|

Thumbelina, or Tommelise, was first published in 1835. An author may be inspired by many things, not all of them obvious. One theory is that the character of Thumbelina was inspired by a close friend of Hans Christian's Andersen's: Hanne Henriette Wulff, known to friends as Jette (1804 -1858). Andersen considered the Wullfs close family friends. The oldest daughter of the family, Henriette was tiny, frail, and slightly hunchbacked. She became one of Andersen's most faithful penpals, and their letters are one of the main sources of information about his life. She also helped translate some of his work to English. They seem to have had a close platonic relationship, and Andersen would portray her in his autobiography as almost his muse. The theory that she inspired Thumbelina is seen in works such as Opie's Classic Fairy Tales (1974) and Houselander's Guilt (1951). Many of Andersen's fairytales were inspired by older folklore, and there was a wealth of thumbling stories that he surely drew on for Thumbelina. Tom Thumb was famous, of course; there were also the Thumbling stories of the Brothers Grimm collection, and Danish variants such as Tommeliden or Svend Tomling. Thumbelina's opening sequence, with the lonely woman longing for a child, could be straight out of one of these tales. There were plenty of other works containing tiny people which could have inspired Andersen. As listed by Diana and Jeffrey Frank, Andersen would have been familiar with Gulliver's Travels (1726), Micromégas by Voltaire (1752), and E.T.A. Hoffmann's works "Meister Floh" (1822) and "Prinzessin Brambilla" (1820). The image of a tiny girl also appeared in Andersen's previous work and first real literary success, A Journey on Foot from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager (1828). According to the Franks, there is no evidence that Thumbelina was based on Henriette. They do suggest, however, that the character of the learned but literally and metaphorically blind mole was inspired by Andersen's former teacher, Simon Meisling. Meisling was a short, overweight man who apparently did look somewhat like a mole. He repeatedly told Andersen that he would never make it as an author, calling him a stupid boy. SurLaLune also compares Thumbelina's beautiful singing voice to that of Andersen's friend, the famous singer Jenny Lind. Andersen and Lind met in 1843. In Hans Christian Andersen's Interest in Music, Gustav Hetsch and Theodore Baker assert that Lind inspired "The Nightingale," "The Angel," and "Beneath the Pillar." Another biographer, Carole Rosen, suggested in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography that Lind inspired "The Ugly Duckling" and that her rebuffing of Andersen's affections influenced the icy-hearted Snow Queen. That last one is kind of a leap. The tale that is most likely connected to Lind is "The Nightingale." The Franks mention that right after Andersen saw her perform and visited Tivoli Gardens, which had an "Asian fantasy motif," he started the Nightingale and made note of it in his diary. He finished the story in two days (pg 139). Afterwards, as Lind grew world-famous, she was known by the nickname "The Swedish Nightingale." The Franks also say that Andersen's bleak tale "The Shadow" was aimed at a friend named Edvard Collin who had snubbed him years before (pg 16). Andersen undoubtedly drew on his experiences and the people around him for inspiration. It's entirely possible that aspects of the mole were inspired by Simon Meisling, some part of Thumbelina by Henriette Wulff, or the sweet song of the Nightingale by Jenny Lind. However, a lot of that has to remain speculation.

As for more on Henriette Wulff: she loved travelling and the sea, visiting such places as Italy, the West Indies, and the United States. After her parents' death, she lived with her brother until he died of yellow fever. She returned to Denmark, but strongly considered emigrating permanently to America, where her brother was buried. In 1858, she embarked for New York on the SS Austria. Twelve days after her departure, on September 13, there was an accident with fumigation equipment, and the ship's deck burst into flames. Passengers leaped into the sea to escape the roaring fire that engulfed the entire ship. Out of the 542 people aboard, 449 perished. Henriette was among the dead. In a poem dedicated to her, a grieving Andersen called her sister. Sources

1 Comment

I have a few pages, including "The Little Folk," "List of Fairies," and "The Denham Tracts," related to fairy lore. They're a work in progress. I've found that sources are often hard to sort through. A small superstition from one area can easily bloat and transform into a supposedly famous Europe-wide tradition. Mistakes are repeated as fact until the real facts are forgotten. For one example: hyter sprites are mentioned in a few encyclopedias as small fairies with sand-colored skin and green eyes, who are protective of children and, most notably, can transform into sand martins. The most well-known source for these was Katherine Briggs' Encyclopedia of Faeries (1973), based on an account by folklorist Ruth Tongue. In 1984, Daniel Allen Rabuzzi wrote an article, “In Pursuit of Norfolk's Hyter Sprites," trying to chase down the original tradition. When he interviewed natives of Norfolk, he found no tradition of little werebird fairies. Instead, the phrase hyter, hikey or highty sprite was an idiom or nickname, most frequently used for a bogeyman ("Don't go out after dark or the hikey sprites will get you!") Everyone imagined them differently. One account described them as human-sized, batlike, threatening figures. Also, it turns out that although Ruth Tongue was a wonderful storyteller, she may have straight-up invented a lot of the stories she "collected." A class of fae similar to hyter sprites are "pillywiggins," tiny spring flower fairies in English and Welsh folklore. They have wings and antennae like insects. Though protective of their garden habitats, they are peaceful creatures who (unlike most fairies) don't bother much with humans or pranks. They live in groups, ride on bees, and their queen is named Ariel. At least, that's what you'd gather from the handful of books that mention them.

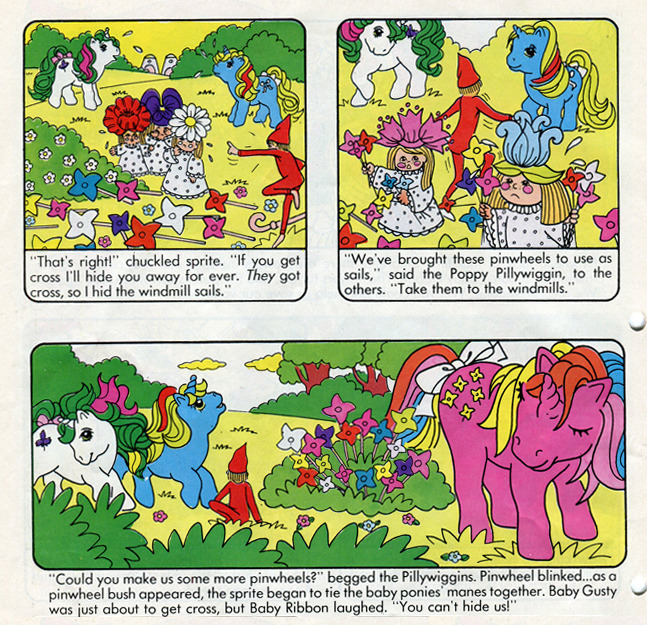

I should mention that many of these books are terrible at citations. Many of them don't cite anything, they just have one giant bibliography with no way to tell what came from where. Dubois's book is rife with misspellings, and Bane's with mistakes and misattributions. It looks like Dubois and McCoy were both elaborating on the brief description of Fairies & Elves, with very fanciful entries of their own. I have not found any supporting evidence for McCoy's "Queen Ariel." Here, McCoy actually seems to have cribbed from Shakespeare's Tempest (1610). McCoy's pillywiggins are bee-riding spring fairies, and her Queen Ariel "often rides bats, and is blonde and very seductive. She wears a thin, transparent garment of white, sleeps in a bed of cowslip, and can control the winds. She cannot speak, but communicates in beautiful song." Compare The Tempest, where a spirit named Ariel sings, Where the bee sucks, there suck I. In a cowslip’s bell I lie. There I couch when owls do cry. On the bat’s back I do fly After summer merrily. Merrily, merrily shall I live now Under the blossom that hangs on the bough. Still, later writers cited Dubois' and McCoy's work as folklore fact. Bane's encyclopedia of folklore and mythology has an entry on pillywiggins based on McCoy's description. Pillywiggin queen Ariel appears in the novels Buttercup Baby by Karen Fox (2001) and Alexander of Teagos by Paula Porter (2010). In 1986, a UK-published My Little Pony comic featured pillywiggins as non-winged flower fairies. It was apparently written for Wayne and Claire of Hanham, Bristol. There is an extensive article on pillywiggins on the French Wikipedia. But these are supposed to be English fairies - why is there more on them in French than in English? Even the talk page raises questions about this, besides pointing out that all sources are very recent and do not point to pillywiggins being a part of tradition. The most recent edit, by Tsaag Valren on June 6, 2011 says, "...after a week of research, seeing that I could find nothing more, I asked Pierre Dubois himself how he got his sources. He told me broadly that he wrote from popular English songs and discussions. As for the other works on the fairies, in general they repeat themselves: pillywiggin is the fairy of flowers, and not much more!" Although they've gained a tiny foothold into literature, I have yet to find the word pillywiggin recorded in anything before the 1970s. This is in stark contrast to other British and Welsh fairies such as pixies and brownies, which were first described hundreds of years ago, and which have variations in many different places. There could certainly be an oral tradition of pillywiggins going way back, but in that area of the world, it seems unlikely that it would have escaped notice. I can only track the name itself back to Arrowsmith's Field Guide to the Little People. It mentions pillywiggins briefly, in a list of other tiny fairies, and says they're from Dorset. My research into Dorset folklore has not yet discovered any mention of pillywiggins. Arrowsmith's bibliography lacks details, so it's hard to say where she found this information. She also mentions Ruth Tongue's hyter sprites, which as already noted, have a shaky basis in folklore. However, there are plenty of traditions of fairies being related to oak trees and plants including bluebells, thyme and foxgloves. Oak trees have magical qualities in British lore, and there's an old poem with the line "Puck is busy in these oakes." Many other plants were named for fairies. Foxgloves in particular are often connected to fairies and witches. For instance, the Welsh ellyllon are “pigmy elves” who wear foxgloves on their hands. The idea of miniature fairies goes at least as far back as the description of the one-inch-tall portunes in Gervase of Tilbury's Otia Imperiale, around the year 1210. Around 1595, A Midsummer Night's Dream gave us fairies who have power over nature, crawl into acorn cups and hang the dew in flowers. In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen's Thumbelina emerged from a flowerbud and later encountered flower spirits with fly's wings. In the first half of the 20th century, Cicely Mary Barker's illustrations and Queen Mary's interests truly popularized the idea of tiny, benevolent flower fairies. As it happens, Pillywiggin does sound a lot like another fairy name: Pigwiggin or Pigwidgeon. You might recognize this word as the name of a pet owl in the Harry Potter series. It is a name for a tiny, insignificant creature. There are lots of different theories on its etymology, but Pigwiggin became famous as the name of a fairy knight in the 1627 poem Nymphidia. From there, pigwidgeon emerged as an obscure name for a miniature fairy or dwarf. The English Parnassus (1657, Josua Poole) includes a list of Oberon and Mab's courtiers, including "Periwiggin, Periwinckle, Puck." This is based on Nymphidia with some misspellings. This textual error could be an important clue. Maybe pillywiggin, like periwiggin, is just a misspelling of Pigwiggin. From there, it was picked up by other researchers and took on a life of its own. I will say that Pillywiggin is a fun name, and I don't really mind using it for the modern flower fairy. For the moment, my search has come to an end, but I will be keeping an eye out for further clues. If you have any insight on this subject, let me know! Further reading

Part 2: What are Pillywiggins? Revisited Part 3: Pillywiggins in Pop Culture Part 4: Pillywiggins, Etymology, and ... Knitting? Part 5: Diamonds and Opals: Two Romances Featuring Pillywiggins Part 6: Pillywiggins: An Amended Theory |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed