|

So far, in examining the history of Rapunzel, we have seen two very different endings to the Maiden in the Tower tale.

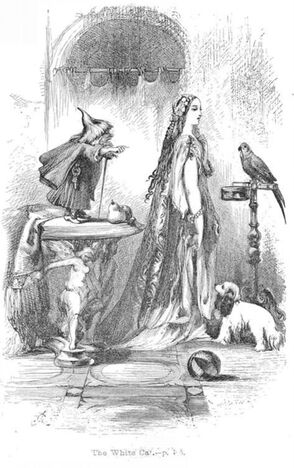

In the literary La Force/Grimm ending, Persinette/Rapunzel's hair is cut, the prince falls from the tower and goes blind, and they reunite later in the wilderness where her tears cure his blindness. But in the older and more widespread ending, derived from oral tradition, the boy and girl flee from an ogre's chase in a "magical flight" where they use enchanted tools to evade the monster. Rapunzel is Aarne–Thompson Type 310, "The Maiden in the Tower." The oldest known Rapunzel, "Petrosinella," fits this, but is also close to Type 313, "The Girl Helps the Hero Flee." Type 313 tends to feature tough, clever heroines who use magic to get their boyfriends out of trouble and run circles around the villain. Italian Rapunzels - or more properly, Parsleys - are clever and magically powerful. Italian Rapunzels Although Basile's version is a literary tale, there are many examples of the tale in collected Italian folklore. "Snow-White-Fire-Red," recorded in 1885, overlaps with AT 408, "The Three Oranges," with its strikingly colored heroine, the prince on a hopeless search for her, and their separation when he forgets her. It lacks the significant Rapunzel "garden scene" of stolen vegetables. However, it still has the the tower, the ogress, the hair-ladder, and the heroine's use of magic to escape with her prince. In the end, the ogress curses the prince with amnesia, and Snow-White-Fire-Red has to get him to remember her. There is a Greek version titled "Anthousa, Xanthousa, Chrisomalousa" (Anthousa the Fair with Golden Hair). Some stories feature the "garden scene" beginning of Rapunzel, but are actually different tale types. Italo Calvino, in his Italian Folktales (1956), includes "Prezzemolina" (meaning, again, Little Parsley). There is no hair or tower, but instead a parsley-loving girl forced to serve a witch until her magician boyfriend rescues her. Variants on this are Prunella (Plum) and Fragolette (Strawberry). "The Old Woman of the Garden" has the same opening, but there is no prince at all. Instead, the girl shoves the witch into her own oven and goes home to her mother. French Rapunzels In Italian versions, the ogress is dangerous and powerful, but the girl is powerful too. By contrast, French versions make the heroine and hero totally defenseless before the fairy's or ogress's might. La Force may have created an original ending to the tale, but the touch of tragedy ties in with oral French equivalents. The heroes are passive, with Persinette's only ability being her healing tears; the fairy wields all the power, and they get their happy ending when she feels sorry for them. "Persinette" is actually an exception from some French relatives in that it ends so happily! Revue des traditions populaires, vol. 6 (1891) featured a French version called Parsillette (you guessed it - Little Parsley). This tale has so many similarities to Persinette that it may have been influenced by it, except for the addition of a talking parrot who betrays Parsillette's secret. Except that in the end, Parsillette is struck with ugliness by her godmother's curse. She hurries back to beg her godmother's forgiveness and plead for her beauty back, seemingly unconcerned that her boyfriend has dropped dead. It ends abruptly: "Later Parsillette married a very wealthy prince, and she never knew her parents." "The Godchild of the Fairy in the Tower" is another strange one, very short, and apparently influenced by literary versions of the story. A talking dog, rather than a parrot, betrays the secret. At the godmother's curse, the unnamed golden-haired girl becomes a frog, and the prince grows a pig's snout. The End. I'm not making this up. You could trace tragic endings as far back as the Greek myth of Hero and Leander, where the hero drowns trying to swim to his lover's tower prison, and she then commits suicide. Or there's the third-century legend of Saint Barbara, where the tower-dwelling heroine discovers Christianity (making Christ, in a way, her prince) and becomes a martyr at her father's hands. However, the odd little tale of "The Godchild" reminds me of another tale, where a Rapunzel-like character ends up in a tale similar to the Frog Prince. Puddocky This is a German tale, "Das Mährchen von der Padde" (Tale of the Toad), adapted by Andrew Lang as "Puddocky." A poor woman has a daughter who will only eat parsley, and who receives the name "Petersilie" as a result. In the German version, Petersilie's parsley is stolen from a nearby convent garden. The abbess there does nothing until three princes see the girl brushing her "long, wonderful hair," and get into a brawl over her right there in the street. At that point, the infuriated abbess wishes that Petersilie would become an ugly toad at the other end of the world. (Interestingly, Laura J. Getty points out several traditional versions of the Maiden in the Tower where the girl's caretaker figure is a nun.) In Lang's version, instead of an abbess there's a witch who takes Parsley into her home. Lang also specifies that Parsley's hair is black. From there, in both versions the enchanted toad breaks her curse by aiding the youngest prince in his quest for some enchanted objects. She becomes human again and they marry. It's an example of the Animal Bride tale, albeit with a beginning reminiscent of Rapunzel - a similarity which Lang enhanced by turning the abbess neighbor into a witch foster mother. "Blond Beauty" is a very short French version which, like Parsillette, has a parrot reveal the girl's affair. There's also a much longer and more elaborate literary version from France: The White Cat A tragic Rapunzel tale is embedded in Madame D'Aulnoy's literary tale of the White Cat, another Animal Bride tale, published in 1697 - the same year as "Persinette," by an author from the same circle. Late in the story, after the magical quest and curse-breaking parts are over, the heroine explains how she came to be cursed. Her mother ate fruit from the garden of the fairies, and agreed to let the fairies raise her daughter in exchange. The fairies built an elaborate tower for the heroine, which could only be accessed by their flying dragon. For company, the heroine had a talking dog and parrot. One day, however, a young king passed by, and she fell in love with him. She convinced one of the fairies to bring her twine and secretly constructed a rope ladder. When the king climbed up to her, the fairies caught him in her room. Their dragon devoured the king, and the fairies transformed the princess into a white cat. She could only be freed by a man who looked exactly like her dead lover. Rapunzel as a "Beauty and the Beast" Tale "Puddocky" and "The White Cat" focus more on the animal transformation than on the "Maiden in the Tower" elements. They keep Rapunzel's "garden scene," but the main plot is of a prince encountering a cursed maiden in a gender-flipped Beauty and the Beast tale. Not all "Animal Bride" tales (AT type 402) have this overlap with Rapunzel, but quite a few Rapunzel tales feature the maiden losing her beauty in some way. Laura G. Getty mentions other versions which start out like Petrosinella, with the flight from the ogress, but which then feature an additional ending where the ogress curses the girl to have an animal's face. They have to convince the ogress to take back the curse before a marriage can take place. An Italian example is "The Fair Angiola," cursed to have the face of a dog. The Complete Rapunzel Put everything together from all the versions, and a much more elaborate version of Rapunzel emerges:

Take out a few scenes here or there, and you can get all sorts of combinations. Delete the animal transformation and separation and you've got the Italian Petrosinella. Focus on the transformation and leave out the magical flight, and you have the German Puddocky. Remove the happy ending and you have "The Godchild of the Fairy in the Tower." Keep it all together and you have, more or less, "Fair Angiola." Even with La Force's unique creative twists, I was surprised to see how much Persinette matched up with other tales. The temporary loss of her prince and exile in the wilderness is a common trial. The fairy cutting Persinette's glorious hair is parallel to the traumatic transformation in other stories. In versions like “Parsillette" or “The Fairy-Queen Godmother,” the fairy is the source of the heroine’s wondrous beauty and removes it when the heroine runs away. Persinette’s godmother also bestows beauty (including presumably her unique hair) at her baptism. When she cuts off Persinette's hair, she is removing her goddaughter's special privileges and gifts. This is accompanied by a change in location: instead of a bejewelled silver tower, Persinette now lives in an even more isolated house. This dynamic is quite different from laying a curse of animal transformation. However, the implications are lost in the Grimms' retelling. I find it interesting that there are many versions where the girl isn't just transformed, but where she needs to heal (or perhaps resurrect?) the prince. Persinette cures her prince's blindness. Snow-White-Fire-Red and Anthousa fix their princes' amnesia. The White Cat and Parsillette replace their dead princes with suspiciously similar doppelgangers. If "The Godchild of the Fairy in the Tower" continued, one presumes that the heroine would need to not only break her own curse but cure her prince of his pig snout. In all this, the witch-mother is a mysterious and morally grey character. Angiola's witch is a generous guardian who releases her from her curse, but is also a predatory figure (biting a piece from Angiola's finger at one point). The White Cat's fairy guardians are more malicious, pampering her but also being demanding and violent. Often the witch is merely a force to be evaded or killed. But also fairly frequently - as seen in Angiola, Blond Beauty, The Fairy-Queen Godmother, and Persinette - she does fully reconcile with the heroine and release her from her curse. In "Anthousa, Xanthousa, Chrisomalousa," rather than cursing the prince, the ogress warns Anthousa that he'll forget her and gives her the instructions to win him back. Conclusion Rapunzel is, at its core, a tale of an overprotective parent hiding away a maturing daughter so that she won’t encounter men. Some versions make her female guardian a nun - reminiscent of young noblewomen being sent to a convent to guard their virginity until they were of age to marry. Elements of desire and lust show through in the early garden scene, with the suggestive elements of the pregnant woman’s unstoppable cravings for parsley (an herb accompanied by erotic symbolism). In the story of Puddocky, the girl herself is the one obsessed with the food. The idea of forbidden fruit in a garden leading to sin is as old as the story of Adam and Eve. This beginning sets up the path of sexual temptation which Parsley is locked away to avoid, but her very name hearkens back to it. Although the heroine typically ends up married despite her parent-guardian’s best efforts, she must endure trials before finally marrying her lover. These trials are directly related to her disapproving guardians, who did not bless the marriage. The emphasis on family approval is evident even in the early tale of Rudaba. In the case of Parsillette, she leaves her boyfriend, begs her godmother to take her back, and submits to an arranged marriage, restoring her to societal status quo. Less exciting, but possibly more realistic. And in "The Godchild," both lovers are simply out of luck. La Force gave Persinette the happy ending found in Mediterranean versions, and a reconciliation with the parental figure more common in French versions. But she did so while explicitly showing that the fairy was trying to protect Persinette from a bad fate, apparently out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Other writers nodded to Parsley’s activities with the prince – Basile had the prince visit Petrosinella at night to eat "that sweet parsley sauce of love," a line that gets removed in a lot of versions. But La Force, uniquely, had that relationship lead to the natural result: pregnancy. The Rapunzel tale type could be a romantic story of a girl escaping her strict family and running away with the boy she loves. However, the additional ending served as an extra cautionary fable for young noblewomen of the time, in a patriarchal society where they had little power. The story doesn't end with running away together and enjoying the "parsley sauce of love." The heroine has squandered the wealth and gifts of her family. She's no longer a virgin. Maybe she's even pregnant. What if she loses her beauty? What else can she offer as a bride? The boy is the one with power in the relationship; what if he forgets her and plans to marry someone else? She may have to fight for him. She may end up alone in poverty. But quite a few stories serve as reminders that her family may still be open to reaccepting her. Even with the eventual happy ending, in the era the stories were told, a young noblewoman who made the same choices as Parsley would undergo significant hardships. Stories

Analyses

And more: Text copyright © Writing in Margins, All Rights Reserved

1 Comment

David L

10/26/2022 10:08:44 pm

A great collection of similar tales. I liked seeing all of the different variations across Europe. There was a lot of humor in here too, like the pig snout ending. The bullet list of events was so intriguing, that all the different stories you cited had so much in common. I also learned a lot from the historical perspective you provided. The context of life for a noblewoman

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed