|

I have a few pages, including "The Little Folk," "List of Fairies," and "The Denham Tracts," related to fairy lore. They're a work in progress. I've found that sources are often hard to sort through. A small superstition from one area can easily bloat and transform into a supposedly famous Europe-wide tradition. Mistakes are repeated as fact until the real facts are forgotten. For one example: hyter sprites are mentioned in a few encyclopedias as small fairies with sand-colored skin and green eyes, who are protective of children and, most notably, can transform into sand martins. The most well-known source for these was Katherine Briggs' Encyclopedia of Faeries (1973), based on an account by folklorist Ruth Tongue. In 1984, Daniel Allen Rabuzzi wrote an article, “In Pursuit of Norfolk's Hyter Sprites," trying to chase down the original tradition. When he interviewed natives of Norfolk, he found no tradition of little werebird fairies. Instead, the phrase hyter, hikey or highty sprite was an idiom or nickname, most frequently used for a bogeyman ("Don't go out after dark or the hikey sprites will get you!") Everyone imagined them differently. One account described them as human-sized, batlike, threatening figures. Also, it turns out that although Ruth Tongue was a wonderful storyteller, she may have straight-up invented a lot of the stories she "collected." A class of fae similar to hyter sprites are "pillywiggins," tiny spring flower fairies in English and Welsh folklore. They have wings and antennae like insects. Though protective of their garden habitats, they are peaceful creatures who (unlike most fairies) don't bother much with humans or pranks. They live in groups, ride on bees, and their queen is named Ariel. At least, that's what you'd gather from the handful of books that mention them.

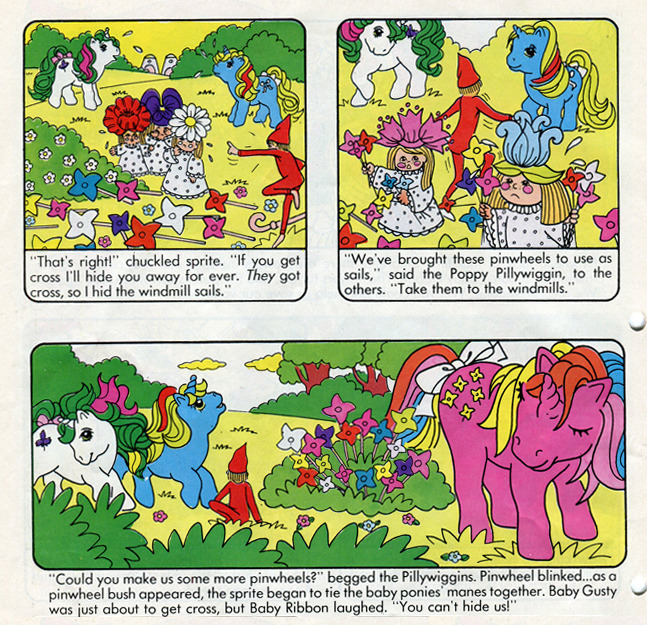

I should mention that many of these books are terrible at citations. Many of them don't cite anything, they just have one giant bibliography with no way to tell what came from where. Dubois's book is rife with misspellings, and Bane's with mistakes and misattributions. It looks like Dubois and McCoy were both elaborating on the brief description of Fairies & Elves, with very fanciful entries of their own. I have not found any supporting evidence for McCoy's "Queen Ariel." Here, McCoy actually seems to have cribbed from Shakespeare's Tempest (1610). McCoy's pillywiggins are bee-riding spring fairies, and her Queen Ariel "often rides bats, and is blonde and very seductive. She wears a thin, transparent garment of white, sleeps in a bed of cowslip, and can control the winds. She cannot speak, but communicates in beautiful song." Compare The Tempest, where a spirit named Ariel sings, Where the bee sucks, there suck I. In a cowslip’s bell I lie. There I couch when owls do cry. On the bat’s back I do fly After summer merrily. Merrily, merrily shall I live now Under the blossom that hangs on the bough. Still, later writers cited Dubois' and McCoy's work as folklore fact. Bane's encyclopedia of folklore and mythology has an entry on pillywiggins based on McCoy's description. Pillywiggin queen Ariel appears in the novels Buttercup Baby by Karen Fox (2001) and Alexander of Teagos by Paula Porter (2010). In 1986, a UK-published My Little Pony comic featured pillywiggins as non-winged flower fairies. It was apparently written for Wayne and Claire of Hanham, Bristol. There is an extensive article on pillywiggins on the French Wikipedia. But these are supposed to be English fairies - why is there more on them in French than in English? Even the talk page raises questions about this, besides pointing out that all sources are very recent and do not point to pillywiggins being a part of tradition. The most recent edit, by Tsaag Valren on June 6, 2011 says, "...after a week of research, seeing that I could find nothing more, I asked Pierre Dubois himself how he got his sources. He told me broadly that he wrote from popular English songs and discussions. As for the other works on the fairies, in general they repeat themselves: pillywiggin is the fairy of flowers, and not much more!" Although they've gained a tiny foothold into literature, I have yet to find the word pillywiggin recorded in anything before the 1970s. This is in stark contrast to other British and Welsh fairies such as pixies and brownies, which were first described hundreds of years ago, and which have variations in many different places. There could certainly be an oral tradition of pillywiggins going way back, but in that area of the world, it seems unlikely that it would have escaped notice. I can only track the name itself back to Arrowsmith's Field Guide to the Little People. It mentions pillywiggins briefly, in a list of other tiny fairies, and says they're from Dorset. My research into Dorset folklore has not yet discovered any mention of pillywiggins. Arrowsmith's bibliography lacks details, so it's hard to say where she found this information. She also mentions Ruth Tongue's hyter sprites, which as already noted, have a shaky basis in folklore. However, there are plenty of traditions of fairies being related to oak trees and plants including bluebells, thyme and foxgloves. Oak trees have magical qualities in British lore, and there's an old poem with the line "Puck is busy in these oakes." Many other plants were named for fairies. Foxgloves in particular are often connected to fairies and witches. For instance, the Welsh ellyllon are “pigmy elves” who wear foxgloves on their hands. The idea of miniature fairies goes at least as far back as the description of the one-inch-tall portunes in Gervase of Tilbury's Otia Imperiale, around the year 1210. Around 1595, A Midsummer Night's Dream gave us fairies who have power over nature, crawl into acorn cups and hang the dew in flowers. In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen's Thumbelina emerged from a flowerbud and later encountered flower spirits with fly's wings. In the first half of the 20th century, Cicely Mary Barker's illustrations and Queen Mary's interests truly popularized the idea of tiny, benevolent flower fairies. As it happens, Pillywiggin does sound a lot like another fairy name: Pigwiggin or Pigwidgeon. You might recognize this word as the name of a pet owl in the Harry Potter series. It is a name for a tiny, insignificant creature. There are lots of different theories on its etymology, but Pigwiggin became famous as the name of a fairy knight in the 1627 poem Nymphidia. From there, pigwidgeon emerged as an obscure name for a miniature fairy or dwarf. The English Parnassus (1657, Josua Poole) includes a list of Oberon and Mab's courtiers, including "Periwiggin, Periwinckle, Puck." This is based on Nymphidia with some misspellings. This textual error could be an important clue. Maybe pillywiggin, like periwiggin, is just a misspelling of Pigwiggin. From there, it was picked up by other researchers and took on a life of its own. I will say that Pillywiggin is a fun name, and I don't really mind using it for the modern flower fairy. For the moment, my search has come to an end, but I will be keeping an eye out for further clues. If you have any insight on this subject, let me know! Further reading

Part 2: What are Pillywiggins? Revisited Part 3: Pillywiggins in Pop Culture Part 4: Pillywiggins, Etymology, and ... Knitting? Part 5: Diamonds and Opals: Two Romances Featuring Pillywiggins Part 6: Pillywiggins: An Amended Theory Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

2 Comments

Bunny

11/4/2017 10:33:23 pm

Thanks for the article. My late grandmother, originally from Wimborne, Dorset, would bemoan those pesky Pillywiggins whenever something went missing or awry. I haven't been able to find much information about them, and appreciate the effort you've put into the article.

Reply

Writing in Margins

11/5/2017 06:44:05 am

Thank you so much for commenting. That kind of oral tradition is exactly what I've been trying to find, so this is a huge help!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed