|

"Tom the Piper's Son" is a nursery rhyme, with the first known version published about 1795 in a London chapbook. The titular Tom steals a pig, is beaten as punishment, and runs away crying.

There was another, longer poem about a Tom the Piper's Son, which dealt with him playing music wherever he went, but this is less known and has nothing to do with the more well-known version. The Ballad Index's writeup mentions a Lincolnshire text: Tom, Tom, the baker's son stole a wig, and away he run; The wig was eat, and Tom was beat, And Tom went roaring down the street. A wig was a kind of bun, explaining what it had to do with a baker's son, how a boy could carry it easily, and how it could be eaten. The notes suggest that this version is the original. It makes sense that someone could have heard the poem, thought of the other kind of wig, and corrected it to the more edible "pig." So the "pig" and "piper" elements could be simple oral mutations picked up as different people recited it, although it's impossible to say. There are a couple of versions, however, that particularly piqued my interest. Tom Thumb the piper's son, Stole a pig, and away did run ; The pig was eat, and Tom was beat, Till he ran crying down the street. (From Gammer Gurton's Garland (1810) p.35) And yes, in that version, it's Tom Thumb. It doesn't take much to go from "Tom, Tom" to "Tom Thumb." "Tom, Tom" is a bit too repetitive. "Tom Thumb" has more of a natural rhythm, and "thumb" is closer to rhyming with "son," at least in my accent. I find it interesting how these two seem to build in severity. The wig-and-baker version suggests a closer connection, perhaps that Tom was in a bakery run by his family, and that they punished him for his misbehavior. The pig-and-piper version gives more distance - Tom lacks even a faint claim to the pig. Thus the images in the shet music, with a policeman seizing Tom for his theft. This trend goes even further in a more violent version from Grey County, Ontario, published in The Journal of American Folklore in 1917. Tom Thumb, the piper's son, Stole a goose and away he run; The goose got caught, and he was shot, And that was the end of the piper's son.

0 Comments

In one early scene in Carlo Collodi's Pinocchio, the titular character plays hooky to visit a puppet theater. The act is a pair of wooden marionettes, Harlequin and Punchinello, arguing onstage. However, they soon recognize him in the audience, instinctively knowing his name and calling him their brother. They, and all the puppets from behind the curtains, call him up onstage and the play breaks down as they welcome him. The showman, Fire-Eater, plans to use Pinocchio as firewood, and then plans to use Harlequin instead. After Pinocchio talks him into relenting, the puppets dance all night. This scene is never mentioned again. The puppets here are just as alive as Pinocchio, but are treated as property rather than children, and there is nothing to stop their owner from throwing them on the fire if he's displeased. This scene baffled me when I first read Pinocchio, because it means he is not the only one of his kind and living puppets aren't uncommon. Maybe they were carved from similar pieces of talking wood. It fits in with the logic of the story. Ultimately, the scene contrasts the fate of a puppet with the fate of a human - and Pinocchio doesn't want to be a puppet. Pinocchio has a long hard road before he can become human. The other marionettes are content to remain what they are, but that comes at the price of freedom and security. He shows his noblest impulses of generosity and kindness while he's with them, but he doesn't have a great bond with them. Alexei Tolstoy's retelling of Pinocchio, The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Buratino, ran wild with the idea of other puppet characters. Here, Buratino has no desire to become a real boy, and at the same time has a much greater bond with the other puppets. His quest is to liberate them from their owner. More recently, the graphic novel Pinocchio, Vampire Slayer and the Great Puppet Theater appeared. It is exactly what it sounds like. Here again, when Pinocchio is teamed up with the other puppets and treats them like family, he is still a puppet rather than a human being. The puppets, including Harlequin and Punchinello and Rose, are all stock figures from a form of Italian theater called commedia dell’arte. This has descendants throughout English theater traditions as well. Punchinello, Pulcinella or Punch is one of the main players of the Punch and Judy puppet show. British pantomimes of the 18th and 19th centuries often involved harlequinades, where characters transformed into the clowns Harlequin and Columbine for a dance. The multi-colored Harlequin was mute and carried a magic wand. Peter Pan almost included a harlequinade. Harlequin comes from the Italian Arlecchino. It may also have roots in Hellequin, a name for a leader of the terrifying Wild Hunt, or the German Erlkönig (Elf King). Further back, it may derive from a mythic figure known as Herla, who in turn is related to the Norse god Woden.

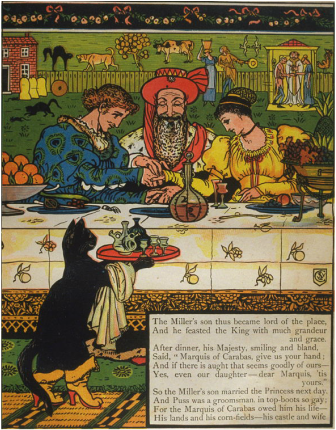

The Harlequin clown design also inspired DC Comics' multi-colored villain Harley Quinn. Perrault's "Puss in Boots" begins with a poor miller's son, alone in the world except for a pet cat. Things look bleak, until the cat speaks up. It has a plan to put the boy on a path straight up the social ladder, turning him from a beggar to the future king.

This is accomplished by a whole lot of lying. When the cat first introduces his master to the king and his daughter, he dubs him the Marquis of Carabas. The name is mentioned again and again throughout the story, and becomes the moniker by which the character is always referred. We never learn his real name. So what is Carabas? It's likely just a nonsense word created by Perrault. The cat makes up a title out of whole-cloth and gradually adds a princess and a castle to back it up. Carabas is not a real place. It's not supposed to be. In The Great Fairy Tale Tradition, Jack Zipes suggests that Perrault could have taken inspiration from stories of a fool in Alexandria named Carabas, who people mocked by treating like a king, or the Turkish word "Carabag" for a summer vacation spot in the mountains. A carabas is also a French term for a cage-like carriage, but the earliest mention I find of it is from 1874, well after Perrault, and it may derive from the Puss in Boots story. There are a few similar words in French. "Car" is a dialect word from Picardy meaning something along the lines of "that's why." "Caraba" is cashew nut oil. However, like the previous examples, these words have no obvious connection to Perrault's story. There are many versions of this tale, and some include similar aliases. A Swedish version has the Princess of Cattenburg, which is clearly Cat Town. Similarly, there's the Earl of Cattenborough in Joseph Jacobs' European Fairy Tales. It's unclear where exactly Jacobs got this story. The characters' names (Charles, Sam, and John) are all very English. He may have drawn elements from different variants of the Puss tale. He specifically mentions the Princess of Cattenburg, so he may have gotten the name here. Italian versions are Don Joseph Pear (derived from the pear tree that he owns) and Count Piro (which I believe also derives from pears in the story). Other Italian versions have the cat or fox helper rename its master Caglioso or Gagliuso, a name meaning youth. Actually, in quite a few of these versions, the animal helper is female. Perrault made the character male. Sometimes it's explained as a magical cat or an enchanted princess, but Perrault's cat just happens to be able to talk. SOURCES

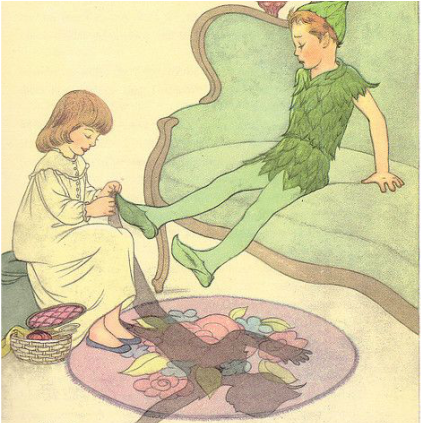

One of the most memorable scenes from Peter Pan is his first meeting with Wendy, where he loses his shadow and she sews it back on for him.

In the book, the shadow is pulled off when Nana catches it and the closing window severs it. It's treated like a physical object; it's "quite an ordinary shadow" and Mrs. Darling rolls it and puts it in a drawer. This fits with the book's whimsical tone, particularly the scene where she first attempts to hang it outside, only to see that it "looked so like the washing and lowered the whole tone of the house." In the Disney adaptation and the later 2003 adaptation, Peter's shadow is alive. It is a mischievous, active creature that Peter has to chase and catch. This is clearly a choice to make the scene more exciting for the medium of film. Upon being reattached, it goes back to normal and is never mentioned again. In the show Once Upon a Time, the Shadow is an demonic being that serves Peter Pan. In Peter and the Shadow Thieves, a children's sci-fi novel by Dave Barry and Ridley Pearson, where a being called Lord Ombra enslaves people by stealing their shadows. However, these more recent adaptations - which seem to draw more on the film versions with the living shadow - may miss the point behind Barrie's reasoning. Peter's shadow is what first draws him to Wendy. His origin story is that he left his home while the window was open. He returned returned to find that the window was shut and his mother had forgotten him. His encounter with Wendy, a new mother figure, repeats these elements in reverse. On his first visit, the closing window traps his shadow. When he returns to retrieve it, he is able to enter the house and spend time with Wendy. They are parted when he forgets her, and at this point she becomes a mother in the biological sense. There are plenty of literary references to the shadow becoming separated from the body. In The Wonderful Story of Peter Schlemihl, published in 1814 to general popularity, a man sells his shadow to the devil only to find that he is now shunned by society. In Hans Christian Andersen's "The Shadow," when a man's shadow is detached, it takes on a life of its own and eventually usurps his identity. In Oscar Wilde's "The Fisherman and His Soul," which reads like a response to both "The Shadow" and "The Little Mermaid," the shadow is the body of the soul. In Jewish lore, demons are believed to have no shadows. The shadow is an extension of oneself, symbolic of the soul, and without one, a person is lacking or not human. The opening chapters of Peter Pan have the only mention of shadows in the book. However, in the "Fairy Notes" containing Barrie's ideas, shadows show up multiple times. Note 210 reads, "Shadow of girl--P expected to find it cold--it's warm! Then she's not dead, &c." 206 mentions the idea that a warm shadow indicates that the owner is healthy, but the shadow's limp indicates that the owner has hurt her foot. This lends itself to the idea that the shadow is the double of the body and can indicate whether the soul still resides there. Barrie also considered using shadows as psychopomps. In the final version, Peter Pan is briefly mentioned as a psychopomp: "when children died he went part of the way with them, so that they should not be frightened." Note 95 says, "Girl suffering from want of her shadow - shadow also suffers, dwindles, &c," and Note 97, "Suppose you cd hurt Peter by hurting his shadow, &c, (as in Indian fairytale)." So Barrie took some inspiration from folklore and other literature. Note 99: "shadow is quivering {therefore} original is suffering somewhere." James Frazer's The Golden Bough (1922) explains how the shadow is viewed as a kind of voodoo doll; the same in the "Indian fairytale" Barrie mentions. Someone could hurt Peter by hurting his shadow. This explains his urgency in regaining it. [Edit 7/10/21: The "Indian fairytale" may be a legend referred to in The Golden Bough. In a section about superstitions that shadows are vulnerable, there is this : “After Sankara had destroyed the Buddhists in India, it is said that he journeyed to Nepaul, where he had some difference of opinion with the Grand Lama. To prove his supernatural powers, he soared into the air. But as he mounted up the Grand Lama, perceiving his shadow swaying and wavering on the ground, struck his knife into it and down fell Sankara and broke his neck.” Note that Sankara is flying like Peter Pan when he meets his demise. Another version, however, does not give the same implication that the knife causes Sankara to fall.] On another note: Barrie's fairies are creatures of light. The nocturnal fairies in Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens are "bewilderingly bright." Upon her introduction in Peter Pan, we learn that Tinker Bell's light "was not really a light; it made this light by flashing about so quickly," but when she lies dying, "her light was growing fainter; and he knew that if it went out she would be no more." Onstage, she was portrayed by shining a light. So these otherworldly beings are creatures of light. In folklore, fairies were connected to the souls of the dead and their realm to the underworld. In contrast to these glowing beings, the dark shadow identifies Peter as both a living being and someone with a soul. Peter is a psychopomp himself, only on the verge of being human. He tells Hook that he is "a little bird that has broken out of the egg," hearkening back to Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, where human babies are originally birds and Peter learns to fly from birds. But he still has a shadow, and this mark of humanity is the thing that leads him briefly away from the otherworldly realm of death and back to a family. In the end, he leaves that family, but continues a cycle of return where he takes Wendy's descendants one by one to Neverland. Neverland is an indulgence of childhood, the manifestation of the children's imagination. Their games and daydreams shape it; Wendy's imaginary pet wolf lives there. Even when they live there, their food is make-believe. Actually, this book presents kind of a horrible picture of children. They are innocent, but also heartless and don't care about anything. Arrogant, self-absorbed Peter is the most obvious example, but the Darling children abandon their parents without a second thought. It's Wendy's growing maturity that causes them to go home. SOURCES

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed