|

The cecaelia is, in modern Internet parlance, a common term for a mermaid that has octopus limbs rather than a fish tail. Another frequently used name is "octomaid." A famous example of an octopus-limbed mermaid is Disney's sea witch Ursula. I want to focus on "cecaelia," an intriguing name - both singular and plural and pronounced seh-SAY-lee-uh. Most importantly... where did it come from?

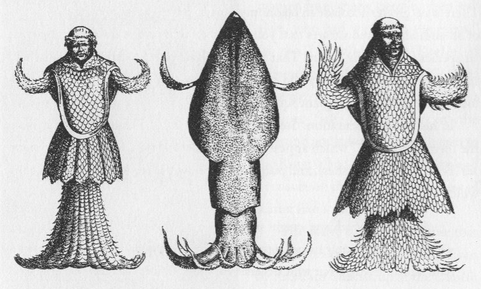

The etymology, at first look, is baffling. It starts with the same syllable as the word "cephalopod" - cephalo (head) + pod (foot) - but that's not much to go on. It is not related to the Latin girls’ name Cecilia, or to the limbless amphibians called caecilians. Both of those come from the word “caecus,” meaning “blind.” In Making a Splash (2017), Philip Hayward suggests that the word was inspired by a comic book character from the 1970s. The short comic "Cilia" appeared in Warren Publishing's Vampirella Magazine issue 16 in April 1972. It was reprinted in Issue 27, September 1973. Cilia, a beautiful mermaid-like woman with three tentacles in place of each leg, rescues a sailor from drowning. Although her appearance is horrifying to humans, she is a kind and gentle spirit and her relationship with the sailor grows into love. The story ends tragically when the prejudiced human community discovers her. Cilia refers to her species as "cilophyte." The term was probably invented by the author - the etymology, again, is murky. As pointed out on the TV Tropes page for this comic, "phyte" means growth and "cilo" could be related to "cilium" (fine hairs), Scylla (a Greek sea monster), or "kilo" (Greek for thousand). Perhaps it was also meant to look similar to "cephalopod." As Hayward points out, the word "cecaelia" does not appear until around 2007 or 2008. So I went diving. The "cecaelia" can be traced to a Wikipedia page created in March 2007. (Thank you to Wikipedia administration for their help recovering the page information!) According to the earliest version of the page, the cecaelia is "a composite mythical being." The name "is a corruption of coleoidian, a genus of squid, and derives originally from a comic in Eerie magazine from the early 1970s featuring an octopoidal character named Cecaelia" who "helped a shipwrecked sailor back to land." This is apparently meant to be "Cilia;" the plot is right, as is the publisher. Later versions of the page corrected the character information. In addition, "Coleoidea" is the subclass of cephalopods which includes octopus, squid and cuttlefish. The only source in this first version was a link to a discussion thread on seatails.org, a mermaid-enthusiast messageboard. Created by Kurt Cagle, Seatails began as a print magazine that ran briefly in 1987 and then moved to the web, shifting through several platforms over the years. In the early 2000s, it existed in a discussion board format. Members included numerous artists and collectors who were interested not only in mermaids but in other hybrid mythological creatures. The link was apparently quickly deleted, since it did not meet Wikipedia's standards for sources. Unfortunately, Seatails is now defunct and the discussion thread in question cannot be reached even through the Internet Archive. In addition to the information from Wikipedia, I contacted Kurt Cagle via the current Seatails page on the art site DeviantArt. I also contacted a DeviantArt user called EVAUnit4A, who identified themself as a user of the old message board and a contributor to the Cecaelia Wikipedia page. Based on that, here are the main points of the history of the cecaelia as I understand it:

If the comic inspired all this, why wasn’t the species term “cilophyte” adopted instead? First of all, it seems it took a while to track down the specifics of the comic. EVAUnit4A suggested that perhaps cilophyte was “too unwieldy to type out properly" and that people may have wanted "a word closer to real octopus and squid." When I reached out to Cagle, he wrote back that another influence was the song “Cecelia” by Simon and Garfunkel, about a fickle and demanding lover. According to Cagle, “I actually kind of forgot about [the cecaelia] after a while, and was surprised to find the term gaining traction a few years later.” I have to take a quick detour here. Wikipedia is near-universally used, often more easily than print encyclopedias because it’s just a push of a button away. But it can also be edited by anyone at any time. As a result, it has strict guidelines. One of the most important is that "Wikipedia is not for things made up one day." The page for this rule, which has existed since 2005, sums up many of Wikipedia's policies, including that articles must be on something notable and famous, and must include verifiable sources (such as a reliable book or article). Thus, the Wikipedia page for Cecaelia had a tortured history. Although there were quite a few works that featured such creatures, the name itself was an original creation. The page was originally Cecælia, then changed to Cecaelia, moved in 2010 to "Octopus person" as "a more proper title," and the last holdout was finally deleted in 2018. It now redirects to "List of hybrid creatures in folklore," specifically the section "Modern fiction." The word pops up occasionally on other pages - as of the time of writing, the Wikipedia page for Ursula calls her a cecaelia. As previously seen, the oldest versions of the "cecaelia" page were honest about its origins. Via the Wayback Machine, a version from December 2008 said even more definitively that the term was a "distorted mispronounced" version of Cilia. This clarification, buried in the paragraph and easier to miss, was ultimately lost. By April 27, 2010, when the page existed as "Octopus Person," the description of the comic had been deleted and only a brief and confusing reference to "Cilia" remained. Unclear language was another problem; throughout many edits, the page called the cecaelia a “composite mythical being.” A composite myth is constructed from shorter stories or fragments of tradition, often intended to recreate lost legends. However, readers could have taken the phrase in a couple of ways. In the case of the cecaelia, they might read it as “a being of composite myth based on various media," or they might read it as “a mythical being that is a composite of human and octopus.” Readers took it the second way, with many adopting the term in the belief that it was traditional. Here's one example from a blog in 2008 which specifically gives Wikipedia as its source. Looking through some of my writing from eight years ago, I found that I also used the term without a second thought after encountering it on Wikipedia. The word spread fairly quickly. The word was picked up across DeviantArt. In April 2008, a user on the roleplaying-based Giant in the Playground Forums posted a writeup for "cecaelias" as a monster race. Cecaelia was the name of an octopus-woman monster in AdventureQuest Worlds, an MMORPG released in 2008. Pathfinder's RPG Bestiary 3, released in 2011, featured the Cecaelia as a monster, and the word also features in Cassandra Clare's Bane Chronicles (2015). Most recently, the Disney tie-in novel Part of Your World by Liz Braswell (2018) refers to Ursula as a cecaelia. This was, to my knowledge, the first time Ursula had ever received this name in canonical material. Previously she was only called a cecaelia by fans, as in the fan-run database disney.wikia.com. So are there any traditional sources that feature octopus-like mermaids? In a Nootka tale from the Pacific Northwest, the animal characters Octopus and Raven show up apparently in human form. When Octopus is angered, her hair (braided into eight sections) transforms into powerful tentacles (Caduto & Bruchac 1997.) I don't know what the characters of Octopus and Raven might have been called in the original language, but according to firstvoices.com, the Nuu-chah-nulth word for Octopus is tiiłuup, and Raven is quʔušin. "The Devil-Fish's Daughter," a Haida tale also from the Pacific Northwest, features devil-fish (octopi) who can take human form. But this is more a case of animal shapeshifters, not hybrids. Native Languages, a most helpful site for American Indian legends, has little to say on the octopus. It notes only that octopi "do not play a major role in most Native American mythology." Some pages on the cecaelia, apparently derived from Wikipedia, claim that the artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) painted octopus-woman hybrids. I have found no evidence for this. Hokusai did paint the erotic 1814 “Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife," which features a woman with octopi. (If you look it up, be advised that it is NSFW.) The "sea monk" or monk-fish of medieval bestiaries also looks vaguely tentacley. Theories on what inspired it include squid and angelshark. Finally, Scylla, a sea monster of Greek myth, is said by Homer to have twelve dangling feet. She might be understood as somewhat like a squid. Homer's Scylla is not particularly humanoid, but the term has gained some popularity in recent years. Conclusion In essence, there is no traditional octopus mermaid. Only in the 20th century did the idea of octopus-human hybrids gain popularity as a symbol of horror and evil. H. P. Lovecraft's squid-faced god Cthulhu first appeared in 1928, later to influence the monstrous "mind flayers" of Dungeons and Dragons. The tragic Cilia the cilophyte, from 1972, has an appearance disturbing to humans despite her kind soul. And in 1989, Disney used the grasping, writhing half-octopus Ursula to contrast their innocent heroine in The Little Mermaid. (Their original concept art had Ursula as a more traditional fish-tailed mercreature.) However, this budding concept had no unified name. "Cilophyte" was an obscure and unique creation. "Cecaelia" was born around 2007 on the Seatails site, as a name inspired by "Cilia," "cilophyte," "coleoidea," and the alluring Cecelia of Simon and Garfunkel. Artists and other users on the discussion board popularized the title. The Wikipedia page boosted the concept, with many readers taking it to mean that the cecaelia was an established legend. At this point, it's taken on a life of its own, although there are a few other names floating around as well. In conclusion:

Sources

16 Comments

Fairy dust: maybe it’s the stuff that sparkles from a fairy godmother’s magic wand. Or maybe fairies just naturally exude it. (Or, if you delve into Disney’s expanded Tinker Bell universe, fairies need it to fly and it is a vital resource for which the characters must occasionally go on perilous quests.) Alternately, in craft stores I’ve come across little bottles of glitter labeled “fairy dust” to be used in a fairy garden. But where did the idea of fairy dust come from? I went looking for older sources which mentioned fairies in connection with dust. Some are fairly mundane. The fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, like helpful household brownies, “sweep the dust behind the door.” Okay, so that’s not really their dust. In reverse, according to Thomas Keightley, the German kobold “brings chips and saw-dust into the house, and throws dirt into the milk vessels.” Closer is John Rhys' Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, where he tells of a fisherman named William Ellis who - out on a dark misty day - saw a large crowd of little people about a foot tall, all dancing and making music. Entranced, he watched for hours, but when he approached too close, "they threw a kind of dust into his eyes, and, while he was wiping it away, the little family took the opportunity of betaking themselves somewhere out of his sight, so that he neither saw nor heard anything more of them." Similar, though it doesn't feature dust per se, is the tale of Yallery Brown. There, the titular elf blows a dandelion puff into a boy's eyes and ears. "Soon as Tom could see again the tiddy [tiny] creature was gone." George Sand's short story "La fee poussiere" was translated as "The Fairy Dust" in 1891. "Fairy Dust" in this case is the name of a character, a fairylike being who oversees everything from the earth itself to tiny particles of dust. The main character encounters her in a dream. In Félicité de Choiseul-Meuse's 1820 fairytale "The Marble Princess," a fairy godmother gives a prince "gold dust of the purest quality" to blind serpents so that he can fight them. "What Mr. Maguire Saw in the Kitchen," an 1862 story, a character waking from a disorienting dream refers to "dust . . . fairy dust that took away my five senses to the other world, and put me beyond myself." (Dialect removed.) Mary Augusta Ward's Milly and Olly: or, A Holiday Among the Mountains (1881) features a mention of a fairy throwing golden "fairy-dust" into a girl's eyes so that she sees the beauty in a certain place. There are no literal fairies in the book, but the description is significant. So far, two tales feature dreams, two have dust used to physically blind others, and the last has dust which alters someone's perception of the world. Why this connection between fairies and dust in the first place? An interesting link might lie with mushrooms. Many varieties are named for the fairies, and they have traditionally been associated with fairies in a number of ways, possibly in part because of some toadstools' hallucinogenic properties. One particular fungi tied to fairies is the puffball, a mushroom full of brown dust-like spores that are released when it bursts. Other names include "puckball," “puckfist,” “pixie-puff” or “devil’s snuffbox." (In this case, "fist" does not mean a closed hand, but a fart or foul odor. So these mushrooms were the Devil’s/Puck’s/Fairy’s farts.) In Scotland they were known as Blind Man’s Ball or Blind Man’s Een (eyes). John Jamieson suggested in 1808 that this was due to a belief that the spores caused blindness. However, it’s also possible that they were named for their resemblance to eyeballs. The mushroom connection is fun, but European puffball mushrooms are evidently not hallucinogenic. Another possible plant association: pollen, which can look like golden (yellow) dust, and which would have become a stronger link as the modern flower fairy gained popularity. The Victorian educational children's book, Fairy Know-a-Bit, or, A Nutshell of Knowledge (1866) declares that fairies refer to pollen as "gold-dust" and love "to sprinkle [it] over each other in sport."

There is another very old tie between fairies and dust. Traditionally, fairies were believed to be present in the dust clouds stirred up by the wind on the road. Any humans on the road should beware, and show respect to the otherworldly travelers. The cloud of dust might even contain kidnapped humans who were carried along with the fairies. It's been suggested that the Rumpelstiltskin-like character Whuppity Stoorie has a name meaning whipped-up dust, or stoor. For a similar concept, think of the term "dust devil" for a whirlwind. This idea may be tracked back to the 17th century at least. In 1662, accused witch Isobel Gowdie pulled from fairy lore for her confession. She described how witches, like fairies, would use tiny grass stalks as horses to "fly away, where we would, even as straws fly upon a highway" – in a whirlwind of bits of straw above the road. She added that "If anyone sees these straws in a whirlwind, and do not bless themselves, we may shoot them dead at our pleasure. Any that are shot by us... will fly as our horses, as small as straws." There's also a touch of the idea of perception here. Humans perceive only a cloud of dust, but those "in the know" realize that fairies are traveling unseen. In Teutonic Mythology vol. 3, Jacob Grimm makes a reference to witches' or devil's ashes being strewn to raise storms, and Richilde (enemy of Robert the Frisian) throwing dust in the air with "formulas of imprecation" to destroy her enemies. One more traditional connection between fairies and dust is quite sinister. In many stories, when a human returns from Fairyland, they do so without realizing that they’ve unwittingly spent centuries away from our world. King Herla, for instance, gets a nasty shock when some of his friends dismount from their horses only to crumble into dust the second their feet touch the ground. However, the key to modern fairy dust is the story of the Sandman. In European folklore, every night a mythical being sprinkles sand or dust into children’s eyes to send them to sleep and give them dreams. The sand/dust may be a way to explain the “sleep” or gritty discharge left in someone’s eyes when they wake up in the morning. E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1816 short story Der Sandmann features a sinister Sandman who steals children’s eyes after throwing sand at them. Hans Christian Andersen’s 1841 tale "Ole Lukøje" ("Mr. Shut-eye") has a gentle sleep-bringer who sprinkles “sweet milk” into children’s eyes. However, subsequent translations changed this to “powder” or “dust" as the character was gradually merged with the Sandman. There was overlap with the fairy world, and this would only increase. A 1915 dictionary defined the Sandman as "a household elf.” The children's play “Bluebell in Fairyland,” first produced in 1901, was one of the inspirations for Peter Pan. The main character's travel to Fairyland is framed as a dream. Per John Kruse's site British Fairies, the play mentions the "dustman" (Sandman) and features golden dust being strewn as the characters fall asleep and enter Fairyland. Unfortunately, the play's script and lyrics are not currently available where I can access them. Algernon Blackwood's 1913 book A Prisoner of Fairyland may also have been influenced by Bluebell. It features a “Dustman” who sprinkles golden dust “fine as star-dust” into people’s eyes to cause them to sleep. Again: sleep, dreams and fairyland are interconnected. But it was J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (play published 1904, novel published 1911) which really popularized the modern view of fairy dust. From the moment Peter Pan first physically appears in the novel, he is accompanied by fairy dust: “the window was blown open by the breathing of the little stars, and Peter dropped in. He had carried Tinker Bell part of the way, and his hand was still messy with the fairy dust.” The dust which Tinker Bell exudes bestows children with the ability to fly, and to travel to Neverland, which is made up of their own imaginative stories and daydreams. The island is first described in a sequence where the Darlings' mother examines her sleeping children's minds. When the children reach the island, they find all the locations and characters they've dreamed up. At one point Peter Pan speaks to "all who might be dreaming of the Neverland, and who were therefore nearer to him than you think." Disney’s animated adaptation came out in 1953. They altered it a little, calling the stuff “pixie dust.” Tinker Bell became an instant mascot, and her pixie dust was a callword for Disney. (They use "pixie" and "fairy" interchangeably to refer to the character, which is a post for another time.) Neverland's status as both fairyland and dreamworld is toned down in the film version, but still hinted at. The Darling children meet Peter Pan when he wakes them in the middle of the night, and - unlike the book - after they return, their parents enter the room only to find them fast asleep, as if they never left. Disney's ubiquitous Peter Pan helped popularize the modern idea of fairy dust as glittering stuff given off by fairies or pixies. It was also an important step in leaving behind the associations with dreams and, thus, the Sandman. Associations between fairies and dust are very old, seen in the whirlwind transportation and in puffball mushrooms. By the 1800s, we have mentions in literature tying fairy dust to vision, eyesight, dreams, and perception of reality. Ultimately fairies and the Sandman were equated, as were Fairyland and Dreamland. At this point, they've diverged. However, I am reminded of the 2012 animated film Rise of the Guardians, where the Sandman works with glowing golden sand that looks a lot like Disney Tinker Bell's pixie dust. Also, "fairy dust" and similarly "angel dust" are slang terms for drugs, keeping that idea of a change in perception. References and Further Reading

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed