a girl finds herself cornered by a kelpie in the form of a handsome man, and must figure out an escape as he lies sleeping. However, Finlay rewrote it with a gentler, family-friendly ending. Finlay's water-horse is tame and toothless even at the beginning: "he was very good-natured and never caused anyone harm." The only shocking thing about his diet is that he eats raw fish. Older tales often had sexual elements; a disguised kelpie shares a victim's bed to prey on her, and sleeping with your head in someone's lap is a euphemism for sex (note especially that the girl cuts her skirt off to escape). Finlay's water-horse never does anything so improper as sleep in the girl's lap; instead he stretches out in the heather to rest. In folktales, kelpies suck girls dry of blood, or devour them and leave only scraps of viscera. But Finlay's heroine is never in fear for her life. See her reaction: “He really is extremely handsome... but I have no intention of marrying a water-horse and spending the rest of my life at the bottom of a loch.” Finlay inverts the usual setup: here, the girl captures the kelpie. The kelpie is the one carried into a new realm and affected by their encounter. Not only is this ending more cheerful, but it ties in with Finlay's running theme. The time of magic ends to make way for a modern era. Supernatural power is exchanged for love, whether that love is romantic, familial, or belonging to a community. Regardless of its origins, Winifred Finlay's romantic tale of a good-hearted water-horse has earned its own place in modern folklore. This shows a shift in how we comprehend and retell these stories. In 19th-century storytelling, kelpies and changelings would have been totally irredeemable, definitely not beings you'd want to invite into your home. Now, however, you can find stories removed from folk belief where kelpies and changelings are the heroes and main characters. There's a growing tendency to give even the most terrifying monsters of legend a chance for redemption. Further Reading

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed