|

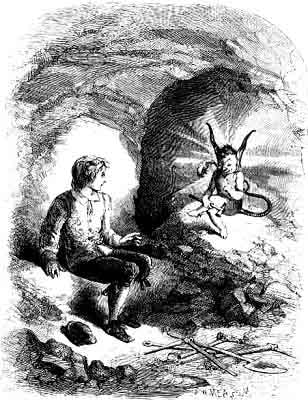

Ever since Walt Disney's Peter Pan came out in 1953, Tinker Bell has been a trademark mascot of the company, and an instantly familiar icon. The little pixie even got her own line of books and movies. However, in the original play and book by J. M. Barrie, she is simply a fairy. Disney changed her to a pixie and her fairy dust to pixie dust, permanently altering the language that people used for Tinker Bell. Why was this choice made? The Development of Disney's Tinker Bell Walt Disney began planning an animated adaptation of Peter Pan as early as 1935, and originally wanted it to be his next animated feature after Snow White. He obtained the rights in 1939, but various delays meant that it ultimately didn't get going until the late 40s. Tinker Bell's design followed on the heels of the Blue Fairy in Pinocchio and the tiny, glitter-strewing fairies in the Nutcracker Suite of Fantasia - both released in 1940. (Johnson 38-45) In the 1953 animated film, the word "fairy" is never used. On the other hand, "pixie" and "fairy" are used interchangeably in Disney's other works, such as the 2002 sequel Return to Neverland and the Disney Fairies spinoffs (which take place in Pixie Hollow). In one program, Walt Disney himself shook a "pixie bell" to summon Tinker Bell, but then remarked that "a little sprinkling of Tinker Bell's fairy dust can make you fly." (The Making of Peter Pan) Margaret Kerry, the reference model for Tinker Bell, remembered getting a call saying, "You’re up for a role of a three-and-a-half-inch fairy who doesn’t talk." (Kerry 177) In contrast, animator Marc Davis explained, "We knew we wanted [Tink] to be a pixie" (Johnson 108), and model Ginni Davis recalled being told in 1951 the character was a pixie (110), but it's unclear when these interviews took place. Either way, the terminology of "pixie" was evidently in place from almost the beginning. In early discarded storyboards, the movie started with a brunette Tinker Bell visiting Mermaid Lagoon seeking Peter Pan. A mermaid remarks, "My, but aren’t we the jealous little pixie-wixie!" (Johnson 95) Another storyboard has a "pixie" laughing at Nana the dog. Pixies in Folklore Let's talk about what pixies were, historically. “Pixie” is the term for fairy in Devon and Cornwall and may come from the same root as "pooka" and "Puck." The oldest known recording of the word was in the 16th century, in Nicholas Udal’s translation of Erasmus of Rotterdam’s Apophthegmata: “I shall be ready at thine elbow to plaie the part of Hobgoblin or Collepixie.” (This seems to have been a flowery detail added by Udal.) Pixies continued to appear in literature, for instance in Coleridge's poem "Songs of the Pixies." However, their local folklore became popular thanks to the English folklorist Anna Eliza Bray, starting with her A Description of the Part of Devonshire Bordering on the Tamar and the Tavy (1836). Although she recorded the traditions, she also shaped them for Victorian readers, particularly in her children's book A Peep at the Pixies (1854). Bray standardized the spelling as “pixie,” rather than pigsie or piskey or the many other variants floating around. While Bray states that "pixies are certainly a distinct race from the fairies," this is because they are the souls of unbaptized infants. In other ways, however, they are pretty much a synonym for fairies. They often starred in brownie-like tales where they completed housework or worked on farms. Like will-o'-the-wisps, they led people astray, thus the saying "pixy-led." They were known for their laughter, thus the existence of various sayings like "to laugh like a pixy." Bray described them as "tiny elves," fond of the wilderness and of dancing in circles, who could change their shape to be either beautiful or ugly. The one constant was that they always wore green. If you look at the pixies in A Peep at the Pixies, the name is used for a wide range of different fairylike beings, from the satyr-like Gathon to the ghostly water spirit Fontina. Another collector wrote in 1853 that not only could the Dartmoor pixies appear as “sprites of the smallest imaginable size", but they could look like large bundles of rags! (English forests and forest trees, historical, legendary, and descriptive.) Due to the new spotlight during the Victorian era, pixies began developing alongside fairies. They were depicted with the same pointy ears and sometimes wings. For instance, Mr. O'Malley was a stout, winged, troublesome pixie in Crockett Johnson's comic strip Barnaby, beginning in 1941. As they became popular, pixies were more often sharply separated from fairies. Ruth Tongue wrote in Somerset Folk Lore (1965): "The Pixies are a more prosaic type of creatures than the fairies... They are red-headed, with pointed ears, short faces and turned-up noses, often cross-eyed" (p. 113). She also stated that the pixies went to war with the fairies and drove them out of Somerset (112). Because this is Tongue, I'm side-eyeing it hard. I do think it bears noting that Tongue's pixies have the same red hair and pointed ears as Disney's Peter Pan, although make of that what you will. Pixies in Peter Pan I'm fairly sure J. M. Barrie never used the word "pixie" in any of his writing. He was working with the stuff of Victorian and Edwardian children's fantasy, and was inspired by works like the 1901 pantomime Bluebell in Fairyland. Pixies probably didn't even enter into it for him. However, readers and commenters sometimes used the term to describe Peter Pan. In 1923, a book review of Daniel O'Connor's The Peter Pan Picture Book stated that the illustrations were "full of a pixie liveliness specially adapted to the spirit of the tale." (The Bookman, Volume 65)

A poem in a 1937 issue of Punch wrote about wishing to be "the Pixie type... A-laughing in the sun," "a Tinkerbell," "a Never-Never girl, a sort of female Peter Pan," or "an elfin childish lass." One writer, describing Professor William Lyon Phelps, called him "over-enthusiastic about ephemeral bits of cleverness, about all the pixie descendants of Peter Pan." (Essay Annual, 1940) However, perhaps most relevant was the American actress Maude Adams. Sometime around 1909-1911, a young Walt and his brother Roy watched the play 'Peter Pan', starring Adams. In the original UK productions, Peter Pan wore a reddish tunic. Adams was the first to wear the feathered cap and the leafy green tunic with a “Peter Pan collar." The Peter Pan collar would become popular in women’s fashion. Illustrator Mabel Lucie Attwell, in 1921, drew Peter with a similar ensemble - the pointed cap looked a little like Adams', a little like a helmet, a little like the pointed acorn caps often given to fairies in illustrations. And of course, Disney's Peter Pan design was directly influenced by Maude Adams' look. Adams’ feathered cap may have been a “pixie hat,” a name given to a wide variety of small pointed hats popular from around the 1930s through 1960s. They were mainly worn by women and girls. Although the hat may not have had that name when Adams first wore it, the term would have been familiar at least by the 1940s. And one writer wrote in 1938 that Adams had “a pixie quality to her personality that made her ‘Peter Pan’ believable and understandable.” It’s possible that the word “pixie,” applied to Adams’ Peter Pan, could have influenced how Disney described Tink. However, it's intriguing that the term "pixie" was first used for either Peter Pan the story or Peter Pan the character - not for Tinker Bell. Disney may have liked the sound of "pixie." Or he may have liked that it implied a smallness and a mischievous, childlike nature, in contrast to the more mature and graceful Blue Fairy. Look at those early-1900s references to liveliness and laughing. There are also some pixie associations that seem very fitting for Tinker Bell: they do housework and she is a tinker, they lead people astray and she glows like a will-o'-the-wisp. But again, it's important to remember that all of this is because pixie is a dialect term, a synonym, for fairy. They were not originally a separate species, as Ruth Tongue would have it. All the same things that associate Tinker Bell with pixies also associate her with fairies in general. Sources

Other Posts

3 Comments

Pillywiggins spurred a lot of my fairylore research. They got me interested in the development of tiny winged fairies and how folklore is evolving in modern culture. I once wrote that I don’t mind using the word “pillywiggin” for the modern flower fairy, but since then, I've grown frustrated by the term. Nearly all of the usual descriptions (appearance, behavior, etc.) are later add-ons which only muddy the question of origins. Recently, I went back to the original source: the 1977 book A Field Guide to the Little People, by American author Nancy Arrowsmith. I now think I was focusing on the wrong details. There may be an alternate clue buried in the text.

First off: I am throwing out any pillywiggin sources published after 1977. They all ultimately lead back to the Field Guide. At one point I guessed that a 1986 "story request" issue of My Little Pony might hold clues, but after more research, I don't think readers had any input. It was just a dedication. Pillywiggins were supposed to be from Dorset, and have appeared in a handful of 21st-century literary works (the Dark Dorset books by Robert Newland, 2002-2006, and the "Sting in the Tale" storytelling festival in East Dorset, 2014-2015). And I did hear from one commenter whose grandmother from Dorset had spoken of "pesky" pillywiggins. However, there are a couple of things that give me pause. 1) Dorset folklorist Jeremy Harte nodded indirectly to pillywiggins in a 2018 article only to say that he had not encountered such stories in tradition (Magical Folk: British and Irish Fairies - 500 AD to the Present). This is the closest we have ever come to a discussion of pillywiggins in an academic work: an expert saying that they "do not appear in any known sources." 2) The existing Dorset sources are all from the 21st century. 2002 was 25 years after pillywiggins were first publicized. Now it's been 44 years. With no independent primary sources, that leaves the Field Guide as the only possible lead. A Field Guide to the Little People was Arrowsmith's only book on fairies, but with its whimsical and accessible descriptions, it became a cult classic and was reprinted and translated multiple times. Arrowsmith's foreword to the 2009 edition talks about her research process. At the Bavarian National Library she read through books on myth and superstition, taking notes in notebooks and on thousands of index cards (which sounds honestly really cool). To be clear, I don't want to undermine the author; my goal is simply to find out more about this one specific fairy. So far, I have only encountered one other point where I couldn't initially find a source: a description of Italian fairies called gianes (pp. 169-171). However, then I discovered that Gino Bottiglioni, one of the sources listed in the bibliography, wrote of gianas, a slightly different plural. I thought pillywiggins could be a similar case. The section "English Fairies" (pp. 159-162) includes this brief description: "The popularized Dorset Fairies, Pillywiggins, are tiny flower spirits.” All of the other creatures here (hyter sprites, Tiddy Ones, vairies, farisees, etc.) are easily traceable to older works. Nearly all of them appear in Katharine Briggs’ comprehensive overview of British fairylore, The Fairies in Tradition and Literature (1967). That book was a major source for this section, judging by the details (for instance, the unusual variation "Tiddy Ones" rather than Tiddy folk or people). It followed up from Briggs’ previous book The Anatomy of Puck (1959), which focused on fairies in Elizabethan and Jacobean literature. Both of these works are included in the Field Guide's bibliography. In this post, I'm going to go slowly through the earliest known definition of pillywiggins, comparing it to the sources in the Field Guide's bibliography. For full disclosure, I have gone through the bibliography except for some out-of-print German and Italian books not available in the U.S. Also, there are books where I was not able to obtain the exact edition used, and had to go with an older or newer version. POPULARIZED DORSET FAIRIES The sources hold very little Dorset fairylore. In Keightley's Fairy Mythology and Brand’s Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain, the Dorsetshire pexy or colepexy haunts the woods as a threatening bogeyman for naughty children. Fossils are called the colepexy's head or fingers. The Anatomy of Puck briefly mentions John Walsh, an accused witch who said he'd met with the fairies (or "feries") of the Dorset hills. The Folk-Lore Journal volumes 1-7 were all counted as sources. The Volume 6 article “Dorset Folk-Lore” mentions a superstition that wicked fairies will enter homes through the chimney unless warded off using a bull's heart. None of these are associated with flowers, and it seems like a stretch to call them "popularized." These are stories of severed body parts, witchcraft and malevolent spirits. PILLYWIGGINS There are similar fairy names such as Pigwiggen, Skillywidden, and the German pilwiz. However, none of these quite fit the details given in the Field Guide for pillywiggins. Pigwiggen (also spelled Pigwiggin) is the closest. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the word "Pigwiggen" to at least 1594. From early on, the word had shades of a cutesy endearment or belittling insult. I believe it originated as a rhyming nickname for a young pig. Similar terms like piggy-whidden or piggen-riggen have survived. It doesn’t suggest the same level of miniaturization as the Mustardseed and Moth of A Midsummer Night's Dream, or the Penny and Cricket of the 1600 play The Maydes Metamorphosis, but does imply littleness if you envision a runt piglet. And traditional fairies could be small without being bug-sized; in fact, the popularity of this extreme tininess was fairly new around 1600. Most famously, Pigwiggen is the name of a character in Michael Drayton's 1627 poem "Nymphidia": a fairy knight who holds a tryst with Queen Mab inside a cowslip flower. He rides an earwig and has a fish scale for armor, a beetle’s head for a helmet, a cockle-shell for a shield and a hornet’s sting for a rapier. His squire is Tom Thumb, also closely associated with flower fairies and a byword for "miniature." There may have been an earlier fairy with the name. “Lady Piggwiggin, th'only snoutfaire of the fairies” appeared in "The Masque of the Twelve Months," which some scholars have dated around 1610-1619. This somewhat bawdy character is nicknamed "Pig." "Snoutfaire" means "fair-faced" or "comely" but can double as an insult; here it was probably a pun on a pig's snout. She is compared in size to a mouse (much larger than the microscopic Sir Pigwiggen), and disguises herself as a glowworm, reminding me of the much later Tinker Bell. Nymphidia's Pigwiggen would be considered a flower fairy, and was absolutely popularized. The word was already the subject of many spelling changes and clerical errors. Arrowsmith would have encountered references in works such as the following:

With this wealth of alternate spellings, it seems very possible that pillywiggin derived from Pigwiggen. Maybe we have another portmanteau like Perriwiggin on our hands: it might have been combined with Skillywidden, which also appeared in several of the sources. (The Anatomy of Puck includes the story of the tiny fairy found in the furze, and compares Skillywidden to the helpless Tom Thumb - who was elsewhere connected to the "Pigwiggen type". Eileen Molony's Folk Tales of the West retells the story with "skillywiddon" as the name of a fairy race.) On the other hand, none of this has nothing to do with Dorset. TINY FLOWER SPIRITS The pillywiggins are called "flower spirits." This phrase appears verbatim in The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, when Briggs argued that William Shakespeare and Michael Drayton relied on a West Midlands tradition of "small and beautiful" fairies who were "nearer to being flower spirits than spirits of the dead." (p. 109) Briggs repeatedly mentioned "flower fairies" or "small, flower-loving fairies" in The Fairies in Tradition and Literature and The Anatomy of Puck (and other books, but these were the two in the Field Guide's bibliography). Anatomy, especially, explores the late 16th/early 17th-century literature where tiny flower fairies became a fad. I always approached this as if there was one issue: the pillywiggins. I took the mention of Dorset at face value. But maybe "flower spirits," rather than "Dorset," are the key to the puzzle. Here's my amended theory. The original complete description reads: "The popularized Dorset Fairies, Pillywiggins, are tiny flower spirits." There are a couple of things that "Dorset" could mean. Option 1: "The popularized Drayton Fairies, Pigwiggins, are tiny flower spirits.” This is supported by the common thread of "flower spirits" in the writings of both Arrowsmith and Briggs. If it was originally “Drayton fairies,” there are some possible parallels in the “Folk-Lore of Drayton” article (“Drayton's fairies are true Teutonic tinies”), The Anatomy of Puck (“Drayton’s fairies are smaller even than the elves who crept into an acorn cup,” p. 58) and The Fairies of Tradition and Literature (“the small fairies of Shakespeare and Lyly and Drayton were imported into the fashionable world from the country,” p. 221). Also, Brand's Observations quotes Drayton's poem Polyolbion when discussing the Dorsetshire colepexy. However, Drayton’s name does appear correctly at the beginning of the “English Fairies” section: "The word ‘fairy’ has been so often misused (especially by Poets such as Spenser and Drayton) that it is very misleading to employ it as a scientific designation for a particular species of elf." (Edmund Spenser and Michael Drayton both wrote famous fairy poems, but Spenser’s “Faery Queen” was the sort of mythic romance that Drayton’s “Nymphidia” parodied. Both were criticized on occasion.) Option 2: "The popularized Durham Fairies, Piggwiggins, are tiny flower spirits.” The English Dialect Dictionary's definition of "piggwiggan" or "Peggy Wigan" (notice the spelling) lists the location as "Dur.," an abbreviation of Durham. This could have been misread as "Dor.," or Dorset. This factoid originally came from the Denham Tracts; the collector Michael Aislabie Denham was a Durham native. It seems like "Peggy Wiggan" was the term actually used, since Denham specifies that this is the vulgo or common pronunciation. When someone suffered a bad fall, it was said they had got or caught Peggy Wiggan. This sounds like a normal woman's name, especially in context with the many other bewildering proverbs in Denham’s list, like “Rather better than common, like Nanny Helmsey’s pie.” Many of them seem like in-jokes specifically to tease local townspeople, like one about a man named David Pearse who mispronounced the word "genuine." (Denham 65, 87) It's unclear whether anyone actually used "piggwiggan," or if there was any fairy association before Denham suggested it. However, it's possible that someone, having read Katharine Briggs' argument that Drayton took his tiny flower fairies from local folklore, could spot the out-of-context line in the English Dialect Dictionary and theorize that this was the source. Conclusion When I first visited this subject, I thought it was a possibility that Pillywiggin was a misspelling of Pigwiggen. However, the mention of Dorset was always a stumbling block for me. If “Dorset” was meant to be “Drayton" or "Durham," then it makes much more sense. “Pillywiggin” is a corruption of Pigwiggen just like “Perriwiggin” and “Pigwidgeon." All other details (like their exact relationship with flowers, and their wings or lack thereof) were added by modern writers of fiction. And the name totally means “piglet.” Others may disagree, or may have other suggestions. Comment below and share your thoughts! Sources:

Other Blog Posts |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed