|

Pictured: a pixie. (Also known as pixy, piskie, piksy, pexy, pigsey, or pigsnye.)

Pixie was originally just the Cornish term for a fairy. The exact etymology is unclear. It's been connected to everything from Picts to Puck. Anna Eliza Bray's A Peep at the Pixies (1854) uses the word for all sorts of fairy beings of varying size and appearance: will o' the wisps, fairy godmothers, brownie-style house elves, and ghostly phantoms. In modern times, pixie is frequently used for the cute, winged flower-type fairy (like pillywiggins). Disney uses "pixie" and "fairy" interchangeably to describe Tinker Bell's species. Marvel comics has a winged, pink-haired heroine named Pixie. However, I have found some websites and posts passionately declaring that pixies are not meant to have wings. Anyway, I decided to take a look at the earliest mentions I could find, to try to nail down as much as I can what a pixie was supposed to look like in folklore. Another creature from English folklore, the colt pixie, takes horse form to lead people astray like a will o' the wisp. "I shall be ready at thine elbow to plaie the parte of Hobgoblin or Collepixie" (The Apophthegmes of Erasmus; trans. Nicolas Udal, c.1564) As early as 1746, in An Exmoor Scolding, "ye teeheeing pixy!" was used as an insult.(Gentleman's Magazine, vol. 16) In 1787, in A provincial glossary: with a collection of local proverbs, and popular superstitions, pixy was simply defined as "fairy" and sourced to Exmoor. It also mentioned the Hampshire term "colt-pixy." The print references to pixies really started to spread in the 1800s. I've mentioned A Peep at the Pixies; there was the English Dialect Dictionary in 1880 and in more detail in 1902; Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology (1892); Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies (1890); Brand's popular antiquities of Great Britain (1905). But even as they grew popular in literature, writers were already lamenting that "the age of piskays, like that of chivalry, is gone" (Drew, The History of Cornwall, 1824) "Beautiful fictions of our fathers . . . They are flown before the wand of Science!" (Cabinet of Modern Art, 1829). The general consensus seemed to be that the pixies were little people or elves. In Malvern, as I found it by Timothy Pounce (1858) a character declares that a winged being "could not have been a pixie" (p85). By this period in time, though, people certainly had a concept of winged fairies. In 1867, there is a description of a "pixie court" with wings, in 1921 a poem with a reference to pixie wings, in 1927 a design for a pixie with wings. In 1953, Disney's Peter Pan brought with it Tinker Bell's "pixie dust." It was fairy dust in the original novel. Going back to the older resources on pixies, in Brand's Popular Antiquities, a pixy child is "human in appearance, though dwarfish in size." Other accounts called them "invisibly small." Many were strange-looking, hairy or animal-like, or dressed in rags, though they had a strong affinity with the color green. They sometimes stole children, and loved dancing and music. Pixies were laughing and mischievous; they might have been the souls of unbaptized infants. They liked to tangle horses' manes. Pixy-stools were a kind of mushroom - i.e., the pixies used mushrooms as chairs. Similar fungi were pixy-puffs and pisgy-pows (pixies' feet). To be pixy-led was to be led astray by mischievous spirits. To pixy was to glean leftover apples and walnuts after the harvest. (Report and Transactions - The Devonshire Association, 1875) All together, these descriptions paint an interesting picture. Really, to ask whether pixies should be shown with wings, is to ask whether fairies in general should be winged. I don't think anyone has nailed down the actual point at which people actually began to think of fairies as winged. Right now the earliest I know of is the illustrations for the 1798 edition of The Rape of the Lock. (See also Beachcombing's Bizarre History Blog.)

0 Comments

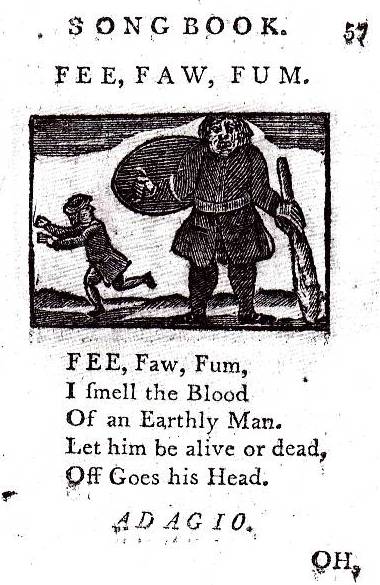

This incomprehensible phrase is most famous for appearing in "Jack the Giant Killer." Most versions adhere to basically the same model:

Fee-fi-fo-fum I smell the blood of an Englishman. Be he alive or be he dead I'll grind his bones to make my bread. What does "fee-fi-fo-fum" actually mean? Nobody knows. Although there have been theories. (Does fie mean a cry of disapproval, as in "Fie! Fie!"? Or does it come from the Gaelic word for "tasty"? I'm leaning towards "neither, just a nonsense phrase.") When Thomas Nashe mentioned it in Have with you to Saffron-walden (1596), it was already an old saying of obscure origin. "O, tis a precious apothegmatical Pedant, who will find matter enough to dilate a whole day of the first invention of Fy, fa, fum, I smell the blood of an English-man". (I have to say, I love that paragraph.) It also appears in King Lear (1605): Child Roland to the dark tower came, His word was still, Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man. In 1814, Robert Jamieson's version of Childe Rowland in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities had the Elf-king proclaim, "With fi, fi, fo, and fum! I smell the blood of a Christian man! Be he dead, be he living, wi' my brand I'll clash his harns frae his harn-pan! " [I'll dash his brains from his brain-pan] And in Tom Thumb (1621) - on this blog you know it's always going to come back to Tom Thumb - the hero encounters a giant who says, Now fi, fee, fau, fan, I feele smell of a dangerous man, Be he alive, or be he dead, He grind his bones to make me bread. So, by 1621, the rhyme was already associated with giants, and the colorfully gruesome idea of bone-meal bread was in existence. (Tom Thumb, as well as being the first fairytale printed in English, has lots of common fairy tale tropes, such as the fairy godmother.) So the phrase fee-fi-fo-fum has been around a long time. It first appeared in print in combination with Jack the Giant Killer when that story was printed in 1711. Regarding Childe Rowland, Jamieson recalled hearing a version in his childhood from a tailor: "the tailor curled up his nose, and sniffed all about, to imitate the action which "fi, fi, fo, fum!" is intended to represent." So maybe "fee fi fo fum" is meant to be some kind of onomatopoeia for smelling? I don't know how that would work, but I do find the different variations interesting. It looks like it was once more common to have only three syllables instead of four. Although this phrase is English, there are parallels to monsters detecting people by the smell of their blood in other countries. In Perrault's Popular Tales, Andrew Lang connects this theme to the Furies in Aseschylus' Eumenides. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed