|

What’s the deal with Kensington Gardens and fairies?

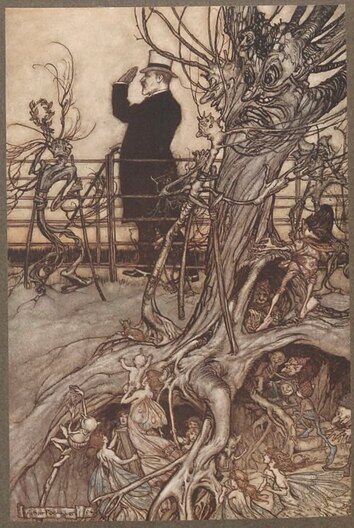

Kensington Gardens in London were originally part of a hunting ground created by Henry VIII. In the early 1700s, Henry Wise (Royal Gardener under Queen Anne and later King George I) made numerous adaptations including turning a gravel pit into a sunken Dutch garden. Queen Caroline ordered additional redesigns in 1728. In the 19th century, the Gardens transitioned from the royal family's private gardens to a popular public park and a place for families with children to walk or play. Over the years, the gardens have gained associations with fairies in literature. This can be traced to the 18th century, when Thomas Tickell (1685-1740) wrote the 1722 poem "Kensington Garden," a mock-epic starring flower fairies and the classical Roman pantheon, which gave the location a mythical origin. The basic plot is that the fairies once lived in that location, until King Oberon's daughter Kenna fell in love with a mortal changeling boy named Albion. This, naturally, led to war. Albion was killed, and while the fairies scattered across the realm in the brutal aftermath of the war, Kenna remained to mourn over his tomb. She eventually instilled royalty and architects with the inspiration for Kensington Palace's garden. Thus, the garden is based directly on the fairy kingdom that once stood there, and the name "Kensington" is derived from the fairy princess Kenna. "Kensington Garden" was evidently influenced by Alexander Pope's Rape of the Lock (also known as the first poem to give fairies wings). Both are mock epics imitating Paradise Lost, but with overwrought adventures of comically tiny fairies. Tickell's fairies are larger than Pope's, though, standing about ten inches tall. (Tickell and Pope were familiar with each other; both produced translations of the Iliad in 1715, and this caused a clash as Pope suspected Tickell of trying to undermine him.) Note that the title of the poem is "Garden," not "Gardens"; the modern Kensington Gardens were yet to begin construction. The poem was specifically focused on Henry Wise's sunken garden, explaining how that exact spot once held the "proud Palace of the Elfin King." Despite the faint note of absurdity in the tiny flower sprites, Tickell was working to create a mythical origin for Britain and its notable sites. Tickell's Albion is the son of a faux-mythical English king, also named Albion, who was the son of Neptune. Albion, senior, appeared in Holinshed's Chronicles in the 16th century, and in the fantasy works of Edmund Spenser and Michael Drayton. Tickell fashioned a story in which "the myths of rural and royal Kensington united" (Feldman, Routledge Revivals, 15). Inspired by the artistic renovations of the palace garden, he created a mythical prince from the dawn of England, whose fairy lover still watched over the modern royal family's home. He wanted to build a mythology showing the British royals' ancient pedigree. It was all part of England's grand heritage, leading back to classical Greece and Rome. Kenna resembles a patron goddess, but you can also see in her an idea of past English monarchs who might not have had children of their own, but whose influence was still felt. Tickell's influence shows in other works in the years following. James Elphinston's Education, in Four Books (1763) created a verse description ostensibly of education in general. When he got to the subject of Kensington House (a boys' school which he ran from 1756 to 1776), he described the location in grandiose terms as "Kenna's town... where elfin tribes were oft... seen". (p. 129) The description of the town echoes Tickell's poetry. Thomas Hull (1728–1808) wrote a masque called "The Fairy Favour" in 1766. It ran in 1767 as the scheduled entertainment for the Prince of Wales' first visit to Covent Garden. This short play is set in a realm called Kenna. As in Tickell's poem, there are fairies named "Milkah" and "Oriel", although in different roles, and changelings are important. (Interestingly, there were multiple plays written for this occasion, and I'm wondering if the playwrights were given a theme. Rev. Samuel Bishop wrote "The Fairy Benison," which also features Oberon, Titania and Puck celebrating the arrival of the Prince of Wales and blessing him. However, the managers preferred Hull's take on the subject, and that was the one that was presented before the royal family.) Since then, Tickell's poem has faded from the scene. It popped up now and then. A mention of the poem made it into Ebenezer Cobham Brewer's 1880 Reader's Handbook of Allusions. An 1881 book on the park was titled Kenna's Kingdom: a Ramble Through Kingly Kensington. Around 1900, there were a couple of resurgences of Kensington Gardens' fairy connections. First was The Little White Bird by J. M. Barrie, published in 1902. The story was Peter Pan's first foray into the public eye. In this early version, he was a week-old infant who escaped from his pram, learned to fly from the birds, and went to live with the fairies in Kensington Gardens. In 1903, as thanks for The Little White Bird's publicity, Barrie received a private key to Kensington Gardens, and in 1907, several chapters of the book were published on their own under the title Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens. As early as 1907, John Oxberry wrote in the magazine "Notes and Queries" that Barrie had "followed the example" of Tickell. There are certainly parallels. Both stories feature miniature fairies who live among the flowers in Kensington Gardens. In both stories, a human infant is parted from his family and comes to live among the fairies, taking on some of their nature in the process. There are some attractively similar lines; Tickell's colorful fairies resemble "a moving Tulip-bed" from afar, while Barrie's fairies "dress exactly like flowers" (although, in a reversal, they dislike tulips). British biographer Roger Lancelyn Green, however, emphasized that "there is no proof" and "there is no need to insist that Barrie had read Tickell's poem" (Green pp. 16-17). Miniature fairies clad in petals were generic ideas, everywhere in children's literature. As Green said, Barrie "could easily have arrived at the same conclusions without knowing of this earlier attempt to people Kensington Gardens with fairies." Barrie's strongest influence in using Kensington Gardens was probably that he lived nearby, and it was where he met the family who inspired him to write Peter Pan. Around the same time as Barrie, Tickell's poem got a second chance at popularity in the form of a sequel: the comic opera "A Princess of Kensington," by Basil Hood and Edward German. It debuted at the Savoy Theatre in London in 1903, and met with mixed success, running for only 115 performances. (Oddly enough, it undermines the original poem, with Kenna beginning the play by stating that she never really had feelings for poor deceased Albion and actually likes some other dude.) Kensington Gardens has embraced its fairy associations. A statue of Peter Pan was added to the gardens in 1912. In the 1920s, the Elfin Oak was installed. This was a centuries-old stump of wood, gradually decorated by the artist Ivor Innes with carvings and paintings of gnomes, elves, and pixies. With his wife Elsie, Innes produced a 1930 children's book titled The Elfin Oak of Kensington Gardens. Like their predecessors, the fairies of this book emerged by moonlight to dance and frolic. Was there a pre-Tickell association with fairies? Was there, as Lewis Spence wrote in 1948, "an old folk-belief" that "this locality was anciently a fairy haunt"? Although Tickell wrote in the poem that he had heard the story as a child from his nurse, Katharine Briggs expressed skepticism. He might well have heard fairy legends, and he certainly included some folklore in the poem, but "since he was born in Cumberland it is perhaps unlikely that his nurse had any traditional lore about Kensington Gardens" (The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, 183). Also note that Tickell was focused on some specific recent renovations to the garden, which wouldn't have had time to collect mythical status. In a book on the garden, Derek Hudson wrote that "Tickell seems to have been the first to establish a fairy mythology for Kensington" (p. 110). Despite all this, according to a writer in 1909, some people "have gravely taken... Kenna... as a real personage instead of a mere poetic myth." Tickell and Barrie both placed fairy kingdoms in Kensington Gardens. However, they did so for different reasons, and with different associations for fairies. For Tickell, the fairies were royalty. This was a long-standing English literary tradition. Spenser's Faerie Queene (1590) treated Queen Elizabeth as a fairy monarch, and Ben Jonson's 1611 masque Oberon, the Faery Prince depicted James I's son as Oberon. In 1767, when celebrating the Prince of Wales' first visit to Covent Garden, playwrights rushed to script plays in which Oberon and Titania welcomed him. The Fairy Favour, the one chosen for performance, actually greets the prince as the son of Oberon and Titania. That prince was King George IV. The same tradition continued with George IV's niece, Queen Victoria. The 1883 book Queen Victoria: Her Girlhood and Womanhood described the young princess in otherworldly terms: "Victoria might almost have been a fairy-princess, emerging from some enchanted dell in Windsor forest, or a water-nymph evoked from the Serpentine in Kensington Gardens" (emphasis added). Note that the Serpentine, a recreational lake, was added under the direction of Victoria's great great grandmother Queen Caroline. The royal family were described as fairies and gods in literature. The royal family lived in Kensington Palace. It was natural for Kensington Palace and its surrounding gardens, structured and developed under the royal family's direction, to be a fairy realm. As the 19th century progressed, this changed. In literature, Fairyland became more and more the domain of children. At the same time, Kensington Gardens became a public park and a place for children. Matthew Arnold's 1852 poem Lines Written in Kensington Gardens imagined the gardens as a forested realm for little ones, "breathed on by the rural Pan." James Douglas's 1916 essays, collected as Magic in Kensington Gardens, depicted the children at play in the gardens as "solemn little fairies weaving enchantments." Barrie's work is, of course, the gold standard, where Kensington is intertwined with fairies and eternal childhood. So far, Barrie's work seems more enduring than Tickell's. Although most people would probably associate Peter Pan's location with Neverland, the actual Kensington Gardens location now has references to Peter Pan such as the statue. Although both writers drew inspiration from the same location, officials embraced Barrie's work and made it part of the park's identity. SOURCES

5 Comments

In modern fantasy, the idea of the Seelie and Unseelie Courts - two opposing groups of the fae - has become popular. But where did this idea come from? What was the original inspiration? What do Seelie and Unseelie even mean?

Fae Divided into Sections First of all, there are various old references to different classes of fae which may oppose each other. The Dökkálfar ("Dark Elves") and Ljósálfar ("Light Elves") are contrasting beings in Norse mythology, with the first surviving mention from the thirteenth century. The Light Elves are fair and the Dark Elves are “blacker than pitch,” and the two groups are totally different in temperament. There are also the svartalfar (apparently the dwarves) but there’s disagreement over whether they are the same as the dokkalfar or not. 16th-century alchemist Paracelsus divided mythical creatures like Melusine, sirens, giants and pygmies into classes by the four elements (water, air, fire and earth). There was certainly a sense that there could be good or evil fairies. Reverend Thomas Jackson wrote in 1625, in A treatise concerning the original of unbelief, “Thus are Fayries, from difference of events ascribed to them, divided into good and bad, when as it is but one and the same malignant fiend that meddles in both; seeking sometimes to be feared, otherwhiles to be loued as God." Jackson took the stance that all fairies were equally evil tricks of Satan, but his argument still gives us a few crumbs of contemporary fairy beliefs. Hulden and unhulden were Germanic spirits and, beginning in the 15th century, also referred to the witches who consorted with them. The preacher Bertold of Regensburg (c. 1210-1272) exhorted the Bavarian people against belief in such things. There is also a Germanic goddess named Holda, although scholars have disagreed on which is older. The word may come from a German root meaning "gracious” or “kind.” There are also the huldra or huldrefolk from Scandinavian folklore, coming from a word meaning "hidden,” but for holden and unholden I lean towards the “kind” definition. So holden would be “the Kind Ones”, unholden “the Unkind Ones.” As far back as the 4th century, a Gothic translation of the Bible used the feminine word "unhulþons” for demons. This could possibly mean that "Unkind Ones" and hulþons as good counterparts were also around at the same time. I am not sure whether these “Kind Ones” were really kind, or whether this was a euphemism - but the presence of the very non-euphemistic "unholden" is telling. Both types were certainly demonized during Christianization. Bertold concluded that "totum sunt demones" (all are demons). In the 15th century, the singular character Holda began to appear among other denounced goddesses in the Diana/Herodias crowd. Centuries later, Jacob Grimm noted that witches' familiars might be "called gute holden [good holden] even when harmful magic is wrought with them”. Now let's look at the most famous example of contrasting fairy groups: the Seelie and Unseelie. The Seelie and Unseelie Courts The Seelie and Unseelie Courts are Scottish names for good and bad fairies. Seelie means blessed or lucky and ultimately comes from the Germanic "salig"; the same root gives us the German nature fairies called “Seligen Fräuleins.” "Seely wight" or "seely folk" was an old term for fairy beings, roughly equivalent to Good Neighbors or Fair Folk. Note that in this case, these names were not meant to be taken literally; they were names meant to appease the temperamental and dangerous fae. In one poem, a spirit warns a human against calling it an imp, elf or a fairy. "Good Neighbor" is an acceptable term, and "Seely Wight" is ideal: "But if you call me Seely Wight, I'll be your friend both day and night." In Lowland Scotland in the 16th century, some witchcraft and folk magic centered around the seely wights. Researcher Carlo Ginzburg argued that there were worldwide parallel traditions of folk healers who believed that they left their bodies to travel at night with friends and/or spirits. In these night journeys, they ensured a good harvest for their village by battling witches or even traveling to Hell. Usually these meetings took place on specific nights of the year. The most well-known are the Italian Benandanti (Good Walkers). Some of these cults were connected to fairies. The Sicilian "donas de fuera," or "ladies from outside," derived their name from the spirit beings they were believed to travel with. 13th-century bishop Bernard Gui instructed inquisitors to investigate mentions of night-traveling "fairy women, whom they call the good things [bonas res]." Not all groups had stories of protecting the harvest. Some, like the donas de fuera, were simply supposed to meet up and hang out on certain nights. Ginzburg's theory has met with some criticism, but it is true that going back into medieval times, Christian bishops spoke out against women supposedly meeting at night with a goddess named Herodias or Diana or a whole host of ladies. Christian authorities denounced this as superstition or hallucination. William Hay, around 1535, gave a specific Scottish example: "There are others who say that the fairies are demons, and deny having any dealings with them, and say that they hold meetings with a countless multitude of simple women whom they call in our tongue celly vichtys." Based on the few surviving pieces of evidence, history professor Julian Goodare constructed a theoretical cult: in the 16th century, a group of Scottish women (and possibly some men) believed that they rode on swallows at night to join the seely wights, a group of female nature spirits akin to fairies. Despite their name, these beings weren't necessarily good. In 1572, accused witch Janet Boyman blamed the "sillye wychtis" for "blasting" and killing a child. The main problem with the theory, Goodare admitted, is fragmentary evidence. Seely wights apparently disappeared from belief before the real furor of witch trials ever started. However, in the 17th century, “wight” continued to be a common generic Scottish term for mysterious and powerful spirits that were perhaps not exactly fairies, but something harder to define. One accused witch spoke of “guid wichtis,” another of “evill wichts.” (Despite the descriptors, in both cases these creatures were blamed for striking young children with illness.) Another accused witch, Stein Maltman, spoke of "wneardlie" (unearthly) wights. But although “wight” remained popular, “seelie” faded from view. The seelie wights were apparently gone. Or did they just get a name change? "Seelie" survived in fairy names like Sili go Dwt, Sili Ffrit, and the Seelie or Seely Court. One of the Seely Court's earliest known appearances is the Scottish ballad of "Allison Gross," collected in the Child Ballads. They ride on Halloween, and their queen releases a man from a witch's curse. The presence of a queen is what makes it a seely court, a structured government under a ruler. They are no longer just random wights. The queen's actions imply a benevolent nature. The Child Ballads also include "Tam Lin," which features a less friendly fairy queen. In some fragments and scraps, which weren't complete enough to put as full versions, the fairies are called the "seely court." "The night, the night is Halloween, Our seely court maun ride, Thro England and thro Ireland both, And a' the warld wide." Note that in this version, there isn't a tithe to Hell. Although the tithe is in the most popular variant, a few feature all the fairies visiting Hell, or (as seen here) riding all over the world. The idea of the fairies roaming on a specific feast night (Halloween or an equivalent) does hearken to the idea of Diana's procession, the donas de fuera, and other such groups. The fairy queen would be equivalent to the other patron goddesses. Another connection - in the 1580s, a poet named Robert Sempill wrote the satirical “Legend of the Bischop of St Androis Lyfe.” One section described the witch Alison Pearson as riding on certain nights to meet the sillie wychtis. In real life, Alison Pearson's testimony included a tale similar to "Tam Lin." Although the term "seelie wight" doesn't appear in the trial records, she said she had been taken away by the fairies and taught the healing arts, but had to escape, for a tenth of them went to Hell every year. So Pearson talked about fairies making a journey to Hell, and a contemporary writer identified her fairies as seely wights. So we have print mentions of "seelie" fairies going back to the 16th century. On the other hand, I don't know of any appearances by the "unseelie" until 1819, when the Edinburgh Magazine featured an article titled "On Good and Bad Fairies." It described the Gude Fairies/Seelie Court and the Wicked Wichts/Unseelie Court; the Unseelie, it specified, were the only ones who pay tithes to Hell. (However, it was still foolish to anger even the Seelie.) I am not sure what the writer's sources were, though they may have drawn on traditions familiar to them. Other early mentions of the Unseelie Court were quotes of this article. Overall, Seelie and Unseelie Courts as opposed groups of fairies – and the word “unseely” applied to fairies at all – did not appear in print until comparatively recent times. [Edit 7/5/21: The "unseelie" word does go back to the 1500s! Scottish poet William Dunbar (c.1460-1530) described Satan's "unsall menyie" or "unhallowed number," and "The flytting betwixt Montgomerie and Polwart" (1629) mentions an elf and and an ape begetting an "unsell" or "vnsell".] For a while, I've believed "unseelie" is a neologism. Calling the fairies Seelie was originally meant to avoid their wrath; why would you call a fairy Unseelie? That's death wish territory. But although this theory seemed clear-cut to me at first, it may not have been that simple. Evidence shows that people did refer to "evil" or "wicked" wights as well as seelie wights. But I do have one wild speculative theory. The idea of good and bad spirits goes back a long way. Holden and unholden from Germanic myth (potentially as far back as the 4th century) might be a similar word formation indicating good and evil spirits who somehow mirrored each other. Some of Ginzburg's ecstatic cults were supposed to fight opposing groups. The Benandanti, for instance, fought the Malandanti (Evil Walkers). Let's extrapolate on the theory; say the seelie wights or Seelie Court were once a witchcraft tradition similar to those cults. What if they sometimes didn't just "travel" across the world or to Hell, but actually battled an opponent at some point in their journey - or had some kind of encounter, perhaps involving a tithe? What if those opponents were Unseely Wights? William Hay spoke of the seely wights' followers distancing themselves from fairies and calling them demons. What if the unseely wights were the forces of Hell? There is way more to the spectrum of witchcraft beliefs throughout medieval times - much more than can be tackled in one blog post. Anyhow, Seelie and Unseelie have since become common descriptors in both folklore guides and popular fantasy works. The names are a way to delineate between good and evil fairies, and do have at least some background in Scottish folklore. Even in the oldest sources, though, the lines blur between whether any of these beings are "good" or "evil." Both seelie and evil wights were perilous. Sources

Other Blog Posts

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed