|

In “Cupid and Psyche” and “East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon”, the heroine breaks a taboo, loses her husband, and has to travel the world and complete daunting tasks to find him - but she does eventually win him back.

In “Beauty and the Beast,” Beauty returns home to visit her family, but stays too long (forgetting the Beast's instructions and thus breaking a taboo). The Beast nearly dies due to her absence, but she returns just in time to swear her love. This revives him and breaks his curse. But there are a couple of versions that don’t end so happily. One is “The Ram,” a French literary tale by Madame D’Aulnoy (1697). This story resonates with many different fairy tales. Returning from war, a king greets his three daughters and asks about the color of their dresses. The first two say that the color represents their joy at his return, but the youngest, Merveilleuse, chose her dress because it looked the best on her; the king is displeased, calling her vain. Then he asks about their latest dreams. The first two dreamed he brought them gifts, but the youngest dreamed he held a basin for her to wash her hands. The king is furious at the idea he would become her servant (ATU 725, "The Dream" - like the Biblical story of Joseph). He decides to get rid of her (“Love Like Salt”, “King Lear”). He orders the captain of the guard to kill her and bring back her heart and tongue; instead, the captain warns her to flee and brings back the heart and tongue of her pet dog (“Snow White”). Bereft, Merveilleuse travels until she discovers a splendid kingdom inhabited by sheep, ruled over by a royal ram. The Ram explains that he is a human king, cursed after he refused to marry a wicked fairy (“Beauty and the Beast”). But the time limit of his curse will soon run out, so if Merveilleuse just hangs in there a little while, she’s guaranteed a handsome king husband. She also gets to ride in the Ram's pumpkin coach ("Cinderella"). Eventually they hear that Merveilleuse's sister is to be married; the Ram agrees that Merveilleuse should attend the wedding, but asks her to return afterwards. She attends the wedding in splendor, amazing the king and courtiers who don't recognize her, before returning home (shades of “Cinderella” again). Similarly, she attends her second sister's wedding. This time, the king catches her and offers her a basin of water to wash her hands; her dream has come true. Recognizing her, he repents of his wrongdoing and makes her the new queen. Meanwhile, the Ram begins to fear that Merveilleuse has left him. He runs to her father's palace, but the guards - knowing that he will take Merveilleuse away - refuse to let him in. When Merveilleuse finally steps outside, she finds him lying dead of a broken heart, and is stricken with grief and guilt. The end. (A depressing and very racist intro, in which the heroine’s slave girl and pets foolishly sacrifice themselves in an attempt to help her, sets up for the tale’s eventual tragic ending.) D'Aulnoy's story was fairly well-known and was translated into other languages for both children and adults. Some English translations go further and have Merveilleuse die at the end, too (possibly due to mistranslation - in D’Aulnoy’s version, we may assume Merveilleuse reigns on her own as queen). Others alter it to have a happy ending; Sabine Baring-Gould, for instance, introduces the plot point that the Ram must sit in a king’s throne and drink from a king's cup to break his curse, and the heroine (renamed Miranda) is able to gain this favor during her reconciliation with her father. This turns the story on its head, making the family reunion the solution to the problem rather than the issue that breaks the couple apart. There is also a Portuguese tale, “The Maiden and the Beast," which runs much more like the familiar "Beauty and the Beast." Rather than a rose, Daughter-No.-3 requests "a slice of roach off a green meadow". A roach is a fish, so she’s asking for an impossible thing, a fish from a grassy field. The Beast is only heard as a voice, never appearing in person. The biggest divergence is the ending. During her stay at the Beast’s castle, the girl returns home for three days for her oldest sister's wedding, then again for her next sister's wedding, and finally for the death of her father. She even takes rich gifts back with her, making the family wealthy. However, on the third visit, she is warned that her sisters will sabotage her. Sure enough, they sneakily let her oversleep and take her enchanted ring, causing her to forget everything. When she finally remembers, she rushes back to the enchanted palace and finds it deserted and dark. In the garden, she discovers a huge beast lying on the ground (the first time the Beast has appeared in person). He bitterly reproaches her for breaking his spell, and dies; the heartbroken girl dies a few days later, and the surviving sisters lose their money. It’s never mentioned what this Beast’s deal is, whether he’s a man under a curse or what. However, much like other versions of Beauty and the Beast, the context makes it clear that this is a fantasy version of an arranged marriage; the father knows full well that he is trading his daughter for the "slice of roach." The moral...? There's a prevailing theory that "Beauty and the Beast" is a moral lesson about accepting an arranged marriage and learning to see the good in an unfamiliar spouse. These tragic stories show what happens when the heroine accepts her new spouse but still fails to completely take on her new role as wife. She’s distracted by her family, who are unwilling to let her go. You could make a case that these stories are about the danger of female disobedience (and, for “The Ram”, something about the whims of fate). However, it doesn’t seem right to blame the heroines for disobedience. Merveilleuse and the maiden both fully intend to comply with the Beast character’s request. However, both are thwarted by their own innocent forgetfulness and by household members fighting to keep them home (the Maiden’s sisters interfering with her return, and Merveilleuse’s father locks the palace doors in order to keep her there, followed by the guards keeping the Ram out). It’s different from the older sisters’ jealous sabotage in “Cupid and Psyche” or “Beauty and the Beast.” In these tragic versions, the family members are, ultimately, acting out of misguided love - fearing the husband-monster-interloper, wanting to keep a beloved youngest child with them rather than let her become a married woman in a household of her own. Do you know any Beauty and the Beast stories that end tragically? Let me know in the comments! SOURCES

1 Comment

The Tyme books are a series of fairytale retellings for kids by Megan Morrison, set in a world co-created with her friend Ruth Virkus. I read all three books in one day; it was the first time in a while I’ve stayed up late reading in bed.

Grounded: The Adventures of Rapunzel is the first in the series and, naturally, a retelling of Rapunzel. The story takes the fairy tale as only a rough guideline; Rapunzel leaves her tower very early on, leading to a road trip with the male lead (Jack, of Beanstalk fame). Grounded makes a lot of storytelling choices that feel very familiar for Rapunzel retellings. I can draw lines to Disney’s Tangled (2010), Marissa Meyer’s Cress (2014), and Shannon Hale’s Rapunzel’s Revenge (2008)... especially Tangled. But it also feels fresh and new, from Morrison’s writing and from the rich and lively world Rapunzel’s exploring. Morrison’s Rapunzel starts out as bratty and spoiled, but even from the beginning she has a kind nature, and we get to watch her grow and mature. The book dives deep into her complicated relationship with the witch (the only mother she’s ever known). Rapunzel and Jack are the leads of the first book, and appear briefly in subsequent books. Disenchanted: The Trials of Cinderella is a very loose retelling, more in homages and references than in plot. The main plot is newly-rich student Ella’s fight for labor rights. Ella has a stepmother and stepsiblings, but they’re not evil; everyone means well, and both they and Ella have some growing and forgiving to do. The fairy godparents are a charitable organization who grant wishes, although they’ve lost their way over the years and Ella’s two godfathers are trying to get back to their original ideals. Glass slippers are the current fashion in the haute couture-obsessed kingdom. There’s a scene where fairy godparents fix up Ella’s gown and shoes so that she can look her best at a mandatory royal ball, and she makes an impression dancing with the prince before later leaving in a rush - but this is a fairly early segment setting us off on the grander plot. Ella's love interest Dash is a fun twist on the concept of Prince Charming; recently freed from a curse which forced him to be charming but insincere, he's a shy and reserved young man re-learning how to interact with people. In contrast to the subtle slow burn in Grounded, Dash and Ella fall fast and hard for each other, and marriage is even mentioned. I wasn’t a huge fan of this considering the age group. Where Grounded was more of a character piece and exploration of a troubled mother-daughter relationship, Disenchanted has a more wide-reaching political plot of Ella fighting against the kingdom’s corruption and the exploitation of the working class. The way everything comes together in the end is pretty fantastic. Transformed: The Perils of the Frog Prince might be my favorite of the trilogy. Remember how I mentioned plot threads and callbacks? In Grounded, Rapunzel gets a pet frog who clearly has something more going on. In Transformed, we learn that the frog is actually the missing Prince Syrah (mentioned in a throwaway line in Disenchanted). This book is a redemption arc. Syrah starts out as an arrogant, thoughtlessly cruel boy who makes a wish on the wrong wishing well and gets hit hard by karma. In a major difference from the fairy tale, frog-Syrah can’t talk, making his quest to break the curse infinitely more difficult. When a mysterious plague starts affecting people, Syrah realizes that as a tiny, overlooked frog, he might be in a unique position to investigate what’s really going on. After the first couple of books, I was expecting a romance; I was pleasantly surprised to realize that this is a very different narrative. Syrah does not get the girl, and a big part of his redemption arc is about accepting that, which I thought was a meaningful message and a good moral for young readers. And as part of that, the second half of the book becomes a buddy cop plot starring Syrah and his ex’s new boyfriend (the only person to figure out who he is and come up with a way to communicate). I loved this plot, and it’s where the story really took off. The complex themes and questions are sometimes more mature than I expected for a Middle Grade novel, and I think it’s suitable for all ages. Morrison builds an elaborate world that feels full of life and adventure (and sometimes a bit silly, like the characters in Disenchanted all having fashion-themed names). Each book is a standalone, but background events hint at more adventures elsewhere in the world and sometimes get unexpected callbacks in later books. There are tons of fairy tale references. Also, the color-themed kingdoms are all parallels to Andrew Lang’s Coloured Fairy Books series (“Cinderella” appeared in the Blue Fairy Book and Disenchanted takes place in the Blue Kingdom; “Rapunzel” was in the Red Fairy Book, and Grounded starts off in the Redlands. I love this so much!) Morrison said at one point on her blog that she planned six books. However, it looks like there hasn’t been any news since Transformed came out in 2019. I don’t know if we will ever see more of the series, which makes me sad. I would love to see Morrison’s take on Sleeping Beauty and find out where the magic acorn subplot was heading. But I'm very glad that at least these three volumes exist. If you’re looking for a fairytale retelling series with some shadow and seriousness to it alongside the quirky worldbuilding, and if you liked series like The Hero’s Guide to Saving Your Kingdom, Half Upon a Time, or (Fairly) True Tales, give these books a read. Also, while on the subject of Rapunzel, I've started a new page for variants of the Maiden in the Tower tale type. Check it out! A few months ago I reviewed The Story of the Little Merman, a gender-swapped retelling of The Little Mermaid from 1909. I've come across a few modern parallels, but by far the best recent example is one from 2023: The Silent Prince, by C. J. Brightley. The delightfully cocky mer prince Kaerius falls for a human princess named Marin whom he saved from drowning, and seeks to become human so that he can officially meet and woo her. He quickly finds himself in the middle of a complicated political situation, all while learning to be a humbler person.

This is part of the Once Upon a Prince series, released by the indie publisher Spring Song Press, which is also run by Brightley. It includes twelve books, each by a different author, which retell popular fairy tales with a focus on the male leads and often a twist to the plot. The Silent Prince owes a fair amount to Disney. The "sea witch" role is filled by a giant kraken (although not as malevolent as Ursula) and Kaerius gives up his voice, not his tongue. However, there are also some elements from Andersen; Kaerius experiences pain from dancing in tight boots that he's not used to, and the story nods to the original story's themes of self-sacrifice. I've been on a kick of reading mermaid novels for quite a while now, and found true underwater settings fairly rare, probably because they're difficult to write well. It really requires a different mindset. It's easy for underwater worldbuilding to get cheesy with ocean puns, talking fish friends, and so on. But although the novel takes place 95% on land, Brightley's merfolk feel wild and alien in a way that I've rarely seen. This novel is at its best in the worldbuilding and the scenario of a merman adjusting to land. Plenty of mermaid stories feature the mermaid character being a fish out of water, but Brightley really sinks her teeth into it - for instance, we learn that licking someone's hand is a polite greeting among merfolk, while hugging is considered a show of great vulnerability because it exposes your throat. There's an element of realism in play, as seen by Kaerius experiencing numerous health concerns when he comes ashore after inhaling water. The way that Kaerius communicates is also refreshing. In a lot of retellings, the mermaid can't communicate with the prince at all. But Kaerius is used to sign language as part of normal merfolk life, so he just naturally signs to the humans he meets, and the princess and her guards gradually start to learn enough to understand him. There are a couple of letdowns. The ending felt rushed; after such an in-depth and colorful story, this was particularly disappointing. And although we spend a lot of time with Kaerius and his character development, we never really gain a deeper understanding of Princess Marin. Kaerius does realize that his initial impression of Marin was mere infatuation, and that he needs to actually get to know her as a person. This should be a good start! But then he gets to know her fairly easily, she turns out to be a kind and noble person, and... that's it. They have a sweet and straightforward romance. She's surprisingly chill about his strange habits and some reveals that should have been shocking; it feels like we never really get to see beyond the surface with her. We honestly get to see more of Kaerius's relationship with the human guard who hosts him. Overall, I'd class this as a solid retelling, fun and with a clean romance. It jumped right to the top of my list of favorites, and I'd suggest it to anyone who enjoys retellings and developed worldbuilding. Petrus Gonsalvus, or Pedro Gonzalez, lived at the court of the French king Henri II. Gonsalvus had a condition which today would be diagnosed as hypertrichosis, causing excessive hair growth; his face was almost completely covered in hair. People who met him would have thought immediately of the wild men of medieval legend. Around age ten, he was brought to court as a kind of curiosity and pet, much like other people with physical differences at the time. This is where he grew up, was educated, and eventually married a woman named Catherine. Most of their children shared Gonsalvus’s diagnosis; so did some of their grandchildren. Their medical studies and portraits still survive today. But was there more than a scientific interest to Gonsalvus's story? Were he and his wife the original inspiration for "Beauty and the Beast?"

I have never seen Gonsalvus mentioned in any analysis of the fairy tale, which is well-known to be inspired by an ancient storytelling tradition. That's not a great sign. But the theory has been shared around a fair amount and has some traction, so it deserves a look. The most well-known English work about Gonsalvus is probably a Smithsonian Channel documentary titled "The Real Beauty and the Beast”, directed by Julian Pölsler (2014). As seen by the title, it strongly promoted the fairy tale connection. It is no longer available on any streaming services, but based on the various reviews and summaries I’ve found, it runs something like this. Pedro is brought to Henri II’s court as a feral child: kept in a cage, fed raw meat, and unable to say anything but his name. Henri II bestows an education on him, translating his name into Latin as Petrus. Petrus thrives in his new life, but Henri II’s wife, the villainous Catherine de' Medici, designs a sadistic experiment to see whether Petrus’s children will also be hairy. She marries him to one of her servant girls, also named Catherine. The bride knows nothing about her groom, and faints when she sees him for the first time at the altar. Their union ends up being a happy one as she discovers Petrus is a kind and gentle man. Still, their happiness is marred, as their children who inherit Petrus’s condition are taken away and gifted to various nobles, and even though Petrus and Catherine ultimately settle down to a quiet life in Italy, the lack of burial records is interpreted to mean that Petrus is still seen as a beast and denied the Christian rites of burial. It’s a tragic Beauty and the Beast retelling complete with the moral of looking beyond appearances and plenty of memorable dramatic details (like Catherine "fainting at the altar.") This documentary seems to have been heavily fictionalized, and does not seem like a reliable source. (Incidentally, Beauty faints at the first sight of the Beast in the 1946 film La Belle et la Bête, although not in the fairy tale. So I wonder if the filmmakers actually drew from Beauty and the Beast stories to craft their depiction of Petrus and Catherine. As we'll see in a minute, there's no historical basis for details like Catherine fainting.) The Gonzalez family in historical record We can only get at the Gonzalez family’s story by piecing together brief and scattered sources. It’s hard to pin down dates, and English studies are especially scarce. Gonsalvus was known in life as "le Sauvage du Roi" (“the King’s Savage”) or, more personally, “Don Pedro.” His name appears under many different translations; it seems like he preferred Pedro, so that's what I'm going with. He was born in Tenerife in 1537, spoke Spanish, and was probably Guanche (the indigenous people of Tenerife, enslaved by the Spaniards during conquest). It may be that he was brought straight from Tenerife by slave traders. On the other hand, Alberto Quartapelle found another account from about the same time of a hirsute ten-year-old shown off throughout Spain by his father; given the rarity of the condition, it’s possible that this was Pedro, and that his own father showed him off and eventually gave or sold him to the French king. What is generally agreed on is that Henry II wanted to prove that a “savage” could be transformed into a gentleman. He arranged for Pedro to live like other noble children of court and receive a royal education. He chose important officials as Pedro’s tutors and caretakers. As he grew older, Pedro served at the king’s table, a small but still prestigious task with a salary and personal access to the monarch. After Henri II's death in 1559, his widow the regent Catherine de'Medici became Pedro’s main patron. She probably did either arrange his marriage or, at the very least, promise financial support (she arranged marriages for her court dwarfs). In Paris, in 1570, Pedro married Catherine Raffelin (spelled variously as Raphelin, Rafflin, Rophelin), the daughter of Anselme Raffelin (a textile merchant) and Catherine Pecan. As part of her dowry, Catherine Raffelin brought half of an apartment on Rue Saint-Victoir, where the couple moved. We don’t know what they may have thought of each other at first or what their first meeting was like. However, Pedro’s extensive education and wealthy lifestyle would presumably have been appealing to a potential wife. Portraits of Pedro and Catherine are reminiscent of Beauty and the Beast. And not only was Catherine a merchant’s daughter just like the Beauty of the fairy tale, but it seems she was considered a lovely woman. A portrait by Joris Hoefnagel (included at the top of this post), which shows Catherine resting a hand on her husband's shoulder, was accompanied by a segment written from Pedro’s point of view (possibly even by Pedro himself?) describing Catherine as “a wife of outstanding beauty” (Wiesner 153). Merry Wiesner lists their seven children as Maddalena, Paulo, Enrico, Francesca, Antonietta (“Tognina”), Orazio, and Ercole. All three girls plus Enrico and Orazio had hypertrichosis. Ercole apparently died in infancy, with records unclear whether he was hirsute. With baptismal records, Quartapelle places their births a few years earlier than Wiesner’s estimates and gives the initial four (in French) as Francoise, Perre (Pierre?), Henri, and Charlotte. Some children were recorded more than others, which means some may have died young; alternately, the children who didn’t inherit hypertrichosis were not recorded as much. During his years in Paris, Don Pedro studied at the University of Poitiers and became a professor of canon law. He was also in frequent contact with the king, being tasked with delivering his books. Important noblemen close to the royal family served as godfathers to the Gonzalez children. However, around the 1580s or 1590s, something happened. The family began traveling and showing up in the records of various European courts. This was also the period when many of the portraits and medical studies were done. We don't know exactly when they left, but the queen's will provided for her court dwarfs and not the Gonzalezes, which might indicate that they already had a new patron by then. It's not clear exactly why this happened, but in 1589 there were a couple of significant events: the death of Catherine de'Medici and the assassination of her son Henri III (Ghadessi p. 109-110). France was full of civil and religious unrest, Henri III's death sent people into a frenzy of joy, and it was probably not the best time to be an easily-recognizable favorite of the royal family. If the Gonzalezes hadn't already left, that would have been the time to get out. They ultimately entered the patronage of Duke Alessandro Farnese and settled at his court in Parma, Italy. The children with hypertrichosis lived similarly to their father, sent as gifts to the courts of Farnese relatives and friends. Despite this disturbing note, it does seem that the family kept in contact. Most or all of them eventually moved to the small village of Capodimonte. Their sons found wives there, and Orazio occasionally commuted from there to Rome, where he held a position in the Farnese court (Wiesner, 220). Pedro is thought to have died in Capodimonte around 1618, Catherine a few years later. There’s debate over how much agency the family members had, but Roberto Zapperi argues that their son Enrico used his position wisely and pulled strings with the Farneses to make this quiet retirement possible (Stockinger, 2004). So, a couple of notes on the information floating around from the Smithsonian documentary. First, it apparently painted Catherine de’Medici as a cruel woman who treated the Gonzalez family like a science experiment. In a completely opposite take, scholar Touba Ghadessi suggests a protectiveness, honor, and perhaps even fondness in her patronage of the family. I wonder if the truth is some mixture of the two; it wasn't necessarily black and white, and there could have been both fondness and rampant exploitation. Oddly enough, Catherine de' Medici had a little bit in common with the Gonzalezes. She, too, was foreign, and her enemies described her as monstrous. And the Gonzalezes ultimately settled in her homeland of Italy. As for the burial thing: the fact that we don't have burial records for Pedro doesn't really mean anything. The records are so spotty that it's not even clear what all of his kids' names were. Furthermore, we have baptismal and burial records for some of his children who shared his condition. I don't believe he was "denied a Christian burial" or anything like that. The inherent contradiction is seen in the fact that Pedro was married. However... it’s true that in spite of gaining some privileges - pursuing his studies, finding a wife, settling down in a quiet home - Pedro was never fully free. He was taken from his childhood home and possibly even shown off around Spain by his own father. He and his children lived their lives being othered and commodified by those around them, viewed as curiosities and entertainment. And societal attitudes towards him and his family show in the family portraits, where Gonsalvus and his children wear courtly dress but are juxtaposed against caves and wild scenes befitting animals. The fairy tale of "Beauty and the Beast" The story that we know today as “Beauty and the Beast” is not a folktale, but a literary fairy tale, originating with Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve’s Beauty and the Beast (1740). This was a fantasy novella following conventions of the time, full of vivid descriptions and convoluted subplots. It took clear inspiration from folktales of beastly bridegrooms. The earliest written examples of this tradition are “Cupid and Psyche” (Rome, 2nd century AD) and “The Enchanted Brahman's Son” (India, ~3rd-5th centuries AD). People in Pedro and Catherine's time might have read Straparola's "The Pig King" from the 1550s. Closer to home for Barbot, there was D'Aulnoy's "The Ram" (1697) and Bignon's "Princess Zeineb and the Leopard" (1712-1714). Because "Beauty and the Beast" is literary, created by a single author, it’s far more likely to contain specific references or traceable inspirations than an oral folktale would be. So, was Pedro Gonzalez one of Barbot's influences? Well… it's not clear if Barbot would have known who Gonzalez was. The family's personal history has only regained attention since the 20th century, with researchers like Italian historian Roberto Zapperi doing a lot of the work to piece together the details. The family’s legacy seems more associated with Austria than with France. Their portraits in Ambras Castle in modern-day Austria remained famous, even leading to the name "Ambras Syndrome" for a type of hypertrichosis. But an inventory of the Ambras Castle collection listed Gonzalez as “der rauch man zu Munichen”, or “the hirsute man from Munich,” because that’s where the portraits were painted (Hertel, 4). Meanwhile, in France: in 1569, author Marin Liberge could make reference to “the King’s Savage” expecting that his audience would know who he meant (Amples discours de ce qui c'est faict et passe au siege de Poictiers). But by the late 19th century, French researchers were absolutely baffled by this cryptic description, not connecting it to the portraits at all. One researcher in 1895 was on the right track with the idea that Don Pedro was some type of entertainer, but also noted that his memory simply isn’t well preserved in historical records, and questioned how well-known he actually was (Babinet 143-145). When Barbot was writing in 1740, a hundred and fifty years after Gonzalez's heyday in Paris, how well was he remembered? Did Barbot ever hear of the Ambras Castle collection? Even if she did, how much would she learn of Catherine - who was only in the portraits as Gonzalez's anonymous wife? In fact, Barbot’s novel features several vivid descriptions of the Beast, and he doesn't look anything like Pedro Gonzalez. He is covered in scales, with an elephant-like trunk. This Beast seems more influenced by stories of snake husbands - like the two oldest recorded versions of beastly bridegroom tales. Psyche fears that her husband is a serpent or dragon (although Cupid never actually appears this way in the story), and the Enchanted Brahman’s Son is a snake. With the lack of parallels and number of differences, it seems unlikely that Gonzalez inspired this. A few years later, Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont wrote a shorter, child-friendly adaptation of “Beauty and the Beast” which became pretty much the canon version. In her version, the Beast is barely described. This gave illustrators the freedom to imagine their own interpretations. You’ll find images of the Beast as an elephant, bear, wild boar, lion, or walrus. Depictions leaned more towards large, hairy beasts associated with strength and fearsomeness. In the era of adaptation and illustration, the Beast is more likely to be some kind of bipedal chimera. This leads up to the most iconic film portrayal: Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film La Belle et la Bête with its leonine Beast. The resemblance between the Gonzalez portraits and Cocteau’s Beast in his extravagant ruff and doublet is so striking that it seems likely the makeup artist, Hagop Arakelian, drew inspiration from Pedro Gonzalez (Hamburger, pp. 60-61). Similarly, Disney artist Don Hahn recalled the Gonzalez portraits as "one of many sources of inspiration" during early design stages for the 1991 animated film Beauty and the Beast (Burchard, 173). So, did the author of Beauty and the Beast take inspiration from Pedro Gonzalez and his wife Catherine? Probably not; there's nothing to indicate that she did, and a few things to point against it. But did later artists? Possibly! Fairy tales are archetypal, resonating with universal morals and fears. Trying to attribute a fairy tale to a real person's biography is dangerous ground. But sometimes real people do get adopted into storytelling tradition, and what's more, real events can have parallels to fairy tales. Sometimes, there really is a hairy nobleman who marries a merchant's beautiful daughter. We know very little about Pedro and Catherine Gonzalez; we don't know whether they had a romance for the ages. But their story is worth remembering, and I hope scholars are able to uncover more about them. SOURCES

Further Reading Last month I reviewed "The Story of the Little Merman" by Ethel Reader. This story received a new print edition in 1979, but when it was originally released in 1909, it was part of a volume with a second story, "The Queen of the Gnomes and the True Prince," also illustrated by Frank Cheyne Papé. This one was apparently never re-released, although the 1979 edition of "The Little Merman" still contains Reader's original foreword with references to it. Luckily, I was able to track down a 1909 edition. Having enjoyed "The Little Merman," I was eager to see what the companion story had to offer; however, unfortunately, this ended up being where the cracks begin to show.

The story begins with a king and queen having a baby daughter. At her christening, they fail to invite a certain old witch. The witch, angered, curses her so that she will spend her life underground in the realm of the gnomes. A good fairy, however, adds that a prince will come to rescue her. After some years, the witch's machinations ensure that the young princess is lured out of her protected castle and whisked away to the gnome realm. The gnomes are all men, having worked their wives to death. The gnome king intends to marry the princess. She sees the humans they have carried off to be their slaves in the mines, and meets the king's son: a good-natured, mischievous imp known as the Goblin. As the princess grows up underground, waiting for her prince to slay the guardian dragon and free her, she becomes close friends with the Goblin. He works on her behalf, trying to find her prince for her, but the princes who arrive never quite measure up. (One of the story's funniest moments is when a tough, imposing he-man of a prince sees the dragon and immediately, sheepishly leaves.) Finally the Goblin takes matters into his own hands and faces the dragon. He's badly wounded, but manages to kill it so that the princess and all the enslaved humans can escape. When the princess kisses him, her love transforms him into a handsome prince and they return home to rule her kingdom. The Goblin is a pretty delightful hero, and I enjoyed his gradual development from seeking other princes to saying "Fine, I'll do it myself." I was honestly sad when all the magic went away at the end - gnomes transmuted into ordinary humans, dragons into mundane animals, and the Goblin into a handsome prince (although he keeps his quirky personality). This story feels in many ways like "The Story of the Little Merman." They are written to mimic and deconstruct classic fairytales, and they have a very specific Edwardian feel. There's the same whimsical, tongue-in-cheek style. There is a princess waiting for a prince to save her and her people. There is an unconventional hero who takes up the role, faces the dragon, and nearly gives his life in the process. It's not as clearly linked to any particular fairy tale; there are, of course, shades of "Sleeping Beauty," and dragon-slayer tales, and maybe - maybe - George MacDonald's The Princess and the Goblin. However, it never reaches the same level as The Little Merman. Many of the same themes are here, but it doesn't have the same examination of morality and self-sacrifice. On the one hand, I had a much deeper appreciation for the Merman story after studying "The Little Mermaid." On the other hand, only one of these stories got a reprint, so maybe editors agreed with me. Both stories rely deeply on the tropes of the dragon-slayer and the damsel in distress, although with faint twists. These dragon-slayers get beaten within an inch of their life. And the damsels get their own moments to shine - the Merman's princess when she cares for the Merman's wounds and then dives into legal matters and uses her political education to save him, and the Queen of the Gnomes when she cares for the Goblin's wounds and... actually that's pretty much it. That's the issue. You see the Merman's princess trying to work against her circumstances herself and the way her love for her people inspires the Merman. The Queen of the Gnomes shares these traits - kindness, generosity, patience, the impulse to help the disadvantaged - but it feels like a slightly subpar repeat. We get a sense of the Merman's princess's rage and frustration when she is blocked from helping her people. There is a key moment where, as a child, she tries to stand up to her uncle and is consequently sent away. She doesn't return until much later in the book. In contrast, the Queen of the Gnomes is centered in her story, so we stay with her perspective the whole time, and she doesn't really do anything. She just waits. Both stories are subversive. (Note, in particular, the plotline of the wicked goblins, who are shamed by the narrative for wearing down their wives with endless housework, while the Goblin, our hero, is willing to pitch in with chores like dishwashing.) The Merman and the Goblin are intriguing heroes. They're sensitive and gentle. They are explicitly described as not traditionally attractive, and they step in when the more traditional hero types fail to show up. But they're both still born to royalty, and that is in large part why they get the princess. Gardeners' sons and mailmen need not apply, even if they are kind or brave or childhood friends of the princess. It doesn't stand out so much if you only read one story, but reading them back-to-back, it starts to form a pattern. (For comparison, in The Princess and the Goblin series, the princess eventually marries a miner. That was published in 1872.) There is some meta commentary throughout The Queen of the Gnomes, even more than in The Little Merman. They need a prince to slay the dragon because that's what happens in this kind of story. The princess waits because that's what the story demands. The Goblin knows that he is not a traditional prince and that this means the dragon may just kill him. But while reading The Queen of the Gnomes, I was definitely wishing the meta could stretch a little farther and get a little more creative. Maybe because The Little Merman set me up to expect just slightly more. Overall, The Little Merman is a stronger story. Although it's not perfect, it has a deeper examination of its themes. The Queen of the Gnomes feels a little like a retread or an early draft of the same plot. I'm excited to say that Writing in Margins made it onto Feedspot's Top 45 Fairy Tale Blogs!

A while back, I discovered that an author named Ethel Reader had written a gender-swapped retelling of "The Little Mermaid" all the way back in 1909. Well, actually there are a lot of other elements mixed in. The story The novella begins by introducing the undersea kingdom of the Mer-People. In the kingdom is the Garden of the Red Flowers; a flower blooms and an ethereal, triumphant music plays whenever a Mer-Person gains a soul. The Little Merman, the main character, is drawn to the land from a young age. One day he meets a human Princess on the beach, and they quickly become friends. The Princess eventually explains that her kingdom is plagued by two dragons. She is an orphan, and the kingdom is ruled by her uncle, the Regent, until the day when a Prince will come to slay the dragons and marry her. The Little Merman wants increasingly to have legs and a soul like a human; there’s a sequence where he goes into town on crutches and ends up buying some soles (the shoe version). However, after some years, the Princess tries to take action about the dragons and protect her people. The Regent, who is actually a wicked and power-hungry magician, sends her away to school. The Little Merman asks her to marry him, but she explains that "I can't marry you without a soul, because I might lose mine" (p. 52). The Little Merman plays her a farewell song on the harp. The Little Merman talks to the Mer-Father, an old merman who explains that he once gained legs and went on land to marry a shepherdess whom he loved. However, when he made the mistake of revealing who he really was, the humans were terrified and drove him out. Unable to find a soul, he returned to the sea. The Mer-Father tells the Little Merman how to get to an underground cave, where he will meet a blacksmith who can give him legs. He gives him a coral token; as long as he keeps it with him, he can return to the sea and become a merman again. The Little Merman goes to the blacksmith, who happens to be a dwarf living under a mountain. He pays with gems from under the sea, and the blacksmith cuts off the Merman’s tail to replace it with human legs. The Little Merman wakes up on the beach, human and equipped with armor and weapons. The Mer-Father has also sent him a magical horse from the sea. He proceeds to the castle, where people assume he is one of the princes there to fight the dragon and compete for the Princess’s hand. The Princess, now eighteen years old, has just returned from college. The Princess doesn’t acknowledge the Little Merman—who is going by the name “the Sea-Prince”—and he’s afraid to identify himself after the Mer-Father’s story of being cast out. Every June 21st the Dragon of the Rocks appears and people try to appease it with offerings of treasure; every December 21st the same thing happens with the Dragon of the Lake. The princes go out to fight the Dragon of the Rocks, but it vanishes through a solid wall of the mountain; they all give up in disgust except for the Little Merman, who has been spending time with the Princess and now shares her righteous fury on her people’s behalf. With help from the dwarf blacksmith, he finds a way into the dragon's lair and slays it. The people adore him, while the resentful Regent spreads rumors against him, and the Little Merman is secretly disappointed that he hasn’t earned a soul. In December, the Little Merman goes out to fight the Dragon of the Lake. It drags him underwater, but he can still breathe underwater, and slays it too. The wedding is announced, but the Little Merman is conflicted; he still doesn’t have a soul, and if the Princess marries him, she will lose hers. He also fends off an assassination attempt from the Regent, but saves the Regent's life. The next morning, the Little Merman announces to the people that he is from the sea and has no soul. The Princess always knew it was him and loves him anyway, but everyone else rejects him and the Regent orders him thrown in prison. After a trial, he will be burned to death. The Princess gets the trial delayed and begins studying the royal library's law books. The Merman waits in jail, only to hear the Mer-People calling to him. They offer to break him out of jail with a tidal wave, but he refuses, worried about the humans. The Dwarf Blacksmith also offers him an escape, reminding him that he won’t get a soul either way; the Merman refuses again. Then the Little Merman's loyal human Squire visits. He has raised an army from the countryfolk, with the Sea-People and the Dwarfs also offering to fight. It may be bloody, but if they win, the Little Merman will have a chance to earn a soul. The Little Merman vehemently refuses; he will not kill his enemy, and he knows the kind of collateral damage that the Sea-People and the Dwarfs will bring to the kingdom. He gives the Squire his coral token, telling him to take it back to the Mer-Father; he is not returning to the sea. Alone in his cell, waiting for death, he hears the music that means a merperson has won a soul. The next day is the trial, where the Regent accuses the Little Merman of deception and treason. The Princess speaks up in his defense. The only issue is that the Little Merman doesn’t have a soul, so she reveals that she has found a record of a man from the Sea-People who came on land, was similarly accused of having no soul, and asked how he could get one. A local Wise Man told him that he would only win a soul when the Wise Man’s dry staff blossomed; at that moment, the staff put out flowers. The judge and lawyers decide to try this out, the Regent gleefully offers his staff, and the staff blossoms. The shocked Regent confesses all his crimes, including that he was the one who brought the dragons. The Little Merman intervenes to spare him from execution. The Little Merman and the Princess get married and rule the kingdom well, and there is a new red flower in the underwater garden. Background and Inspiration The Story of the Little Merman was initially released in 1907; it was a novella, with the same volume including an additional novella, The Story of the Queen of the Gnomes and the True Prince. Both were illustrated by Frank Cheyne Papé. The Story of the Little Merman was reprinted on its own in 1979. I have been unable to find much information about Ethel Reader, or any books by her other than this. In the dedication, she describes herself as the maiden aunt to a girl named Frances. The story itself has many literary allusions. It’s maybe twee at times but also had a lot of really funny lines. The overall mood made me think of George MacDonald’s writing. Some quotes that stuck with me:

First and most prominently, “The Story of the Little Merman” is an allusion to “The Little Mermaid.” Not only is the title similar, there is the description of the Garden of the Red Flowers, paralleling the Little Mermaid’s garden. There is also the overall plotline of the merman longing for both his human love and an immortal soul, going through a painful ordeal to become human, and winning a soul through self-sacrifice - with a final moral test where his loved ones beg him to save himself by sacrificing everything he's been fighting for. (One distinction: The Little Mermaid just gets the chance at an immortal soul, while the Little Merman actually gets his soul, along with a happily-ever-after with the Princess.) That's about where the similarities end. Reader’s book adds elements of dragon-slayer stories, and - most prominently - it plays on Matthew Arnold’s merman poems. “The Forsaken Merman” (1849) is one I recognized. Related to the Danish ballad of Agnete and the Merman, it tells of a merman who has taken a human wife and has children with her. The human woman hears the church bells and wishes to go back to land for Easter Mass: “I lose my poor soul, Merman! here with thee.” Once there, she never returns, leaving her husband and children forlorn. “The Neckan” (1853/1869) was new to me. This poem also deals with a human/sea-creature romance and the question of souls and religion. The Neckan takes a human wife, but she weeps that she does not have a Christian husband. So he goes on land, but when he introduces himself, humans fear and revile him. This is directly based on a Danish folktale, collected in Benjamin Thorpe's Northern Mythology: A priest riding one evening over a bridge, heard the most delightful tones of a stringed instrument, and, on looking round, saw a young man, naked to the waist, sitting on the surface of the water, with a red cap and yellow locks… He saw that it was the Neck, and in his zeal addressed him thus : “Why dost thou so joyously strike thy harp ? Sooner shall this dried cane that I hold in my hand grow green and flower, than thou shalt obtain salvation.” Thereupon the unhappy musician cast down his harp, and sat bitterly weeping on the water. The priest then turned his horse, and con tinued his course. But lo ! before he had ridden far, he observed that green shoots and leaves, mingled with most beautiful flowers, had sprung from his old staff. This seemed to him a sign from heaven… He therefore hastened back to the mournful Neck, showed him the green, flowery staff, and said : " Behold ! now my old staff is grown green and flowery like a young branch in a rose garden ; so likewise may hope bloom in the hearts of all created beings ; for their Redeemer liveth ! " Comforted by these words, the Neck again took his harp, the joyous tones of which resounded along the shore the whole livelong night (1851, p. 80) Arnold edited his poem after its first publication. In his first version, the priest rejects the Neckan and that’s it. In his second version, Arnold reintroduces the theme of the miraculous flowering staff. However, instead of being overjoyed like the Neck in the folktale, Arnold's Neckan continues to weep at the cruelty of human souls. The flowering staff is an old and widespread trope; it appears in the biblical story of Aaron, in a legend about St. Joseph, and most similarly in the medieval legend of Tannhauser, where a knight asks a priest if his soul can still be saved after he dallied in an underground fairy realm. While The Story of the Little Merman is clearly influenced by Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” it is equally or more inspired by “The Neckan,” even directly quoting it in one scene. I have never been a fan of the motif that merfolk don’t have souls, but it was an accepted idea in medieval legend. I recently read Poul Anderson’s The Merman’s Children, inspired by the story of Agnete and the Merman and thus distantly related to The Story of the Little Merman. In Anderson’s book, receiving souls is a Borg-like assimilation that costs the merfolk their old identities and memories. It’s a bitter take on the conflict between Christianity and paganism. Reader has a much more positive view on merfolk gaining souls. The merfolk are beautiful, but they just kind of exist, doing no harm and no good. They and other supernatural beings are part of nature. The Little Merman comes truly alive through his time on land, learning passion and emotions, and how to care about people other than himself. He learns how to feel anger and hatred, but these can be positive, the story explains—anger on behalf of vulnerable people, hatred of evil and greed. I like how the story raises the question of how the Merman actually acquired his soul. Did he earn a soul in the moment that he selflessly faced death and sent away his last chance of escape, or was his soul developing all along from the moment when he first saw land? The story hints pretty strongly that it’s the second one. I also really like the play on the Little Mermaid's final choice in Andersen's original. Here, this scene is greatly extended and really delves into the alternatives, raising different possibilities - might the Little Merman return to his old existence, or might he take a moral step back but then continue with his quest for a soul afterwards? He's not willing to do either. Whereas the Little Mermaid has to decide whether to harm her beloved who has hurt her deeply, the Little Merman is urged to kill a mortal enemy who has tried to murder him multiple times. He rejects this partly out of a sense of honor - he has killed dragons but he will not sink to the Regent's level by murdering a human - and partly because he foresees the bloodshed that this kind of war would bring to the whole kingdom. (In the illustrations, the Little Merman wears a crown - possibly of kelp - that looks a little like a crown of thorns.) It's also interesting to contrast the romance with that in The Little Mermaid. Here, the Merman and the Princess are childhood friends. They reconnect as young adults and their relationship deepens. The Merman is inspired by the Princess’s fierce love for her people. He does not have the Little Mermaid’s quest of marrying in order to get a soul; instead he is trying to get a soul so that he can marry the Princess. It’s his concern for her well-being that causes him to reveal his identity and give the chance for her to back out of their mandated engagement, even though it nearly costs him his life. The Little Merman has some fun fish-out-of-water moments and reads as a very peaceful, innocent character. There is a touch of realism in the fact that he gets beat up pretty badly in both dragon-battles and needs a lot of time to recover on both occasions. Meanwhile, the Princess is brave, loyal, and intelligent. She may not ride out to fight the dragons herself, but she’s the one who saves the Merman in the end, using her political savvy and education to delay his trial and build a legal defense. This book is chock-full of folkloric and literary references, and I think I might even prefer its take on souls to that of The Little Mermaid. Bibliography

This review contains spoilers - marked towards the end.

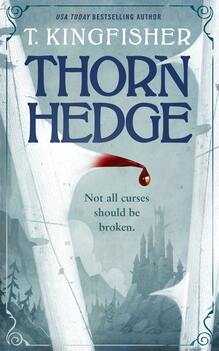

I recently reviewed Thornhedge by T. Kingfisher, which combined the Sleeping Beauty story with legends of changelings. Not long after reading that one, I picked up a very different changeling tale in Unseelie by Ivelisse Housman (2023). The story picks up with Iselia ("Seelie"), a changeling adopted by humans and raised as sisters with her human counterpart Isolde. The two girls live on the road, working as pickpockets after a disaster with Seelie's uncontrollable magic forced them to flee their home. (Where Kingfisher's Toadling is an adult caretaker to her changeling counterpart thanks to time shenanigans, Seelie and Isolde are equals, twins. Their relationship is loving but tumultuous.) Then they stumble upon another two thieves mid-heist, and Seelie winds up with a curse imprinted on her skin, taking the form of a magical compass pointing the way to a long-lost treasure. The groups reluctantly team up to find the treasure, even as Seelie realizes that she'll have to face her dreaded magic and learn to control it. This is Housman's debut novel and it's a decent read, although it feels a little clumsy or muddy at times. The romance takes a while to get going but eventually won me over, and I kind of liked that approach. It is the first in a duology, and ends in an unresolved cliffhanger. However, I was very intrigued by Housman's take on changelings. Housman's novel is woven from two modern ideas surrounding changelings: a recently-created short story that has arguably achieved folktale status, and the theory that changelings were inspired by children with autism. Housman, who is autistic, wrote Seelie inspired by her own experience: "I think a lot of autistic people grow up feeling like we’re from another world, and the idea of putting a positive spin on that feeling within a magical world like the ones I grew up reading was irresistible" (Kirichanskaya, 2023). The changeling as twin is a growing trope, which has done a lot of its growing within Internet culture. (The name 'changeling' can apply to either a stolen human child or its fairy replacement, but in this post I will mainly use it to refer to the fae child.) Thornhedge feels more indicative of the older changeling tales, where faeries are dangerous and changelings are monsters; the story is told from the perspective of the stolen human child. In folktales, changelings might look like babies or disabled children, but many weren't babies at all. They could be pieces of wood, or adult fairies. The reveal of the changeling's true nature often emphasizes its extreme old age. In one Cornish tale, a changeling named Tredrill posing as an infant turns out to have a wife and children of his own (Bottrell, Traditions and Hearthside Stories, pp. 201-202). In a parallel story from Iceland, a changeling in the shape of a four-year-old boy is startled into admitting that he's really a bearded old man and "the father of eighteen elves." In one Danish folktale, "How to Distinguish a Changeling," a father wakes up just in time to stop a changeling swap, but finds himself holding two babies with no way to tell which is his. The family ends up putting the babies through an extremely dangerous test by exposing them to a wild stallion, causing the fairy parent to take back her child (Thorpe, Northern Mythology, vol ii, pp. 175-176). However, moving into the 20th century, more authors started to write stories that treated changelings as children rather than monsters. The first instance I can find of a story where a human family decided to raise both their own child and the changeling is the short original fairy tale "The fishwife and the changeling" by Winifred Finlay (Folk Tales from Moor and Mountain, 1969). Here, the fishwife makes a bargain with the faerie mother—give back her child, and she'll willingly care for and nurse the faerie baby, no trickery needed. The faerie child grows up to consider the humans his true family. Other sympathetic portrayals of changelings became popular. The Moorchild by Eloise Jarvis McGraw (1996) was an influential children's book told from the perspective of a changeling who grows up feeling like an outsider. Holly Black's Tithe (2002) has a teenaged girl discover that she is a changeling. Later in the series, she rescues her human counterpart (still a young child thanks to her time in fairyland), taking the roles of older and younger sisters. In Delia Sherman's Changeling (2006), the human child raised in a fairy realm must work together with her changeling counterpart who's more accustomed to mundane human life, with both returning to their adopted homes at the end. In An Artificial Night by Seanan McGuire (2010), the main character accepts her changeling double as her sister (although the swap takes place when the characters are adults). But the idea of the changeling and human child raised together as twins feels more specific. After Finlay's story, the next "adopted changeling twin" story that I know of appears in The Darkest Part of the Forest (2015) by Holly Black (again). In a key part of the backstory, a woman turns the faeries' games back on them. She burns the faerie baby with a poker to summon the faeries to return her son. However, then she announces with righteous fury that she will also keep the faerie baby: “You can’t have him,” said Carter’s mother, passing her own baby to her sister and picking up iron filings and red berries and salt, protection against the faerie woman’s magic. “If you were willing to trade him away, even for an hour, then you don’t deserve him. I’ll keep them both to raise as my own..." Not long afterwards and along the same lines - but with different logic behind it - in March 2017, the Tumblr blog magic-and-moonlit-wings posted a very short story titled "Rescue and Adoption," published on Tumblr (March 2017). The story starts in medias res inside a fairy mound. The fairies present a woman with two perfectly identical babies and give her a choice. One is her own, and the other is the changeling she's been raising. She startles them with her declaration that both are her children, one biological and one adopted, and returns home with both babies. The premise is reminiscent of the Danish folktale, with a family left trying to identify their true child after fairy trickery, but the message is diametrically opposed. The woman rejects the fairies' game and lovingly accepts both children. "Rescue and Adoption" went somewhat viral. Many people wrote their own spins with the original author's blessing. An abbreviated version was posted as a writing prompt on Reddit (March 2022) and on Tumblr (April 2022), leading to even more reimaginings. (Here is one example, an untitled story by Tumblr user Dycefic, which begins with a childless woman being told to plant a pear tree in a manner reminiscent of "Thumbelina" or "Tatterhood".) The number of retellings and adaptations make this a modern folktale in its own right. There is an echo of the same sentiment in the middle-grade book Changeling by William Ritter (2019). Here, as in the Danish folktale, a parent interrupts the changeling switch just in time, but is left with two babies and no way to tell which is which. However, although other people in the village are fearful of the changeling and suggest dangerous tests, she decides to care for both as her own. But Housman's book is even more directly inspired by the "Rescue and Adoption" tale. As previously mentioned, it is also built on the theory that changeling tales were inspired by children with autism, which was circulating on Tumblr around the same time. See, for instance, this group discussion circa 2016. The short story "here's a story about changelings" (posted August 2019) is a realistic tale about autistic children growing up in a world where the only name for them is "changelings." Out of works already mentioned here, Delia Sherman's Changeling and dycefic's take on the "Rescue and Adoption" prompt both nod to this theory by featuring changeling children with autistic traits. There may be some truth to the autism theory, and there are some compelling parallels. In traditional stories, the changeling is detected when a healthy, beautiful baby undergoes an apparent change in personality and a regression in hitting typical milestones - similar to some autism diagnoses. But I would argue that the legend came from a mix of many different factors: disabilities, failure to thrive, postpartum depression, and/or chronic illness. See the tragic case of Bridget Cleary: when she fell ill in 1895, her husband murdered her, claiming that he was trying to retrieve his real wife. In 1643, a folk healer and accused witch named Margaret Dickson was unable to heal a sickly child. She then told the mother to throw it onto the fire because "the bairne was not hirs." The mother opted not to take Dickson's advice, and the child apparently recovered (Scottish Fairy Belief: A History, pg. 97). Martin Luther encountered a disabled child that he believed was a changeling and child of the devil. As far as I'm concerned, the changeling myth is the darkest fairy tale, because at least some people believed in it and acted on it. In some cases, it may have been a cautionary tale warning people not to leave children unattended. But in others, it was an excuse for societally-sanctioned neglect and murder. (Major spoilers from this point on) So far, Unseelie falls in line with many other takes on the "Rescue and Adoption" tale. However, a deft twist towards the end casts the whole story—and modern changeling tropes in general—in a different light. The mother in Unseelie is absent, but the story of her long-ago rescue of her children underlies the entire plot. Much like the mother in Kingfisher's Thornhedge, she is courageous and determined and loving—but maybe that's not enough. Housman stated in an interview, "I approached this story with the intention to take the changeling myth, turn it upside down, and reclaim it—all through the lens of a fantasy world... All that to say, changelings in this world are autistic people, and vice versa" (Creadan, 2023). Towards the end of Unseelie, it is revealed that Seelie was the original human child, and her neurotypical sister Isolde was the duplicate created by the fairies. (Housman also includes the more modern idea that the changeling swap can leave the mortal child with magical abilities of their own.) Seelie's mother assumed that she was a changeling, and thus went to the fairies and demanded her "original" daughter back. The malicious fairies were happy to play along, producing Isolde. Seelie's mother still behaved admirably by accepting both children and thwarting the fairies' cruel game, but is it enough to make up for her inherent rejection of a daughter who didn't match her expectations? We'll see where the second book in the duology takes things. Housman's followup, Unending, is expected to be published in 2025. Bibliography

A while ago, I spent several blog posts reviewing historical figures who have been put forward as the "real Snow White" - both of which turned out to be marketing campaigns with only the flimsiest of connections. Anastasia provides a look at something like the opposite. The real story of Anastasia Romanova is short, brutal and heartbreaking, but it’s been used as the basis for a fairy tale.

On July 17, 1918, the Russian imperial family was executed by Bolshevik revolutionaries. This included the Tsar Nicholas II, his wife the Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, and their children Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei, along with members of their entourage. Their executioners mutilated the bodies and buried them in the woods. Afterwards, the Bolsheviks announced Nicholas's death, but they covered up the deaths of his family and spread misinformation about them. This added fuel to the persistent idea that some might have survived. Numerous impostors appeared claiming to be surviving members of the imperial family who had escaped. The most famous, by far, was Anna Anderson. The Anna Anderson Timeline 1920: An unknown young woman is admitted to a mental hospital after a suicide attempt. Eventually, she begins claiming to be one of the Romanov princesses—initially Tatiana but then Anastasia. By 1922, she has come to the attention of Romanov supporters, friends and surviving relatives, and is using the name Anna (short for Anastasia). Some of the relatives denounce her as a fraud, but others embrace her. Despite her troubled and erratic behavior, and the fact that an investigation in 1927 points to her actually being a missing Polish factory worker named Franziska Schanzkowska, Anna becomes extremely famous. Supporters provide enough money for her to live comfortably. Adopting the surname Anderson, she's introduced to high society in America. Anderson’s story inspires numerous media adaptations, whether movies or stage or books. Some of these adaptations accept her claims; others draw more nuanced portraits that don’t settle on whether or not they believe her. 1928: The silent film Clothes Make the Woman, loosely inspired by Anna Anderson, depicts Princess Anastasia escaping the Bolsheviks with the help of a sympathetic revolutionary and coming to America. 1953: Marcelle Maurette writes a play called Anastasia, in which a team of conmen decide to use an amnesiac woman, "Anna," to fake the return of Princess Anastasia and swindle her grandmother, the Grand Duchess. But Anna might actually be Anastasia. The question never gets a definitive yes-or-no answer. In an ending twist, she falls in love and runs away to lead a normal life. 1956: Ingrid Bergman stars in Anastasia, a film adaptation of Maurette's play. The same year also sees a German film, The Story of Anastasia. 1979: An amateur sleuth discovers the mass grave of the Romanovs, although further investigation is impossible due to the Soviets. 1984: Anna Anderson dies of pneumonia in the U.S. 1991: Collapse of the Soviet Union. DNA analysis confirms that the bodies in the mass grave are those of the Romanovs. However, Alexei and one of the girls (either Maria or Anastasia) are unaccounted for. Tests of Anna Anderson's DNA prove that she was not a Romanov and strongly indicate that she was Franziska Schanzkowska. So after all the debate, all the bitter argument and broken relationships among supporters and opponents, “Anna” is finally proven a fraud . . . but the two missing bodies still leave room for the idea of a surviving Romanov. 1997: Don Bluth's animated film Anastasia loosely adapts the 1956 Ingrid Bergman movie (which, remember, was an adaptation of the 1953 play). This version is straightforwardly marketed as a fairy tale, departing from historical facts in favor of something more Disneyfied. Anastasia is eight instead of seventeen when her family dies, and instead of a Bolshevik revolution, we get Rasputin as an undead wizard who sparks the fall of the Romanovs through black magic and has a talking bat for a sidekick. The lost princess, suffering from amnesia, grows up in an orphanage as "Anya" until she is scooped up by two shysters who see her as an ideal candidate for their scam. One of them—Dimitri—falls for her while gradually realizing that she really is the true Anastasia. Anya reclaims her identity, reunites with her grandmother, and defeats Rasputin, but decides to elope with Dimitri. Other animated Anastasia films mimicked this fairy tale style (two knockoffs, by Golden Films and UAV Entertainment, also came out in 1997). 2007: The last two Romanov bodies are located, and further DNA testing confirms their identities. Some people still try to challenge this or cling to the idea that some of the Romanovs escaped, but at this point it's clear that the entire family died that night in 1918. Exploring the implications Why was it Anastasia, and not any of her siblings, who inspired such fervor? It wasn’t even clear whether the missing body was Anastasia’s or Maria’s. And there were definitely impostors posing as other surviving Romanovs. The name "Anastasia" means "resurrection," which is a romantic coincidence... but the real reason may be much more mundane. It was Anna Anderson. She was more famous than any of the other impostors. And notably, she was originally supposed to be Tatiana. That idea quickly fell apart, partly because she was the wrong height. But whose height matched? Anastasia's. And so Franziska Schanzkowska found her new identity, and Anastasia is now the central figure of a myth because her height matched up with a scammer's. Somehow this makes it feel even more deeply sad. With Don Bluth’s film, a new fairy tale really took shape. And it wasn't the story of Anastasia. It was the story of Anna Anderson—the myth that she and her supporters created around herself, of a lost princess regaining her memories. Maurette's play, and its many derivatives (the 1956 film, Don Bluth's film) tell the narrative of crooks coaching a woman to play the part of Anastasia. This is exactly what detractors accused Anderson and her supporters of. The real story of Anastasia Romanova is a life cut short by brutal violence. Anna Anderson’s fairy tale, by contrast, is romantic and enjoyable. It relies on a very old and widespread trope: the random orphan who discovers that they’re the long-lost heir to the kingdom. Herodotus told a story like this about Cyrus the Great being raised by a shepherd. It's in the story of King Arthur. It's in the Italian fairy tale “The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.” It’s in Madame D'Aulnoy’s fairy tale “The Bee and the Orange Tree” and in the original, highly convoluted "Beauty and the Beast" by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve. It’s Shasta in The Horse and His Boy and Cinder in The Lunar Chronicles. It’s Disney’s Briar Rose and Hercules and Rapunzel (and, oddly enough, also the Barbie version of Rapunzel from 2002). (One unusual touch of the Anastasia myth is that the princess is a little older when she vanishes - not an infant - and amnesia is a lot more likely to be in play.) What's especially interesting is the way the story may have evolved since the graves and DNA tests. In the Maurette-verse of Anastasia stories, Anastasia may discover her true identity, but she ultimately chooses to leave behind the prestige of princesshood and its obsession with the past for a normal life with the man she loves. These stories are typically colored by the real-world context that there is no kingdom for her to go back to, that things have changed too much. What inspired this post was noticing the number of Anastasia retellings out there. I read two of them around the same time a couple of years ago--Heart of Iron by Ashley Poston (2018) and Last of Her Name by Jessica Khoury (2019), both of which are sci-fi retellings of the Anastasia myth set in space. Poston’s book draws a lot from the Don Bluth cartoon. The heroine goes by Ana and her love interest is named Dimitri. The villain has a name similar to Rasputin. There's a pivotal moment where Ana must prove her identity to her grandmother. However, the Maurette-inspired "fraud" plot is played way down, barely a factor at all. Khoury's book takes more of its creative spark from history. As Khoury said in an interview, "what if instead of ending the Anastasia story ... a DNA test was the beginning of her tale?" So it begins with the heroine, Stacia, being spotted as the lost princess via a genetic scan, and having to go on the run. Both of these new stories move away from Maurette's plotline of is-it-or-isn't-it fraud. Instead they focus on the Anastasia figure fighting to take back her kingdom and queenship. It’s much more the fairy tale brand. A 2020 film, Anastasia: Once Upon a Time, is sort of the same animal. It includes supernatural elements and evokes a fairy tale setting with its title. It heavily features Rasputin as an antagonist but features a different setup, following Anastasia traveling through time to befriend a modern-day girl. The ending allows Anastasia and her family to escape and survive, but that is an endnote, not the main plot. These are works written in a time when we know that the Romanovs died and any other alternative is a fantasy. We know that "Anna Anderson" and all the other supposed survivors were frauds. Most people reading these books probably don't even think of the individual person Anna Anderson at all. The mystery has been solved, but the myth endures. BIBLIOGRAPHY

(This review contains spoilers.)

A retelling of Sleeping Beauty. Toadling, a changeling child raised by water monsters known as greenteeth, has grown into a strange-looking being with a propensity for turning into a toad. She is sent back to the human realm to a small kingdom, to attend the baby princess's christening and bestow a blessing on her. Two hundred years later, Toadling guards what's left of the castle inside a protective hedge of thorns, containing the threat within, until one day a kindhearted knight rides up, searching for the legendary sleeping princess. This was a short read - I finished it in an hour. I enjoyed it a lot (I've enjoyed all of T. Kingfisher's books that I've read). It's nice to read books about unabashedly good and kind heroes. Toadling's relationship with Halim is very sweet. There are also lots of references to fairy lore. (My favorite section was a brief exploration of the idea that fairies steal milk from cows.) The main idea of the novel is the changeling myth. Toadling is actually the true child of the king and queen, having grown up in the fairy realm where time doesn't match up with ours. And the princess, Fayette, is her fae counterpart—a juvenile version of the cruel, heartless fairies who will vaporize humans without a second thought. The older Fayette gets, the more dangerous she becomes. The most heartbreaking part is the character of the queen, who loves her daughter fiercely and does her best to protect Fayette while also coming to realize that Fayette is a monster who must be stopped. She never suspects her real relationship to Toadling, who never breathes a word. There is no grand resolution for her character. It's pretty bleak. In the afterword, Kingfisher explains that she had the idea while working on Harriet the Invincible, also a fractured fairy tale retelling of Sleeping Beauty (in which the princess is an indomitable hamster, cursed to prick her finger on a hamster wheel on her twelfth birthday, who fights back against the curse and visits some other fairy tales). If you're looking for a short and sweet retelling of Sleeping Beauty, definitely give this one a read. Years ago, I wrote a blog post on the inspirations behind Hans Christian Andersen's "Thumbelina" (1835), examining a theory that the characters were influenced by people Andersen knew. And then I wrote another one a few years after that, focusing on the imagery of tiny flower fairies, which plays a big role in this fairytale. I want to revisit it this topic again and explore a little more deeply. It's always interesting to get into Andersen's writing process because these have become such classic fairytales and there are many different aspects to his stories. "The Little Mermaid," for instance, can be read as a semi-autobiographical tale of unrequited love, but also as Andersen's response to the hyper-popular mermaid story Undine, and also taking influence from other mermaid tales and tropes.