|

Petrus Gonsalvus, or Pedro Gonzalez, lived at the court of the French king Henri II. Gonsalvus had a condition which today would be diagnosed as hypertrichosis, causing excessive hair growth; his face was almost completely covered in hair. People who met him would have thought immediately of the wild men of medieval legend. Around age ten, he was brought to court as a kind of curiosity and pet, much like other people with physical differences at the time. This is where he grew up, was educated, and eventually married a woman named Catherine. Most of their children shared Gonsalvus’s diagnosis; so did some of their grandchildren. Their medical studies and portraits still survive today. But was there more than a scientific interest to Gonsalvus's story? Were he and his wife the original inspiration for "Beauty and the Beast?"

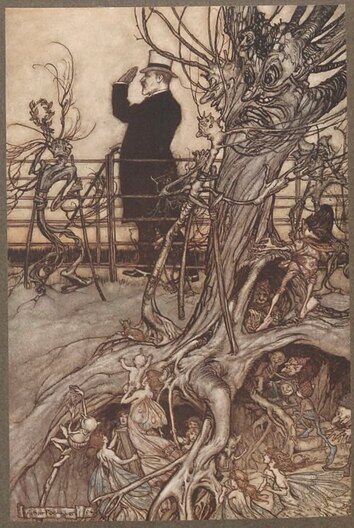

I have never seen Gonsalvus mentioned in any analysis of the fairy tale, which is well-known to be inspired by an ancient storytelling tradition. That's not a great sign. But the theory has been shared around a fair amount and has some traction, so it deserves a look. The most well-known English work about Gonsalvus is probably a Smithsonian Channel documentary titled "The Real Beauty and the Beast”, directed by Julian Pölsler (2014). As seen by the title, it strongly promoted the fairy tale connection. It is no longer available on any streaming services, but based on the various reviews and summaries I’ve found, it runs something like this. Pedro is brought to Henri II’s court as a feral child: kept in a cage, fed raw meat, and unable to say anything but his name. Henri II bestows an education on him, translating his name into Latin as Petrus. Petrus thrives in his new life, but Henri II’s wife, the villainous Catherine de' Medici, designs a sadistic experiment to see whether Petrus’s children will also be hairy. She marries him to one of her servant girls, also named Catherine. The bride knows nothing about her groom, and faints when she sees him for the first time at the altar. Their union ends up being a happy one as she discovers Petrus is a kind and gentle man. Still, their happiness is marred, as their children who inherit Petrus’s condition are taken away and gifted to various nobles, and even though Petrus and Catherine ultimately settle down to a quiet life in Italy, the lack of burial records is interpreted to mean that Petrus is still seen as a beast and denied the Christian rites of burial. It’s a tragic Beauty and the Beast retelling complete with the moral of looking beyond appearances and plenty of memorable dramatic details (like Catherine "fainting at the altar.") This documentary seems to have been heavily fictionalized, and does not seem like a reliable source. (Incidentally, Beauty faints at the first sight of the Beast in the 1946 film La Belle et la Bête, although not in the fairy tale. So I wonder if the filmmakers actually drew from Beauty and the Beast stories to craft their depiction of Petrus and Catherine. As we'll see in a minute, there's no historical basis for details like Catherine fainting.) The Gonzalez family in historical record We can only get at the Gonzalez family’s story by piecing together brief and scattered sources. It’s hard to pin down dates, and English studies are especially scarce. Gonsalvus was known in life as "le Sauvage du Roi" (“the King’s Savage”) or, more personally, “Don Pedro.” His name appears under many different translations; it seems like he preferred Pedro, so that's what I'm going with. He was born in Tenerife in 1537, spoke Spanish, and was probably Guanche (the indigenous people of Tenerife, enslaved by the Spaniards during conquest). It may be that he was brought straight from Tenerife by slave traders. On the other hand, Alberto Quartapelle found another account from about the same time of a hirsute ten-year-old shown off throughout Spain by his father; given the rarity of the condition, it’s possible that this was Pedro, and that his own father showed him off and eventually gave or sold him to the French king. What is generally agreed on is that Henry II wanted to prove that a “savage” could be transformed into a gentleman. He arranged for Pedro to live like other noble children of court and receive a royal education. He chose important officials as Pedro’s tutors and caretakers. As he grew older, Pedro served at the king’s table, a small but still prestigious task with a salary and personal access to the monarch. After Henri II's death in 1559, his widow the regent Catherine de'Medici became Pedro’s main patron. She probably did either arrange his marriage or, at the very least, promise financial support (she arranged marriages for her court dwarfs). In Paris, in 1570, Pedro married Catherine Raffelin (spelled variously as Raphelin, Rafflin, Rophelin), the daughter of Anselme Raffelin (a textile merchant) and Catherine Pecan. As part of her dowry, Catherine Raffelin brought half of an apartment on Rue Saint-Victoir, where the couple moved. We don’t know what they may have thought of each other at first or what their first meeting was like. However, Pedro’s extensive education and wealthy lifestyle would presumably have been appealing to a potential wife. Portraits of Pedro and Catherine are reminiscent of Beauty and the Beast. And not only was Catherine a merchant’s daughter just like the Beauty of the fairy tale, but it seems she was considered a lovely woman. A portrait by Joris Hoefnagel (included at the top of this post), which shows Catherine resting a hand on her husband's shoulder, was accompanied by a segment written from Pedro’s point of view (possibly even by Pedro himself?) describing Catherine as “a wife of outstanding beauty” (Wiesner 153). Merry Wiesner lists their seven children as Maddalena, Paulo, Enrico, Francesca, Antonietta (“Tognina”), Orazio, and Ercole. All three girls plus Enrico and Orazio had hypertrichosis. Ercole apparently died in infancy, with records unclear whether he was hirsute. With baptismal records, Quartapelle places their births a few years earlier than Wiesner’s estimates and gives the initial four (in French) as Francoise, Perre (Pierre?), Henri, and Charlotte. Some children were recorded more than others, which means some may have died young; alternately, the children who didn’t inherit hypertrichosis were not recorded as much. During his years in Paris, Don Pedro studied at the University of Poitiers and became a professor of canon law. He was also in frequent contact with the king, being tasked with delivering his books. Important noblemen close to the royal family served as godfathers to the Gonzalez children. However, around the 1580s or 1590s, something happened. The family began traveling and showing up in the records of various European courts. This was also the period when many of the portraits and medical studies were done. We don't know exactly when they left, but the queen's will provided for her court dwarfs and not the Gonzalezes, which might indicate that they already had a new patron by then. It's not clear exactly why this happened, but in 1589 there were a couple of significant events: the death of Catherine de'Medici and the assassination of her son Henri III (Ghadessi p. 109-110). France was full of civil and religious unrest, Henri III's death sent people into a frenzy of joy, and it was probably not the best time to be an easily-recognizable favorite of the royal family. If the Gonzalezes hadn't already left, that would have been the time to get out. They ultimately entered the patronage of Duke Alessandro Farnese and settled at his court in Parma, Italy. The children with hypertrichosis lived similarly to their father, sent as gifts to the courts of Farnese relatives and friends. Despite this disturbing note, it does seem that the family kept in contact. Most or all of them eventually moved to the small village of Capodimonte. Their sons found wives there, and Orazio occasionally commuted from there to Rome, where he held a position in the Farnese court (Wiesner, 220). Pedro is thought to have died in Capodimonte around 1618, Catherine a few years later. There’s debate over how much agency the family members had, but Roberto Zapperi argues that their son Enrico used his position wisely and pulled strings with the Farneses to make this quiet retirement possible (Stockinger, 2004). So, a couple of notes on the information floating around from the Smithsonian documentary. First, it apparently painted Catherine de’Medici as a cruel woman who treated the Gonzalez family like a science experiment. In a completely opposite take, scholar Touba Ghadessi suggests a protectiveness, honor, and perhaps even fondness in her patronage of the family. I wonder if the truth is some mixture of the two; it wasn't necessarily black and white, and there could have been both fondness and rampant exploitation. Oddly enough, Catherine de' Medici had a little bit in common with the Gonzalezes. She, too, was foreign, and her enemies described her as monstrous. And the Gonzalezes ultimately settled in her homeland of Italy. As for the burial thing: the fact that we don't have burial records for Pedro doesn't really mean anything. The records are so spotty that it's not even clear what all of his kids' names were. Furthermore, we have baptismal and burial records for some of his children who shared his condition. I don't believe he was "denied a Christian burial" or anything like that. The inherent contradiction is seen in the fact that Pedro was married. However... it’s true that in spite of gaining some privileges - pursuing his studies, finding a wife, settling down in a quiet home - Pedro was never fully free. He was taken from his childhood home and possibly even shown off around Spain by his own father. He and his children lived their lives being othered and commodified by those around them, viewed as curiosities and entertainment. And societal attitudes towards him and his family show in the family portraits, where Gonsalvus and his children wear courtly dress but are juxtaposed against caves and wild scenes befitting animals. The fairy tale of "Beauty and the Beast" The story that we know today as “Beauty and the Beast” is not a folktale, but a literary fairy tale, originating with Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve’s Beauty and the Beast (1740). This was a fantasy novella following conventions of the time, full of vivid descriptions and convoluted subplots. It took clear inspiration from folktales of beastly bridegrooms. The earliest written examples of this tradition are “Cupid and Psyche” (Rome, 2nd century AD) and “The Enchanted Brahman's Son” (India, ~3rd-5th centuries AD). People in Pedro and Catherine's time might have read Straparola's "The Pig King" from the 1550s. Closer to home for Barbot, there was D'Aulnoy's "The Ram" (1697) and Bignon's "Princess Zeineb and the Leopard" (1712-1714). Because "Beauty and the Beast" is literary, created by a single author, it’s far more likely to contain specific references or traceable inspirations than an oral folktale would be. So, was Pedro Gonzalez one of Barbot's influences? Well… it's not clear if Barbot would have known who Gonzalez was. The family's personal history has only regained attention since the 20th century, with researchers like Italian historian Roberto Zapperi doing a lot of the work to piece together the details. The family’s legacy seems more associated with Austria than with France. Their portraits in Ambras Castle in modern-day Austria remained famous, even leading to the name "Ambras Syndrome" for a type of hypertrichosis. But an inventory of the Ambras Castle collection listed Gonzalez as “der rauch man zu Munichen”, or “the hirsute man from Munich,” because that’s where the portraits were painted (Hertel, 4). Meanwhile, in France: in 1569, author Marin Liberge could make reference to “the King’s Savage” expecting that his audience would know who he meant (Amples discours de ce qui c'est faict et passe au siege de Poictiers). But by the late 19th century, French researchers were absolutely baffled by this cryptic description, not connecting it to the portraits at all. One researcher in 1895 was on the right track with the idea that Don Pedro was some type of entertainer, but also noted that his memory simply isn’t well preserved in historical records, and questioned how well-known he actually was (Babinet 143-145). When Barbot was writing in 1740, a hundred and fifty years after Gonzalez's heyday in Paris, how well was he remembered? Did Barbot ever hear of the Ambras Castle collection? Even if she did, how much would she learn of Catherine - who was only in the portraits as Gonzalez's anonymous wife? In fact, Barbot’s novel features several vivid descriptions of the Beast, and he doesn't look anything like Pedro Gonzalez. He is covered in scales, with an elephant-like trunk. This Beast seems more influenced by stories of snake husbands - like the two oldest recorded versions of beastly bridegroom tales. Psyche fears that her husband is a serpent or dragon (although Cupid never actually appears this way in the story), and the Enchanted Brahman’s Son is a snake. With the lack of parallels and number of differences, it seems unlikely that Gonzalez inspired this. A few years later, Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont wrote a shorter, child-friendly adaptation of “Beauty and the Beast” which became pretty much the canon version. In her version, the Beast is barely described. This gave illustrators the freedom to imagine their own interpretations. You’ll find images of the Beast as an elephant, bear, wild boar, lion, or walrus. Depictions leaned more towards large, hairy beasts associated with strength and fearsomeness. In the era of adaptation and illustration, the Beast is more likely to be some kind of bipedal chimera. This leads up to the most iconic film portrayal: Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film La Belle et la Bête with its leonine Beast. The resemblance between the Gonzalez portraits and Cocteau’s Beast in his extravagant ruff and doublet is so striking that it seems likely the makeup artist, Hagop Arakelian, drew inspiration from Pedro Gonzalez (Hamburger, pp. 60-61). Similarly, Disney artist Don Hahn recalled the Gonzalez portraits as "one of many sources of inspiration" during early design stages for the 1991 animated film Beauty and the Beast (Burchard, 173). So, did the author of Beauty and the Beast take inspiration from Pedro Gonzalez and his wife Catherine? Probably not; there's nothing to indicate that she did, and a few things to point against it. But did later artists? Possibly! Fairy tales are archetypal, resonating with universal morals and fears. Trying to attribute a fairy tale to a real person's biography is dangerous ground. But sometimes real people do get adopted into storytelling tradition, and what's more, real events can have parallels to fairy tales. Sometimes, there really is a hairy nobleman who marries a merchant's beautiful daughter. We know very little about Pedro and Catherine Gonzalez; we don't know whether they had a romance for the ages. But their story is worth remembering, and I hope scholars are able to uncover more about them. SOURCES

Further Reading

1 Comment

A while ago, I spent several blog posts reviewing historical figures who have been put forward as the "real Snow White" - both of which turned out to be marketing campaigns with only the flimsiest of connections. Anastasia provides a look at something like the opposite. The real story of Anastasia Romanova is short, brutal and heartbreaking, but it’s been used as the basis for a fairy tale.

On July 17, 1918, the Russian imperial family was executed by Bolshevik revolutionaries. This included the Tsar Nicholas II, his wife the Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, and their children Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei, along with members of their entourage. Their executioners mutilated the bodies and buried them in the woods. Afterwards, the Bolsheviks announced Nicholas's death, but they covered up the deaths of his family and spread misinformation about them. This added fuel to the persistent idea that some might have survived. Numerous impostors appeared claiming to be surviving members of the imperial family who had escaped. The most famous, by far, was Anna Anderson. The Anna Anderson Timeline 1920: An unknown young woman is admitted to a mental hospital after a suicide attempt. Eventually, she begins claiming to be one of the Romanov princesses—initially Tatiana but then Anastasia. By 1922, she has come to the attention of Romanov supporters, friends and surviving relatives, and is using the name Anna (short for Anastasia). Some of the relatives denounce her as a fraud, but others embrace her. Despite her troubled and erratic behavior, and the fact that an investigation in 1927 points to her actually being a missing Polish factory worker named Franziska Schanzkowska, Anna becomes extremely famous. Supporters provide enough money for her to live comfortably. Adopting the surname Anderson, she's introduced to high society in America. Anderson’s story inspires numerous media adaptations, whether movies or stage or books. Some of these adaptations accept her claims; others draw more nuanced portraits that don’t settle on whether or not they believe her. 1928: The silent film Clothes Make the Woman, loosely inspired by Anna Anderson, depicts Princess Anastasia escaping the Bolsheviks with the help of a sympathetic revolutionary and coming to America. 1953: Marcelle Maurette writes a play called Anastasia, in which a team of conmen decide to use an amnesiac woman, "Anna," to fake the return of Princess Anastasia and swindle her grandmother, the Grand Duchess. But Anna might actually be Anastasia. The question never gets a definitive yes-or-no answer. In an ending twist, she falls in love and runs away to lead a normal life. 1956: Ingrid Bergman stars in Anastasia, a film adaptation of Maurette's play. The same year also sees a German film, The Story of Anastasia. 1979: An amateur sleuth discovers the mass grave of the Romanovs, although further investigation is impossible due to the Soviets. 1984: Anna Anderson dies of pneumonia in the U.S. 1991: Collapse of the Soviet Union. DNA analysis confirms that the bodies in the mass grave are those of the Romanovs. However, Alexei and one of the girls (either Maria or Anastasia) are unaccounted for. Tests of Anna Anderson's DNA prove that she was not a Romanov and strongly indicate that she was Franziska Schanzkowska. So after all the debate, all the bitter argument and broken relationships among supporters and opponents, “Anna” is finally proven a fraud . . . but the two missing bodies still leave room for the idea of a surviving Romanov. 1997: Don Bluth's animated film Anastasia loosely adapts the 1956 Ingrid Bergman movie (which, remember, was an adaptation of the 1953 play). This version is straightforwardly marketed as a fairy tale, departing from historical facts in favor of something more Disneyfied. Anastasia is eight instead of seventeen when her family dies, and instead of a Bolshevik revolution, we get Rasputin as an undead wizard who sparks the fall of the Romanovs through black magic and has a talking bat for a sidekick. The lost princess, suffering from amnesia, grows up in an orphanage as "Anya" until she is scooped up by two shysters who see her as an ideal candidate for their scam. One of them—Dimitri—falls for her while gradually realizing that she really is the true Anastasia. Anya reclaims her identity, reunites with her grandmother, and defeats Rasputin, but decides to elope with Dimitri. Other animated Anastasia films mimicked this fairy tale style (two knockoffs, by Golden Films and UAV Entertainment, also came out in 1997). 2007: The last two Romanov bodies are located, and further DNA testing confirms their identities. Some people still try to challenge this or cling to the idea that some of the Romanovs escaped, but at this point it's clear that the entire family died that night in 1918. Exploring the implications Why was it Anastasia, and not any of her siblings, who inspired such fervor? It wasn’t even clear whether the missing body was Anastasia’s or Maria’s. And there were definitely impostors posing as other surviving Romanovs. The name "Anastasia" means "resurrection," which is a romantic coincidence... but the real reason may be much more mundane. It was Anna Anderson. She was more famous than any of the other impostors. And notably, she was originally supposed to be Tatiana. That idea quickly fell apart, partly because she was the wrong height. But whose height matched? Anastasia's. And so Franziska Schanzkowska found her new identity, and Anastasia is now the central figure of a myth because her height matched up with a scammer's. Somehow this makes it feel even more deeply sad. With Don Bluth’s film, a new fairy tale really took shape. And it wasn't the story of Anastasia. It was the story of Anna Anderson—the myth that she and her supporters created around herself, of a lost princess regaining her memories. Maurette's play, and its many derivatives (the 1956 film, Don Bluth's film) tell the narrative of crooks coaching a woman to play the part of Anastasia. This is exactly what detractors accused Anderson and her supporters of. The real story of Anastasia Romanova is a life cut short by brutal violence. Anna Anderson’s fairy tale, by contrast, is romantic and enjoyable. It relies on a very old and widespread trope: the random orphan who discovers that they’re the long-lost heir to the kingdom. Herodotus told a story like this about Cyrus the Great being raised by a shepherd. It's in the story of King Arthur. It's in the Italian fairy tale “The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.” It’s in Madame D'Aulnoy’s fairy tale “The Bee and the Orange Tree” and in the original, highly convoluted "Beauty and the Beast" by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve. It’s Shasta in The Horse and His Boy and Cinder in The Lunar Chronicles. It’s Disney’s Briar Rose and Hercules and Rapunzel (and, oddly enough, also the Barbie version of Rapunzel from 2002). (One unusual touch of the Anastasia myth is that the princess is a little older when she vanishes - not an infant - and amnesia is a lot more likely to be in play.) What's especially interesting is the way the story may have evolved since the graves and DNA tests. In the Maurette-verse of Anastasia stories, Anastasia may discover her true identity, but she ultimately chooses to leave behind the prestige of princesshood and its obsession with the past for a normal life with the man she loves. These stories are typically colored by the real-world context that there is no kingdom for her to go back to, that things have changed too much. What inspired this post was noticing the number of Anastasia retellings out there. I read two of them around the same time a couple of years ago--Heart of Iron by Ashley Poston (2018) and Last of Her Name by Jessica Khoury (2019), both of which are sci-fi retellings of the Anastasia myth set in space. Poston’s book draws a lot from the Don Bluth cartoon. The heroine goes by Ana and her love interest is named Dimitri. The villain has a name similar to Rasputin. There's a pivotal moment where Ana must prove her identity to her grandmother. However, the Maurette-inspired "fraud" plot is played way down, barely a factor at all. Khoury's book takes more of its creative spark from history. As Khoury said in an interview, "what if instead of ending the Anastasia story ... a DNA test was the beginning of her tale?" So it begins with the heroine, Stacia, being spotted as the lost princess via a genetic scan, and having to go on the run. Both of these new stories move away from Maurette's plotline of is-it-or-isn't-it fraud. Instead they focus on the Anastasia figure fighting to take back her kingdom and queenship. It’s much more the fairy tale brand. A 2020 film, Anastasia: Once Upon a Time, is sort of the same animal. It includes supernatural elements and evokes a fairy tale setting with its title. It heavily features Rasputin as an antagonist but features a different setup, following Anastasia traveling through time to befriend a modern-day girl. The ending allows Anastasia and her family to escape and survive, but that is an endnote, not the main plot. These are works written in a time when we know that the Romanovs died and any other alternative is a fantasy. We know that "Anna Anderson" and all the other supposed survivors were frauds. Most people reading these books probably don't even think of the individual person Anna Anderson at all. The mystery has been solved, but the myth endures. BIBLIOGRAPHY

In my last two posts, I’ve discussed two proposed candidates for a historical Snow White. Margarethe von Waldeck was a gorgeous 16th-century countess who may have been poisoned for attracting a prince's attention. Maria Sophia von Erthal was a saintly 18th-century noblewoman whose family's castle featured a magnificent mirror. Much has been made of their similarities to the story of Snow White, the theory being that the Brothers Grimm encountered local stories of one of these women. This theories suffer from a fatal flaw, namely: they are not very good. And that becomes especially apparent when we look at the fairytale itself and the mythology that would have been available to the Brothers Grimm.

In this blog post I will be looking at the following:

EARLY EVIDENCE OF THE TALE'S MOTIFS When most people think of Snow White, they think of the details provided by the Brothers Grimm. The mirror, the dwarves, etc. Now, I want to note that these details do not make up the story itself. They are just window dressing. Do not get caught up in the window dressing. But Bartels and Sander really focused on these details, so we'll go through them. There are items like the wild boar or the seven mountains, which are part of nature. There are concepts like Snow White being a princess. There are also more elaborate, colorful tropes, like the magic mirror, which appear going far back into historical literature. It would be impossible to list everything, so I will try to collect a few key works that give an idea of how long they've been around. I'm not arguing that any of these were inspirations for Snow White, just establishing that these ideas were both ancient and immediately familiar for audiences long before the time of our "historical Snow Whites." Extreme beauty: The imagery of snow-white skin and blood-red lips - often accompanied by raven-black hair or eyes - is an old description for striking beauty. This description is used for a man in the “The Death of the Sons of Uisnech,” from the Irish Book of Leinster, before 1164. A woman, Blancheflor ("White Flower"), gets the description in Chretien du Troyes' Le Roman de Perceval (c. 1180s), although she is blonde, probably because black was seen as a more masculine hair color at the time. George Peele's 1595 play The Old Wives' Tale features "a fair daughter, the fairest that ever was; as white as snow and as red as blood." Physical beauty plays a major role in the plot for ATU 709. The snow-white motif appears most prominently in the German versions, and stories in other cultures sometimes keep elements of the name. However, it's actually not that common for ATU 709. Snow is not necessary to a Snow White tale. In some Middle Eastern versions, the heroine has a name along the lines of Pomegranate. The "snow-white skin" motif appears more often in variants of “The Three Citrons” (ATU 408). A wicked stepmother: The cruel mother or stepmother is one of the most common fairytale villains. In times with high death rates, it was common for people to remarry, and the idea that a stepparent would favor their own child was very prominent. Medea and Phaedra are troublesome stepmothers in Greek myth. The trope appears in Irish myth (the Children of Lir), Welsh (Culhwch and Olwen) and Norse (Grógaldr). (See Hui et al, 2018, for more examples of cruel stepmothers in medieval Germanic literature.) For a particularly relevant example: in the 2nd century C.E., Apuleius’s Metamorphoses included a story appropriately titled "The Tale of the Wicked Stepmother". Like Phaedra, the beautiful yet depraved stepmother lusts after her handsome stepson, but he refuses her advances. Now filled with hate, she tries to serve him poisoned wine. When her own son drinks the wine by mistake, she accuses the stepson of his murder. The murder trial doesn't go well for the stepson, and things are looking bleak until a wise physician comes to the rescue. He reveals that not only did he recently sell poison to the stepmother’s servant, but he actually substituted a harmless sleeping potion. Everyone rushes to reopen the sarcophagus of the “murdered” boy just in time to see him awaken. With the truth revealed, the stepmother is exiled and her servant is executed. It’s not a Snow White story, but it has some striking similarities - the stepmother's hatred towards a beautiful stepchild, the deathlike sleep, a child awakening in their coffin. Note that the servant is tortured by having his feet burned, not unlike the iron shoes in Snow White. The motif of the noble doctor who sabotages the stepmother’s poison is more obscure, but appears in a couple of early Snow White stories, “Cymbeline” and “Richilde.” The Grimms edited many of their stories, including "Snow White," to replace evil mothers with evil stepmothers, more in keeping with their own ideals. As we’re about to see in a minute, not all ATU 709 stories have stepmothers. Biological mothers, mothers-in-law, sisters, aunts, and unrelated women can all play the role of villain. Mirrors: The magic mirror appears in numerous sources going back to medieval times. Prester John's mirror in the Middle High German Titurel (early 13th century – complete with talking and giving advice), Cambuscan's mirror in The Canterbury Tales (late 14th c.), and Merlin’s mirror in The Faerie Queene (1590) are just a few examples. Mirrors are common in versions of ATU 709, but so are cases where the jealous villain talks to the moon or a fish. It can also simply be a normal person who comments on the Snow White figure's beauty. Mining dwarves: Fairies and spirits of the dead are often subterranean, but dwarves in particular were associated with mining and metalworking. In Germanic mythology, dwarves typically dwell underground. In Norse myth, they're master smiths who create magical weapons, tools and jewelry such as Thor’s hammer or Sif’s hair of living gold. In Middle High German poetry (1200-1500), the Nibelungenlied features the treasure-guarding dwarf Alberich, and Laurin has a dwarf king who abducts a human woman to his kingdom under the mountain. Cultures across the world believed in mine-dwelling spirits, who were often described as little men or goblins. For instance, kobolds in Germany and knockers in England. These creatures might cause mischief or warn miners of impending collapse. In many areas, food was left as an offering for them. You can see echoes of this in the Swiss philosopher Paracelsus's description of elemental spirits, published in 1566. His earth spirits - pygmies, earth manikins, gnomes and dwarves - glide through solid rock and guard veins of ore. Other Snow White figures are aided by fairies, family members, cats, dragons, camel drivers, or scholars. Robber bands are especially popular as helpers. Dwarves appear in multiple German versions, and also in an Icelandic version, “Vilfrídr Fairer-than-Vala." Poison: In the Grimm fairytale, the wicked queen attempts to murder Snow White first by strangling her with a stay-lace, then by poisoning her with a comb and finally an apple. The stay-lace is an article of clothing, and shoes or ribbons are common murder instruments in ATU 709. It brings to mind Greek myth with Medea's cursed robe or the poisoned garment that kills Heracles. A comb is made up of sharp, needle-like objects. Sharp objects are, by far, the most common cause of enchanted sleep in fairytales - combs, splinters, needles, or spindles. This suggests real-life occurrences like a bite from a venomous snake, or an infection occurring from a cut. Finally, the apple. This functions a lot like the sharp objects - it is a foreign body, and when it is removed, Snow White awakens. In the Grimm tale, Snow White is not awakened by a kiss, but by being struck so that the apple chunk flies out of her throat. This is similar to other tales where the awakener is not the prince himself, but his mother or another family member. The concept of an apple as an instrument of death would have been immediately familiar to western Christian audiences, who depicted the fruit eaten by Eve as an apple. The fruit is directly tied to death: "But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die." And in Greek myth, the story of the golden apple of discord connected the fruit with beauty and jealousy. When the apple was presented as a prize for the most beautiful goddess - i.e. the fairest of them all - the contest sparked a bitter argument over who should win, ultimately causing the Trojan War. The enchanted sleep: It doesn't necessarily need to be sleep; it can be death, or a state like death, followed by resurrection. Note in particular the 13th-century Old Norse Völsunga saga, where Brynhild the Valkyrie is cast into a deep slumber by a sleeping-thorn (see the aforementioned sharp objects). This myth convinced the Grimms that "Sleeping Beauty" had Germanic origins and belonged in their collection. EARLY EVIDENCE OF THE TALE'S PLOT Now let's get into the actual bones of the story. Snow White is categorized as type 709 in the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Tale Type Index, and is widespread in Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia. It's important to note that the Grimms' version is not a "canon" or "main" version of the story, just one unique variant. Different people have broken the story down to its parts, but the basic gist is this: an older woman becomes jealous of the beautiful heroine. The heroine is forced into exile, possibly spared by a sympathetic executioner. She finds a home with allies who give her shelter. The older woman discovers this and successfully kills her, or at least puts her into a coma. The heroine's body is placed on display, but then she is revived and gets married. Graham Anderson suggested that ATU 709 can be traced to the myth of Chione ("Snow"). In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the god Mercury causes Chione to fall asleep so he can rape her; Apollo, disguised as an old woman, does the same. Chione gives birth to twins, but when she boasts of her beauty, she is killed by the goddess Diana. In my opinion, Anderson has some interesting points but takes too many leaps in logic. For one thing, he puts too much emphasis on the heroine's name relating to snow. I think it's a mistake to identify Chione as a Snow White figure. Other stories like The Lai of Eliduc (late 12th century) have also been compared to Snow White, and Andersen makes an intriguing case for The Ephesian Tale of Anthia and Habrocomes (pre-2nd century), but I'm going to keep this short by focusing on those that have the clearest plot similarities. Cymbeline by William Shakespeare (1623) features a princess named Imogen. She is very beautiful, described in terms of white and red (she is a "fresh lily,/ And whiter than the sheets!" with lips like "Rubies unparagoned"). Her wicked stepmother tries to poison her, but a helpful doctor secretly swaps the poison with a sleeping potion. For unrelated reasons, Imogen flees into the forest, where she is given shelter by a group of men. She eventually takes the sleeping potion believing it's medicine. The men think she's dead and sadly lay her body out in state. She later reawakens, and at the end is joyfully reunited with her companions and her husband. Some scholars argue that this is too fragmented and Cymbeline is more inspired by other works. It's true there are a lot of influences, both historical and literary, in this very busy play. However, I don't think we can ignore its core similarities to ATU 709. Cymbeline combines many folktale tropes, and we could be looking at echoes of an English Snow White story here. “The Young Slave,” by Giambattista Basile (1634) has similarities to Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, and stories of the "Supplanted Bride" tale type. The heroine, Lisa, is raised by fairies but cursed to die via a comb stuck in her hair, and her body is placed within seven nested crystal coffins. Her uncle keeps her in a hidden room. Her uncle's wife finds her and, jealous of her beauty, knocks the comb out of her hair - accidentally awakening her in the process. The aunt forces Lisa to work as a slave until the uncle finds out and sets things right. “Sun, Moon, and Talia,” also from Basile, similarly resonates with Snow White. Talia apparently dies by means of a splinter under her fingernail. A king finds her in the woods and rapes her. She gives birth to twins who suck the splinter out of her finger, waking her in the process. The king's jealous wife wants Talia executed and tries to have the twins cooked and eaten. A sympathetic cook secretly hides the children and substitutes lamb meat. When the king finds out what's going on, he executes the queen and marries Talia. "Sleeping Beauty" by Charles Perrault (1697) is a softened adaptation where the rape is omitted and the rival wife is changed to the king's mother. Interestingly, "jealous queen" figures only appear in the final acts of these Italian and French tales. They are not the cause of the enchanted sleeps. Snow White makes more narrative sense, and modern renditions of Sleeping Beauty almost always cut the second half of the story. Syair Bidasari (18th century?): In this Malay poem, a queen becomes fearful that another woman will catch the king’s eye, and sends out spies to seek anyone more beautiful than her. They tell her of the lovely young Bidasari. Learning that the girl’s life is connected to a fish, the jealous queen takes the fish out of the water. This causes Bidasari to seemingly die during the day, only awakening at night. For safety, her parents hide her at a remote location in the desert. However, the king discovers Bidasari's body and falls in love with her. When she’s conscious at night, she tells him her story, and he returns the fish and takes her as his new queen. The former queen is left in solitude to repent. The surface details may be different, but it completes the core plot of Snow White in a way that none of the previous examples do. Similar tales have since been collected in India and Egypt. The poem’s date of origin is uncertain; the oldest surviving manuscript is dated 1814, the oldest mention of the title is from 1807, and it is probably older. Another poem of this genre was theorized to have been composed sometime after 1650. This story is one we know can't have influenced the Grimms, but it shows an independent strand of the tale from a completely different part of the world around the same time. The Tale of a Tsar and His Daughter (1710s-1730s?): This Russian text has been discovered only recently, and is tentatively dated to the early 18th century. The role of the magic mirror is played by a beggar who praises the princess's beauty. Her jealous stepmother orders her killed, and the servants bring her severed finger as proof of her death. The princess takes refuge at the home of nine brothers, keeps house for them, and slays a serpent to rescue them (!). The stepmother learns of her survival and sends a poisoned shirt which kills her. The brothers build a tomb for her and also die. A prince finds her body, falls in love with her, and takes her home, where his mother removes the poisoned shirt and revives her. The brothers are resurrected, the prince and princess celebrate their marriage, and the stepmother is punished. I still need to investigate further, but this could be competition with Syair Bidasari for the earliest full version of Snow White discovered so far. (Kurysheva 2018) “Richilde,” by Johann Karl August Musäus (1782): This novella appeared in Musaus’ Volksmärchen der Deutschen, a collection of literary folktale retellings. The vain Richilde becomes violently jealous of her lovely stepdaughter Blanca ("White"). She makes three attempts to kill her with a poisoned apple, soap, and a letter. However, her apothecary has secretly made the poison nonlethal and the gifts only leave Blanca unconscious and mistaken for dead. Her coffin has a glass window that allows people to look in at her, and she is rescued by a knight who heals her with a holy relic. Richilde is punished by being forced to dance in red-hot iron shoes. There’s even the rhyming chant to a mirror: "Mirror white, mirror bright, Mirror, let me have a sight, Of the fairest girl in Brabant!" It feels surprisingly modern; it’s told from the wicked stepmother Richilde’s point of view, and the magical elements are mostly downplayed or given scientific explanations. For instance, Blanca is attended by court dwarfs (real people with dwarfism, forced to serve as royal attendants and jesters). From "Richilde" we can deduce that the story of Snow White, in more or less its modern form, was already well-known in Germany by the 1780s, enough for Musaus to write an elaborate, satirical version from the villain's point of view. The Tale of the Old Beggars (1795): a Russian folktale published anonymously. This is very close to "The Tale of a Tsar and His Daughter." Some differences: the heroine, Olga, is a merchant's daughter rather than a princess. Olga doesn't kill a dragon, but is instead possibly the most clueless Snow White ever - she tells her stepmother she’s alive by sending her some pierogis. The poisoned shirt is studded with pearls. The grieving robber-brothers build a crystal tomb for Olga and die, but are not resurrected. The conclusion with the prince and his mother is the same. The Beautiful Sophie and Her Envious Sisters (1808), by Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff. This version came from Silesia, possibly with Polish influence. (Kawan 2005, 238-239). It features a magic mirror and a glass coffin. The villains are the heroine's two evil sisters, who try to kill her with a hair ribbon and an apple. Instead of seven dwarves, there's one little old lady. Snow White (1809), a play by Albert Ludwig Grimm (no relation to the Brothers Grimm). Here we have an evil stepmother and stepsister. Snow White takes refuge in a glass mountain with a whole kingdom of dwarves, and is given a poisoned fig. And, finally, the Grimms' "Little Snow-White." The Grimms had a strikingly different goal from authors like Basile or Musaus. Rather than using folklore as fodder for a unique literary creation, they set out to preserve the original oral tales. Their "Snow White" was a mixture of stories from at least three informants - Marie Hassenpflug, Ferdinand Siebert, and Heinrich Leopold Stein. Christine Shojaei Kawan states that the Brothers Grimm considered Snow White one of the most popular fairytales. (Kawan 2005, 238-239). The Grimms' 1810 draft - presumably the closest to the first versions they collected - has some startling differences from the tale we know. Snow White is a blonde with eyes as black as ebony, and the villain is her biological mother. Her hair was changed to black by the time they published their work in 1812. Starting with the 1819 edition, the mother was changed to a stepmother. This change may have been to soften the tale for children, but also remember that the Grimms collected and combined many versions. Their notes mentioned variants with stepmothers or adoptive mothers. In one version there's a talking dog named Mirror rather than a literal mirror. The Grimms published many other fairytales which overlap with Snow White, including “Cinderella” (evil stepmother), “The Juniper Tree” (evil stepmother murders her snow-white/blood-red stepson), “The Three Ravens” (the girl’s arrival in the ravens’ home), “Briar Rose” (enchanted sleep), and “The Glass Coffin” (rescue of girl from a glass coffin). HISTORICAL FIGURES IN FAIRYTALES We do have many cases of real people and places that either inspired legends or were adopted into legends. For instance, Caliph Harun al-Rashid appears in many of the stories in The Thousand and One Nights. Richard the Lionheart is given a Melusine-esque fairy mother in a 14th century romance. And Bertalda of Laon, Charlemagne's mother, starred in a Goose Girl-like story from manuscripts around the 13th century. Most of these stories were recorded long after the original people died. However, it is entirely possible for legends to spread while the subject is still alive. For a modern example, in 1936, a Newfoundland girl named Lucy Harris went missing and was found alive in the woods eleven days later. Her story quickly evolved into a tale of fairy abduction. By 1985, 49 years later, it was well-known across Newfoundland, but was still closely tied to the name and location. When folklorist Barbara Rieti investigated, she was directed straight to Harris’s then-current residence. Even more important: Rieti noted that Harris’s story was boosted by radio and newspapers. Comparable stories with similar timeframes, that didn't receive media attention, stayed within small local communities. WHY THE HISTORICAL THEORIES JUST DON'T WORK The proposed "historical Snow Whites” are too late to have sparked the worldwide tale of ATU 709. By the time of Maria Sophia, there were strong alternate traditions in Russia and Malaysia. Margarethe and her family were earlier, beating out Shakespeare by a hundred years, but I would say she was also too late; we're talking about an incredibly widespread tradition of stories, with all kinds of variations far beyond anything we find in the Margarethe theory. Instead, the theory must be that these women influenced local German versions of ATU 709. That is, they were the source of colorful local details like the poisoned apple and the helpful dwarves. But this still isn't supported by the facts. There is not a single unique characteristic of the German Snow White that can be traced to either of these women. The best they can offer is faint coincidence. Deadly poisoned apples? There were orchards in the area. Helpful dwarf miners? There were mines in the area. A trip across seven mountains? You got it - there were mountains in the area. These theories focus on the shallowest details of the story rather than on the core plot, and they don’t even do that very well. The Maria Sophia theory totally collapses at the first sign of scrutiny. Even if we ignore that this theory started as a joke by three guys in a pub, the timeline doesn't work. As said before, there were less than 40 years for her life story to diffuse into the German fairytale and her real name to be forgotten. Compare the case of Lucy Harris: 50 years, widespread media attention, and her name and location stayed inextricably tied to the story. The Margarethe theory has two small advantages over Maria Sophia. First: the three Margarethes were born in the 1500s, giving a bit more time for their lives to be mythicized and for storytellers to combine them into one person - but still not a lot of time. Second: Sander's theory was apparently spurred by a local claim that Snow White's dwarves were inspired by the Bergfreiheit mines. But this still doesn't work. The concept of subterranean dwarves is ancient, far older than the Bergfreiheit mines. Ultimately the Margarethe theory falls prey to the same problem as the Maria Sophia theory: this is just a marketing stunt with nothing real to back it up. Both Sanders and Bartels went about their theorizing backwards. They looked for historical noblewomen from specific areas who could fit the story, and then performed any contortions necessary to cram their histories into the shape of the Grimm fairytale. By their logic, any woman could be the real Snow White as long as she had a stepmother and someone once ate an apple within a 100-mile radius of her. There have been other theories about historical Snow Whites. An author named Theodor Ruf, inspired by Bartels, jokingly suggested that Snow White could have been a different woman from Lohr: a medieval woman named Agnes, from the family of the Counts of Rieneck. But this never took off in the same way - that is, it was never picked up as a marketing tool. Folklore academics have reacted to the "historical" theories with skepticism or outright scorn. Folklore professor Donald Haase called the historical figure theories “pure speculation and not at all convincing.” Heidi Anne Heiner, who runs the SurLaLune site, points out that “it is always dangerous to assign fairy tales to actual historical personages,” comparing the many proposed historical Bluebeards. Christine Shojaei Kawan dismissed Bartels's theory entirely, knowing that it was a joke (Kawan 2005). Rather than these women inspiring the fairytale, it's the other way around. Snow White, at least in the past 30-40 years, has come to influence the way we tell the stories of Maria Sophia and Margarethe. I do want to focus on one thing I've discovered: German storytellers had all the elements of "Snow White" at their fingertips long before Maria Sophia or even Margarethe were born. I'm also delighted that even now we are still discovering old manuscripts like "The Tale of a Tsar and His Daughter" which could shed further light on the history of the fairytale. Ultimately, I'd guess that "Snow White" is far older than we realize. OTHER BLOG POSTS IN SERIES

SOURCES

Last month, I discussed 18th-century philanthropist Maria Sophia von Erthal, theorized to be the "real" Snow White. Not long after this theory was published, a similar argument was made for a completely different candidate. The theorist this time was Eckhard Sander, a mathematics and German teacher from Borken. The Maria Sophia theory had a playful feel; even its creator didn't take it too seriously. This next theory is its darker, edgier sister. Sander's candidate for Snow White was Margarethe von Waldeck. This stunningly beautiful young woman lived near a mining town which used children as laborers. After her father remarried, she was sent away from home. Ultimately, she was poisoned for her beauty and died young - assassinated because a prince fell in love with her. This theory seems pretty simple on its face, but it’s actually much more elaborate. Sander’s theory is not exactly that Margarethe von Waldeck was the real Snow White. Instead he proposes that the tale of Snow White originated in Waldeck in the late 16th century, with the plot points drawn from local legends and the main character a composite of three different people all named Margarethe. Margarethe von Waldeck (1533-1554): The Beauty Location: Bad Wildungen, Hesse Margarethe was the daughter of Philip IV, Count of Waldeck and his wife Margarethe von Ostfriesland. They lived in the town of Bad Wildungen, in the mountain range known as the Kellerwald. Young Margarethe was exceptionally beautiful, with blonde hair. This might sound like it rules her out - Snow White is supposed to have ebony-black hair, after all - but it's a little-known fact that Snow White was blonde in the Grimms' 1810 draft. Margarethe was the seventh or eighth child in the family. In 1537, when she was four, her mother died in childbirth. In 1539, Philipp took a second wife, the widowed Catharina von Hatzfeld. Sander hints coyly that perhaps Catharina was jealous of her lovely stepdaughter, but he presents little evidence for this. However, Margarethe was apparently sent to live elsewhere at a young age. Catharina died in 1546. At some point, Margarethe was sent to the royal court of Brussels in Belgium. ("Richilde," a 1782 version of Snow White, also takes place in Belgium.) She attracted the romantic attentions of Prince Philip, later to be King Philip II of Spain, but then she fell ill and died in the year 1554. She was just 21. According to rumor, she had been poisoned. Was this the work of political rivals who didn't approve of the relationship? Later that year, Count Philipp IV married his third wife, Jutta of Isenburg-Grenzau. Margarethe's brother Samuel also got married that year. From their father he inherited land including a mining settlement, which would eventually become the town of Bergfreiheit. He put up boundary markers called Bloodstones (Blutsteine). Sander compares this to an obscure Snow White variant from the Grimms' notes: driving through the woods, a count and countess see three piles of snow, three pits of blood, and three black ravens, prompting the count to wish for a girl of those colors. Samuel built up the local copper mines and granted miners additional freedoms. However, there was a dark side to the industry. Children were used as miners because they could squeeze into the small tunnels. They lived in terrible conditions, many of them stunted in growth and prematurely aged due to their work, so that people referred to them as dwarfs. Large numbers were crammed into small houses with only a couple of rooms - hence, says Sander, the idea of the seven dwarfs living in a tiny cottage. Margarethe von Waldeck (1564-1575): The Child Margarethe was the youngest child of Samuel and his wife, Anna Maria von Schwarzburg. She shared a name with her paternal grandmother and aunt. She had six older brothers, all of whom died in infancy except for one, Günther. Samuel died in 1570, when little Margarethe was six. Anna Maria had been carrying on an affair with Samuel's secretary, Göbert Raben, and they secretly married after his death. The scandal infuriated her relatives, who tried to nullify the marriage. A family genealogy suggests that Anna Maria's licentious behavior continued even after she married the secretary (although I suspect some bias here). Margarethe was sent to live with relatives. In 1575, at the age of just eleven, she fell from a cliff while picking flowers and died. Sander compares this to a variant mentioned in the Grimms' notes - here, rather than sending Snow White with the huntsman, the queen takes Snow White into the forest herself in her carriage. She tells her to pick some roses, and then drives off, abandoning her. Sander also takes note of Margarethe's young age; one early manuscript of Snow White described the heroine as an "unfortunate child." In 1576, a year after her daughter's death, Anna Maria and her lover were imprisoned. Her lover was released after two years and sent into exile, but Anna Maria spent the rest of her life shut up in a convent. A dead child. A perverse mother figure imprisoned for her crimes. Out of this history, Sander picked another Snow White story. Margarethe von Waldeck (1559-1580): The Bride Margarethe was the daughter of Johann I von Waldeck, from another branch of the same family. In 1578, at age nineteen, she traveled to marry Count Günther von Waldeck (her distant cousin, Samuel's son, Margarethe I's nephew, Margarethe II's brother). It was an elaborate wedding with an elite guest list, processions, feasting, and a four-day-long afterparty. Sander tied this to the wedding and happily-ever-after of Snow White and her prince. But even this Margarethe didn't get a happily-ever-after; she died childless two years after the wedding. A couple years after that, Gunther took a second wife, also named Margarethe. Folktales of Bad Wildungen Sander bulked up his theory with various legends and historical facts from around the area.

Inaccuracies and problems As with the Maria Sophia theory, there are a few inaccuracies that pop up now and again in articles on the subject. Again, these generally have to do with lines between the history and the fairytale being blurred. Claim: Catharina had something to do with her stepdaughter Margarethe's poisoning. Most people correctly spot that this is impossible, since Catharina died long before her stepdaughter. In fact, in his original book, Sander actually focused on Margarethe II's mother, Anna Maria, as the inspiration for the "evil queen" character. Claim: This is a portrait of Margarethe von Waldeck. This is Irish writer Marguerite Gardiner, Countess of Blessington (1789-1849). This is a mistake spread through various online articles and I'm not sure where it started, but I'd guess someone thought this woman looked Snow White-like and got confused by the fact that she was a countess named Margaret.

Claim: Margarethe's shaky handwriting on her deathbed will is a clue that she was poisoned. This one is honestly confusing; a dying woman having shaky handwriting is not weird. I think this may be misleading wording, with the idea stemming from a 2005 German documentary titled Snow White and the Murder in Brussels. It was 45 minutes long and put forward the theory that Margarethe had been poisoned with arsenic. Dr. Gerhard Menk, a historian interviewed in the documentary, stated: "When she wrote the will, it was absolutely clear to her that her life would not last very long. The will shows clearly blurred handwriting. She wrote with a hand that was shaky. And in this respect death is foreseeable relatively early." As for the viability of the Margarethe theory . . . Sander pulls from everything he can find in history and in the Grimms' manuscripts. Blonde hair and a stepmother from Margarethe I (even though in the Blonde Snow White draft, her biological mother is the villain). Two more Margarethes to provide any missing Snow White-esque details. Poison apples from a local legend - never mind that they bear no resemblance to the poison apple in Snow White. And I feel like Sander makes too much of the young Margarethes being sent to live elsewhere. He implies that family drama was the cause, particularly that the mother or stepmother was to blame. Maybe this was the case for Margarethe II. But historical nobility often sent their newborns off to wet nurses, which could mean being away from them for long periods of time. Some royal parents were very involved with their children's lives, but even they might send their children to be raised and educated elsewhere. Princes like Edward VI of England had their own households when they were still young children. In particular, Margarethe I going to Brussels would have been a natural step for a teenaged noblewoman, a huge opportunity for her education and marital prospects and a strategic political move for her family. Where did this theory come from? Sometime before 1990, Eckhard Sander was writing a term paper for a course at the Justus Liebig University. He was interested in writing about the history of child labor in mining, so he and his family toured a Bergfreiheit copper mine. Their guide claimed that the sight of the children in their protective felt caps emerging from the mountain had inspired the dwarfs of "Snow White." Intrigued, Sander sought more evidence with help from his professor Gerd Rötzer. Sander was aware of the Hansel and Gretel hoax from the '60s, but unlike the Lohr "study group," he preferred to distance himself from it. He dove deep into the history of the Grimms' work and the various drafts of Snow White, and concluded that fairytales contain a kernel of truth, unconscious memories of real events. The Grimms would have collected the story of Snow White while unaware of the events that had shaped it only a couple of centuries before. Tiny, easily-missed details in the various versions still pointed to the real history. In 1990, Sander submitted his term paper under the title "Snow White: Fairytales or Truth? An attempt to localize KHM 53 in the Kellerwald." He published it as a book in 1994, with a slightly different subtitle, A local reference to the Kellerwald. This enjoyed similar success as the Maria Sophia theory. Bergfreiheit now hosts the tourist destination of Schneewittchendorf (Snow White Village). Sander was involved in the making of Snow White and the Murder in Brussels. In 2013, he wrote another book in collaboration with the city of Bad Wildungen, The Life of Margaretha von Waldeck, which is available directly from Bergfreiheit gift shops. Based on Sander's story of the mine tour, at least some locals were already claiming Snow White as their own, which would have added to the momentum. But Margarethes II and III - the Child and the Bride - seem nearly forgotten, even though they provided key plot points for Sanders’ elaborate patchwork version of Snow White. Margarethe I is the famous one, who had her death dramatized in the Murder in Brussels documentary. This is probably because spreading Snow White to multiple historical figures weakens the appeal of the theory. It's basically admitting that you don't have a good argument. Margarethe I is the one best able to carry the theory on her own, so she gets the limelight. Conclusion There are many parallels between the Margarethe and Maria Sophia theories. Both theories were conceived and published within a few years of each other. Both rely on the idea that the Grimms visited or lived near the area. Both focus less on the plot of the story, and more on details like the forks, the mountains, the glassware, or the ironworking. And both became popular because the local towns saw them as perfect tourism opportunities. Karlheinz Bartels and Eckhard Sander both went digging through history for women who matched Snow White's description. In doing so, they were proponents of euhemerism, the theory that legends are based on real people. But what if we don't set out looking for a specific historical personage? What if we look at the history of the actual folktale? Next up: Snow White. OTHER BLOG POSTS

SOURCES

Multiple towns in Germany feature Snow White-themed tourist attractions. However, two of them stand out; both claim to be the birthplace of a real woman who inspired the fairytale. In this blog post, I'll be looking at the first woman to be proposed as "the real Snow White." As the usual summary goes, this kind-hearted young woman suffered under the authority of a harsh stepmother. In their castle hung an elaborate mirror said to speak. They lived in a forested area near a mining town with very short workers. But upon investigation, there are a lot of inaccuracies being passed around. Maria Sophia Margaretha Catharina von Erthal (1725-1796) Location: Lohr am Main, Bavaria Maria Sophia was born in 1725 (some sources incorrectly say 1729), one of ten children of the baron Philipp Christoph von Erthal and his wife Maria Eva. (They had seven sons and three daughters, although some died young). A family genealogy remembered her as kind, pious and generous. Maria Sophia caught smallpox when she was young, leaving her mostly blind. It's possible this also left her with facial scarring. However, the painting above - which is believed to be her portrait - does not show any scars. Maria Eva died, and in 1743 Philipp married the widowed Claudia Elisabeth von Reichenstein. She had two children from her previous marriage. Maria Sophia would have been 18 at the time of the wedding. According to the theory, Philipp's status seemed kinglike to local townspeople. His absences on long work trips paralleled the absence of Snow White's father in the fairytale. As for Claudia: in 1992, historian Werner Loibl uncovered a 1743 letter that she wrote while Philipp was in England on state business, not long after their wedding. The letter shows that Claudia read and responded to his mail while he was out of the country, and that she suggested her son's former tutor for a government position. Based on this, Loibl painted her as a domineering wife and stepmother. The area of Lohr features thick woods, like the wild forest of the fairytale, and seven mountains beyond which lies the mining town of Bieber. The miners would have been short-statured in order to enter the small tunnels. The Grimm fairytale mentions that the dwarfs live beyond seven mountains. Lohr's local industries included metalworking, glassworking, and especially high-quality mirrors - tying into the fairytale's iron shoes, glass casket, and magic mirror. The mirrors could be considered to "speak" or "tell the truth" because they showed particularly clear reflections, and/or because they came inscribed with traditional mottoes. Maria Sophia's family owned one such mirror, a magnificent red-and-silver-framed looking glass 1.6 meters tall (5.25 feet) which is still in the Lohr Castle, now a museum. The frame is decorated with the phrases "Pour la recompense et pour la peine" ("for reward and for punishment", accompanied with an image of a palm, a flowering branch, and a crown) and "Amour propre" ("self-love," with an image of the sun shining on a flower). Some online articles state that the mirror was made as a wedding gift for Claudia; however, historian Wolfgang Vorwerk suggests that the mirror may have already been in the castle when Philipp took office in 1719. Maria Sophia never married. At some point, she moved sixty miles away to the town of Bamberg, which runs across seven hills each topped by a church. I’m not sure when she moved, but we do know that her brother Franz Ludwig took office as the town’s Prince-Bishop in 1779. She spent her final years in the care of a convent school, the Institute der Englischen Fräulein. She died in 1796, aged 71, having spent her life doing charity work. History records indicate that she was beloved by the community. Her gravestone, rediscovered in 2019, reads "The noble heroine of Christianity: here she rests after the victory of Faith, ready for transfigured resurrection.” Two other notes: Apple orchards are common in Lohr. Belladonna, which causes paralysis, grows wild in the area. Supporters of the theory connect this to the poison which causes Snow White’s deathlike sleep. It is also an aphrodisiac, explaining the instant love between Snow White and her prince. Inaccuracies and problems In my research, I've encountered a few questionable statements that are repeated by many sources. Claim: Claudia was a harsh stepmother who disliked her husband's children. This is an exaggeration of Werner Loibl's article. Based on a single letter, Loibl concluded that Claudia was a bossy, self-serving woman who, only months after the wedding, was already using her new husband's position to advance the interests of her old employees and, presumably, her biological children as well. I'm not a historian, but I feel this is an overly negative reading for just one letter, with lots of jumps in logic to cast Claudia in the worst possible light. How do we know Philipp didn't ask his wife to handle things during his long absences? Even with that, there's little to indicate that she disliked any of her stepchildren, let alone Maria Sophia. I see no evidence that there was any kind of family dysfunction here. (Remember Werner Loibl, we'll come back to him in a minute.) Claim: Maria Sophia was forced to flee over the mountains to Bieber after being abandoned or attacked. This came from one of Lohr's tourist attractions, the Snow White-themed mountain hiking trail. As early as January 1999, the town's website featured a "Snow White" section under its tourism department. This page is written in the first person, narrated by “Maria Sophia... popularly known as Snow White.” Other than the nickname, it begins close to real life by describing her family tree. But it takes a turn when she explains that her father ran Lohr’s mirror manufactory and one day gave a mirror to her stepmother. "Incidentally, this mirror still hangs in my parents' castle in Lohr a. Main and bears the inscription "Elle brille á la lumiére", roughly translated "She is as beautiful as the light". As you know, my stepmother thought she was particularly beautiful, and when one day - I had grown a bit - the mirror no longer rated my stepmother as the most beautiful in the country, the forester took me (at her behest) for a "Walk" in the forest. We walked out through the Upper Gate and then uphill to where the Rexroth Castle stands today. At the very top, in the deep forest, the forester drew his knife. Then I suspected evil and, full of panic, ran right into the forest and downhill as fast as I could. There was a couple of shots behind me. Full of horror I ran on until, past the glassworks in Reichen Grund, I came to the Lohrbach. Did my evil stepmother actually want to kill me?" From here on, “Maria Sophia” explains step-by-step how she made her way to the mines, with a laundry list of landmarks (“Towards evening I reached the retention basin of the Bieber mines, the Wiesbüttsee...”). The story concludes by stating that she “found shelter with the seven dwarfs." It adds a link for website visitors to book the hiking trail - a deal which comes with a visit to the museum in "Snow White's family castle," a hotel stay, and a souvenir gift. This isn't a historical document - it's a hiking guide, as should be obvious from the list of locations. It presents a story with no connection to reality - the Snow White tale with Maria Sophia's name smacked on. This has set the tone for Lohr’s marketing ever since; some mistakes are corrected in modern brochures and materials, but the misleading tone remains, and other sources repeat these blurred lines. This webpage also includes another commonly-repeated error... Claim: The motto on the von Erthal mirror is "Elle brille à la lumière" (She shines like the light). The phrase is reminiscent of the Grimms' 1857 edition of fairytales, in which Snow White is described as "beautiful as the day." However, this phrase does not appear on the "Amour Propre" mirror in the castle. It was a common inscription for other Lohr mirrors in general, accompanied by an image of a pearl in an oyster. There were many other traditional emblems - see this digitized book from 1697, Devises Et Emblemes Anciennes & Modernes tirées des plus celebres Auteurs. Wolfgang Vorwerk states that the "Amour Propre" mirror was not explicitly tied to the Maria Sophia theory at first. The media probably began describing it as the fairytale mirror sometime between 1994 and 1998 (Vorwerk 2016, p. 6). This may have contributed to the confusion about which mirror is which. Claim: Lohr mirrors were specially made to echo people's voices through a trick of acoustics. This seems to be a misunderstanding of the saying that the mirrors spoke. It probably originated with a 2002 news article, reprinted around the world, which called the mirror an “acoustic toy” (Hall). Claim: Maria Sophia died of belladonna poisoning. False. This might be confusion with Margarethe von Waldeck, who I'll discuss in my next post. One thing I have to mention: the timeline here seriously strains credulity. Maria Sophia's father remarried in 1743. The Grimms' first draft dates to 1810, 67 years later. But the Grimms weren't the first to write down the story; that was Johann Musäus's "Richilde," published in 1782. Although this version was an elaborate satirical novella, it's clearly a retelling of the same folktale the Grimms would later transcribe. Maria Sophia was still alive at this point. If she truly originated the fairytale, or even just influenced it, it would have had no more than 39 years to evolve into its current form and spread across all of Germany. And there's no evidence that this happened. Thomas Kittel’s 1865 genealogy listed Maria Sophia as one of the more notable von Erthals, giving her one and a half pages of biography. In comparison, some of her siblings are barely mentioned. And yet there's nothing to indicate that she inspired any Snow White-esque legends. Kittel's description gives only the impression of a deeply religious woman with a disability who lived a normal, fulfilling life. Where did this theory come from? First, some stage-setting. In 1963, Germany was rocked by a newly released book. Die Wahrheit uber Hansel und Gretel (The Truth about Hansel and Gretel) revealed that the famous fairytale was based on a gruesome true story. The siblings were not children lost in the woods, but a pair of 17th-century bakers from the Spessart forest who brutally murdered a rival for her gingerbread recipe. Photos showed a researcher named Dr. Ossegg unearthing the ruins of the "witch's" home. Except that in 1964, the real truth came out: it was all a joke. The events were made up, the evidence was forged, and "Ossegg" was actually the author Hans Traxler in a fake mustache. The hoax fooled many, and some believed in it even after the truth was revealed. One disappointed reader tried to report Traxler for fraud. Flash forward to 1985. In Lohr am Main, a town on the opposite side of the Spessart from the "site" that Traxler had "discovered," a few men started a study group on fabulology. Fabulology was their own newly coined term for "fairytale science." The group consisted of pharmacist Karlheinz Bartels, local museum head Werner Loibl, and shoemaker Helmut Walch. And by "study group" I mean that they hung out at the local wine house together. In a 2015 interview, Bartels explained that they were inspired by the Hansel and Gretel hoax: "We said to each other at the regulars' table [of the wine house] that we need something like that for Lohr." Although satirical, Traxler's book rested on the premise that the real story could be uncovered by careful deduction, and that's what the "study group" set out to do. As they brainstormed fairytales that could fit the area, Loibl - an expert on glassworking history - thought of Lohr's famously high-quality mirrors. Aha - the evil queen's magic mirror! From there, Bartels pinpointed Maria Sophia. The fabulology group had started as an in-joke, but it didn't stop there. In 1986, the magazine Schönere Heimat published Bartels' tongue-in-cheek article "War Schneewittchen eine Lohrerin?: Zur Fabulologie des Spessarts" (Was Snow White a Woman of Lohr? On the Fabulology of the Spessart). To everyone’s surprise, including Bartels's, the article took off. Bartels produced a full 80-page book, which received several editions. Loibl published articles as well, including the one about Claudia's letter. The town embraced this new marketing opportunity. At the book launch in 1990, Loibl announced that a Snow White-focused room would be set up at the Spessart Museum in Lohr Castle; the project was completed in 1992. Artifacts included "Snow White's shoes" - a pair of two-hundred-year-old children's shoes found in the castle - along with the "Amour Propre" mirror. The Snow White Trail that I mentioned previously was also created. Snow White-themed events are now held at the museum and throughout the town. The town features art installations like the pristine Snow White statue seated on a park bench for selfie opportunities, or the more . . . controversial Snow White by Peter Wittstadt, created in 2014. The effect was much like the success of the Hansel and Gretel hoax, but in this case, the details weren't fabricated. Obviously Maria Sophia's life did not match up exactly to the fairytale of Snow White, but there was just enough to make an argument. The popularity of the tourist attractions even led to some personal fame and local awards for Bartels.

And it seems Bartels’s attitude fluctuated as all this went on. In 2002 he announced, "We are satisfied that what the Grimm Brothers wrote about was really a documentary of sorts about our region… This all began as a bit of a joke in the local pub 17 years ago. But a lot of energy and research has gone into it since." (Hall) In 2019, when Maria Sophia’s gravestone was located and put on show in the Diocesan Museum in Bamberg, the joking tone seemed entirely forgotten. As stated by the museum’s director, Holger Kempkens: "There are indications - though we cannot prove it for sure - that Sophia was the model for Snow White. Today when you make a film about a historic person there is also fiction in it. So in this case I think there is a historic basis, but there are also fictional elements." A modern brochure claims that "one thing should become clear to anyone who reads [this]: Snow White was and is a daughter of Lohr," and that the Spessart Museum houses "[k]ey evidence documenting Snow White's origins." At the end it states in playful fairytale terms, "anyone who is still not convinced by our tale shall be made to pay one gold coin." The theory made an appearance in Lee Goldberg’s 2008 novel Mr. Monk Goes to Germany, a tie-in novel to the American TV series Monk. The “beautiful baroness” is referred to as "Sophie Margaret von Erthal” and its version of her life story is straight from the Lohr hiking trail advertisement: “Shortly after Sophie's mother died, her father remarried. The evil stepmother owned one of the famous Lohr "speaking mirrors" and was so envious of Sophie's beauty that she ordered the forest warden to kill the young woman. Sophie fled into the woods and took refuge with miners, who had to be very short to work in the cramped tunnels." (Goldberg, p. 88) Similarly, actress Ginnifer Goodwin - who played Snow White in the TV show Once Upon a Time - assumed that her character's alter ego of Mary Margaret was inspired by "a real-life story of a princess,” “Maria Sophia Margarita.” This was not intentional by the show’s creators, who didn’t know what she was talking about when she brought it up, but Goodwin still created a new wave of buzz for Bartels’s theory when she mentioned it in an interview. (LA Times, 2012) One historian, Wolfgang Vorwerk - who's continued the research into Maria Sophia's life - has determinedly reminded people of fabulology's joking roots. In 2016, he wrote to a Lohr newspaper stating that fabulology is not a historical argument. Essentially, says Vorwerk, it's a game of comparing the parallels between fairytale and history, with plenty of "self-mockery" and "a wine-loving wink." Similarly, the Lohr museum's website suggests that lingering questions - like who the prince was, and where Snow White held her wedding - are riddles "that only Franconian wine can answer." So that's the Maria Sophia von Erthal theory. There are some fun parallels, but the evidence is weak. The timeline is fishy. Tourism materials have intentionally confused the evidence to make it sound more like Snow White. The only proof for the stepmother's evil nature comes from a historian centuries later who was very interested in making her look like an evil stepmother. And it turns out that the whole thing started as a joke inspired by a famous hoax. Honestly, I just want to take a moment to savor how many deliciously bonkers moments this story includes. When I first saw a picture of the Horror White statue, I almost fell out of my chair. So, anyway, the evidence. We'll return to this debate, but first there's more ground to cover. Next up: the other "real Snow White," Margarethe von Waldeck. OTHER BLOG POSTS

SOURCES

I've been researching "lorialets," moonlight-loving spritesdescribed by French fantasy author Pierre Dubois in his Great Encyclopedia of Fairies. Lorialets will have to be a post for another time; Dubois' Encyclopedia is not so much a collection of folklore as it is a guide to the world of his comics, and the only real-world sources he gave for lorialets were the Chroniques Gargantuines or Grandes Chroniques Gargantuines. These are a group of 16th-century chapbooks, not to be confused with the famous Gargantua books by Rabelais. I haven't been able to track these down yet. However, my research along the way took me into some fascinating superstitions about mooncalves.