|

In the story of "Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp," a sorcerer convinces a young boy, Aladdin, to fetch him a magic lamp from underground cavern. Abandoned in the cave, Aladdin finds himself in possession of a magic ring that summons a genie, and of course the lamp, which summons an even more powerful genie. Aladdin falls for the local princess and orders the lamp-genie to bring her to his chambers at night, then marries her and moves into a magnificent palace built by the lamp-genie. Then the sorcerer steals the lamp back, and Aladdin must recover it. In an epilogue, the sorcerer's brother makes a try for the lamp, but Aladdin wins again. The story was an instant classic, but contains many questions about the nature of genies.

The ring and lamp don’t actually contain the genies; rather, they summon them from somewhere else, and the genies must obey whoever hold the objects. There is clearly a power hierarchy, with one genie stronger than the other. But where did they come from? Why do they serve the holder of the objects? Why a lamp? The History of Aladdin Before tackling the lamp, it's important to look at where the story came from. "Aladdin" is grouped with the stories of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights. However, there is no Arabic textual source. Aladdin did not enter the collection until the French writer Antoine Galland began publishing Les mille et une nuits, from 1704 to 1717 - the first known European translation of the Nights. The collection was a huge hit and became incredibly influential. However, Galland was working from an incomplete manuscript, and eventually ran out of stories. He went looking for new ones to insert, stories that had never been part of the collection before – including “Aladdin” and “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.” He got these from a Syrian storyteller named Hanna Diyab, in 1709. When Galland published Diyab’s stories, he never mentioned his source or gave any credit. Other genies in the Arabian Nights If you look at the older Nights, most of the djinni are free agents, not unlike fairies or other spirits in European stories. They may play matchmaker, or marry humans, or work mischief. But there are some who are imprisoned, or who serve humans. In the story "The Fisherman and the Jinni," a fisherman's nets bring up a copper bottle with Solomon's seal. When he uncaps the bottle, a djinn bursts out. We learn that he’s been in the bottle for centuries. He explains that he was one of a movement of djinn, alongside Sekhr, who rebelled against King Solomon. As punishment, this djinn was imprisoned and thrown into the sea. In the first couple of centuries, he swore to grant riches to anyone who freed him. In the third century, he swore to grant his rescuer three wishes. After four hundred years, however, he was pretty fed up and decided to grant his rescuer his preferred choice of death. King Solomon – yes, the one in the Bible – is the subject of numerous non-Biblical legends, including stories about djinn. In a Jewish legend, Solomon had a seal ring engraved with the name of God, with which he could command the spirits. One named Sekhr, Sakhr, or Asmodeus stole the ring and replaced Solomon. Solomon was forced to wander in poverty until he managed to get the ring back. Solomon's signet ring appears in other Arabian Nights tales, "The Adventures of Bulukiya" and "The City of Brass." The latter even details the war between Solomon, his army of good djinn, and an opposing army of evil djinn, which ended with the evil djinn sealed in copper jars or bottles. One is imprisoned in a pillar with his head and arms sticking out. Another genie servant appears in the story of "Judar and his Brethren," where the main character gains a magic ring. Whenever he rubs the ring, the djinn who serves it will appear and obey any request. This story does bear a passing resemblance to Aladdin; the djinni Al-Ra’ad al-Kasif transports Judar home and helps him gain riches. Judar marries a princess and becomes Sultan, only for envious thieves to steal the magic ring and his wife. Unlike Aladdin, Judar is murdered by those who want the ring. In the end, the princess poisons Judar’s murderer and destroys the ring so that no one can ever possess it again. “Judar” does not appear in Galland’s translation. Dom Denis Chavis, a Syrian priest, published a Galland-inspired continuation of the Nights. One story, "The Tale of the Warlock and the Young Cook of Baghdad," bears a resemblance to the story of Aladdin, with a young man magically kidnapping a certain princess every night. To do this, the young man learns from a sorcerer how to summon the Jánn from beneath the earth. This is more of an involved black magic ritual involving needles, clay and meat. So there are traces of a legend where King Solomon imprisoned rebellious djinn inside bottles. They might be grateful enough to grant wishes when released, but they might also kill their rescuer out of sheer spite. Separately, in the story of Judar, is the theme of a ring which can summon an obedient djinn. There are several magical treasures in "Judar" – saddlebags which generate food, a sword which summons fire and lightning. The ring is just another object with mystical properties - a common theme across many mythologies. So, back to Aladdin. The magic ring is familiar. However, the magic lamp still raises some questions. Why is it a lamp? Why not another ring, or why not a jar, which most imprisoned genies seem to be stuck with? The Spirit in the Blue Light Aladdin has a neighbor in European fairy tales categorized as Aarne Thompson 562, "The Spirit in the Blue Light." This tale type gets its name from the Brothers Grimm's story, “The Blue Light.” In this tale, a witch sends a soldier down a well filled with treasure to retrieve a blue light which never goes out. Abandoned at the bottom of the well, he discovers that when he uses the blue light to light his pipe, a dwarf will appear and carry out any request. The soldier commands the dwarf to get him out of the well, and not much later, to bring the local princess to his home at night. The princess manages to leave a trail marking his house. When the king finds out, the soldier loses the blue light and is about to be executed, but regains it at the last second and ends up marrying the princess and becoming king. Aside from the ending, the plot is identical to Aladdin. Blue fire is the hottest part of a flame, and has otherworldly associations, like will o’ the wisps that may lead the way to treasure. It might also be connected to lightning. However, the Grimms focused not on the otherworldly blue light, but on the fact that the soldier used it to light a pipe. They compared it to a Hungarian tale titled “The Wonderful Tobacco-pipe,” and to the flute in one of their other stories, “The Gnome.” Near the very end of “The Gnome,” there is one Aladdin-esque scene: a huntsman is trapped in an underground chamber and finds a flute. When he plays it, a huge crowd of elves appear and grant his request to be freed. The Grimms theorized that all of these stories were based on a story of a magic flute. However, going through a few different versions, there is an equally strong theme of light or heat sources. This is not even close to an exhaustive examination, but some common spirit-summoning tools in Tale Type 562 are:

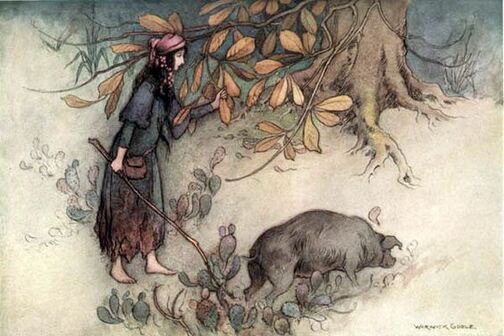

The Grimms also mention the legend of a thirteenth-century friar called Albertus Magnus. Rumors and legends about Albertus' magical studies abounded, one being a fifteenth-century poem, "Es war ein Kung in Frankereich.” There is no magical helper here, but part of the shape of Type 562 is clear. In his rebellious youth, Albertus magically carried a certain princess to his apartment every night. She was able to leave a trail of red paint to identify him. Albertus was set to be executed by the furious king, but escaped using a magical ball of yarn. How did the summoning of a spirit become tied to a light source? It reminds me a little of the idea of candles lit in prayer. But ultimately, searching for a reason for Aladdin's lamp in European fairytales is backwards, because Aladdin may be the ultimate source for the magical candle or light. Galland's version of the Arabian Nights was hugely popular, and obvious descendants of Aladdin appear in many European folktale collections. For instance, in 1853 Heinrich Pröhle collected a German folktale titled "Der Geist des Ringes und der Geist des Lichtes" which is a straightforward retelling of Aladdin with every single plot beat. There does seem to be a division between wholesale Aladdin retellings and variants of "The Blue Light." In “The Blue Light,” the protagonist uses his magical servant to kidnap the princess nightly, until she marks his house and her enraged father has the protagonist imprisoned. The protagonist loses his magical servant, regains it at the last second, defeats the king’s forces, and marries the princess. Aladdin does steal the princess away at night on a few occasions, but otherwise goes through the proper channels to marry her. The problem arises from his old enemy, the sorcerer. Aladdin does briefly face execution from his father-in-law when the sorcerer causes trouble, but the focus is on his battle against the old enemy who’s turned his tricks against him. The story of the young man kidnapping the princess via magic can be tracked at least the fifteenth century with the legend of Albertus Magnus. But the idea of the magic light summoning an obedient spirit can be tracked back to . . . uh . . . Aladdin, told by Hanna Diyab in 1709. The Life of Hanna Diyab Diyab's autobiography was rediscovered in the Vatican Library in 1993. Since then, some scholars have suggested that his stories were inspired by his own life. Hanna Diyab was a nineteen-year-old Maronite Christian from Aleppo with a longing to travel, when he encountered Paul Lucas, a French traveler (plus tomb raider and con artist). Lucas offered to hire Diyab as a manservant and take him to meet the king of France. Along the way, it was Lucas who would introduce him to Antoine Galland. Modern scholars have drawn connections between Diyab's autobiography and the story of Aladdin. Paulo Horta compares Diyab’s account of Louis XIV’s court to Aladdin’s processions, princesses and palaces. Diyab met Galland a few months after being introduced to court. Horta also mentioned that Diyab compared the bell of Notre Dame to an "egg made out of iron," located atop a "minaret," which rang so loudly that it scared the citizens. I wasn't able to check this against the source, but this would be an intriguing parallel to the deadly roc's egg that Aladdin's princess wants to hang in the dome of the palace. Not only can you see Diyab as Aladdin and Lucas as the magician, but one of Lucas' main goals was to bring home treasures and artifacts. Early in their travels, they found an underground tomb that Lucas wanted to investigate. He [Lucas] walked around the tomb, looking for a way in. He only saw a small opening, and asked one of the armed escort to go down through it. None of them did; they said that it could contain a wild animal, like a hyena, leopard, or something. … As we were talking, a shepherd walked by, and the officers asked him to go down. … The tomb was six feet and one span of the hand deep. The Frenchman said to the shepherd: ‘Go around the tomb and give me everything you find.’ He started to walk around and saw a human skull, which he handed over. It was the size of a large watermelon. The Frenchman told us it was the skull of a man. Then, the shepherd handed him another skull, which was smaller. The Frenchman said it belonged to a woman. He claimed that the tomb was that of rulers of the area. He threw the shepherd a piece of cloth and said: ‘gather everything you find on the ground and give it to me.’ The shepherd proceeded to do so, and among the things he collected we saw a large flat ring. The Frenchman examined it and said that it was rusty, and that there was no clear writing on it. He was not able to identify the metal from which it was made, nor whether it was gold, silver, or something else. He kept it with him. Then he said to the shepherd: ‘Feel around the walls of the tomb.’ As the shepherd did so, he felt a niche inside of which there was a lamp, similar to those of butter vendors, but he could not identify the material…. So someone is sent underground to retrieve treasures, and returns with a lamp and a ring. Was this an incident that influenced Diyab when he told the story of Aladdin? Or was his storytelling style affecting the way he wrote down his life story decades later? Hanna Diyab’s memoir is likely at least partially fictionalized. He had probably retold his journey many times over the years, embroidering or exaggerating. Paulo Horta points out a story of a private meeting with a French princess that probably would not have been allowed. Lucas described the tomb incident in his own memoirs, but only mentioned the skulls. (Diyab and Lucas’s travelogues cover some of the same events but portray them differently – for instance, they both describe being raided by pirates, but Lucas is an innocent victim in his version and a conniving sleazeball in Diyab’s.) In-story, I think the lamp and ring would be most equivalent to the magical ring in the story of Judar. It's simply a property of the magical objects that they summon otherworldly servants. Out-of-story, we know that Aladdin is the result of a collaboration between Hanna Diyab and Antoine Galland, and I agree that most of the story came from Diyab. What inspired him to make the magical object a lamp? I do like the idea that he was influenced by an incident on his journey, where a lamp was found in a buried tomb. Or the tomb incident could be irrelevant, just Diyab retelling his own life in the style of a fairytale. Maybe there is something in the idea of candles lit in prayer. Either way, I think Diyab's magic lamp is comparable to Perrault's glass slipper - a stroke of storytelling genius that forever defined the popular image of the fairytale. Sources

Other Blog Posts

1 Comment

The opening of the Italian fairytale "Prezzemolina" is near-identical to Rapunzel, but then the story takes a totally different direction. It becomes something like a gender-flipped versions of stories like "Master Maid" or "Petrosinella," where the hero is in danger from a villain, but is rescued by the villain's beautiful and magical daughter. In this version, it's a heroine who's rescued by the wicked witch's handsome son. There are two primary versions of the tale, so I'll list them in the order of publication.

Imbriani's Prezzemolina The story of "La Prezzemolina" begins just like Rapunzel and the older Italian "Petrosinella," with a pregnant woman craving parsley. Some fairies live next door, so she climbs into their walled garden to steal their parsley. They eventually catch her, and tell her that they will one day take away her child. The woman has her baby, who is named Prezzemolina (Little Parsley). The fairies collect her when she reaches school-age, and she grows up as their servant. They give her impossible tasks and threaten to eat her if she fails. Fortunately Memé, the fairies' cousin, arrives and offers to help in exchange for a kiss. She sharply refuses the kiss, but he helps anyway with a magic wand and mysterious powers. She goes through several tasks, including going to Fata Morgana (Morgan le Fay) to collect the "Handsome Minstrel's" or "Handsome Clown's" box, only to open the box and lose the contents. But Memé is always there to assist, and in the end they destroy all of the fairies and get married. The tale appeared in Vittorio Imbriani's La Novellaja fiorentina (1871, p. 121). Italo Calvino, who adapted it in his Italian Folktales (1956), called it "one of the best-known folktales, found throughout Italy." He noted the presence of "that cheerful figure of Memé, cousin of the fairies." This could imply that Memé is a popular folk figure. Imbriani, the original collector, suggested that Memé is Demogorgon, the terrifying lord of the fairies in the 15th-century poem Orlando Innamorato. The name Demogorgon probably came from a misreading of the word “demiurge” in a 4th-century text, and developed to mean either an ancient supreme god or a demon. The biggest similarity I can see is that Fata Morgana plays a villainous role in both “Prezzemolina” and Orlando Innamorato. I’m not sure of Imbriani’s thought process, other than the fact that Orlando vividly describes Demogorgon punishing the fairies. Imbriani also compared Memé to the fairy cat Mammone, who hands out magical rewards and punishments in the fairytale “La Bella Caterina.” Again, I’m not clear on why, except that Memé sounds kind of like Mammone. I may be missing Italian context. In both cases, Imbriani implies that Memé holds some kind of power or authority over the fairies. This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me; Memé seems to be on the same level as the fairies, and is apparently the black sheep of the family. The fairies seem automatically suspicious that he might help a human girl. When they see Prezzemolina’s first impossible task completed, they immediately guess (as Calvino puts it), “our cousin Memé came by, didn't he?" They later tell Meme their plans to kill Prezzemolina, perhaps in an attempt to goad him. Visentini's Prezzemolina Another version, also titled "Prezzemolina," appeared in Canti e racconti del popolo italiano by Isaia Visentini (1879). This version begins with seven-year-old Prezzemolina eating parsley from a garden on her way to school and being kidnapped by the angry witch gardener. Here, the handsome rescuer who only wants a kiss is Bensiabel, the witch's son. This version features different tasks, but one quest still involves retrieving a casket, and in the end Bensiabel kills the witch and Prezzemolina finally agrees to marry him. Andrew Lang published a translation in The Grey Fairy Book (1900), but changed the plant and the name. The vegetable garden became an orchard, the parsley became a plum, and the heroine's name became Prunella. This resembles early translations of Rapunzel where English writers struggled to render the name and came up with "Violet" or "Letitia." However, in this case the reason may be that Lang had already published The Green Fairy Book (1892) with the German tale "Puddocky," which had a near-identical opening with a heroine named Parsley. Lang did not mention a source, but "Prunella" is clearly drawn from Visentini's story. Bensiabel's name may come from the Italian "ben" (well) and "bel" (nice). This seems supported by the French translation, Belèbon, in Edouard Laboulaye's 1881 retelling "Fragolette." Belèbon may be from the French "bel" (attractive) and "bon" (good). Like Lang, Laboulaye turned the parsley into a fruit, in this case strawberries (Italian fragola). Cupid and Psyche As Calvino implies, there are a number of similar tales. Charlotte-Rose de la Force - the author who gave us the modern Rapunzel - also wrote a story in 1698 called "Fairer-than-a-Fairy" which followed some of the same motifs as Prezzemolina. The heroine, Fairer-than-a-fairy, is kidnapped by Nabote, Queen of the Fairies. Nabote's son Phratis falls for Fairer and helps her. Calvino published another tale with similar plot beats, titled "The Little Girl Sold with the Pears" (p. 35), noting that he made numerous edits. The original, "Margheritina," collected by Domenico Comparetti, is even closer to Prezzemolina, with the heroine's unnamed prince being the one to magically aid her. Aarne-Thompson-Uther Type 425, The Search for the Lost Husband, is a large family of tales with many subtypes. 425C is Beauty and the Beast. In the current breakdown, 425B is "The Son of the Witch." When Hans-Jorg Uther codified this, he wrote "The essential feature of this type is the quest for the casket, which entails the visit to the second witch’s house. Usually the supernatural bridegroom is the witch’s son, and he helps his wife perform the tasks." In the Pentamerone (1634-1636) is a story titled "Lo Turzo d'Oro" - literally "The Trunk of Gold," but also titled "The Golden Root" in translation. When the heroine Parmetella is completing her tasks to win back her husband Thunder-and-Lightning (Truone-e-llampe), he helps her through each task. This is the bloodiest variant I've read. Laura Gonzenbach's story "King Cardiddu" also features a male character who's imprisoned by the villain but manages to provide magical help to the heroine. Giuseppe Pitre collected a Sicilian tale called "Marvizia" (Fiabe, novelle e racconti popolari siciliani, 1875). The heroine is named for her resemblance to a "marva" or mallow plant. The villain is an ogress named Mamma-Draga. It's a long and elaborate tale, but in a section similar to Prezzemolina's quests, Marvizia is assisted in her tasks by a giant named Ali who works for Mamma-Draga. However, he's not the love interest; Marvizia marries a captured prince whom the villainess turned into a bird. (This story features an ogress who eats people "like biscotti," and the hero wishes for a literal bomb with which to blow up her castle. I just felt that was important to note.) "Cupid and Psyche," recorded in the second century, is the uber-example. Psyche loses her divine husband Cupid and must complete her goddess-mother-in-law Venus's tasks to get him back. Although the tasks are meant to be impossible, Psyche completes each one with help from nearby creatures. Finally she must go to the Underworld and retrieve a box from Persephone, but foolishly opening it, falls into a deep sleep. At this final point, Cupid steps in and rescues her. Prezzemolina and similar tales are neighbors of the "Cupid and Psyche" tale - related to stories like "East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon." They don't have the beastly transformation, or the scene where the love interest is about to be forced to marry the wrong girl. However, they share the motif of the girl faced with impossible tasks including retrieving a magical box, and being aided by her supernatural lover. Taken to its furthest conclusion, this casts interesting parallels from Prezzemolina to Beauty and the Beast tales. Beauty's father is forced to hand his daughter over because he stole a flower from the Beast's garden - a very Rapunzel moment. Prezzemolina's suitor constantly begs for a kiss, the Beast asks Beauty to marry him, and the Frog Prince requests to sleep on his princess's pillow. Memé and Bensiabel would then be related to Cupid and the family of beastly bridegrooms. Echoing Cupid, they're benevolent sorcerers or minor deities smitten with a mortal girl, who defy their divine or monstrous mothers to help. Unlike the lost husband figure, the Memé figure is never under a curse, and is right there alongside the heroine for the whole tale. She has no need to pursue him, because he's wooing her the entire time. With its unique mix of fairytale tropes, I'm not sure whether the Prezzemolina type would be best categorized as 425B, "The Son of the Witch," as 310, "The Maiden in the Tower," or as something else entirely. Other Blog Posts |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed