|

I recently saw someone cite A Basket of Wishes as an example of a romance novel cover, and it reminded me of something I noticed a while ago. And yes, this is another post on pillywiggins.

Among other appearances, these flower fairies showed up in a spate of romance novels through the 1990s and a little bit into the 2000s. First was A Basket of Wishes by Rebecca Paisley (1995). Then Twin Beds by Regan Forest (1996), A Little Something Extra by Pam McCutcheon (1996), Stronger than Magic by Heather Cullman (1997), Scottish Magic: Four Spellbinding Tales of Magic and Timeless Love (1998), A Dangerous Magic (1999), and Buttercup Baby by Karen Fox (2001). A Basket of Wishes and Buttercup Baby, the first and last in this list, share a number of similarities.

Beyond the rather by-the-numbers plot setup, one of the most striking similarities is the fairy heroine whose tears are gemstones. The idea of tears becoming jewels has its own Aarne-Thompson motif number, D475.4.5. It appears in the Grimms' tale "The Goose Girl at the Well." In the Palestinian story of "Lolabe," the heroine weeps pearls and coral. This trope is often associated with mermaids. "Mermaid tears" is an alternate name for sea glass. There's a Scottish legend - recorded in 1896 when adapted into a poem - that a mermaid's tears became the distinctive pebbles on the shore of Iona. In Chinese legend, mermaids weep pearls; this idea was recorded going pretty far back, for instance by fourth-century scholar Zhang Hua in his Record of Diverse Matters. Rebecca Paisley is the first person to apply this motif to pillywiggins. Karen Fox is the second. So far as I know, they remain the only two authors to do so. As far as differences, they do take place in different time periods. Buttercup Baby is about the pregnancy and slice-of-life fluff. A Basket of Wishes, on the other hand, tends more towards high fantasy and some drama with Splendor’s realm being in danger. Paisley's writing has a number of folklore references. Her pillywiggins (who are synonymous with fairies) live under a mound and tie elf knots in horses' manes. They are incredibly lightweight, like Indian tales of a princess who weighs as much as five flowers. They have no shadows, like Jewish demons and Indian bhoots or bhutas. Most intriguingly, Splendor reveals that her powers are not always limitless. She can't just vanish maladies like a stutter, an unsightly birthmark, or baldness, but must transfer them to someone else - which she does, giving those attributes to the book's antagonists. This harkens to the fairytale known in the Aarne-Thompson system as Type 503. In a common variation, two hunchbacks visit the fairies. One pleases the fairies and they reward him by removing his hunch. The second man is rude and greedy, and the fairies add the first man's hunch to his own. Karen Fox, on the other hand, builds a world based on old English literature: A Midsummer Night's Dream and 17th-century ballads about Robin Goodfellow. She uses “pillywiggins” as a singular noun (which is not uncommon as a variant spelling). Unlike Paisley's version, Fox's pillywiggins are not a name for fairykind as a whole, but a specific subspecies. Fox's use of Ariel as the pillywiggin queen points to Edain McCoy's Witch's Guide to Faery Folk (1994). McCoy was the first to give Ariel as the name of a queen of pillywiggins, and Fox is far from the only author to have followed suit. McCoy's book has been subtly but deeply influential, with large portions posted online by 1996. A now-defunct quiz titled "What type of female fairy are you?", online around 2002, advises the user that "Most of the information used in this quiz was taken (in some cases verbatim) from A Witches' Guide to Faery Folk by Edain McCoy." Pillywiggins are one possible result on the quiz. The new mythology of pillywiggins has been spread mainly through the Internet through sites like this. Creators in the 80's, 90's and early 2000's, like McCoy, Paisley and Fox, used them as basic winged flower fairies. Later authors played with this. In 2011, Julia Jarman made Pillywiggins a singular fairy who stands out from her glittery peers as bold and boyish. The pillywiggens of Marik Berghs’ Fae Wars novels (2013) are “fierce hunters” who ride on birds. Even in these fiercer examples, though, there remains a focus on their minuscule size and "cuteness." Jarman's heroine receives doll clothes. Berghs' pillywiggens speak in chirps and eat crumbs. The attraction of the pillywiggin lies partly in its ability to put a name to the modern archetype of the cute, winged flower fairy. In the first known appearance of pillywiggins, they were listed as a type of flower fairy. However, when it now appears in modern Internet parlance, pillywiggin is the name for the flower fairy category. Despite their similarities, Paisley's and Fox's works both show slightly different takes on pillywiggins. Nearly every author seems to have their own unique approach, while still subtly building up a new piece of folklore. At this point, I feel that if a pre-1970s source for flower-fairy pillywiggins ever shows up, it will be completely unrecognizable compared to the newly evolved myth. Other posts in this series

1 Comment

If there's one historical mystery I'm dying to know the answer to, it's what was going on with General Tom Thumb's baby. The baby hoax has become one in a long litany of P. T. Barnum's frauds and humbugs. To cut a long story short, two of his performers, under the stage names General and Mrs. Tom Thumb, posed with a baby and performed with it to fake the impression that they had had a child. One website I encountered suggested that as part of the offensive hoax, a different baby was used for every single publicity photo. Another took the opposite tack: that the Thumbs really had a daughter, but that another baby was borrowed for photos because the real baby wasn't "photogenic" enough. Confusion abounds. So now, I'm going to take a plunge into the actual news articles from the time.

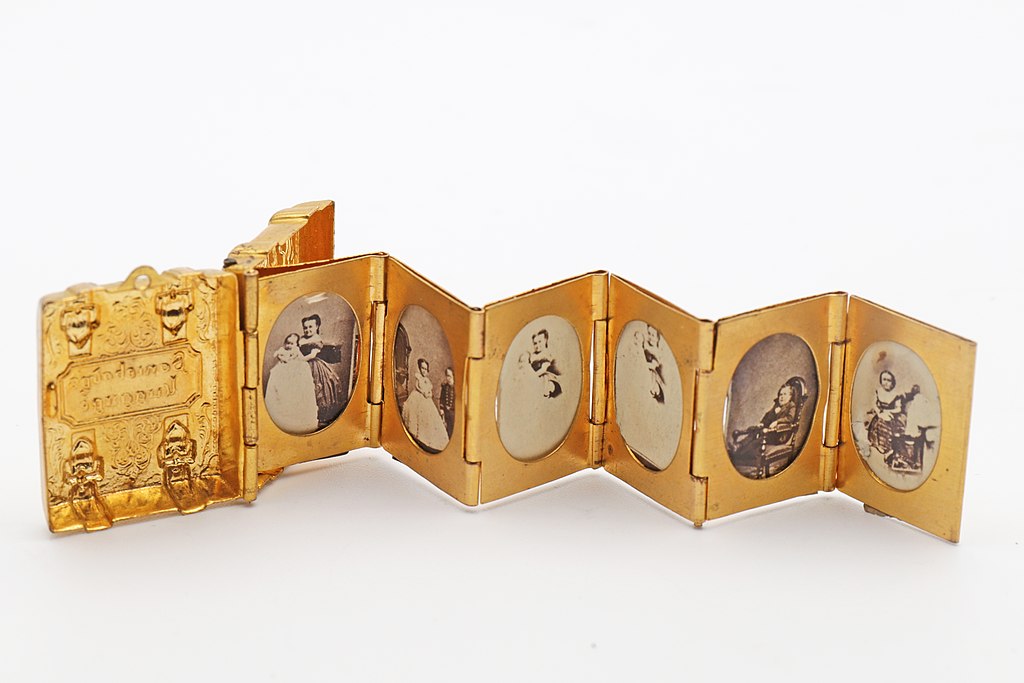

Charles Sherwood Stratton, or General Tom Thumb, began his life as one of Barnum's most famous performers when he was about four years old. He and his wife Lavinia Warren - who Barnum "discovered" when she was 21 and Charles 25 - were little people. In December 1862, to drum up attention, Barnum coyly published letters dated December 1862, where he begged Lavinia to come work with him. This method seems to have worked well. In January 1863, Harper's Weekly raved about Lavinia's first appearance and crowed, "General Tom Thumb and Commodore Nutt are henceforth not without hope." From her first appearance, people were trying to pair her off. The showrunners wasted no time. Her wedding to General Tom Thumb was the following month, in February. The New York Times had all the details, from the design of Lavinia's gown to the list of wedding gifts - “all of which were very nice, excepting the common affair of a cradel [sic] with which some person of little wit and less modesty encumbered the table.” For contemporaries, the idea of the Strattons reproducing was both engrossing and taboo. In the Sketch of the life, personal appearance, character and manners of Charles S. Stratton, the man in miniature, known as General Tom Thumb, and his wife, Lavinia Warren Stratton, an 1863 pamphlet possibly penned by Barnum himself, the Strattons were called a "mimic miniature Adam and Eve." The writer pondered whether they should be "the inventors of a race of humanity which . . . shall grow small by degrees." The Strattons began entertaining, giving their "levees" and often posing in their wedding costumes. They worked with fellow performer Commodore Nutt and Lavinia's younger sister Minnie. However, the rumors had begun, which was doubtlessly what Barnum had hoped for all along. On 15 December 1863, the South Australian Register noted, "The American papers record that the wife of General Tom Thumb is enceinte." The Strattons were performing through November, December and January. The New York Reformer. February 09, 1864. "Mrs. Gen. Tom Thumb became a mother a few weeks since. Tom is said to have danced a hornpipe at the announcement." The Daily Ohio Statesman. February 16, 1864. “‘Mrs. Tom Thumb,’ says the Boston Post, ‘is a mother.’ ‘The Post is more premature than the Princess of Wales,’ responds the Cincinnati Commercial, and says to the Post--”Don’t be in a hurry about the little Thumb.’ Of course the Commercial knows, or ought to know, all about the delicate point, as Mrs. Thumb is on exhibition in that city.” The Quad-City Times, Davenport, Iowa. February 20, 1864. "Mrs. General Tom Thumb is reported to have become a mother, to the great joy of the General." Tri-states Union. March 4, 1864. "If the report be true, why, look out for a profitable show in six or eight months - Tom Thumb, and Tom Thumb's Wife, and Tom Thumb's Wife's Baby!" Liverpool Mercury, etc. Tuesday, March 8, 1864. "The wife of General Tom Thumb was delivered of a son and heir on the 22nd of January.” The Sacramento Daily Union, March 14, 1864. "Mrs. General Tom Thumb, it is said, gave birth to a child on the 12th of January." The Burlington Weekly Sentinel. March 18, 1864. "The newspapers (scaly fellows) report that Mrs. Gen. Tom Thumb was -- and has --. It turns out, however, to be a hoax... So Tom didn't dance the hornpipe after all, as was reported. In other words, there isn't any little Thumb yet." The Troy Weekly Times, March 19, 1864. "A Connecticut paper [Charles was from Connecticut] says that 'the statement which has appeared in numerous journals to the effect that Mrs. Tom Thumb had become a mother is somewhat premature as we are assured upon the very best authority that the great event is not expected to occur before the month of July next.'" Rumors flew from place to place, varying from paper to paper and by word of mouth. The baby might be a boy. The birth might have occurred in January, or it might be expected in July. During all this, the Strattons were apparently still performing. In October 1864, the troupe departed for a tour in England. They arrived in Liverpool on the steamship City of Washington, and with them was their baby. The Daily Post from Liverpool reported on November 12th, 1864, that the Strattons were accompanied by their "infant daughter" who would be "twelve months old on the 5th of December." The birthdate could just be the result of careless reporting. However, Barnum had advertised a five-year-old Charles as an older child to make him seem smaller. Maybe this was the same principle. All that aside, December 5, 1863, was the official birth date for the Thumb baby. A medal produced by the Barnum Museum shows an image of the family trio, and refers to the Strattons' daughter with that birthdate. The Sketch of the Lives of C. S. Stratton and his wife, etc (1865) repeats this: "On the 5th of December, 1863, Mrs. Stratton gave birth to a female infant, weighing at the time of its birth but three pounds." The baby was an instant hit, but the main question was how big she was. Charles and Lavinia were both average-sized infants but stopped growing at a young age. It would have been impossible to say whether the baby was done growing. Everyone had an opinion, though. The Morning Post in London said that she "partakes of the proportions of her parents." The Lancet wrote "The diminutive pair seem very proud of their offspring; whether it will be of the same Liliputian stamp we cannot at present say." And the Morning Herald called the child "heiress to the Stratton name and fortune, but not to the Thumb inches, if we may judge by present looks, for the little girl (called Minnie, after her aunt) is just a year old and already weighs 7 3/4 lbs." In the midst of all this, the baby had a name: Minnie Stratton, after Lavinia's beloved sister and fellow performer. On November 24, 1864, the Morning Post in London reported the Tom Thumb company's visit to the Prince and Princess of Wales. "The Princess of Wales bestowed much attention on the pretty little infant." The baby was "a pretty little girl, with light silken hair and a vivacious disposition," according to the Soldiers' Journal on December 14, 1864. The London Daily News, on December 20 1864, reported the Thumb party's performance at the Crystal Palace, where Baby Minnie was a hit. "The ladies enjoyed the luxury of a close inspection of the General's baby, and of overwhelming the poor little thing, much to its annoyance, with kisses." The reporter seems taken with the comedy of Charles Stratton being defeated by a fretful baby: "He made several valiant attempts to induce her to put on a pair of gloves nearly an inch long, and when at last he had had his ears sufficiently boxed, and the gloves thrown in his face for his pains, he made a very skilful retreat, and left the baby in possession of the field. " The reporter also remarked on the resemblance of the child to her parents. The advertisements continued, milking the Stratton family image for all it was worth. A letter published in the Times-Picayune in January 1865, and in the Santa Fe Weekly Post, in February 1865, described meeting the performers in Paris. The description of Minnie Stratton ends on an odd note. "[T]he lion of the party was the baby, a little girl twelve months old, looking the picture of health and, without exaggeration, extremely beautiful. The face has nothing of the dwarf about it, but my observation that she looked as big as an ordinary child of her age was not approved by the secretary, who assured me that the weight was something very far below the average, and, lifting up the expensive lace frock, showed me her little feet in red morocco shoes, which are not larger than those of a moderate sized doll. My inquiry whether the child was expected to grow up a dwarf, met with the cautious answer that there was 'no precedent.' This is, I believe, true. There is, I am pretty sure, no instance of such a small child as Tom Thumb and his wife having been the progenitors of a child. I venture to prophecy, however, that Miss Minnie Stratton (that is the name of the infant) will, if she lives to attain her majority, be nearer the ordinary size of mankind than that of her parents. I do not believe in the foundation of a race of pigmies." In August 1865, the Sacramento Daily Union reported on the party's visit to Windsor Castle, and actually gave an idea of what their performances were like. "The performance commenced shortly before four o'clock, being opened by Mrs. Tom Thumb with a song, "My Native Land." This was followed by "Impersonations of Billy O'Rourke" and "Napoleon Bonaparte" by General Tom Thumb. Mrs. Stratton, the General's wife, then introduced her infant daughter." The baby was yet another part of the act, to be brought out, passed around and cooed over between songs and jokes. But it was not to last. The Morning Post reported on 26 September 1866 that "Yesterday Minnie Stratton— or, as the child used to call herself, Minnie Tom Thumb— the infant daughter of General and Mrs. Tom Thumb, died at the Norfolk Hotel, Norwich." She would have been roughly two years old. The Norfolk News reported on her burial in the local cemetery. Cause of death was given as "gastric fever;" other papers reported it as "inflammation of the brain." Although the funeral was supposed to be private, it was mobbed by about a thousand people. "It is said to be the intention the General to apply for an order to have the corpse removed to America, his native land, when he himself returns.” The grave still stands in the Norfolk cemetery, and Minnie is listed in the local death records as the daughter of Charles Stratton. Newspapers reported cancellations of performances "owing to the death of little Minnie Stratton." The Strattons' fellow performers Commodore Nutt and Minnie Warren were on their own for several shows. Minnie Stratton's death was treated seriously. And that was it. The party went back to performing. In July 1878, Minnie Warren died in childbirth. Her baby, who also died, weighed six pounds. According to obituaries, Minnie had expected a miniature baby and sewed clothes based on doll patterns, "one-sixth the size of garments for ordinary babies." Her husband, however, as well as P.T. Barnum, had been apprehensive, according to the news. One obituary for Minnie Warren mentioned "the memory of the spurious Thumb baby." At this point, at least some Americans had decided that Minnie Stratton - whose heyday took place an ocean away - was a hoax. But the troupe itself made no such admission. Sylvester Bleeker, the Strattons' manager for many years, gave an 1882 interview mentioning the child. "Mrs. General Tom Thumb's baby was one of the prettiest little girls I have ever seen...It was a perfect picture of Minnie Warren, Mrs. Thumb's sister, and everybody knows how beautiful she was. Lavinia Warren was married to Charles S. Stratton (Gen. Tom Thumb) in 1863... The baby was born a year after, and the event was heralded all over the world. The child was like other children in size, but was prettier than the average, and was healthy and bright. Mrs. Thumb idolized her baby, and when death took it from her, the blow was almost more than she could bear. The little girl lived to be two years and eight months old, and died of gastric fever in Norwich, England. She was made a great pet by the English ladies, who were in the habit of giving her sweet meats and candies, and I think this was one of the causes that led to little Minnie's death." Charles Stratton's obituary in the New York Times, published July 1883, mentioned that "He had one child, born in Brooklyn 14 years ago, who only lived two years. It was of ordinary size.” (This would place the child’s birth in 1869 and death in 1871.) An odd sidenote: the Galveston Daily News, in August 1892, reported the wedding of another couple of performers with dwarfism. There, the writer mentioned in passing "They say . . . that Tom Thumb's son is nearly 6 feet high and that he is very proud of his little mother.” Then, in April 1901, an article was published in several papers titled "Tom Thumb's Widow Reveals Secrets of the Show." It claims that about a year after the Strattons' wedding: "an innocent little item was smuggled into the English papers to the effect that the Tom Thumbs had A Baby Son. It was widely copied, and by the time Mr. Barnum and his midget charges arrived the British public was worked up to a considerable degree of expectancy as regarded the baby. In Egyptian Hall, London, they were exhibited all over again - General Thumb, Mrs. Thumb, and the baby. The performance was repeated all over Europe, and the Thumbs came back richer than they had ever been before. People have occasionally wondered since then whatever became of that baby! ... "I never had a baby," [Lavinia] declared recently. “The Exhibition Baby came from a foundling hospital in the the first place, and was renewed as often as we found it necessary. A real baby would have grown. Our first baby - a boy - grew very rapidly. At the age of four years he was taller than his father. This would never do... We appealed to Mr. Barnum. He agreed with us. He thought our baby should not grow. Thus we exhibited English babies in England, French babies in France, and German babies in Germany. It was - they were - a great success." This article is widely quoted, but does nothing but raise questions. Early reports did say that they had a son - but when they went touring, it was with a baby girl. This also implies they paraded around with a baby for over 4 years. They were married at the beginning of 1863 and could not have debuted their baby until at least November 1863. The baby's death was announced in England in September 1866. There wasn't time for a baby boy to grow to age four and for more babies to follow. Something here is fishy. Was Lavinia misremembering her past?What was going on here? And "taller than his father"? This phrase is reminiscent of the declaration that Minnie Stratton, age one, weighed “7 ¾ lbs., which we take it is more than her father weighed at the same age.” That’s as much as an average newborn weighs today, so I’m not sure what they were trying to say there. It is clear that the marketing team was trying to push the idea that the baby was unusually small, but observers were not always convinced and there was some arguing over whether the baby would grow. Now we’ve got an affirmation that the baby did indeed grow. Or is this line, perhaps, an echo of the rumor that Tom Thumb’s son grew up to be six feet tall? Lavinia would be of no further help. In 1906, she wrote a series of five articles for the New York Tribune Sunday Magazine, and went on to publish an autobiography. She never mentioned the baby, though she included many details about her tour through Europe beginning in 1864. That year, newspapers had made much of the baby - but in Lavinia's account, there's not even a hint of any baby's existence. No real baby, no hoax baby. No babies whatsoever, except for her sister's tragic pregnancy. In April 1946, Edna L. Bump - wife of Lavinia's nephew Benjamin J. Bump - wrote a letter to the editor of New York Times regarding an article on the Strattons. "The Tom Thumbs never had a child. The child shown in that picture was borrowed for a publicity stunt when they were employed by Barnum." Benjamin mentioned the baby hoax in his own pamphlet about the Strattons, "The Story that Never Grows Old," in 1953. Alice Curtis Desmond, in her 1954 book Barnum Presents General Tom Thumb, quoted Benjamin on this strange "family secret." In Desmond's account, Barnum was solely responsible for the hoax. "He hired infants wherever the circus happened to be, with their mothers as nursemaids" (page 215). (Note that these are not foundling hospital babies; their parents are along for the ride.) Here, Lavinia was a victim of the hoax, broken-hearted by her inability to have a child. Gradually, this new narrative spread. People stopped mentioning a child born to General Tom Thumb, and instead told the story of a manipulative baby-exploiting hoax. The rediscovery of Minnie Stratton's grave and death records came as a shock when publicized in the BBC documentary The Real Tom Thumb: History's Smallest Superstar (2014). One online article declares that the baby in the photographs was actually Lavinia's nephew "Gus." I have been unable to find any support for this suggestion. However, with research through ancestry.com, I did learn that Lavinia had a nephew named William Sherwood Wilbar, or Willie, born to her sister Sarah on May 9, 1864. The same time as those birth rumors. There’s nothing to indicate that William ever posed as the Strattons’ child for photos. However, it’s intriguing that he shared a middle name with Charles. Could the rumors have been colored by the fact that Lavinia’s sister was pregnant, and that the Strattons might have been seen in the vicinity of a newborn boy? I still hold that Lavinia probably could not have carried a child to term. If it was anything like her or Charles, it would have been a fairly large baby and complications would easily have arisen. That was exactly how her sister Minnie later died. The official narrative was that Lavinia gave birth to a three-pound girl. Improbable, but Minnie Warren seems to have bought into the idea. Lavinia was also touring during the time a Stratton baby would have been born. It makes sense for the baby to be a fraud, although that makes the grave mysterious. But the later account of the fraud is just as confusing and doesn't match up with the timeline shown by newspapers. A big part of the hoax is the photos that are left. These would have been sold as souvenirs. I’ve been collecting all the photos I can of the Stratton family, and there are two groups in particular that seem to have been taken in long photo sessions at different periods in time. You can identify two studios, with common set pieces. The clothes – particularly Lavinia’s gowns – are also clear markers. As for the baby, there are clear differences between the two groups of photos, BUT it is hard to say whether we are looking at two different children, or one child at different stages of development. There is no obvious “OMG that’s a completely different kid!!!” There’s no huge difference in facial structure. In the first group of photos, attributed to the famous Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, the baby lies cradled in Lavinia’s arms, wearing a long christening-syle gown as she gazes directly at the camera. (A photo where she is smiling - here - is the most-reproduced picture of the trio). Her long wisps of hair are visible in several copies, and in one colorized photo have been painted bright yellow. The image at the top of this post has several pictures of the Mathew Brady baby. In the second group of photos, which I believe were taken by the London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company, the baby now sits unsupported, and is much more active (typically seen with face slightly blurred in movement, often looking away from the camera). Her hair looks like it is parted in the middle and smoothed back. She wears dresses with wide skirts. Her size relative to the Strattons does seem roughly the same as before, but it’s hard to tell due to the long gown used in the previous photos. You can see one such photo in this post. You can find more photos with a simple Google search. What do you think? Are there different babies in the different photos? What was going on with Lavinia's mysteriously inconsistent interview? And who is the child buried in Minnie Stratton's grave? |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed