|

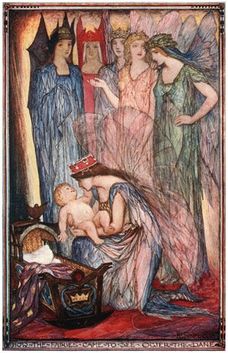

Those strange, benevolent fairies who show up to give advice or magical artifacts. When did they start to appear in fairy tales? How many people have them? What are their powers? Where did they come from? Let's start with the most well-known - Sleeping Beauty's and Cinderella's. Fairies attend Sleeping Beauty's christening and give her gifts such as beauty and a sweet singing voice. An angry fairy, however, dispenses a curse. The most famous is Cinderella's fairy godmother, who appears with magical clothing and a coach just when Cinderella needs them. Both of these stories with their attendant fairies were first published by Charles Perrault in 1697. The older Sleeping Beauty story, Sun, Moon and Talia, had no fairies or magic. As for Cinderella, the Grimms' Aschenputtel had the heroine aided by the ghost of her dead mother. The Chinese Ye Xian has the ghost of a pet fish which was originally a guardian spirit sent by her deceased mother, and the Scottish Rashin-Coatie has a red calf. There are plenty of tales where the hero is aided by a fairy or other magical creature, but Charles Perrault and probably also Madame D'Aulnoy popularized the fairy godmother. In 1697, they both put out books of fairytales in which such beings were heavily featured. D’Aulnoy wrote "Finette Cendron," "Princess Rosette," and "Princess Mayblossom," as well as “The Blue Bird” and “The White Doe,” where the villain has a fairy godmother. The trope of the fairy godmother became more and more common during the era of literary French tales such as "Prince Fatal and Prince Fortune" or "Princess Camion" (1743), where they typically show up at births and give prophecies. The relationship reflects a Catholic environment. In medieval times, the godparents served an important role in the child's life, including their religious education. Although fairy godmothers didn't become a widespread thing until Perrault and D'Aulnoy, their roots do go back into legends and myth. In medieval romances, the "fays" frequently preside over births and give out gifts and prophecies.  Red Romance Book by Andrew Lang. “How the Fairies Came to See Ogier the Dane.” Red Romance Book by Andrew Lang. “How the Fairies Came to See Ogier the Dane.” Six fays arrive to bestow heroic qualities on the newborn Ogier the Dane. The final one, Morgain picks him as her future husband. A similar scene, also with Morgain, appears in the Enfances Garin de Montglane. In the 13th century Huon de Bordeaux, Oberon was cursed by a fairy at his christening. In the stories of Merlin, a man named Dionas is the godson of the goddess Diane. Diane gives his daughter Niniane a destiny as a great sorceress. In 1621, Tom Thumb has "the Queene of Fayres" as "his kind Midwife, & good Godmother." She helps at his birth, and throughout his life provides him with magical aid and tools - including fancy clothing and impractical footwear. Marian Roalfe Cox collected 345 variants of Cinderella. In her collection, fairy godmothers appear in Peau d'ane (Perrault 1697), Finette Aschenbrodel (1845), the Russian Zamarashka (1860), Hubac's Peau d'Ane (1874), Baissac's Story of Peau d'Ane (1888), Catarina (1892), and The White Goat. In the Basque tale of Ass'-Skin (1877), there is a human godmother who gives the heroine advice. In both "Marie Robe de Bois" and "Le Pays des Brides" (1892), the heroine has a "sorceress-godmother." In "The Young Countess and the Water-Nymph" (1852), a water-nymph agrees to stand godmother to the child of her friend the countess. In "Ditu Migniulellu" (1881), the word godmother is not used, but fairies do show up at the girl's birth to dispense gifts, and one returns to help her get to the ball. In "Terra Camina" (1892), there is a christening and a godmother with magical powers. However, it's hard to tell whether she's a fairy or not. The Estonian tale of Rebuliina (1895) describes the christening in detail. The godmother is mysterious and is never identified, but clearly has magical powers. There are countless stories where fairies aid the heroine, but the ones I've mentioned are specifically godmothers or have a connection to the heroine beginning at her birth. These magical godmothers are not like typical fairies, which are not creatures you would want around your newborn baby. Indeed, many types of fairies and spirits flee church bells and would never be seen at a christening. They're more likely to steal an infant than bless it, and babies aren't safe until they've been baptized. In contrast, fairy godmothers are wise women, typically benevolent, focused only on furthering their godchild's lot in life. (They still have a capacity for evil, as seen with Oberon or Sleeping Beauty.) When the Cinderella figure is aided by the ghost of her mother, it has a hint of ancestor-worship. In a different direction, I think there's a version where Buddha steps in. Fairy godmothers, who preside over births and prophesy the newborn's fate, are descended from the Fates of mythology - like the Roman Parcae, Greek Mourae, and Norse Norns. The Mourae appear shortly after Meleager's birth to prophesy his death. The Prose Edda says that besides the three main norns Urd, Skuld and Verdandi, "there are yet more norns, namely those who come to every man when he is born, to shape his life". There are other mythologies featuring similar figures. Pi-Hsia Yüan-Chün was a Chinese goddess of childbirth; she had two attendants, one of whom brought children and the other who gave them good eyesight. Latvian folklore tells of a birth goddess named Lauma, and fairies known as Laumė that foretell a newborn's future. The Albanian Fatit or Miren, butterfly-riding fairies, approach the cradle three days after the baby's birth to determine its fate. The story of the fairy godmother puts these myths into a Christian context. It formalizes the relationship between the child and the spirit overseeing her birth, and brings them closer together, explaining why the fairy's so invested. Going from the other direction, it plays up godparents. The godmother steps in for the deceased mother and provides guidance, but this approach turns her from a mere advice-giver into an incredibly powerful guardian. I haven't found anything on fairy godfathers. Well, except Godfather Death, a very different kind of story, where a very different mythical being takes the role of godparent.

0 Comments

My next blog post will be up on Monday, but this YouTube video just popped up and I found it pretty relevant to my subject. Enjoy. Snow White must be a popular name in Fairytale Land. There's:

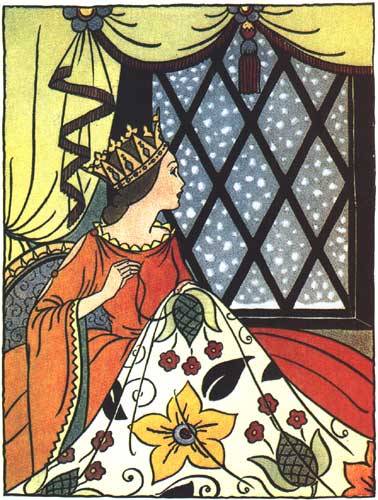

Of course, the most well-known Snow White is the one with the dwarves, and she gets her name in an unusual scene. While sewing, a queen pricks her finger and drops of her blood fall onto the snow. She remarks, “Would that I had a child as white as snow, as red as blood, and as black as the wood of the window-frame.” The resulting child is Snow White. This scene appears often in other fairytales. The Grimms also collected a Cinderella variant, beginning “A beautiful Countess had a rose in one hand and a snowball in the other, and wished for a child as red as the rose, and as white as the snow. God grants her wish.” In a Snow White variant, a count and countess are driving in the countryside. They pass three heaps of white snow, three pits full of blood, and three black ravens. What the pits of blood were doing there I have no idea. In this tale it is the husband who wishes for a girl “white as snow, red as blood, and with hair as black as the ravens,” and she instantly appears. The jealous countess tries to get rid of her, which segues into the more well-known Snow White story. In A Hundred and One Nights from North Africa (not to be confused with A Thousand and One Nights), King Sulayman ibn ‘Abd al-Malik sees two ravens fighting in his courtyard. This causes him to wonder, “Did God ever create a girl with skin as white as this marble, with hair as black as those ravens and with cheeks as red as their blood on the marble floor?” (The answer is yes. He finds her.) Similar incidents with a dying black-feathered bird against white marble or snow appear in “The Crow" (from Italy), "La princesse aux trois couleurs" (from Brittany) and "The Snow, the Crow and the Blood" (from Ireland). In "The King of Spain and the English Milord" from Italy, there's a maiden "as white as ricotta and rosy as a rose." In the Italian tale of “The Three Citrons,” a prince cuts his hand slicing ricotta cheese and decides he wants a wife “exactly as white and red as that cheese tinged with blood.” When trying to capture a fairy, he finds a girl as white as milk and red as a strawberry, and then a girl "as tender and white as curds and whey, with a streak of red on her face that made her look like an Abruzzo ham or a Nola salami." Not making that up. It’s strange that these violent scenes move the character’s mind to human beauty. The emphasis is on the colors being so so vivid, beautiful and significant that they cause this kind of reaction. Red represents life and passion, and white represents purity. Black is mentioned less often and is left out of some stories, but can represent death. These are the most significant colors in folklore and in some languages, and also in the early history of clothing dye. Some writers connect them to a Maiden/Mother/Crone Triple Goddess. The focus of the red blood with the pure white color can have sexual connotations and makes most analyses lean towards a girl going through her menstrual period or losing her virginity. But the colors aren’t just feminine. Although it's much rarer, they can be gender-neutral. In The Juniper Tree, a mother wishes, “ah, if I had but a child as red as blood and as white as snow.” She then gives birth to a son. In the Irish legend “Deirdre and the Fate of the Sons of Usnach,” Deirdre declares, "I can love only a man with those three colors: cheeks red as blood, hair black as a raven, and body white as snow." In the Italian tale "Pome and Peel," a young nobleman is as white as an apple's flesh, and his foster-brother is red and white like an apple peel. (Red, white and black are thematic colors throughout the tale.) These three colors were the marks of idealized beauty in many European countries, seen in descriptions throughout plays and Renaissance poetry. In Arabian poetry, the colors were for men or women. In one poem, the ideal man has “cheeks beautiful as a red rose on lily-white.” And according to another piece: “That woman is beautiful who possesses three white qualities, three black, three red; white body, teeth and the white of the eyes; black hair, eyebrows, and pupils; red lips, cheeks and gums.” The red and white coloration marks the person as beautiful and healthy. They are fair-skinned and unblemished, meaning they are upper class and don't work outside much, but not sickly pale. That poetry example lays out exactly what is supposed to be red and what is supposed to be white. The standard of beauty is someone with nice skin, clear eyes and healthy teeth. Sources

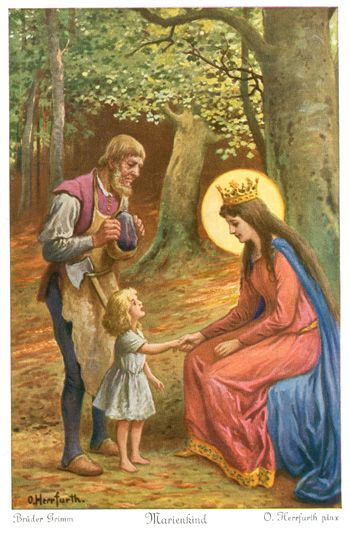

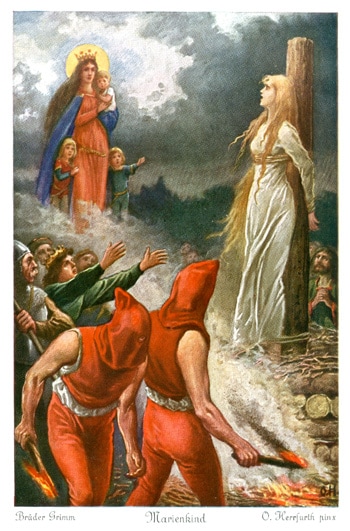

Bluebeard is a nobleman with unnerving facial hair who has been married many times. He leaves on a journey, leaving his new bride with the keys to the house and a warning not to open one particular door. Overcome by curiosity, she opens the door, only to find the corpses of all his previous wives. She gets blood on the key, which cannot be washed off. Bluebeard sees the key when he returns, realizes she's seen his murder room, and flies into a rage. He's about to kill her and add her to the collection when her relatives arrive, just in time to save the day. The story was first published by Perrault, who gave two morals. One: Curiosity bad. Specifically, female curiosity. "Curiosity, in spite of its appeal, often leads to deep regret. To the displeasure of many a maiden, its enjoyment is short lived." Two: husbands don't murder people anymore, so you should obey them without questions (like why you keep hearing bloodcurdling screams from the basement). "Fitcher's Bird," published by the Grimms, takes a different spin on the tale. The bride is given an egg, but because of her foresight, she doesn't get blood on it and tip off her sorcerer-husband. Instead she resurrects and rescues the previous wives, escapes in disguise, and has the sorcerer executed. Here, curiosity isn't bad at all, as long as you don't get caught. If you go in the exact opposite direction, you get "Our Lady's Child." This is a very different tale type, but has the same motif of the forbidden door. Fitcher's Bird absolves the curious heroine; Our Lady's Child demonizes her. The Virgin Mary - yes, that Virgin Mary - fills the role of Bluebeard and, later, the evil mother-in-law who takes the heroine's children, causes the heroine to be suspected of cannibalism, and almost gets her burned at the stake. (The theological implications often just get weird when religious figures pop up in fairytales. There are quite a few where the Devil shows up in a generic tricksy magical troll role. Holy or unholy figures turn out to have quite mundane lives, like a story featuring the Devil's granny.) "Our Lady's Child" begins with Mary offering to adopt the daughter of a poor couple. The little girl grows up in Heaven, leading an idyllic life. One day Mary goes on a journey and leaves her with the key. Behind the forbidden door, the girl sees the Trinity in all its glory, but touching the light causes her finger to turn gold. Upon her return, Mary instantly spots her hand and casts her out of heaven. The girl, who refuses to admit she opened the door, is stricken mute and survives in the wilderness for years, until a king finds her and marries her. Then Mary takes away her children as they're born, trying again and again to get the heroine to tell the truth. The heroine doesn't give in until she's arrested for infanticide and is about to be executed; then she confesses, Mary appears, and her children and her voice are returned. Mary delivers a moral about asking for forgiveness. All is well. Mary's inclusion turns the story from a horror tale into a straightforward morality piece. Some critics have defended Bluebeard because, after all, the real crime is snooping. (Not, say, murdering people and hanging up their bodies like curtains.) Unlike Bluebeard, Mary is irreproachable, and this puts the focus on the heroine's wrongdoing. The blood that stains the key or egg is a reminder of the husband's crimes. The indelible golden mark on the girl's finger is a reminder that she has trespassed on something holy. She's guilty of sacrilege. Despite the moral of asking for forgiveness, it seems odd that Mary takes roles that are traditionally so villainous. When she does these things, it drives home the message that the girl’s behavior is truly reprehensible, wholly deserving of brutal punishments. (I'm reminded of "King Thrushbeard," which also delivers disturbing levels of retribution on its heroine, in that case for mocking her suitors.) Handing the girl the key to the forbidden door is a test. Bruno Bettelheim suggests that Bluebeard feels a constant need to test his wife's fidelity, and the bloody key is a sexual symbol indicating she has strayed. We don't know exactly why Mary tests the girl's obedience. It does have echoes of the story of Eden and man's fall from grace, particularly when the girl initially tries to hide her wrongdoing and is cast into the wilderness. Had she refrained from opening the door, the reward would presumably been great. Since she does open it, and then lies about it, the punishment is equally great. Mary's actions are presented as justified. You really, really shouldn't snoop, kids, because the only place that leads is being executed for infanticide. Further Reading

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed