|

There was once a king and queen that lived very happily together, and they had twelve sons and not a single daughter. We are always wishing for what we haven't, and don't care for what we have, and so it was with the queen. One day in winter, when the bawn was covered with snow, she was looking out of the parlor window, and saw there a calf that was just killed by the butcher, and a raven standing near it.

"Oh," says she, "if I had only a daughter with her skin as white as that snow, her cheeks as red as that blood, and her hair as black as that raven, I'd give away every one of my twelve sons for her." The moment she said the word, she got a great fright, and a shiver went through her, and in an instant after, a severe-looking old woman stood before her. "That was a wicked wish you made," said she, "and to punish you it will be granted. You will have such a daughter as you desire, but the very day of her birth you will lose your other children." This is from the Irish story of "The Twelve Wild Geese," a variant of Aarne-Thompson type 451, the Brothers Turned into Birds. Interestingly, it begins with nearly the same incident as "Snow White and the Seven Dwarves." In many stories of Type 451, the birth of a daughter somehow coincides with the loss of her older brothers. When she grows older, she takes on the responsibility of seeking them out and saving them. She travels into the wilderness until she finds her brothers' new home. Sometimes she hides or secretly does housework for them until they discover her. For various reasons, the brothers are cursed (usually turned into birds). She can only free them by remaining silent for years while she makes shirts for them. At this point, a king finds her alone in the forest. He marries her, but his mother takes a dislike to her and tries to convince him that the girl is a witch. The mother goes so far as to kidnap the heroine's newborn children, cast them out to die, and then accuse the heroine of killing and eating them. The heroine, still sworn to silence, can do nothing to defend herself even when she's about to be burnt at the stake. However, she manages to finish her task in the nick of time, restores her brothers to human form, and everything turns out fine. She gets her kids back, the king learns the truth, and the mother-in-law is punished. It's possible that some Type 451 stories were influenced by elements of Snow White. In "The Twelve Wild Ducks" (from Norway) and "The Twelve Wild Geese" (from Ireland), a queen wishes for a child who is white, red and black, and this child is subsequently named Snow-White-and-Rose-Red. In "The Six Swans," it is a hateful stepmother who curses the brothers. On the other hand, quite a few versions of Snow White begin exactly like Type 451, with the brothers going missing. Instead of moving in with dwarfs, the Snow White character winds up with her long-lost brothers. Some examples of this are "Udea and her Seven Brothers" from Libya, "The Girl of the Woodlands, Her Brothers and the Rakshasa" from India, a tale from Asia Minor collected by R. M. Dawkins, and Shakespeare's "Cymbeline." If you bring "Sleeping Beauty" into the mix, there are even more similarities. The Italian "Sun, Moon and Talia" and Perrault's "Sleeping Beauty" don't end when the heroine awakens from her sleep. In "Sun, Moon and Talia," a king rapes the sleeping Talia and begets twins upon her, which eventually wakes her. However, he already has a wife, who in a jealous rage tries to have Talia and her children cooked and eaten. Fortunately, she fails. In Perrault, the first wife is adapted into the king's mother instead. This episode seems unfamiliar until you realize it's really a version of "Snow White," with the sequence of events switched around. Similarly, in the Indian "Princess Aubergine" (yes, Aubergine), when a king takes an interest in the heroine, his first wife becomes jealous. There are no seven dwarfs, but the first wife has seven sons whose deaths stall her and thus protect Aubergine. Eventually, the wife's plots succeed and Aubergine is left in a deathlike coma. Here, again, the king impregnates the heroine while she's unconscious. In these three tale types - Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, and "The Brothers Turned into Birds" - the sequence of events are a little different, but they are generally the same events. First, there's the main character's birth. Snow White stories often begin with a childless woman's wish for a child. "The Brothers Turned into Birds" has a woman with many sons wishing for a daughter instead. In the Grimms' "Briar Rose," the heroine is born after her parents long for a child. The colors white, red and black are a long-standing theme across literature, but tend to recur in Snow White tales. In all three of the tale types discussed here, it's common to find mentions of roses. The heroines have names like Snow-White-and-Rosy-Red, Briar Rose, Blanca Rosa or Rose-Neige. Red and white flowers, particularly roses, are associated with the heroine of Hans Christian Andersen's "The Wild Swans." When turned into ravens or swans, the enchanted brothers tie into a black or white color scheme. In both "Snow White" and "The Brothers Turned into Birds," the heroine goes out into the wilderness and discovers a house inhabited by a group of men, whether they be dwarves, robbers, or her long-lost brothers. She does domestic work for them, and they protect her from outside threats, at least for a while. Then there's the jealous rival who attempts to send her to her death. All three tales focus on a maternal figure devouring her children. Snow White's stepmother wants to eat her lungs and liver. Sleeping Beauty's mother-in-law tries to cook her and her children as a meal. In both cases, the executioner (a huntsman in Snow White, a chef in Sleeping Beauty) takes pity on the heroine and substitutes an animal to be eaten in her place. Meanwhile, in "The Twelve Wild Ducks," the mother-in-law accuses the heroine of cannibalizing her own children. To enforce the lie, she throws the heroine's children to wild animals, but the animals spare them. The same basic ideas are there, just a little scrambled. While Sleeping Beauty and Snow White narrowly escape being cooked, the heroine of "The Brothers Turned into Birds" faces burning at the stake. Similarly, Snow White's stepmother gets the punishment of dancing in red-hot iron shoes until she dies. In all three cases, there's a curse involved. Sometimes there's also textile work. Talia and other Sleeping Beauties fall into a coma when they pierce their fingers spinning thread. The heroine of "The Brothers Turned into Birds" often has to break her brothers' curse by making shirts for them - a process which involves picking, carding, spinning and knitting. The biggest difference is that unlike Snow White and Sleeping Beauty, the heroine of "The Brothers Turned into Birds" never undergoes an enchanted sleep. Instead she spends a period of self-imposed silence while she labors to break her brothers' curse. However, the long isolation in the wilderness until her discovery by a king is still the same. The king finds her deep in the forest - whether in a castle surrounded by thorns, in a glass casket, or sitting in a tree. Stricken by her beauty, he immediately claims her. Uncomfortably for modern readers, the heroine is unable to communicate, since at this point she is either unconscious or sworn to silence. She gives birth while still in this state. As said before, many stories share motifs. However, these three stories dovetail in fascinating ways. BIBLIOGRAPHY

0 Comments

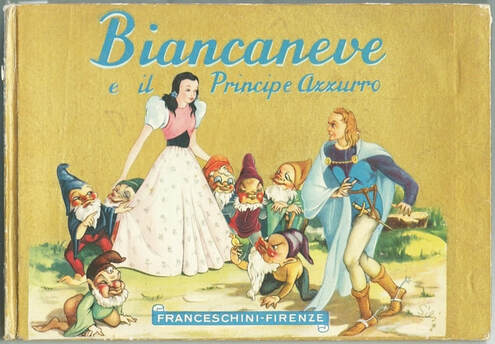

Have you ever wondered how you say "Prince Charming" in other languages? In several Romance languages, the term translates to "The Blue Prince" and is a common term for the perfect man. There's the "príncipe azul" (Spanish), "príncep blau" (Catalan), "principe azzurro" (Italian), and "prince bleu" (French). In all cases, the idea translates to what an English-speaker would call a Prince Charming or a knight in shining armor. Variants of this term go back at least to the 18th century.

Zadig ou la Destinée by Voltaire (1747) features a joust in which the hero Zadig wears white armor and defeats a man in blue armor, who is referred to briefly as "le prince bleu." This is only a passing line, but one wonders if it was a reference to a well-known phrase. Sur la scène et dans la salle. Miroir des théâtres de Paris (1854) describes a play featuring the role of "prince Azur" (p. 46). The Revue de France in 1879 mentions "le prince bleu des contes de fées." Victor Hugo's Les quatre vents de l'esprit (1881) has "le prince Azur" (p. 252). "Le prince Bleu" and "roi Charmant" (King Charming) both get a mention in Jules Claretie's Noris: mœurs du jour (1883, p. 37). In Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne by Francois-Marie Luzel (1887), a character in the tale of "Le Prix des Belles Pommes" is called Le Prince-Bleu. He is the hero's strongest rival for the princess's hand, but receives a dismal fate while the despised hero triumphs. By 1893, La Union literaria defines "Príncipe Azul" as a character "de una mitologia fastidiosa ser inverosimil y aereo" (of an annoying mythology, improbable and airy). This isn't even close to an exhaustive list. Oddly enough, in quite a few of these examples, the blue prince gets set up as the classic knight in shining armor, but is either disparaged as a foolish idea by the narrator or given a comeuppance by the story. So why "blue"? Apparently there has been some speculation that King Vittorio Emanuele III of Italy was the original for the Blue Prince. Blue was the traditional color of his family, the House of Savoy. An article by Paolo Zollo was titled "Che il Principe Azzurro sia stato Vittorio Emanuele?" (Was the Blue Prince Vittorio Emanuele?) in Messaggero veneto (1982). A connection had been drawn previously by Giovanni Artieri, who described Vittorio's wife Elena as "Cenerentola" (Cinderella) and Vittorio as "un Principe Azzurro, azzurro Savoja" - "a Blue Prince, Savoyan blue." (Il tempo della Regina, 1950, p.52). Unfortunately for this theory, Vittorio and his wedding (which seems to have inspired the comparison) are a bit late. One possibility is that "the blue prince" comes from the idea of blue-blooded royals. Blue-blooded has long been a way to refer to the nobility. The nickname is derived from the Spanish "sangre azul" dating at least to 1778. It was theoretically inspired by the nobility, with their fair skin that showed off blue veins. Or the prince might literally be wearing blue. Blue pigment was expensive in the past and often marked the clothing of the nobility. The Oxford English Dictionary lists a number of uses of the term "royal blue," including an advertisement in the 1782 Morning Herald & Daily Advertiser: "Among other colours are the royal blue, the green, pink, the Emperor's eye, straw, &c." Similarly, there is a 1787 reference to a sky "of the deepest royal blue." There are a multitude of possible explanations for the "blue prince" term. According to this forum thread, one Hungarian term for a Prince Charming is "kék szemű herceg," or the blue-eyed prince. So depending on how you look at it, the term could be a reference to blue blood, blue clothing, blue eyes, or something else entirely. Whichever the case, those three things all accentuate the relevant traits of the archetypal fairytale prince. He's royal, rich, and good-looking. All the same, it seems writers had tired of this ideal even in the 19th century, disparaging the character as unrealistic or showing a less promising hero who defeats him. |

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed