|

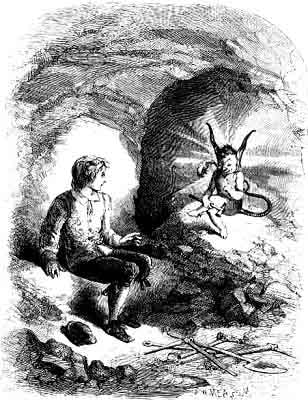

Ever since Walt Disney's Peter Pan came out in 1953, Tinker Bell has been a trademark mascot of the company, and an instantly familiar icon. The little pixie even got her own line of books and movies. However, in the original play and book by J. M. Barrie, she is simply a fairy. Disney changed her to a pixie and her fairy dust to pixie dust, permanently altering the language that people used for Tinker Bell. Why was this choice made? The Development of Disney's Tinker Bell Walt Disney began planning an animated adaptation of Peter Pan as early as 1935, and originally wanted it to be his next animated feature after Snow White. He obtained the rights in 1939, but various delays meant that it ultimately didn't get going until the late 40s. Tinker Bell's design followed on the heels of the Blue Fairy in Pinocchio and the tiny, glitter-strewing fairies in the Nutcracker Suite of Fantasia - both released in 1940. (Johnson 38-45) In the 1953 animated film, the word "fairy" is never used. On the other hand, "pixie" and "fairy" are used interchangeably in Disney's other works, such as the 2002 sequel Return to Neverland and the Disney Fairies spinoffs (which take place in Pixie Hollow). In one program, Walt Disney himself shook a "pixie bell" to summon Tinker Bell, but then remarked that "a little sprinkling of Tinker Bell's fairy dust can make you fly." (The Making of Peter Pan) Margaret Kerry, the reference model for Tinker Bell, remembered getting a call saying, "You’re up for a role of a three-and-a-half-inch fairy who doesn’t talk." (Kerry 177) In contrast, animator Marc Davis explained, "We knew we wanted [Tink] to be a pixie" (Johnson 108), and model Ginni Davis recalled being told in 1951 the character was a pixie (110), but it's unclear when these interviews took place. Either way, the terminology of "pixie" was evidently in place from almost the beginning. In early discarded storyboards, the movie started with a brunette Tinker Bell visiting Mermaid Lagoon seeking Peter Pan. A mermaid remarks, "My, but aren’t we the jealous little pixie-wixie!" (Johnson 95) Another storyboard has a "pixie" laughing at Nana the dog. Pixies in Folklore Let's talk about what pixies were, historically. “Pixie” is the term for fairy in Devon and Cornwall and may come from the same root as "pooka" and "Puck." The oldest known recording of the word was in the 16th century, in Nicholas Udal’s translation of Erasmus of Rotterdam’s Apophthegmata: “I shall be ready at thine elbow to plaie the part of Hobgoblin or Collepixie.” (This seems to have been a flowery detail added by Udal.) Pixies continued to appear in literature, for instance in Coleridge's poem "Songs of the Pixies." However, their local folklore became popular thanks to the English folklorist Anna Eliza Bray, starting with her A Description of the Part of Devonshire Bordering on the Tamar and the Tavy (1836). Although she recorded the traditions, she also shaped them for Victorian readers, particularly in her children's book A Peep at the Pixies (1854). Bray standardized the spelling as “pixie,” rather than pigsie or piskey or the many other variants floating around. While Bray states that "pixies are certainly a distinct race from the fairies," this is because they are the souls of unbaptized infants. In other ways, however, they are pretty much a synonym for fairies. They often starred in brownie-like tales where they completed housework or worked on farms. Like will-o'-the-wisps, they led people astray, thus the saying "pixy-led." They were known for their laughter, thus the existence of various sayings like "to laugh like a pixy." Bray described them as "tiny elves," fond of the wilderness and of dancing in circles, who could change their shape to be either beautiful or ugly. The one constant was that they always wore green. If you look at the pixies in A Peep at the Pixies, the name is used for a wide range of different fairylike beings, from the satyr-like Gathon to the ghostly water spirit Fontina. Another collector wrote in 1853 that not only could the Dartmoor pixies appear as “sprites of the smallest imaginable size", but they could look like large bundles of rags! (English forests and forest trees, historical, legendary, and descriptive.) Due to the new spotlight during the Victorian era, pixies began developing alongside fairies. They were depicted with the same pointy ears and sometimes wings. For instance, Mr. O'Malley was a stout, winged, troublesome pixie in Crockett Johnson's comic strip Barnaby, beginning in 1941. As they became popular, pixies were more often sharply separated from fairies. Ruth Tongue wrote in Somerset Folk Lore (1965): "The Pixies are a more prosaic type of creatures than the fairies... They are red-headed, with pointed ears, short faces and turned-up noses, often cross-eyed" (p. 113). She also stated that the pixies went to war with the fairies and drove them out of Somerset (112). Because this is Tongue, I'm side-eyeing it hard. I do think it bears noting that Tongue's pixies have the same red hair and pointed ears as Disney's Peter Pan, although make of that what you will. Pixies in Peter Pan I'm fairly sure J. M. Barrie never used the word "pixie" in any of his writing. He was working with the stuff of Victorian and Edwardian children's fantasy, and was inspired by works like the 1901 pantomime Bluebell in Fairyland. Pixies probably didn't even enter into it for him. However, readers and commenters sometimes used the term to describe Peter Pan. In 1923, a book review of Daniel O'Connor's The Peter Pan Picture Book stated that the illustrations were "full of a pixie liveliness specially adapted to the spirit of the tale." (The Bookman, Volume 65)

A poem in a 1937 issue of Punch wrote about wishing to be "the Pixie type... A-laughing in the sun," "a Tinkerbell," "a Never-Never girl, a sort of female Peter Pan," or "an elfin childish lass." One writer, describing Professor William Lyon Phelps, called him "over-enthusiastic about ephemeral bits of cleverness, about all the pixie descendants of Peter Pan." (Essay Annual, 1940) However, perhaps most relevant was the American actress Maude Adams. Sometime around 1909-1911, a young Walt and his brother Roy watched the play 'Peter Pan', starring Adams. In the original UK productions, Peter Pan wore a reddish tunic. Adams was the first to wear the feathered cap and the leafy green tunic with a “Peter Pan collar." The Peter Pan collar would become popular in women’s fashion. Illustrator Mabel Lucie Attwell, in 1921, drew Peter with a similar ensemble - the pointed cap looked a little like Adams', a little like a helmet, a little like the pointed acorn caps often given to fairies in illustrations. And of course, Disney's Peter Pan design was directly influenced by Maude Adams' look. Adams’ feathered cap may have been a “pixie hat,” a name given to a wide variety of small pointed hats popular from around the 1930s through 1960s. They were mainly worn by women and girls. Although the hat may not have had that name when Adams first wore it, the term would have been familiar at least by the 1940s. And one writer wrote in 1938 that Adams had “a pixie quality to her personality that made her ‘Peter Pan’ believable and understandable.” It’s possible that the word “pixie,” applied to Adams’ Peter Pan, could have influenced how Disney described Tink. However, it's intriguing that the term "pixie" was first used for either Peter Pan the story or Peter Pan the character - not for Tinker Bell. Disney may have liked the sound of "pixie." Or he may have liked that it implied a smallness and a mischievous, childlike nature, in contrast to the more mature and graceful Blue Fairy. Look at those early-1900s references to liveliness and laughing. There are also some pixie associations that seem very fitting for Tinker Bell: they do housework and she is a tinker, they lead people astray and she glows like a will-o'-the-wisp. But again, it's important to remember that all of this is because pixie is a dialect term, a synonym, for fairy. They were not originally a separate species, as Ruth Tongue would have it. All the same things that associate Tinker Bell with pixies also associate her with fairies in general. Sources

Other Posts Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

3 Comments

Liam

10/10/2021 06:14:17 pm

I always heard that pixie legends were descended from mythologized descriptions of the Picts of Scotland. Is that false?

Reply

Writing in Margins

10/10/2021 07:49:38 pm

That's one of the theories, but I'm skeptical. Although the Picts were mythologized in Scotland, there's not much evidence to connect them to pixies. The distance from Scotland to Cornwall with its very localized pixie tradition also makes this seem like a stretch. I recommend Gillian Edwards' book "Hobgoblin and Sweet Puck: Fairy Names and Natures."

Reply

thinkerbellHater8

3/27/2023 01:35:19 pm

thank you for the inspo. Takin much credit. LOVING THIS!!! very insightful and prett y academic too. I'm obsesssssssssed with your take on tinky

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed