|

"Don't thank the fairies"

Yet another thing that I see frequently in fantasy books and online discussion is that people should never thank fairies. It breaks fairy etiquette, or it places you in their power. But . . . where did this idea come from? Really, why shouldn't you thank a fairy? Two words: Yallery Brown. In her Dictionary of Fairies, Katharine Briggs made much of the idea of not thanking fairies as part of their etiquette. For instance, under good manners she wrote, "A polite tongue as well as an incurious eye is an important asset in any adventure among FAIRIES. There is one caution, however: certain fairies do not like to be thanked. It is against etiquette. No fault can be found with a bow or a curtsy, and all questions should be politely answered." I have previously mentioned how influential Briggs' work has been to modern fantasy. Briggs' evidence is the tale of Yallery Brown, originally published by M. C. Balfour in an 1891 article "Legends Of The Cars," in Folk-Lore vol. II. Joseph Jacobs wrote a version in plainer English. As the tale goes, a boy named Tom rescues a tiny old man the size of a baby, with brown skin and silky golden hair and beard. The grateful sprite tells Tom that he may call him "Yallery Brown," and promises him a reward - but warns Tom with a strange spark of anger never to thank him. From then on, Tom's chores do themselves, but the reward soon turns sour, as his fellow workmen find their own work ruined and turn against him, believing he's some kind of witch. Fired from his job, Tom tells the sprite "I'll thank thee to leave me alone." At those words, a cackling Yallery Brown curses him forever after to a life of bad luck and failure. Yallery Brown remains mysterious. He is clearly malevolent, with even his "blessing" truly a disguised curse, but it is never explained why thanking him is significant, or why it angers him enough that he will warn a human against doing so. Briggs drew the conclusion that explicit thanks were just not okay in fairy etiquette. Gratitude and appreciation are fine and dandy. Take, for instance, a man who mended a fairy's baking peel. The grateful fairies left him a cake. Eating it, he announced that it was "proper good" and bid "Goodnight" to the unseen fairies. He then "prospered ever after." Explicit thanks, though, is bad. For some reason. I’ve occasionally come across the theory that thanks is acknowledgement of debt, and it’s never a good idea to be indebted to the fae. Morgan Daimler's Fairies: A Guide to the Celtic Fair Folk is one example of a work that mentions this theory. This is a handy explanation, but does not explain Yallery Brown’s fierce opposition to being thanked. It’s true he is quick to repay a favor, supporting the idea he doesn’t want to be indebted to Tom. But still, why would he be angry about someone else owing him a debt? He seems pleased to have Tom within his power. Looking for analogues, we run into problems. The story of Yallery Brown is strangely unique. Usually, other fairies do not show the same repulsion to the words "thank you." For isntance, in the Swedish tale of "The Troll Labor," a troll paid a woman in silver, and "thanked her," although his specific words aren't given. Back to Yallery Brown and Balfour. Some doubt has been cast on the traditionality of Balfour's work. Balfour didn't just transcribe her tales, but gave them a literary flair. That, and the striking uniqueness of her stories, have drawn suspicion by later scholars. The English folktale collector Joseph Jacobs remarked that “One might almost suspect Mrs. Balfour of being the victim of a piece of invention on the part of her . . . informant. But the scrap of verse, especially in its original dialect, has such a folkish ring that it is probable he was only adapting a local legend to his own circumstances.” In the Dictionary, Briggs mentioned Balfour's stories multiple times, while also making reference to the controversy that by then had begun to swirl around Balfour's work. But this is aside from the point. Whatever the origin, Balfour's story is part of fairy mythology now. And I want to know why thanks are important in Balfour's story. Why is the term "thank you" offensive to Yallery Brown? Is there a missing piece here, a forgotten meaning? As I started looking for explanations, I realized that there's one line in the story that is usually missed, but which changes the entire outlook of the tale. Tom thanks Yallery Brown, with no ill consequences, at the beginning of the story! I only caught this on a second read. When Yallery Brown introduces himself and says that they will be friends, Tom responds "Thankee, master." Later, Tom tries to thank Yallery Brown again, this time for helping him with his work on the farm. This is when the sprite grows angry and commands that he never say those words. This changes the picture. Thanking Yallery Brown innocently for his friendship is fine. It is only thanks for work that angers him. Perhaps it is the low nature of farmwork. Perhaps it is the reversal of roles that upsets him; rather than a meek Tom who says "Thank you, Master," now Tom's message imply "Thank you, Servant." From here, there are connections to three other tale types. Closest is the famous tale of the household brownie. "Don't pay the fairies" Some classes of fairy work in human homes and help with chores. But their human hosts must be careful, for they will leave if given clothes or even the wrong sort of food. The safest bet is plain milk or porridge with butter. In the story of the Cauld Lad of Hylton, the servants behave as if clothes are a well-known way to banish unwanted spirits. Although leaving clothes is not a verbal thanks, it is an expression of gratitude that backfires. In The Elves and the Shoemaker, collected by the Brothers Grimm, the shoemaker's wife declares, "The little men have made us rich, and we really must show that we are grateful for it." (Emphasis mine.) She notices that the elves are naked and sews beautiful clothes for them. Unfortunately for her, the newly clad elves announce that they now look too fine and handsome to do manual labor, and the shoemaker loses their aid. In other cases, rather than the fae becoming too vain to serve, some find the gift infuriating. In a Lincolnshire version, a brownie gets angry that the offered shirt is made of rough hemp rather than fine linen. Alternately, the payment implied by the gift may insult the fae who have deigned to clean human homes. Or perhaps it's not an insult at all, just a signal that their term of service is over. The Highland spirit Brownie-Clod actually draws up a deal with some humans "to do their whole winter's threshing for them, on condition of getting in return an old coat and a Kilmarnock hood to which he had taken a fancy." However, his hosts put out his payment a little early, whether out of carelessness or because they're trying to be nice and forget that this is solely a business arrangement to him. Brownie-Clod takes the clothes and books it, leaving the rest of the work unfinished. (Keightley, Fairy Mythology, 396) The tale type is so widespread, with so many variations and rationalizations, that it's impossible to say what the true meaning is. Although some brownies seem gleeful, in other cases, like that of the phynnodderee, the spirit actually seems distraught that they must now leave. Lewis Spence theorized that the gift of clothes was insulting because the brownie was expecting a human sacrifice, and the clothes turned out to be only a decoy. I feel like that's a stretch. However, Gillian Edwards points out that these spirits are very frequently not just naked, but resemble hairy wild men or animals. (Hobgoblin and Sweet Puck, p. 111). The phynnodderee is a kind of satyr. Even Yallery Brown is covered in blond hair. The act of offering clothes might be read as an act of domestication. There's a patronizing feel to the actions of the shoemaker's wife, or farmer, or any human. They decide that the naked or hair-covered fae would be better off if they fit human social mores by wearing human-style clothes. Could there even be a connection to people turning their coats inside out to avoid being led astray by will o' the wisps, or protecting a baby from fairies by laying the father's clothes over the cradle? Whatever the roots of the story, the end result is always that a clumsy expression of human gratitude drives away fairy aid. "Don't interrupt the fairies" I have found one other tale type where the words "thank you" cause fairies to flee. In this story, a farmer discovers some tiny elves in his barn, threshing his wheat for him. "[T]he farmer, looking through the key-hole, saw two elves threshing lustily, now and then interrupting their work to say to each other, in the smallest falsetto voice: 'I tweat [sweat], you tweat?' The poor man, unable to contain his gratitude, incautiously thanked them through the key-hole; when the spirits, who love to work or play, 'unheard and unespied,' instantly vanished, and have never since visited that barn." (Choice Notes from Notes and Queries, 1859, p. 76) Similarly in Brand's Popular Antiquities, the farmer accidentally drives them off with the line that they've done "Quite enough! and thank ye!" Great! The fairies run away when someone thanks them. But wait - the act of thanks is not what they're running from. The storyteller in the first version explicitly states that they leave because they do not like to be watched. In addition, this is a very widespread story, and other versions are illuminating. A similar spying farmer does not thank the laboring fairies, but laughs at them with the condescending words "Well done, my little men." Again, the specific words that he uses are not the problem. The fairies leave because "fairies are offended if a mortal speaks to them." (The Folk-Lore Record, 1878) In most of the versions that I have read, there is no thanks. The farmer actually threatens the fairies, in a much more tense exchange. In “The Ungrateful Farmer" (Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies), the farmer is pleased that the pixies are doing his farmwork. He witnesses them throwing down their tools saying in exhaustion "I twit, you twit." He mistakenly believes that they have spotted him. Knowing that "once the pixies learn that they are overlooked they cease to return to that spot," he assumes they will leave, and leaps out at them bellowing angrily, "I'll twit 'ee!" Poof, no more pixies. In Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology, the farmer's anger is explained in a more straightforward way. The story is titled "The Fairy-Thieves" and the fairies are not helping with the harvest, but stealing it. When they make the declaration "I weat, you weat?", the farmer lunges at them with the words "The devil sweat ye. Let me get among ye!" In the more sinister story of "Master Meppom's Fatal Adventure," the "Pharisees" don't just vanish; they strike the farmer with their flails before disappearing, and he dies within the year. (Lower 1854) "Don't brag or boast of fairy gifts" Any misuse of fairy gifts could cost the receiver greatly, as in the story of the Fuwch Gyfeiliorn or stray cow. A man receives a fairy cow and his herds prosper, but as she grows older, he feels it's not worth keeping an elderly cow that will no longer give milk or calves. But when he tries to slaughter her for meat, she runs back to the fairy realm, taking all the herd with her. However, there was something in particular about revealing the fairy gift's origins. John Rhys, in Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx (1901), listed many versions of a tale where people are not to inform others where they got their fairy gold. For instance, a boy who was left money by the Tylwyth Teg every day, but only on the condition that he tell no one (pages 38, 83, 116, 203, 241). Generally, the tale concludes with the person telling their secret and losing the fairies' favor. The money never appears again. Occasionally, even the money they already had vanishes. In the 17th century, in Ben Johnson's Entertainment at Althorpe (1605), Queen Mab - bestowing a gift - announces, "Utter not, we you implore, Who did give it, nor wherefore: And whenever you restore Your self to us, you shall have more." The trope was around as early as the 12th-century lai of Sir Lanval, by Marie de France. In various versions from across the centuries, Lanval meets a fairy lady who becomes his lover and bestows him with wealth, gold and silver. She informs him that the more he spends, the more he shall have. However, if he ever reveals her existence, he will lose both her love and his fortune. This is more a taboo of secrecy: not to reveal the source to others. All the same, there is an overlap. It's a taboo against (public) thanks or acknowledgement. Conclusion The main theme of these tale families is that fairies like their gifts to be anonymous. They do appreciate gratitude, but they also want discretion, and they can be mysteriously picky.

If these taboos are crossed, fairy servants flee, fairy gifts melt away to nothing, and fairy sweethearts bid farewell. Not because someone used the words "thank you." That, on its own, doesn't insult the fairies' generosity. Instead, it's because a human barged in yelling at them, gave a hamhanded and offensive gift, terminated their contract, or betrayed their trust. The idea that the actual term "thank you" is offensive to fairies comes from "Yallery Brown," and nowhere else, so far as I know. The folkloric basis of Yallery Brown has been called into question, with later scholars wondering if the collector had the wool pulled over her eyes by her sources, or even if she went beyond polishing collected stories and into creating her own material. Maureen James wrote a thesis defending Balfour. At the same time, she acknowledged that many of the tales are found nowhere else. She suggested that rather than Balfour being wrong, there has been a lack of research into stories from the area of north Lincolnshire that Balfour examined. All the same, a close reading reveals that Yallery Brown does not find the words "thank you" offensive on their own. The words only become dangerous when the thanks is for his labor with farm work. Still mysterious, but it makes sense in the wider context of brownies, elves and fairies who hate to be loudly acknowledged, and who prefer subtler thanks. In fact, Yallery Brown might be a brownie. His name is Brown, after all. Edit 7/22/20: Important update! There may be more to the picture; Jacob Grimm, in Volume 4 of Teutonic Mythology, mentioned a German superstition that thanking a witch would place you in her power (p. 1800). SOURCES

9 Comments

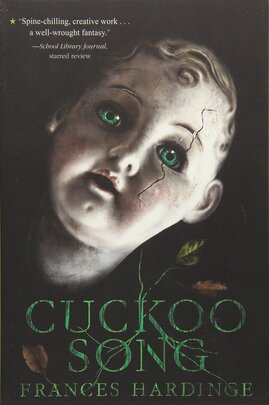

Cuckoo Song begins with a girl waking up in bed after a mysterious injury. Her memories are foggy, her own family seems unfamiliar . . . and she feels voraciously hungry, no matter how much she eats.

This children's book is set in the 1920s not long after the first World War, and centers around Triss, a young girl from a well-to-do but deeply dysfunctional family. Ever since the death of her older brother in the war, the family has been unhealthily divided and deeply miserable. And now there is something wrong with Triss. Ready for spoilers? This is a changeling story. Dark psychological horror. It's eerie, bizarre, and nightmarish, with some really beautiful prose. Many of the characters, not just Pen, are not what they seem at first. The slowly evolving friendship between Triss and her little sister Pen, for instance, was one of my favorite parts. Another character that will stay in my head for a long time is a kindly tailor, whose determination to save a lost child brings out one of the most unnerving threats in the book. The fairies in this book are bonkers. They are creepy dark fairies, but they are also modern in a way, intertwining with the technology and aesthetics of the 1920s. You can use a telephone to call the otherworld. In one scene, a child is sucked into a silent black-and-white film. Scissors actively seek to kill anything fairylike. This is the kind of book where a girl unhinges her jaw to swallow a china doll whole. It's exactly as weird as it sounds, and it works. Overall, the mood is very dark, but there was one scene towards the end of the book, in a crowded restaurant, that legitimately made me laugh out loud. I particularly love that the changeling in the book is not a fairy child replacement. I have read so many changeling fantasies where the hero turns out to be a long-lost fairy prince or princess. This changeling story is inspired by tales where the replacement is a carved piece of wood, meant to pose as a corpse and fool people into believing their loved one is dead. What would it be like to learn that you're not who you believe you are? And not even an enchanted Chosen One - nothing but a decoy? That's one plot idea I've been wishing I could read, and here it's played to its fullest extent. Personally, I am adding this to my list of favorite books. I actually stumbled on the Wikipedia summary to begin with and was kind of baffled, but when I sat down to read the book, I finished it in one sitting and thoroughly enjoyed it. If you're looking for a dark and utterly original changeling tale, featuring a sweet friendship between siblings, check this one out. You can read an interview with author Frances Hardinge on her inspirations here. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed