|

A study of early Tom Thumb variants reveals a tale about a boy in weird predicaments, mostly involving pudding. He may even have been a kind of spirit or fairy originally.

However, the Japanese counterpart, Issun Boshi, is a romance: the tale of a less-than-impressive man, who manages to marry a woman far above his social stature. It's been compared to the tales of Lazy Taro (whose laziness makes him unappealing) and Ko-otoko no soshi (The Little Man, who is only about a foot tall). In Jane Kelley's Analyzing Ideology in a Japanese Fairy Tale, she goes very in-depth on modern retellings of Issun-Boshi. The hero is raised by parents who adore him even though he's tiny. He eventually falls in love with a princess, rescues her from an oni, and grows to full size with the use of the oni's magic hammer. However, the "official" version that emerges through her article may not represent the original version of the story. It's impossible to say what the original version was. There are many variants with different names. However, the Japanese Wikipedia article indicates that the original version was a little more adult. In the Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folktale (1948), the first tale listed under "Issun Boshi," the one with the longest and most detailed entry, is Mamesuke (Bean Boy). He's born from a woman’s thumb and at seventeen is only the size of a bean. He goes and finds work, and there's a scene where he hides under a wooden clog. He works for a winemaker with three daughters. To trick his way into getting a wife, he smears flour on the middle daughter’s lips while she sleeps. Thinking she's stolen his food, the family agrees that he can take her home. She tries to drown him in the bathtub, but instead of dying, he becomes a full-sized man. Everyone lives happily ever after. Another important puzzle piece is “Two Companion Booklets” in Classical Japanese Prose: An Anthology by Helen Craig McCullough (1990). In this otogi-zoshi, Issun-Boshi is born in Naniwa village in Settsu Province. (This story is full of specific details like that.) His parents are ashamed of his size (something Kelley said was un-Japanese). There are frequent poetry sections. Here, again, while seeking work, he hides under a man's clogs. When he’s sixteen and the princess is thirteen, he woos her. The wooing consists, again, of pretending she ate his rice. He leaves following his new wife as she heads towards Naniwa. Then they’re overtaken by two oni. Issun fights them off and gets a magic mallet that makes him full-size. The newlyweds go off together happy. Later, the Emperor hears the story, learns Issun is of noble heritage, and honors him greatly. These retellings indicate an older version of Issun-Boshi that was eventually toned down for children. Modern stories tend to be simpler. The trick that wins him a wife is disturbing and a little suggestive, with his accosting her in her sleep and ruining her reputation and honor - so that's gone. His parents are more affectionate, which is both softer for children and more in line with Japanese values (see Kelley). The scene where he hides under clogs is a nice illustration of his size. Buddha's crystal and other fairy stories (1908) preserves a lot of these details, including the Emperor's interest in Issun Boshi, but does not include the rice bit. There is a wealth of analysis on this Japanese site, and it's helpful even through Google Translate. The writer suggests that Issun was originally killed with the magic hammer, similar to traumatic transformations like the Frog Prince or Mamesuke. There are some interesting links between Issun Boshi and Ko-otoko no soshi. At the end, the Little Man becomes the god of Gojo shrine and his wife becomes the goddess Kannon (Tales of Tears and Laughter: Short Fiction of Medieval Japan). One of the gods of Gojo shrine is Sukuna-biko, an incredibly tiny god. As for Kannon: in most versions of Issun Boshi, she's the deity his parents ask for a son, and in some variants the princess is on her way to visit Kannon's shrine when Issun Boshi saves her.

0 Comments

The Search for the Lost Husband is a very widespread tale, closely related to Beauty and the Beast. Sometimes it seems like it's a default ending for fairy tales.

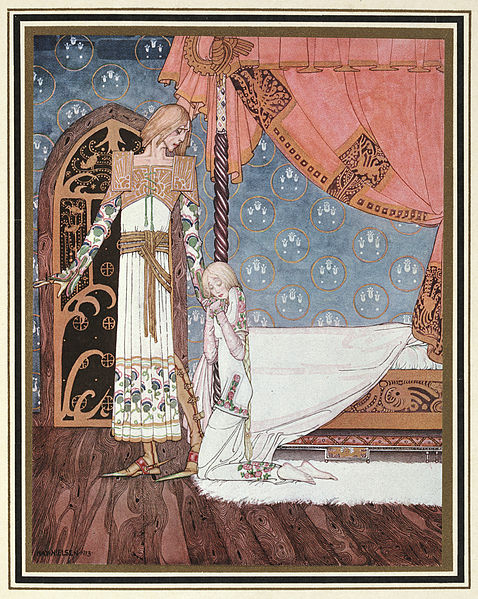

A woman marries a supernatural male being, who seems monstrous at first and might be enchanted in animal form, only appearing human at night. The wife breaks a taboo, and her husband vanishes. She then searches the world until she finds him and they are reunited. A non-exhaustive list of stories falling into this category:

The hero is a woman, and her opponent is usually a woman - an enchantress who's trapped the husband, or a rival princess who wishes to wed him. In their notes, the Grimms wax a little poetical on how the story is about the heart being tried so that "everything earthly and evil falls away in recognition of pure love." There's also an interesting note about, in this case, light being an ill omen and darkness being good. This goes back to the taboo. Often, she takes a candle and spies on her husband in the night to see his human form, or attempts to break his curse by burning his animal skin. Karen Bamford has a good analysis. The wife's journey is an act of atonement; she does penance for sinning against her divine husband, and wins him back through toil and effort. In many cases, her long journey takes her through some kind of otherworld. In an Arabic version, "The Camel Husband," the heroine goes to the land of the djinn. The land East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon is a place beyond the bounds of the physical world and the laws of nature. Psyche literally goes through hell. This quest allows her to finally truly break the spell on her husband and resurrect him from a "metaphoric death" (Bamford). In many tales, the wife visits the husband during the night, while he lies in a drugged sleep, and tries repeatedly to awaken him. In "Nix Nought Nothing," the husband falls into sleep similar to Sleeping Beauty, and only the true bride can symbolically raise him from the dead with the power of love. In Cupid and Psyche, Cupid lies wounded for quite some time. I found a Japanese folklore site that had an interesting perspective. (As seen through Google Translate, but whatever.) The groom's animal shape is the body, and his human shape represents the soul, but the soul belongs to the otherworld. Death and rebirth are required to truly bring it into the real world. So then you have stories like the "Frog King" or "The White Bride and the Black One" where the enchanted animal must be thrown against a wall or have its head cut off. There are stories where a husband seeks a lost wife; this is its own tale type, AT 420, The Quest for the Lost Bride. A couple of examples are the Russian Frog Princess, and the story of the Swan Maidens. In Household Tales, the Grimms mention "a man in a Hungarian story, whose wife has been stolen from him, seeks [help], first from the sea-king, then from the moon-king, and finally from the star-king (Molbech's Udvalgte Eventyr, No. 14)." Incidentally, Joseph Jacobs' version of the Swan Maidens also features the Land East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon, but that's from Europa's Fairy Book, in which he mashed up a lot of different traditions. Sources

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed