|

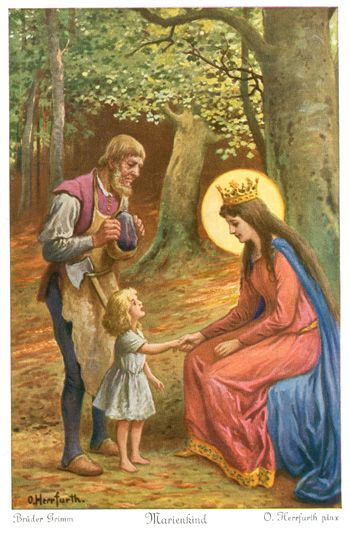

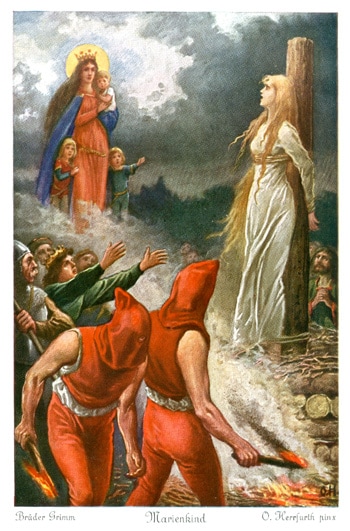

Bluebeard is a nobleman with unnerving facial hair who has been married many times. He leaves on a journey, leaving his new bride with the keys to the house and a warning not to open one particular door. Overcome by curiosity, she opens the door, only to find the corpses of all his previous wives. She gets blood on the key, which cannot be washed off. Bluebeard sees the key when he returns, realizes she's seen his murder room, and flies into a rage. He's about to kill her and add her to the collection when her relatives arrive, just in time to save the day. The story was first published by Perrault, who gave two morals. One: Curiosity bad. Specifically, female curiosity. "Curiosity, in spite of its appeal, often leads to deep regret. To the displeasure of many a maiden, its enjoyment is short lived." Two: husbands don't murder people anymore, so you should obey them without questions (like why you keep hearing bloodcurdling screams from the basement). "Fitcher's Bird," published by the Grimms, takes a different spin on the tale. The bride is given an egg, but because of her foresight, she doesn't get blood on it and tip off her sorcerer-husband. Instead she resurrects and rescues the previous wives, escapes in disguise, and has the sorcerer executed. Here, curiosity isn't bad at all, as long as you don't get caught. If you go in the exact opposite direction, you get "Our Lady's Child." This is a very different tale type, but has the same motif of the forbidden door. Fitcher's Bird absolves the curious heroine; Our Lady's Child demonizes her. The Virgin Mary - yes, that Virgin Mary - fills the role of Bluebeard and, later, the evil mother-in-law who takes the heroine's children, causes the heroine to be suspected of cannibalism, and almost gets her burned at the stake. (The theological implications often just get weird when religious figures pop up in fairytales. There are quite a few where the Devil shows up in a generic tricksy magical troll role. Holy or unholy figures turn out to have quite mundane lives, like a story featuring the Devil's granny.) "Our Lady's Child" begins with Mary offering to adopt the daughter of a poor couple. The little girl grows up in Heaven, leading an idyllic life. One day Mary goes on a journey and leaves her with the key. Behind the forbidden door, the girl sees the Trinity in all its glory, but touching the light causes her finger to turn gold. Upon her return, Mary instantly spots her hand and casts her out of heaven. The girl, who refuses to admit she opened the door, is stricken mute and survives in the wilderness for years, until a king finds her and marries her. Then Mary takes away her children as they're born, trying again and again to get the heroine to tell the truth. The heroine doesn't give in until she's arrested for infanticide and is about to be executed; then she confesses, Mary appears, and her children and her voice are returned. Mary delivers a moral about asking for forgiveness. All is well. Mary's inclusion turns the story from a horror tale into a straightforward morality piece. Some critics have defended Bluebeard because, after all, the real crime is snooping. (Not, say, murdering people and hanging up their bodies like curtains.) Unlike Bluebeard, Mary is irreproachable, and this puts the focus on the heroine's wrongdoing. The blood that stains the key or egg is a reminder of the husband's crimes. The indelible golden mark on the girl's finger is a reminder that she has trespassed on something holy. She's guilty of sacrilege. Despite the moral of asking for forgiveness, it seems odd that Mary takes roles that are traditionally so villainous. When she does these things, it drives home the message that the girl’s behavior is truly reprehensible, wholly deserving of brutal punishments. (I'm reminded of "King Thrushbeard," which also delivers disturbing levels of retribution on its heroine, in that case for mocking her suitors.) Handing the girl the key to the forbidden door is a test. Bruno Bettelheim suggests that Bluebeard feels a constant need to test his wife's fidelity, and the bloody key is a sexual symbol indicating she has strayed. We don't know exactly why Mary tests the girl's obedience. It does have echoes of the story of Eden and man's fall from grace, particularly when the girl initially tries to hide her wrongdoing and is cast into the wilderness. Had she refrained from opening the door, the reward would presumably been great. Since she does open it, and then lies about it, the punishment is equally great. Mary's actions are presented as justified. You really, really shouldn't snoop, kids, because the only place that leads is being executed for infanticide. Further Reading

Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed