|

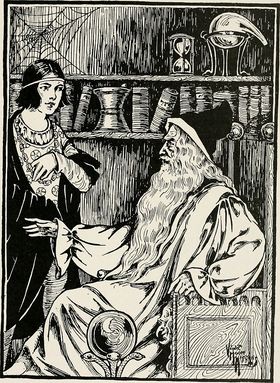

The Scottish tale of Childe Rowland was first published by Robert Jamieson in 1814. This tale follows the children of King Arthur - specifically, a son called Child Roland and a daughter called Burd Ellen. (Child and Burd are noble titles for a knight and lady.) The King of Elfland steals Burd Ellen, and one by one her brothers seek her. The two oldest never return from Elfland. Roland, the youngest, goes to Merlin for advice, then fights his way into the otherworld with his trusty claymore. There he finds his sister, who offers him food, but he remembers Merlin's wisdom and refuses to eat. The elf king arrives, chanting, "With a fi, fi, fo, and fum! I smell the blood of a Christian man!" Roland fights him to a standstill and forces him to resurrect his two brothers, killed trying to save Ellen. The elf king anoints them with red liquid from a crystal phial and brings them back to life. With that, the four siblings proceed home.

Jamieson heard the story from a tailor at age seven or eight, and reconstructed it years later. He mentions that he left out some details because he wasn't sure of his memory. He added in the names of Arthur, Guinevere, Excalibur, and the location of Carlisle, based on the fact that Merlin appeared in the story. Although the story as Jamieson tells it can only be dated to the early 1800s, there is evidence of the story being older. For one thing, Rowland's name appears in Shakespeare's King Lear (1606). The line is spoken by Edgar, posing as a mad fool who rambles only nonsense. Child Rowland to the dark tower came, His word was still,--Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man. This is echoed in Jamieson's version with the "fi, fi, fo, fum" chant; Jamieson said that it was one of his most enduring memories from hearing the tale for the first time. Later, the folktale collector Joseph Jacobs published a retelling which called the King of Elfland's dwelling the "Dark Tower," drawing on the King Lear verse. Previously, other readers believed that the nonsense verse might be a mix of references - for instance, "Childe Roland" might be from the eleventh-century French poem Song of Roland, and the "fie, foh and fum" from "Jack the Giant-killer." Jamieson presented an alternative: the Scottish story of Childe Roland. This all began in his 1806 collection Popular Ballads and Songs. In the first volume, he described three Danish ballads about a character named Child Roland. He gave the first of these ballads in the second volume of Popular Ballads, and the second two in Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, along with his retelling of the English version. From the very beginning, Jamieson was focused on that one line in Shakespeare - more on that later. The Danish ballads came from the 1695 work Kaempe Viser or Kæmpevise. It's not clear whether any of them appeared in the original, shorter edition of 1591, and I have not been able to locate a copy of either, so I have to base my knowledge on Jamieson's translation. In the first, the main characters are an unnamed youth and Svané, the children of Lady Hillers of Denmark. The second has Child Roland and Proud Eline (no parentage given), and the third has Child Aller and Proud Eline (children of the king of Iceland). The second version is the longest and most dramatic, and uses nearly the same names as Jamieson's Scottish tale. In all three ballads, the villain is a monstrous giant or merman known as Rosmer Hafmand, who dwells in a castle beneath the sea. Roland (or Aller) sets sail in search of his sister and reaches Rosmer's castle after his ship sinks. He enters the castle as a spy and lives there for some time. In the second version, Roland and Eline begin an incestuous relationship and Eline becomes pregnant. In these ballads, there is no daring battle between Roland and his sister's abductor; instead, he pretends he's leaving, packs his sister in a chest, and asks Rosmer to carry it for him. He rescues the captured maiden through trickery instead of combat. Jamieson and others argued that Childe Rowland was an ancient English tale which spread to Denmark. This was Jamieson's pet theory which he was pushing very hard. Besides King Lear, there are a couple of older works with plots similar to "Childe Rowland." In The Old Wives' Tale, a 1595 play by George Peele, there are multiple plot threads and fairytale references. The most relevant plot thread deals with two princes searching for their sister, stolen away to the sorcerer Sacrapant's castle. (All of the names are from the Orlando Furioso). They are aided by an old man (similar to Merlin) but eventually all three siblings are rescued by another party. Similarly, in the masque Comus, first presented in 1634, the necromancer Comus steals away an unnamed lady to his palace, where he tries to entice her to eat the food he offers. She holds out until her brothers arrive to rescue her. Even then, the lady can only be freed by touching her lips and fingers with a magic liquid, similar to the ointment which resurrects Roland's brothers. The similarities are clear and have been pointed out by various writers. So we know that:

Some writers have tried to strengthen the tale's ties to King Arthur, but I think this is a mistake. Roger Sherman Loomis, in Celtic Myth and Arthurian Romance, suggests that Child Rowland "seems to go back through an English ballad to an Arthurian romance" and is ultimately derived from the 8th- or 9th-century Irish tale of Blathnat. Blathnat, the lover of Cuchulainn, is abducted by a giant named Curoi. At least two Arthurian romances include this sequence of events: De Ortu Waluuanii (The Rise of Gawain), with the villain as the dwarf king Milocrates, and The Vulgate Lancelot with the villain being the giant Carado. Although the characters vary, the story remains the same: a maiden is abducted by a being who can only be slain by one weapon. Her lover sneaks into the being's fortress to rescue her. The damsel steals the weapon and gives it to her lover, who beheads the villain. This is the family of tales to which Loomis tried to tie Childe Rowland. However, the only thing they really share is the motif of the abducted maiden's rescue. That motif is incredibly widespread through many different tale types. I would say Childe Rowland bears more resemblance to "Sir Orfeo" (a middle English retelling of the myth of Orpheus) than it does to Blathnat's story. In addition, Loomis' theory ignores that "Childe Rowland" is a reconstruction and that Arthur and Guinevere were added in based on a single mention of Merlin. BIBLIOGRAPHY

2 Comments

Hans Christian Andersen's tale of "The Marsh King's Daughter" (1858) follows Helga, the daughter of a monster and a kidnapped princess. During the day she is beautiful like her mother but violent and cruel; during the night, she is hideous like her father but sad and gentle. There are heavy Christian themes, with Helga meeting a noble missionary priest and breaking free of her curse through the power of God. At the end, Helga and her mother return to Egypt. Helga is about to be married to a prince, but seems distracted from her impending wedding. She has spent a lot of time meditating on Christianity and the now-dead priest who saved her. She prays for a glimpse of Heaven and is allowed to see its glory for three minutes. When she returns, however, she learns that "many hundred years" have passed since she vanished on her wedding day. Upon hearing this, her body crumbles to dust, freeing her to return to Heaven.

This story always pulled me in at the beginning with its concept and descriptions, but the ending was just depressing. Yes, Helga’s greatest desire is to go to heaven, but I still found the ending dissatisfying and discomfiting. There's just something freaky about your heroine going all Infinity War at the end. And I say this as someone who grew up loving stories of martyrs and saints. Andersen, as usual, pulled in a lot of fairy tale concepts. The beginning is very familiar, with a group of swan maidens taking off their feathery cloaks to bathe, and a man who captures and forcibly marries one of them. However, this trope usually features a human man winning a supernatural bride. In this case, the swan maidens are human princesses and the man is a literal swamp monster. And the ending of Helga's story is a popular medieval legend. In fact, that legend is a fairy motif repackaged by Christian storytellers. This motif has been incredibly widespread from ancient times up to modern literary tales like Rip Van Winkle. Urashima Tarō, a Japanese tale dating back to the 8th century, centers around a fisherman named Urashima who catches a turtle which turns out to be a princess of the sea. She takes him away to her blissful underwater kingdom, where he has eternal life and everything he could ever want. What he wants, though, is to visit his old home on land. He arrives only to find that centuries have passed and everything he knew is gone. The ending varies, but generally all of his years come upon him at once and he is left an old man, his immortality gone. And in The Voyage of Bran from Ireland, also from around the 8th century, much the same thing happens. After seeing a beautiful silver branch, Bran sets out for the Land of Women, the utopian island where the branch grew. He and his men live there for what seems like a year, feasting and totally happy, but one of them feels homesick. The band returns to Ireland briefly, and learns that centuries have passed and they are remembered only as legends. The homesick man steps onto dry land and turns to dust, and his companions decide they'd better book it back to the Land of Women. King Herla, an English character from the 12th century, had the same experience after dealing with a dwarf king. And in a 12th- or 13th-century lai, the knight Guingamor (just like Urashima and Bran) immediately regrets leaving his supernatural sweetheart. The moral in Urashima and Bran's tales is to not break taboos. In both cases, a man ignores the commands of his lover (who is basically a goddess) and dooms himself to a terrible punishment. King Herla's post-Christian story has the moral that the supernatural creatures of older religions are treacherous and evil. Herla is punished for having anything to do with the fae. In medieval times, the story got repurposed. The land of joy and immortality was replaced by a Christian Paradise. Often, the hero of this story was a monk or bishop. The story was used to illustrate the idea that Heaven is so wonderful that a thousand years there are like three minutes, and earthly life is nothing compared to it. The main character would return long enough for people to confirm his identity and be amazed by the miracle, before he disintegrates and joyfully returns to Heaven for good. The main idea of the story is that eternity will not be boring, an issue which has apparently nagged at people for a long time. Versions appeared in English, Spanish, Slovenian, you name it. A fourteenth-century Italian legend featured four monks who, like Bran, went off seeking Paradise after finding a wondrous tree branch from that location (MacCulloch, Medieval Faith and Fable, p. 199). The most widespread version, where a bishop is entranced by the song of an angelic bird, appeared in a homily by the 12th-century French bishop Jacques de Vitry. At the same time, interestingly, the story has survived with fairy roots intact. For instance, a Welsh story of a farmboy who sits under a tree listening to a bird’s entrancing music parallels the story of the bishop. Despite the similarities, it's clear that the bird in the Welsh fairytale is from a very different otherworld than Heaven. (Howells, Cambrian Superstitions) Hans Christian Andersen may have been particularly inspired by something close to home: the Danish tale of "The Aged Bride." Published in Benjamin Thorpe's Northern Mythology (1851), it follows a bride who steps out of a dance at her wedding and notices elves celebrating in a nearby field. When she approaches, they offer her wine and invite her to join in their dance. Completing the dance, she remembers her husband and hurries home. There, however, she finds herself in a situation identical to Helga's, Urashima's, and Rip Van Winkle's. The wedding party has vanished and the town looks completely different. No one recognizes her except as an old story from a hundred years ago. Upon hearing this, she falls down dead. Compared to this story illustrating the dangers of the fairy world, "The Marsh King's Daughter" is positively cheery. Further Reading

|

About

Researching folktales and fairies, with a focus on common tale types. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Writing in Margins

RSS Feed

RSS Feed