|

Years ago, I wrote a blog post on the inspirations behind Hans Christian Andersen's "Thumbelina" (1835), examining a theory that the characters were influenced by people Andersen knew. And then I wrote another one a few years after that, focusing on the imagery of tiny flower fairies, which plays a big role in this fairytale. I want to revisit it this topic again and explore a little more deeply. It's always interesting to get into Andersen's writing process because these have become such classic fairytales and there are many different aspects to his stories. "The Little Mermaid," for instance, can be read as a semi-autobiographical tale of unrequited love, but also as Andersen's response to the hyper-popular mermaid story Undine, and also taking influence from other mermaid tales and tropes.

In "Thumbelina," a woman wishes for a little girl, and receives exactly that from a witch. The thumb-sized heroine is then kidnapped by a toad and deals with various talking animals who all want to marry her, until she winds up among fairies exactly her size and finally finds acceptance. Jeffrey and Diana Crone Frank compared Thumbelina to Gulliver's Travels by Jonathan Swift (1726) and the short story Micromégas by Voltaire (1752). They also mentioned "the figure of a tiny girl" in one of Andersen's first successful publications, the 1829 story A Journey on Foot from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager. So far as I can tell, this character is the Lyrical Muse, a forlorn, melodramatic spirit of inspiration who appears to the narrator in Chapter 2. When the narrator tries to catch her, she shrinks into a tiny point and escapes through a keyhole. Similarly, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s stories “Princess Brambilla” (1820) and "Master Flea" (1822) both feature imagery of tiny princesses found sleeping inside lotuses or tulips. Hoffmann's work was widely popular in Europe, and in 1828, Andersen was part of a reading group named "The Serapion Brotherhood" after the title of Hoffmann's final book. There's also the Thumbling tale type. I'm sure Andersen came across many of these. There were the Thumbling stories collected by the Brothers Grimm, for instance. These actually do not have a lot in common with Thumbelina. There's the thumb-sized character, born from a wish, who's separated from his parents and swept off on an adventure, but the male Thumblings are typically more proactive and they ultimately return home to their parents. This is very different from Thumbelina, who never sees her mother again in the story, and whose story is something of a coming-of-age, concluding with her wedding and transformation of identity. These characters are also nearly always male. There are female Thumbling characters, but they've all been collected after Thumbelina, like a Spanish character I'd refer to as Garlic Girl (Maria como un Ajo, Cabecita de Ajo, or Baratxuri) and the Palestinian tale Nammūlah (Little Ant). It's more common to have tiny girl characters in other tale types. "Doll i’ the Grass," "Terra Camina," and "Nang Ut" are all examples of the Animal Bride tale, with their sister tales typically being about enchanted frogs, mice and so on. The Corsican "Ditu Migniulellu" is a variant of the Donkeyskin tale, a close neighbor to Cinderella. Thumbelina is the oldest example I've found of a female Thumbling character. Closer is "Tom Thumb," the first fairytale printed in English, and one of the earliest Thumbling variants we know of (depending when you date Issun-boshi). As I mentioned in my post on flower fairies, Tom Thumb was part of a wave of stories around the turn of the 17th century which transformed fairies into tiny, cute flower spirits, changed the face of the English concept of fairies, and has had far-reaching consequences pretty much everywhere. "Tom Thumb" is literary, like "Thumbelina." It gets into tiny detail, describing Tom's wardrobe of plant matter--a major part of the Jacobean flower fairy trope. He is the godson of the fairy queen and makes trips to Fairyland. This story really feels out-of-place among folk Thumbling tales, due to how altered it is - much like Thumbelina. And like Tom Thumb, Thumbelina gets detailed sequences describing her miniature life, like the way she uses a leaf for a boat. There's also a comparison in the way that Tom is accidentally separated from his parents when he's swooped up by a raven, while Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad. (For contrast, in a lot of Thumbling tales, the separation takes place when a human sees the thumb-child and tries to buy him.) The tiny, winged flower fairies whom Thumbelina meets are a direct descendant of the insect-sized, elaborately costumed Jacobean fairies that we meet in "Tom Thumb." Another Andersen tale, "The Steadfast Tin Soldier," also has a Tom Thumb-like bit where the main character is swallowed by a fish and freed when the fish is cut open for cooking. But in addition to Tom Thumb, there's a Danish story that Andersen may have encountered in some shape. This is "Svend Tomling," or Svend Thumbling, which was printed as a chapbook in 1776. Like Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, Svend Tomling is a literary tale. However, it's not focused on the cutesiness of the character; instead it's a lot more ribald, closer to the folk stories and veering off into satire. I'd really need someone fluent in Danish to give more in-depth examination, but my understanding is that like Thumbelina, Svend is created when a childless woman goes to a witch who gives her a magic flower. Thumbelina is kidnapped by a toad and carried off in a nutshell; Svend is bought by a man who carries him off in a snuffbox. Thumbelina escapes and rides away on a lilypad drawn by a butterfly; Svend escapes and rides off on a pig. More importantly, Svend Tomling has themes that are unusual for a Thumbling story - a lot like Thumbelina. He contemplates marriage and faces the prospect of unsuitable partners. Thumbelina's suitors are her size, but the wrong species; the human women around Svend are the right species, but the wrong size. Even Issun-boshi feels a little different; it is a romance, but it doesn't feel quite as focused on considering the dilemmas and false matches and societal issues. There is a whole sequence where Svend sits down and debates with his parents about how to find an appropriate wife. Thumbelina faces criticism of her looks, advice on how to marry, and generally societal pressure on how she as a woman should be living her life. Thumbelina and Svend aren't the only Thumblings to assimilate and transform to fit into society (Thumbelina gets fairy wings to live with the fairies, Svend grows to human scale), but it does feel really key. Thumbling stories are often about childhood, albeit exaggerated so that the main character is not merely small but infinitesimal. Most thumbling stories end not with the hero finding a place for himself or getting married, but with him returning to his parents, the place where he still belongs. Tom Thumb dies at the end of his story, leaving him forever a child. Stories like Issun-boshi, where the character literally grows up and gets married, are rarer. References

Other Blog Posts

2 Comments

You may have heard of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but have you ever heard of Svend Tomling?

Svend Tomling is the third oldest surviving thumbling tale, and is largely forgotten other than a few footnotes. Interestingly, its more famous predecessors, the Japanese Issun-Boshi and English Tom Thumb, are both fairly unique among thumbling tales. Issun-Boshi is one of the short stories and fairytales known as the Otogizōshi, written down mostly in the Muromachi period from 1392-1573. The exact date of Issun-Boshi's origin is unclear, but it's usually assigned to the 15th or 16th century. Japanese thumbling tales make up a unique subtype, with similarities to The Frog Prince. "Issun-boshi" is a romance in which a tiny, unassuming hero wins a princess for his bride, and then transforms into a handsome prince. The story still contains classic Thumbling motifs, and the story is surprisingly close to that of Tom Thumb all the way over in England. Issun-Boshi is born to an elderly couple who pray for a son; he uses a needle for a sword; he leaves home to serve an important nobleman. An oni, or demon, tries to swallow him, but Issun-Boshi escapes from his mouth alive. Tom Thumb is also of unclear original date, but at least we have dates for some important pieces of evidence. His name is mentioned in literature as early as 1579. A prose telling of the tale was printed in 1621, and a version in verse in 1630, although these are dated to the printing of the individual copy, not to the date of composition. The prose and metrical versions are very different, but hit most of the same beats. A childless couple turns to the wizard Merlin for help. Their son, who is born unusually quickly and of tiny size, wields a needle for a sword. He is swallowed in a mouthful of grass by a grazing cow, cries out from its belly, and is excreted. A giant tries to devour him. He is swallowed by a fish and discovered when someone catches it to cook it. He goes on to serve in King Arthur's court, then falls sick. Here the two editions diverge - the metrical version has him die of his illness and be grieved by the court, but the prose version has him recover when treated by the Pygmy King's personal physician, and go on to have other adventures including fighting fellow literary character Garagantua. Both of these stories are clearly thumbling stories, but they do not fit the usual map of Aarne-Thompson Type 700, a formulaic tale found consistently through Europe, Asia, the Middle East and North Africa. The Grimms were aware of this formula and actually published two thumbling stories. Their first was Thumbling's Travels, also a rather unusual example, but they later went back and added Daumesdick (Thumbthick, also translated as Thumbling), which better fit the pattern. A childless couple wishes for a son; he is only a thumb tall; he drives the plow by riding in the horse's ear, is sold as an oddity, escapes, has an encounter with robbers, is swallowed by animals, and finally returns home. Issun-Boshi, again, is part of a unique subtype. As for Tom Thumb, it's likely the subject of some literary embellishment, expanding a simpler traditional tale. Hints of the wider tradition peek through, like a scene where Tom returns home with a single penny and is welcomed by his parents. This is where many Type 700 stories end, but Tom Thumb instead keeps going. The traditional tale started really getting attention with the Grimms, but they were not the first ones to publish an example. The earliest surviving specimen is the Danish "Svend Tomling", or Svend Thumbling. Svend is a common men's name meaning "young man" or "young warrior," giving it the same generic feel as "Tom" in English. Both Svend Tomling and Tom Thumb essentially boil down to the same name of "Man Thumb," the way the name Jack Frost boils down to "Man Frost." Svend Tomling appears to have been the generic name for a thumbling in Denmark; it was also used for a Hop o' My Thumb type, which is an entirely different tale. The relevant version is a 1776 booklet by Hans Holck. It drew attention from the Danish historian Rasmus Nyerup, and from the Brothers Grimm. Nyerup, in particular, remembered reading or hearing the story as a child. The translation I've been working on is admittedly choppy, and I take responsibility if it's in error. "Svend Tomling" begins, as most thumbling stories do, with a childless couple. The wife goes to visit an enchantress and, upon instruction, eats two flowers. She then gives birth to Svend Tomling, who is born already clothed and carrying a sword. The section that follows is almost exactly the classic thumbling tale, with some unique details. Svend helps out on the farm by driving the plow, sitting in the horse's ear. A wealthy man witnesses this, purchases him from his parents, and carries Svend away (specifically, keeping him in his snuffbox). Svend escapes. Falling off their wagon, he lands on a pig's back and begins riding it like a horse. However, he is attacked by wild animals, and eventually the pig runs away. Lost in the middle of nowhere, Svend overhears two men plotting to rob the local deacon's house and asks to come along. He makes so much noise that he awakens the servants, and the thieves flee. There is a small divergence here, where the house owners think that Svend is a nisse (a Danish house spirit similar to the brownie) and leave out porridge for him. It doesn't take long before Svend is accidentally swallowed by a cow eating her hay. He calls out from inside her stomach to the milkmaid, who is frightened and thinks the cow is bewitched. Here's another divergence: people take this to mean that the cow can foretell the future, and flood to visit. This introduces a long monologue from a priest complaining about the peasants. Ultimately the cow is slaughtered. A sow eats the stomach in which Svend is still trapped, then poops him out. He falls into the water, where his own father happens to hear him crying out for help, and takes him home to recover. So far the plotline has been generally typical, but at this point, the story strikes out in its own direction. Svend announces that he wishes to take a wife. In particular, he wants to marry a woman three ells and three quarters tall. The length of an ell varied by country, but in Denmark, it was considered 25 inches. Svend Tomling is speaking of a wife who would be something like seven feet tall. His parents try to dissuade him, saying that he's far too small, and Svend grows frustrated. He begins bothering a "Troldqvinden" (a troll woman or witch) until she gets angry and transforms him into a goat. His horrified parents beg her to have mercy, and she relents and changes him into a well-grown man. The rest of the booklet (four pages out of the whole sixteen!) deals with Svend and his parents discussing his future, with questions of choosing an occupation and a bride, as he sets off into the world. Rasmus Nyerup took a pretty dim view of this story, remarking that great liberties had been taken with the folktale he remembered - particularly the priest's long speech about the problems with peasants, which has nothing to do with Svend Tomling. I suspect that the disproportionately long section on life advice is also original. The motif of eating two flowers and then giving birth to an unusual child is striking. This is exactly what happens in the story of King Lindworm (also Danish), where the resulting child is a lindworm and must be disenchanted. Also in Tatterhood (Norwegian), the queen who eats two flowers gives birth to a daughter, just as precocious as Svend, who rides out of the womb on a goat and carrying a spoon. Tom Thumb is usually listed as an influence on Hans Christian Andersen's Thumbelina. However, I think Svend Tomling might have been a stronger influence. If Rasmus Nyerup heard the story as a child, Andersen might have too. Both Svend Tomling and Thumbelina begin with a childless woman visiting a witch for help. Svend's mother eating flowers to conceive hearkens to Thumbelina being born from a flower. Both Svend and Thumbelina focus on the question of the character finding a fitting mate and a society that they fit into. Svend, like Thumbelina, is faced with incompatible mates, although for him these are ordinary human women, and for her, talking animals. Ultimately, otherworldly intervention transforms them to fit into their preferred society. Svend goes to a troll woman who makes him tall enough to seek a bride, while Thumbelina marries a flower fairy prince and gains wings like his. (Actually, Issun-Boshi did this too, getting a magical hammer from an oni and growing to average height.) Overall, Thumbelina has more in common with Svend Tomling and even Issun-Boshi than she does with Tom Thumb. The story itself is not all that great, but it does provide one of our earliest examples of the Thumbling story - and casts light on the others that followed. Sources

In 1835, Hans Christian Andersen published his fairytale “Tommelise,” or Thumbelina. A childless woman seeks help from a witch and receives a barleycorn. When planted, it grows into "a big, beautiful flower that looked just like a tulip" with "beautiful red and yellow petals." When it opens: "It was a tulip, sure enough, but in the middle of it, on a little green cushion, sat a tiny girl."

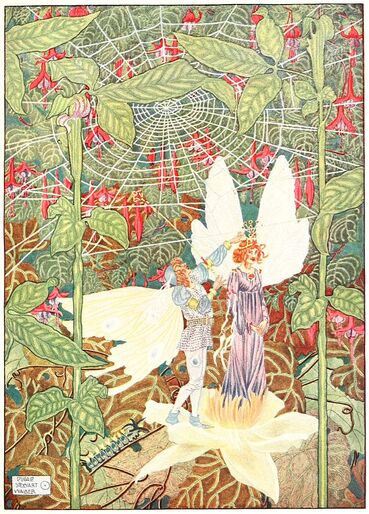

In "Thumbelina," Andersen took loose inspiration from older thumbling tales, but the heroine's birth from a flower is unusual. Some thumblings are created from a bean or other small object, but most often he or she is apparently born in the normal way, through pregnancy. Why did Andersen choose to write Thumbelina born from a flower - and what is the tulip's significance? Flower Fairies There's a widespread motif of fairies living in flowers. Andersen would have been well-aware of this trope. Thumbelina later encounters flower-angels (blomstens engels). They are evidently not quite the same species (winged and clear like glass, and dwelling in white flowers), but Thumbelina is happy enough to settle down with them. Another Andersen story, "The Rose Elf" (1839) also deals with tiny flower-dwelling spirits. The tiny flower fairy became popular around 1600. Shakespeare was an important influence; A Midsummer Night's Dream elves creep into acorn-cups to hide, and The Tempest's Ariel sings of lying inside a cowslip bell. In the anonymous play The Maid's Metamorphosis, a fairy sings of "leaping upon flowers' toppes". In the 1621 prose version of Tom Thumb, Tom falls asleep "upon the toppe of a Red Rose new blowne." In the 1627 poem Nymphidia, Queen Mab finds a "fair cowslip-flower" is a "fitting bower." What about older versions of the flower fairy? Greek mythology included dryads and other nature spirits, including the anthousai, or flower nymphs. Before Shakespeare, fairies in legends were generally child-sized at smallest - there are exceptions, such as the portunes of Gervase of Tilbury. Fairies, witches and other spirits were often said to ride in eggshells or crawl through keyholes. Fairies were held to live in nature and dance in "fairy circles" made of mushrooms or grass, or were encountered beneath trees. I'm also reminded of a 6th-century story recorded by Pope Gregory the Great, where a woman eats a lettuce which turns out to contain a demon. The demon complains, "I was sitting there upon the lettice, and she came and did eat me." Superstitions held that demons might take up residence inside food if it wasn't properly blessed or protected with charms. Cowslips and foxgloves, already mentioned, were old fairy flowers. Cowslips are also known as fairy cups (Friend, Flower Lore), and foxgloves are fairy caps or as menyg ellyllon (goblin gloves). But these suggest very different scales. Flowers are hats and cups in language, but houses in literature. Katharine Briggs argued that Shakespeare did not originate the tiny flower fairy, but was inspired by contemporary tradition - however, there's not much evidence for this. Diane Purkiss took the exact opposite point of view, deeming it "questionable whether Shakespeare knew anything about fairies from oral sources at all," but I think this is an unnecessary leap. In more of a middle ground, Farah Karim-Cooper suggested that Shakespeare actually rescued fairies. In contemporary culture, they were being demonized, grouped with devils and witches and sorcery. Shakespeare made them benevolent but also tiny, therefore harmless and acceptable. In 1827, Blackwood's Magazine talked about Shakespeare's fairies and how they would "lodge in flower-cups, a hare-bell being a palace, a primrose a hall, an anemone a hut." I do not recall seeing these specific examples in Shakespeare, but this was now the popular perception. In the first 1828 edition of The Fairy Mythology, Thomas Keightley also talked about "the bells of flowers" as fairy habitations. "Oberon's Henchman; or the Legend of the Three Sisters," by M. G. Lewis (1803) describes fairies "Close hid in heather bells". In the poem “Song of the Fairies,” by Thomas Miller (1832), the fairies "sleep . . . in bright heath bells blue, From whence the bees their treasure drew," and then just in case we missed it, their "homes are hid in bells of flowers." Later in the same volume, a fairy named Violet "in a blue bell slept." Hartley Coleridge wrote of "Fays That sweetly nestle in the foxglove bells” (Poems, 1833) and Henry Gardner Adams had "The Elves that sleep in the Cowslip’s bell" (Flowers, 1844). The wood anemone was another fairy flower; at night the blossoms curled over like a tent, and "This was supposed to be the work of the fairies, who nestled inside the tent, and carefully pulled the curtains around them." (The Everyday Book of Natural History, 1866) This implies the existence of another explanatory legend. In a paper presented at a meeting of the New Jersey State Horticultural Society - yes - and published in 1881, the writer reminisced "I remember how I enjoyed the imaginary exploits of the little fairies that had their homes in these flowers. I had always thought it a pretty conceit to make the fairies live in flowers, but never thought how near the truth it is" . . . And then comes a leap to microorganisms. "A flower is a little universe with millions of inhabitants." Children's literature at the time was focused on edifying, providing morals, and providing scientific education. Fairy stories were considered a natural interest for children, and so they were often used to dress up school lessons, particularly on the natural world. They were a perfect way to launch into a lesson on insects or the world that could be found through a microscope. What about tulips specifically? David Lester Richardson's Flowers and Flower-Gardens (1855) mentions that "The Tulip is not endeared to us by many poetical associations." On the other hand, writing a century later, Katharine Briggs believed that the tulip was "a fairy flower according to folk tradition" and that it was a bad omen to cut or sell them. Taking a step back: in European thought, after the crash of the Dutch "tulip mania" in the 1630s, tulips generally became symbols of gaudiness and tastelessness, particularly in superficial female beauty - for instance, Abraham Cowley in 1656 writing "Thou Tulip, who thy stock in paint dost waste, Neither for Physick good, nor Smell, nor Taste." (Rees). As time passed, this faded into the background, but was not forgotten. David Lester Richardson wrote that tulips had remained extravagantly expensive, even in England, as late as 1836. There are a couple of 18th-century examples of tulip fairies. Thomas Tickell's poem "Kensington Garden" (1722) speaks of the fairies resembling a "moving Tulip-bed" and taking shelter in "a lofty Tulip's ample shade." In 1794, Thomas Blake's poem "Europe: A Prophecy" described a fairy seated "on a streak'd Tulip," singing of the pleasures of life. Intriguingly, in the same decade as Thumbelina, an early English folklorist named Anna Eliza Bray collected a story which also featured fairies within tulips. She recorded it in 1832 and published it in 1836, in A Description of the Part of Devonshire Bordering on the Tamar and the Tavy. The story follows an elderly gardener who discovers that the pixies have begun using her tulilps as cradles for her babies. She eventually dies. Her heirs rip up the flowerbed to plant parsley, but find that none of their vegetables will grow there. Meanwhile, the gardener's grave always mysteriously blooms with flowers. Bray does not give a specific source, other than to speak briefly of gathering the tales from village gossips and storytellers, with the assistance of her servant Mary Colling. Bray's pixie story was retold in fairytale collections and books of plant folklore. When she published a children's book, A Peep at the Pixies (1854), most of her focus in the introduction was on pixies’ small size relative to children; they could "creep through key-holes, and get into the bells of flowers." By the 20th century, the tulip as fairy flower was set. James Barrie wrote in The Little White Bird (1920) that white tulips are "fairy-cradles" (158), and Fifty Fairy Flower Legends by Caroline Silver June (1924), reveals that “Fairy cradles, fairy cradles, Are the Tulips red and white." Folklore In fact, fairies were not the only denizens of plants in legend. Birth from plants is very common in fairytales. English children were told that babies might be found in parsley beds, while in Germany, infants were more likely to be found among the cabbages or inside a hollow tree. (Curiosities of Indo-European Tradition and Folklore) In a French version, baby boys were found inside cabbages, baby girls inside roses. (e.g. Revue de Belgique, 1892, p. 227) Gooseberry bushes were also a likely spot. In Hindu culture and mythology, saying someone was born from a lotus was a way to indicate their purity. In Japanese stories, baby Momotaro is found inside a peach, and Princess Kaguya inside a bamboo. The Indian tale "Princess Aubergine" has a girl born from an eggplant. In the Kathāsaritsāgara (Ocean of the Streams of Stories), an 11th-century collection of Indian legends, Vinayavati is a heavenly maiden (divyā-kanyakā) who is born from the fruit of a jambu flower after a goddess in bee-form sheds a tear on it. In the Italian tale of "The Myrtle", from the Pentamerone (1634-1636), a woman gives birth to a sprig of myrtle. A fairy (fata) emerges from the plant each night, and a prince falls in love with her. However, the heroine is apparently of human scale, although she inhabits a plant not unlike a genie in a lamp. Later folklorist Italo Calvino collected more variants: "Rosemary" and "Apple Girl." The woman or fairy hidden within a luscious fruit appears in tale types such as "The Three Citrons." With the first known example of this story in The Pentamerone, there are probably as many variants of this story as there are types of fruit. In a close fairytale neighbor, a mother eats a flower to become pregnant - see the Norwegian "Tatterhood," the Danish "King Lindworm," and "Svend Tomling." "Tom Thumb" is usually cited as an influence on Thumbelina; in this story, a childless woman consults Merlin for help. Merlin prophesies her child's fate, she undergoes a very brief pregnancy, and then gives birth to a child one thumb tall. However, the two stories have little in common; the Thumbling tale type is widespread, and Andersen may have been inspired by other examples. The most likely candidate is "Svend Tomling," a chapbook written by Hans Holck and published in 1776. My translation is very choppy, but I think the gist is that a childless woman consults a witch. The witch causes two flowers to grow and instructs the woman to eat them. The woman then gives birth to Svend, one thumb high and already fully dressed and carrying a sword (beating out Tom Thumb, who has to wait several seconds for his wardrobe). I don't know for sure if Andersen knew this story, which hasn't achieved quite the same ubiquity as Tom Thumb. However, the fact that it was from his own country, and the similarities in Svend Tomling's and Tommelise's births, make a relationship seem likely. E. T. A. Hoffmann Fairytales weren't Andersen's only inspiration. One of his major influences was the fantasy/horror author E. T. A. Hoffmann (creator of The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, among other things). In Hoffmann’s “Princess Brambilla” (1820), a fairytale-esque subplot has the magician Hermod tasked with finding a new ruler for the kingdom. He causes a lotus to grow, and within its petals sleeps the baby Princess Mystilis. The person-inside-flower motif recurs throughout the story. Mystilis is later placed in the lotus to break a curse that has fallen on her, and emerges the second time as a giantess. Hermod himself is frequently seen seated inside a golden tulip. “Master Flea” (1822) has similar imagery. A scholar, studying a "beautiful lilac and yellow tulip," notices a speck inside the calyx. Under a magnifying glass, this speck turns out to be Princess Gamaheh, missing daughter of the Flower Queen, now microscopic and fast asleep in the pollen. Conclusion Andersen created his own thumbling tale inspired by folktales like that of Svend Tomling. However, he wove in plenty of elements in his own way - such as talking animals, or a girl born from a tulip. His work, including both "Thumbelina" and "The Rose-elf," shows the contemporary interest in fairies who lived inside flowers. Andersen's fairies in particular are most like personifications of plants. In the past, tulips had gained a bad reputation, becoming symbols of shallow frippery. However, by the time Andersen wrote, the disastrous tulip fad had had time to fade into history a little more. Instead, tulips started to be mentioned occasionally with fairies. In the 1800s, one author might have noted tales of tulip fairies as rare. However, a century later, Katharine Briggs could categorize it as a fairy flower. What changed? The most important thing may have been new associations for the tulip's shape; it was grouped in with other flowers that resembled bells or cups. I was startled when I went looking for examples of flower fairies - I occasionally found descriptions of them resting on top of the flowers, like Tom Thumb. However, more often than anything, I found the word "bell." Heather-bells, foxglove-bells, cowslip-bells, bluebells, bell-shaped flowers. In 1832, Thomas Miller's flower-fairy poem used the word bell three separate times. With fairies increasingly shrunken around Shakespeare's time, flowers that would have once been cups or hats were instead envisioned as houses or hiding places for fairies. The shape does suggest that something could be tucked inside, and lends itself to an air of mystery. Storytellers, including Andersen, focused on the idea of the hidden observer. Mary Botham Howitt wrote in 1852 "We could ourselves almost adopt the legend, and turning the leaves aside expect to meet the glance of tiny eyes." (George MacDonald used similar images, although with a more sinister slant, in his 1858 book Phantastes.) However, although Thumbelina's birth is still tied to the idea of flower fairies, it has more in common with tales of heroes born from plants. It is also strikingly reminiscent of E. T. A. Hoffmann's short stories; Hoffmann wrote twice of tiny princesses discovered inside flowers. In his work, tulips were not just gaudy or overly expensive, but had esoteric and mystical associations. His characters may be Thumbelina's clearest literary ancestors. Further Reading

Thumbelina, or Tommelise, was first published in 1835. An author may be inspired by many things, not all of them obvious. One theory is that the character of Thumbelina was inspired by a close friend of Hans Christian's Andersen's: Hanne Henriette Wulff, known to friends as Jette (1804 -1858). Andersen considered the Wullfs close family friends. The oldest daughter of the family, Henriette was tiny, frail, and slightly hunchbacked. She became one of Andersen's most faithful penpals, and their letters are one of the main sources of information about his life. She also helped translate some of his work to English. They seem to have had a close platonic relationship, and Andersen would portray her in his autobiography as almost his muse. The theory that she inspired Thumbelina is seen in works such as Opie's Classic Fairy Tales (1974) and Houselander's Guilt (1951). Many of Andersen's fairytales were inspired by older folklore, and there was a wealth of thumbling stories that he surely drew on for Thumbelina. Tom Thumb was famous, of course; there were also the Thumbling stories of the Brothers Grimm collection, and Danish variants such as Tommeliden or Svend Tomling. Thumbelina's opening sequence, with the lonely woman longing for a child, could be straight out of one of these tales. There were plenty of other works containing tiny people which could have inspired Andersen. As listed by Diana and Jeffrey Frank, Andersen would have been familiar with Gulliver's Travels (1726), Micromégas by Voltaire (1752), and E.T.A. Hoffmann's works "Meister Floh" (1822) and "Prinzessin Brambilla" (1820). The image of a tiny girl also appeared in Andersen's previous work and first real literary success, A Journey on Foot from Holmen's Canal to the East Point of Amager (1828). According to the Franks, there is no evidence that Thumbelina was based on Henriette. They do suggest, however, that the character of the learned but literally and metaphorically blind mole was inspired by Andersen's former teacher, Simon Meisling. Meisling was a short, overweight man who apparently did look somewhat like a mole. He repeatedly told Andersen that he would never make it as an author, calling him a stupid boy. SurLaLune also compares Thumbelina's beautiful singing voice to that of Andersen's friend, the famous singer Jenny Lind. Andersen and Lind met in 1843. In Hans Christian Andersen's Interest in Music, Gustav Hetsch and Theodore Baker assert that Lind inspired "The Nightingale," "The Angel," and "Beneath the Pillar." Another biographer, Carole Rosen, suggested in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography that Lind inspired "The Ugly Duckling" and that her rebuffing of Andersen's affections influenced the icy-hearted Snow Queen. That last one is kind of a leap. The tale that is most likely connected to Lind is "The Nightingale." The Franks mention that right after Andersen saw her perform and visited Tivoli Gardens, which had an "Asian fantasy motif," he started the Nightingale and made note of it in his diary. He finished the story in two days (pg 139). Afterwards, as Lind grew world-famous, she was known by the nickname "The Swedish Nightingale." The Franks also say that Andersen's bleak tale "The Shadow" was aimed at a friend named Edvard Collin who had snubbed him years before (pg 16). Andersen undoubtedly drew on his experiences and the people around him for inspiration. It's entirely possible that aspects of the mole were inspired by Simon Meisling, some part of Thumbelina by Henriette Wulff, or the sweet song of the Nightingale by Jenny Lind. However, a lot of that has to remain speculation.

As for more on Henriette Wulff: she loved travelling and the sea, visiting such places as Italy, the West Indies, and the United States. After her parents' death, she lived with her brother until he died of yellow fever. She returned to Denmark, but strongly considered emigrating permanently to America, where her brother was buried. In 1858, she embarked for New York on the SS Austria. Twelve days after her departure, on September 13, there was an accident with fumigation equipment, and the ship's deck burst into flames. Passengers leaped into the sea to escape the roaring fire that engulfed the entire ship. Out of the 542 people aboard, 449 perished. Henriette was among the dead. In a poem dedicated to her, a grieving Andersen called her sister. Sources

Tom Thumb and Thumbelina are closely associated in pop culture, for obvious reasons. They've starred together in two direct-to-video movies. They appear as a couple in Shrek 2. I've also found mistaken statements that General Tom Thumb's wife used the stage name Thumbelina.

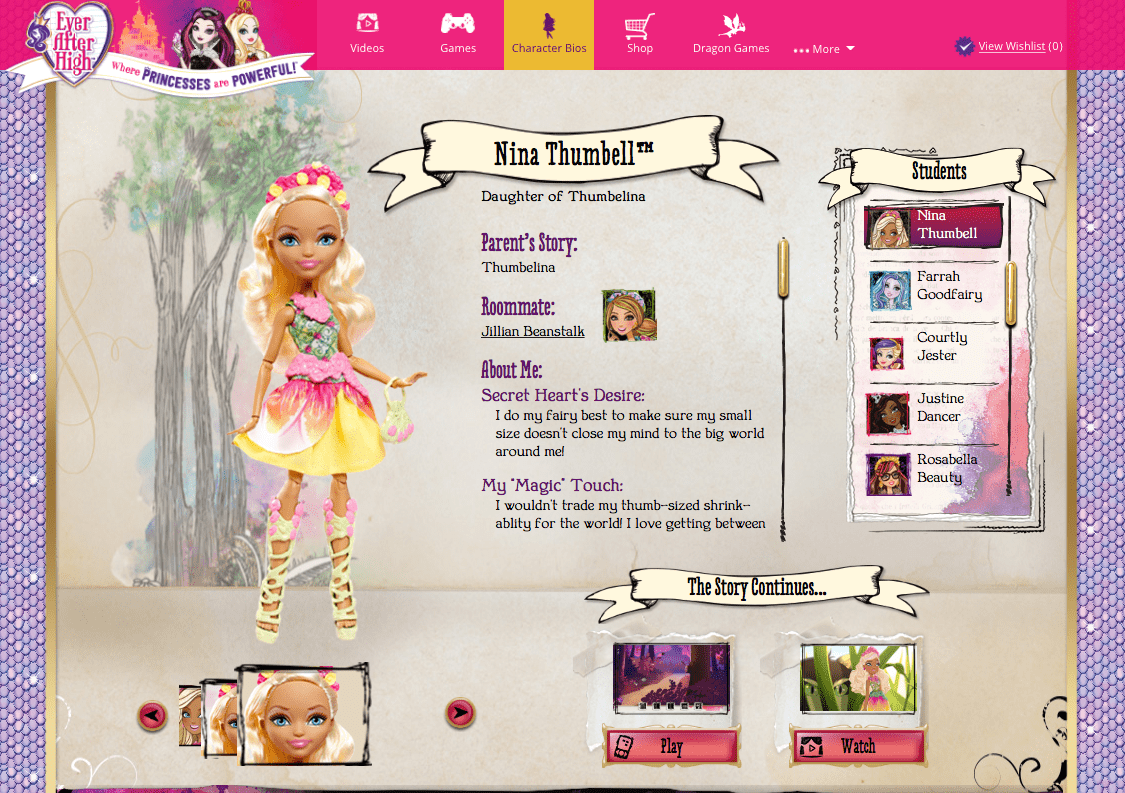

It's interesting to see how these crossovers treat the characters. The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina was basically just a retelling of Thumbelina; despite getting first billing, Tom was barely the deuteragonist and bore no resemblance whatsoever to his original fairytale. Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina seems like it took inspiration from both fairytales, but otherwise just kind of . . . does its own thing. In a Nutshell, by Susan Price, is a fairly short book published in 1983. It can be a little hard to find in libraries. The main characters, Thumb and Thumbling, are a pair of tiny fairies who anger King Oberon. As punishment, he takes away their powers and gives them to human families. However, the tiny man and woman decide to find each other and get back to Fairyland - which is a tall order for a couple of people only two inches tall. It's one of the most interesting mashup of thumbling tales I've read. Though Thumb is (like Tom Thumb) based in England, and his parents use that name once, his adventures of riding in a horse's ear and being used to fetch stolen goods for robbers are all Thumbling. Thumbling, given to a lonely woman in Denmark, is Thumbelina, and the quest and conclusion are strongly based on The Young Giant. The characters are unlikeable. They're supposed to be unlikeable, as fairies are played up as uncompassionate creatures, but it's still hard to get invested when they act as callous as they do. They only start to come around and grow into better people near the end. One touch I liked was how much we see the danger of their lives; Price does a pretty good job of making it feel like they are constantly threatened. Even their adopted parents could easily harm them, and overpower them by far. I don't think this book is going to be remembered as a classic or anything like that, but it was an interesting read, and I have it on my bookshelf now. You don't see thumblings in pop culture that much, so I take an interest whenever anyone does adaptations. I collect dolls, and one of my Christmas presents this year was an Ever After High doll: Nina Thumbell. Ever After High is a doll franchise by Mattel. The basic concept is that the dolls are all the children of fairytale characters. One day, they're all supposed to live out the fairytales like their parents before them, but some of them rebel against this idea. As you may have already guessed, Nina is the daughter of Thumbelina. No, the doll is not thumb-sized. This character can magically grow and shrink. More on that later. I have mixed feelings on her fashion sense. I like how her skirt resembles a tulip, but the plaid shirt is kind of weird, and my mom remarked that her vine boots looked like green silly string. Seeing the doll in person, the color combo is growing on me. I also like that the face molds are now more unique and expressive, although in other areas the new dolls lack the small details that appeared with older dolls. (For instance, the box doesn't include a doll stand as the older ones did, and Nina lacks the earrings that she wears in promo art.) I will say she is very fun to pose. Unlike the other dolls, Nina's box does not include a diary, but has only a small card bearing a brief description.

The lack of a diary was the one thing that really disappointed me when I opened the box. Nina does appear as a cheerleader in the diary of another character, Faybelle Thorn, and in one of the tie-in books, Fairy's Got Talent by Suzanne Selfors (2015). She isn't really fleshed out there, but seems mainly cautious and fearful and tends to go with the flow. This contrasts with her fearless characterization in other media. She is allied with the Rebels, the faction thats want to throw off their destinies, rather than the Royals, who want to follow in their parents' footsteps. She really only gets a spotlight once, in her webisode Thumb-believable. The other characters shrink down to her size so that she can give them a tour of Ever After High as she sees it. There are some pretty fun scenes where they climb through the walls and enter Nina's room, which appears to be inside a locker. She loves exploring and has a pet cat.

What does that mean?

In this aspect, Nina is like the "animal" characters (like the Cheshire Cat's and White Rabbit's daughters) who can turn into human form. These are characters that are marketed as dolls - not, notably, the Three Little Pigs or the Billygoats Gruff. A proportional Nina doll would be a tiny speck, not really a great doll to play with. However, her power kind of breaks the story. It's hard to see how the challenges Thumbelina faces would be challenges if she could shoot up to five foot three at any time. One person on a fan wiki suggested this was because of Nina's fairy heritage from her father, which I thought that was clever.

Because her fairytale's about people trying to force her into marriage

A short joke, but also suggests a side of her that hasn't been seen yet.

Because she's a flower fairy.

Another short joke.

And that's about all there is to know about Nina Thumbell at this point. Unfortunately, considering the direction Ever After High has been going recently, I'm concerned that we may not see much more of its characters, including Nina. I'd love to see more books featuring her.

Katanya is a Jewish tale from Turkey, collected in the Israel Folklore Archives and later published in English in a couple of books. It also recently inspired a music composition. Although the story is sweet, it doesn't have much of substance. It is Thumbelina if you subtracted out the entire plot and skipped directly from Thumbelina's birth to her meeting the prince. I'm not a huge fan of what Thumbelina's plot is, but it exists. The Thumbelina story is an episodic one, featuring multiple bridal kidnappings. The main character has little agency, and is used and judged by one group after another. Her mother and the mysterious fairy are non-entities who disappear quickly from the story. All the other women are negative forces. The female toad and mouse force her into marriage with kidnapping and physical threats (the mouse threatens to bite Thumbelina), and the female beetles brutally mock her appearance and reduce her to tears. The plot of Katanya is basically "Old woman is sad because she has no children. Old woman gets everything she wants." And it's adorable and has positive depictions of women, but it's not particularly exciting. Katanya starts out with the Prophet Elijah showing up to give some dates to a lonely, childless, old woman, and I have to stop here because the fact that it's Elijah is AWESOME. According to the notes, Elijah and King Solomon are the two most popular stock figures in Jewish folktales, and Elijah stories frequently feature him being sent by God to help people in need. Katanya means "God's Little One" and sounds familiar because of another tiny character - K'tonton, whose name means "very little," first appearing in 1930 in short stories and books by Sadie Rose Weilerstein. Like Thumbelina, Katanya is closely associated with sunlight. Thumbelina is born from a flower, loves the sunlight, and goes to live in a summery land of flowers. Katanya is born from a date after it sits in the sun for a while, and she is dressed in shining clothes the color of a rainbow.

Her story is very domestic, dwelling on food and chores such as cleaning the house and sewing dresses. It's a short story and the greater part of it is simply her and her mother doing things together. Katanya's two most memorable traits are her industriousness (one of the first things she does is make a broom for herself out of straw) and her singing, which brings joy to everyone who hears it. She is the model of a good daughter. The beautiful singing voice is a trait she shares with Thumbelina; their voices attract their mates to them. Katanya's prince apparently doesn't care how small his wife is. As in Three-Inch, the tiny hero doesn't need to change. Unlike Three-Inch, Katanya's small size is barely even brought up as a possible problem and the prince mentions it only in passing. Contrast Thumbelina. The fairies are the closest to her "own" kind that she ever finds, but she must still go through a transformation to be with her husband, receiving wings and a new name. Thumbelina goes away from her mother and likely never sees her again. A swallow carries her to a far-off country to meet her prince. Katanya is never separated from her mother, who is, in fact, the one who carries her to the prince. Her mother implicitly blesses their marriage and lives with them in the palace. She has gone from being poor and alone to having a child who is now an adult and can care for her in her old age. Notably, neither heroine has any kind of father figure. Katanya's mother is a widow. For all its flaws, Thumbelina has a more dynamic plot and is more interesting as a story. Katanya's narrative is less dramatic and puts no obstacles in the main characters' paths. It's about a woman and her young daughter and their everyday household life. It ends when the daughter becomes a woman herself and takes her now-elderly mother into her new household. It feels like an average life story, save for the detail of Katanya's size. SOURCES

I’ve read some pretty thorough reviews of this movie, to the point where I questioned whether to review it myself. But I started watching it, and hoo boy. First of all, I have to say, the animation is technically superior to Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina, but this is still one weird-looking and ugly movie. The voiceover explains how a man from a circus discovered a kingdom of tiny people, and stole two small children. This seems badly thought out. I’m not sure how you would take care of a baby that small. I guess people raise baby bats and things like that. But how come he never went back? It’s too profitable to forget about. I need more information, movie. Years later, Thumbelina’s now a young woman. She’s grown up in this guy’s circus and we see her prepare for and perform a show in which she does acrobatics alongside a trained monkey and mouse. I’m questioning how everyone seated in the audience can really have a good view of a mouse and a six-inch-tall girl performing from that distance. (I think the ringmaster mentions that she’s six inches tall, which is not exactly thumb- or mouse-sized, but we’ll also see later scenes where she is definitely finger-sized, i.e. no more than three inches tall. Continuity is not this movie’s strong suit. In the first scene, Thumbelina switches from nightgown to day clothes to a different nightgown.) A note: this movie is set in modern times. The show features a King Kong pastiche complete with skyscraper and plane. Anyway, it’s a fairly good success. Thumbelina returns to her dollhouse and we get a pretty good song from her. Not because of the lyrics, though. “My heart breaks into two or maybe three”?? It does remind me of the song in Don Bluth’s Thumbelina. It’s about wanting to find love and ends with her at a window. Now, at last, we meet Tom, who is fixing a car. He lives with an old man named Ben and three extremely ugly dogs. The two talk about the night he found Tom, and the conversation soon turns sad, as Ben sends Tom out into the world to find his own path. “I’m old and dying. LEAVE. And find love, okay, but leave.” What about the dogs, though? Is he going to send them off on quests of self-discovery too? Meanwhile, the ringmaster nails Thumbelina’s dollhouse shut and leaves it in the dark under a blanket, on the animal cart. And, 15 minutes into the movie, the animals start talking. I think this is something that should have been introduced earlier. Thumbelina might too, as she seems surprised. Did she know that animals could talk? Anyway, she KICKS DOWN THE DOOR – you go, girl – and manages to rappel, jump and bounce to freedom. We soon see her seated by a stream, where she briefly encounters a horribly badly drawn frog. Little does she know that she’s almost right next to Tom Thumb. (Tom’s carrying a compass. He has a compass? There are miniature compasses that will fit in a backpack that size?!) The next day, Thumbelina keeps strolling along, only to be interrupted by some beetles who follow her and keep insulting her. She boats off in what looks like a sardine tin. Meanwhile, some moles tunneling along at high speed notice her. Tom hears her humming and follows the noise, but he’s knocked off his feet by the moles. Twice. The two moles return to the Mole King’s kingdom. Why do moles find a human girl beautiful? Anyway, they do, and tell him she would make the perfect bride. I actually have a hard time finding this guy threatening, but he is set up as a terrifying villain with a Hulk-level temper. Part of it is that he’s blind, and actually everyone has gotten sick of him to the point that his entire kingdom now consists of him and just two servants. Strangely, the minions are dead-set on convincing him that he’s still a powerful ruler with many courtiers. One mole switches into a maid costume, but I don’t know why. He literally just ran to the other side of the room and put on a costume in full view. There is no point to the costumes other than an unfunny joke. A minute later, they’re shaking hands with imaginary people and talking to thin air, and the king’s completely fooled. Oh, and his throne is a shoe. Elsewhere, Thumbelina and Tom happen to sit on opposite sides of the same tree. Hearing the moles approach, they bump into each other and immediately RUN AWAY. What—but—that’s why they were out looking around! They were looking for others like them! Why would they scream and run away from each other? Tom apparently is thinking the same thing, and turns around to go get her. However, Thumbelina glares at him, and then tackles him. Though her head’s really huge in a couple of these shots, she looks like she’s about to slug him. But she cheers up when she hears he’s also looking for little people. That’s the same thing she’s doing! Then why did you run away and then attack him?! They’re soon chatting happily with each other about their pasts. They agree to team up, only to then be interrupted by the bugs, who have brought their mother. She thinks Tom’s cute but they make fun of Thumbelina’s name. Tom laughs too OH THANKS TOM And we learn that our two main characters, who have been bonding after finally finding someone else like them, haven’t even learned each other’s names yet!! They argue over whose name is sillier, she insults his height, he calls her rude, and where is this going? Why are they fighting? The mother bug tells Tom, “I don’t think there’s magic in this relationship.” OH SURE This is so stupid. Thumbelina has her back turned. Tom’s struggling and grunting as they’re hold their hands over his mouth, but she just assumes he doesn’t like her. She doesn’t even look back before storming off! Tom gets free, runs after her, and tells her she’s his friend. It’s like watching small children interact. Then he turns the other way as he asks her to come with him. On cue, the moles grab her. And he assumes she just wasn’t interested in hanging out! THESE PEOPLE. The Mole King is smitten with Thumbelina and starts planning their wedding on the spot. Thumbelina refuses because “there’s someone else” YEAH SOMEONE YOU DON’T GET ALONG WITH HALF THE TIME Tom returns to the bugs, who are bringing him food when they throw in Thumbelina’s shoe that fell off when she was kidnapped. He recognizes it immediately because who else wears Size -60 shoes? He finds the moles’ hole right away and knows what’s going on. Why? He hasn’t even met the moles. For all he knows Thumbelina’s shoe just happened to fall off. But then a huge shadow comes over all of them, they scream, oh dear As the Mole shows Thumbelina around, she looks in one of the holes and sees a blue bird tied up, so she goes in that one. YOU DON’T KNOW THAT BIRD THUMBELINA STRANGER DANGER STRANGER DANGER Thumbelina’s untying her when they overhear the moles planning to make “sparrow quiche.” (Aren’t sparrows normally brown?) Thumbelina jumps on the sparrow’s back and they get out, somehow, through a back way we didn’t see before. The sparrow, Albertine, reveals that she can’t fly, having been imprisoned since chickhood. Those moles are really devoted to their quiche recipe. They’re probably using cheese passed down from their grandparents. The mole minions pursue them through the tunnels, until they jump up and land in a birds’ nest. The moles, meanwhile, are scared off by a warthog. I didn’t take this seriously when I first read a review. But it is real. There is actually a scene with a warthog. Are warthogs indigenous to this area? Is it just a wild boar? I don’t know. But this is a real scene. Thumbelina gets all coy about Tom and wants to go back and find him right away. She’s certainly changed her tune. But they’re interrupted when Thumbelina is also abducted by a giant shadow. Cut to her in an odd-looking laboratory filled with sad-looking caged mice. Her bottle is set right next to Tom’s and the bugs’, where they can look over the desk of a creepy little kid who’s preparing cotton balls with ether to kill his specimens. Thumbelina manages to break free and knock the kid out with his own ether. As they escape, she stops to free the mice. Outside, she and Tom join the procession of mice, who are … suddenly … carrying … food. Huh. The mice thank them and take them along to their village, where they’re greeted by others. These others don’t seem particularly surprised to see them, but do seem to know exactly what happened even though I didn’t see anyone explain the story. Okay, I want to step back for a moment and look at that weird little kid.

But anyway. Just for fun: compare the circus mouse to the wild mice. Don’t do drugs, kids. The mice declare a celebration, and one takes Thumbelina off to get dressed up. Which means basically, “Come into my parlor and I’ll do your hair exactly like mine! MUAHAAHA I mean how’s the weather.” (Incidentally, the annoying boy-crazy bugs are present, and decide to focus their efforts on the mice. What is it with these beetles? They’ll be extinct soon!) Out by a waterfall (a standard romantic backdrop), Tom and Thumbelina sing a song. They’re trying hard to make “cha cha cha” romantic but it’s not working. My dad watched one minute of this and declared it worse than the Ice Cream Bunny’s Thumbelina. With the song over, they’re about to kiss, when the moles (who’ve been spying on them the whole time) grab Tom and somehow tie him up in about .5 seconds. They work fast. The Mole King arrives and demands a dance with Thumbelina, prompting me to ask how well he can actually see, as he’s not crashing into everything whenever he moves. However, he does fall right back down the molehol with Thumbelina. The angry mice converge, prompting the mole minions to drop Tom and flee. Tom and the others begin to plan a rescue mission. Meanwhile, the Mole King tells Thumbelina that Tom is his prisoner and threatens to hurt him, so she agrees to th marriage. As Tom and friends approach, Thumbelina gets a scene I’ve been wondering about for a while. Namely, she asks the moles why they stay and help the Mole King. Apparently they’re scared of him and don’t have anywhere else to go. This does seem reminiscent of real-life bus, but it still seems odd to me. They get nothing out of this relationship. And so far we haven’t really seen him display any power at all. He’s just been kind of bumbling. Time for the wedding. But now Tom arrives! “Thumbelina loves me! I think.” Well, that’s stirring. Thumbelina gives the Mole King a monocle to prove that he only has two minions. Realizing that he’s been tricked, he grows furious, and a chase/fight song begins. Tom briefly wields a needle as a sword, which is a nice nod to the original character, but I have to ask: where did he get that? You don’t normally find needles just lying around. Anyway, he smashes the King’s monocle and the King is now extremely angry and starts hulk-rage-screaming and clawing his way through the dirt, but he also seems to be … quoting Shakespeare? And there are more animation errors with the mole minions. Our heroes jump off a cliff and are caught by Albertine, while the now-incoherently screaming King tunnels straight out through the side of the cliff and falls to his presumed death. The minions immediately begin fighting over his crown. Albertini hasn’t learned to land, so they keep flying back through the waterfall, through a cave, and into a strange valley. The bird casually notices a village of little people and decides to crash there. The village is pretty strange; in contrast to the modern world we’ve seen so far, it’s like a step back in time to fairy-tale era, with kings, queens, and a tiny castle in the background. And this is where the movie hits a bizarre skip and goes from quirky modern retelling, to old-fashioned cliche fairytale style. It’s hard to tell what to make of it. Thumbelina’s locket has been appearing and disappearing through this whole scene via continuity error. Spotting it, the villagers welcome her as the long-lost Princess Maia. Apparently they know long-lost royal family jewelry by sight. Her parents, the king and queen, arrive to greet her. They immediately introduce Prince Pointy Chin. “OUR LONG LOST DAUGHTER, RETURNED AT LAST! Now, marry this stranger.” The guy seems smarmy but not actually that bad. (As an interesting note: he had a cameo earlier! Watch carefully during Thumbelina’s first song.) Naturally Thumbelina’s not interested in marrying him, so her parents reveal that this prince is actually a backup (THIS POOR GUY). The lost prince she was supposed to marry was named Horace. Aaaand it’s Tom! How convenient! Okay, hold up. The parents arranged a backup betrothal because the original betrothed was missing. But Horace and Maia disappeared on the same night. What?! Their daughter was missing, so their move was to work out a backup betrothal, just in case she came back? “And so, young Chin, when you come of age, you will wed the princess, or rather you won’t because she’s missing and probably dead.” Poor Chin. But … wait. Did Horace’s parents pick out some other girl as a replacement wife for him, too? And how are there two princes in this town in addition to the royal family of Thumbelina? Maybe they’re just noblemen – but how big is this community of tiny people, that they have a royal family plus two princes? All the mice and bugs arrive. How did they get there so fast?!? They had to fly! Through a waterfall! And over a valley! I … huh? And so the movie ends with our happy couple, just married, riding in a carriage procession. Prince Chin has to ride with the annoying bugs. The End. And Tom never saw the man who raised him again.

So, a few thoughts. Tom and Thumbelina’s relationship feels shoved in. They’re the main characters so they fall in love. That’s it. Their attachment grows choppily, without much continuity, but at the same time, the moles immediately assume he’s a romantic rival. There was one thread in their relationship that seemed particularly weird to me – namely, his fear that if they actually find more people like them, she’ll find someone she likes better. The running gag of Tom’s short stature seems to play into this. Essentially, he’s got an inferiority complex. Some character development would have been nice, but we don’t get it. Instead, Prince Chin is a quick way to settle Tom’s fears and resolve the romantic plot. Even faced with a suitable, handsome (?), tall husband, the kind of guy she dreams about (as seen in her first song), Thumbelina still chooses Tom because he’s the one she’s come to truly love. Again, with more expansion it could have worked. The lack of development is partly because even though Tom’s name comes first in the title, he’s only the deuteragonist. Thumbelina is our real main character. The story starts out with her and she’s probably the best-developed character here, with the most clearly-shown arc. She’s the one with the “I Want” song and at the end, it’s her parents we meet. This is her movie. Overall, it feels like a rewritten version of the Andersen story – in contrast to Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina, which seemed more descended from Tom Thumb’s story. The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina begins with a tiny girl out of place in a big world. She makes her way into the wilderness, but still doesn’t fit in (and this turning point features a scene on the water, where she interacts with a frog/toad). She encounters bugs who mock her and call her ugly. She meets her proper mate, a tiny man/fairy prince just her size. A mole tries to force her to marry him. She saves a trapped bird who flies her to safety. Mice take her in as one of their own. At the end, she discovers a society of tiny people and her true home, becomes Princess Maia, and marries her proper mate. The events are shuffled and altered so that Thumbelina’s much more proactive and has more power. For instance, she chooses to go out into the wild, and her royal status isn’t tied to her marriage. She’s a princess in her own right. Overall, an interesting watch. It’s given me a surprising amount to think about. But I don’t know that I’d really recommend it, unless you’re bored (or doing research). I’ve found quite a few reviews for The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, but none for this little 1997 gem from Golden Films. I finally watched it, and it was surprisingly bearable. It opens with a song, led by Thumbelina flying around on a bird and making the flowers open up in the morning. Accompanied by animals and fairies, as well as a pig playing the piano (???), the song is a stirring piece that really speaks to the beauty of nature and the meaning of life. “Hi dum diddle dee, hi dum dee dum” (repeat 500x). They play the same shot of the animals jumping down a hill at least 3 times. This is not the last time they will reuse animation. That said, I immediately prefer the art style to that used in The Adventures of Tom Thumb and Thumbelina in 2002. Thumbelina is an overworked ruler trying to keep the meadow organized while animals and fairies bicker. It reminds me a little of the Tinker Bell movies. There’s supposed to be a prince, but he was kidnapped when he was a baby (or not, we’ll get to that later). Mainly this just makes me wonder about Thumbelina’s backstory. She’s not a fairy, but they never say what she is. Her duties include dealing with three young delinquents with really annoying voices, and here we have our our kid appeal/comic relief team. Actually, I kind of grinned at some of the interactions here (“What makes you think it was fairies?” Cut to signed graffiti). The work’s getting to her, so she goes to ask advice from an old and inconsistently drawn tree named Oakley. In answer to her plea for advice, he decides to tell her her own backstory. Evidently, the Fairy Queen picked two children from noble families to reign as prince and princess of the meadow. And this just raises more questions. We still don’t know what Thumbelina is. And how did she pick these babies? What were their qualifications? So his advice on government is “wait for your prince to come and then live happily ever after.” I GUESS THAT SOLVES THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION. We cut to Tom Thumb, swinging from the curtains. He’s accompanied by a dog that resembles Max from the Little Mermaid, and does not talk. (Even though every single other animal seems to talk in this world, and humans have no trouble communicating with them. Are dogs the exception? Tom then flies around on a tiny motorcycle. I am not making this up. He heads into another room, where an Arthur-esque king and several knights are sitting around a round table. Gee, I wonder if the snobby guy with the nasal voice and the ugly pet bird could be evil. Turns out it’s the king’s son Mordred I mean Medwin, who wants to expand the Castle and open an IHOG (international house of gruel) at the expense of the Great Meadow. The king, however, values nature. Tom tries to give input, but they don’t hear him. He’s eating a snack in the kitchen, when the ugly bird (a raven named Edgar who says “Nevermore” all the time and sounds like a poor man’s Iago), corners a mouse. Tom runs over to defend her with a fork and they have a discussion about how he wants to be an important knight. He feels like he’s meant for more and pulls out a plot-relevant necklace and whoa, that matches Thumbelina’s necklace! What could this mean?!? Then they both get dumped into some batter by a cooking lady with a deep gravelly man’s voice. But it’s all good. Meanwhile, Medwin meets up with some thug and plots to kidnap the king. As usual, I’m baffled by how gleeful they are at the idea of being evil. Like, you can’t have subtlety in a cartoon. And if you were wondering when this film takes place, there’s an odd reference to the War of the Roses (”just like my father to fight over a bunch of flowers”). Thumbelina’s hiding in the bushes when suddenly the King comes riding along with Tom. Tom spots Thumbelina and they talk for a minute, when suddenly the King is kidnapped just offscreen. Tom races back to the castle and is ready to ride out to the rescue, but the knights tell him to stay put. Tom gets suspicious after Medwin and the bird, in public, at the top of their lungs, talk about getting things done their way now and cackle out hysterical evil laughter. Back in the meadow, the animals come running to tell Thumbelina about construction work ruining the meadow. She flies off on her bird to talk to the king. There’s a brief mention of taking away the teen delinquent fairies’ wings if they don’t shape up, which makes me wonder if Thumbelina is a wingless fairy. But she says at some point that Tom is not a fairy, implying that this isn’t the case. More on this later. She meets Medwin, and of course trying to persuade him to save the meadow doesn’t go well. She starts to leave on her bird. Tom’s swinging on curtains again (is this how he always gets around the castle?) and they crash into each other. She assumes Tom’s part of this construction project and gets mad at him. Tom doesn’t know what she’s ranting about, but then he overhears Medwin plotting. My notes at this point read simply, “Oh no,” because, without any preamble, there’s an abrupt cut to Medwin singing and dancing with construction workers and it’s the most bizarre, anachronistic piece of dinner theatre I’ve ever seen. They’re also reusing clips again. There’s also a mention of tearing down the meadow, which is confusing because it’s kind of flat. Tom Thumb arrives with Fiona in the now-fortified meadow. At first Thumbelina and the fairies think he’s a spy, but he explains the truth and lays out a plan to sabotage Medwin’s equipment. Thumbelina and the delinquents volunteer to help, and they all fly off. We cut to a party at night in the meadow. I guess they’ll do the sabotage later? “I think somebody spiked the nectar!” someone says in the background. WHAT? Romance incoming. Tom and Thumbelina start chatting, and mention that The writing is usually okay, aside from the songs, but there are some non sequiturs and oddly emphasized lines. “This might sound kinda weird but I feel kinda like I belong here.” “This may sound even weirder but I sort of feel the same way.” “I have some strange attachment to this meadow.” “Like, you know, like YOU belong here.” A song follows, and they declare their love for one another (that was quick), and … Whaaat’s he doing with his mouth? What follows is the most awkwardly animated kissing scene I’ve ever witnessed. On another note, Thumbelina’s outfit is weird. I thought those things on her shoulders were sleeves. They’re not. They’re just … sitting there, not attached to anything. We cut to Medwin hearing about the sabotage, and this is when I realize that the party was to celebrate the successful mission and we just skipped over the entire thing. Medwin plots to “catch flies with honey;” meanwhile Tom’s preparing to go back and stop Medwin once and for all. Medwin takes a frog hostage and plots to kidnap the fairies when they come to rescue. (I don’t think that’s what catching flies with honey means.) He tosses a turtle away when it tries to stop him, and it lands right in front of Thumbelina’s throne. Hearing the news, she and the delinquents rush off to save the frog. Medwin has completely immobilized the frog by tying his tongue to a piece of grass. (Wow, really?) However, in the process of freeing the trapped animal, Thumbelina and the fairies walk right onto a piece of flypaper. (I still don’t think that’s what catching flies with honey means.) Tom rescues them from Medwin’s birdcage. Medwin was monologuing as usual and mentioned where the king is being kept, so they go to search the dungeons. When they split up, Tom and Thumbelina make up a team and immediately find the king. Medwin has an army of Saxons coming in, so our heroes recruit all the fairies and animals to fight them off. Soldiers are reduced to running and screaming in terror by tiny creatures throwing nuts and water balloons. Oh, and there’s a skunk. And an angry bear. Actually, never mind, this is surprisingly effective, even though the delinquents still aren’t funny. They don’t hit a major roadblock until they realize that they can’t lift the key to the king’s cell. Anyway, it all works out. Tom gets knighted, but now his and Thumbelina’s duties must separate them. So sad. He decides to give her his necklace of plot relevance to remember him by. This summons the Fairy Queen! And it’s revealed that Tom is the long-lost prince of the meadow oh yes of course. Why can’t he remember his childhood? The narrator says he was a baby when he was kidnapped, but he looked like a young child, probably older than five. Anyway, Tom and Thumbelina can now be married and become king and queen (”that is, as long as it’s okay with you both,” the Queen says eloquently). And to reward the delinquents, she gives them new, better wings that look exactly like the old ones. Except all yellow. For his punishment, she shrinks Medwin and Edgar down to a tiny size and puts them in the model of the castle they were planning to build. And everyone lives happily ever after. There’s a weird mention of the two kingdoms becoming one, which doesn’t make much sense, as Thumbelina didn’t exactly make a marriage alliance with the king. So, a few notes. They never say what Tom and Thumbelina are, just that they’re from royal families and they are not fairies. We never see their parents, even in the flashbacks. It’s blurry, but the only people I can identify are a squirrel and a trio who seem to be the teen delinquents, the same age. The Fairy Queen displays the ability to shrink people, and fairies are known in real-world folklore as creatures who steal human babies and replace them with changelings. So my theory is that the Queen kidnapped two children from human royal families and shrunk them. She probably had good intentions, but she’s a fairy. Their morality doesn’t necessarily match up with ours in all the stories. As for animation: there are quite a few errors and reused footage, but what stood out to me was the inconsistencies in the tiny characters’ scale. In the first picture here, Thumbelina is smaller than a man’s eye. In the second, she’s about the size of a man’s foot. Not to mention this flawless bit with Medwin walking. And no, he’s not supposed to be shrinking in this scene. That little blue figure in the background is Tom.

Our story begins once upon a time in Paris, but I’m not sure why. This tale is from Denmark but is set in France. Anyway, we take a sickening swoop through totally abandoned bad-CGI Paris under a grossly pink sky. Jaquimo the Swallow addresses the viewer and we get to my number one beef with this movie – the designs. All of the animals are very goofy and cutesified and cartoonish, while the humans are fairly realistic. Thumbelina’s animal cast does require a lot of anthropomorphizing, but I just don’t like the designs they went with. Jaquimo narrates the beginning with the old woman and the good witch, which would have been KIND OF NICE TO SEE FOR OURSELVES. We enter the story through a book, which seems a very Disney-cartoon-ish thing to do. But the live-action Tom Thumb did it too, I guess. I did not enjoy the first song, but there is one interesting moment (Thumbelina falling into a pie) that was not taken from Andersen but is clearly a nod to older Thumbling tradition. (Many of the early references to Tom Thumb specifically talk about him falling into a pudding.) The next song establishes very little, other than the fact that Thumbelina is thumb-sized. (This differs from the original tale, where she would be more accurately named Halfathumbelina.) Anyway, they tell us her size multiple times. And I don’t think anyone will forget her name. But other than that? Uh… “Thumbelina, She’s a funny little squirt/ Thumbelina, Tiny angel in a skirt/ Thumbelina, She’s mending and baking, pretending, she’s making things up” What does that TELL US? She’s unusual…okay… and she’s…imaginative? There are some little touches with the old woman that are really interesting. Like the unused baby cradle in her house, and the fact that she’s toying with her heart-shaped locket when she and Thumbelina talk about love and happily-ever-afters. Also, Thumbelina is much more high-pitched and breathy and giggly than Ariel, though you can tell it’s Jodi Benson. With the farm animals, we run once again into the animators’ design choices. That does not look like a dog. Dog legs do not work like that. Dogs are not balding unless they have a bad case of mange. Dogs do not have moustaches. And, again, I really do like how well the human characters are animated. I like Thumbelina’s long flippy ponytail, but not the weird tufts around her face. We get to Soon, which is my favorite song out of this movie, partly because Jodi Benson is a pro. Everybody talks about Let Me Be Your Wings but that one just feels trite and tired to me. Cornelius arrives on his bumblebee. That bumblebee is HUGE. Just for comparison, Thumbelina and Cornelius are maybe 2 inches high, and he looks like a horse compared to them. Also, meet the world’s only somewhat realistic-looking animal. I guess riding a talking anthropomorphic bumblebee like a motorcycle would have been too weird. Cutesy bug children pop up apropos of nothing and give them a flower chain for no reason. Are they obsessive fans of Cornelius who follow him around hoping to throw flowers? I’m not a huge fan of Cornelius’ bowl haircut. Or his outfit. Or his personality, really. He and Thumbelina are both pretty shallow. I remember my main impression of this movie as a teenager was that Cornelius was near-indistinguishable from the Toad and Mole – same motivation and everything, he was just better-looking. Of course, the Toad and Mole are clearly villains and do some awful things, but ultimately there’s not much to Cornelius rather than “wants to marry Thumbelina.” Anyway they go on a romantic flight, soaring romantically over a creek and floating romantically around a pumpkin… I mean, it’s a pumpkin. It’s an odd mix of “cutesy and campy” and “feels like they were trying to go for stirring and majestic, but didn’t quite make it.” They go home and promise to see each other again, with a vague sort-of proposal. Thumbelina gives Cornelius the necklace – of forget-me-nots. This is actually kind of brilliant. Forget-me-nots are perfectly sized for these guys, but also there’s an old superstition that a girl giving a guy forget-me-nots would be followed by bad fortune. Sure enough, Thumbelina goes to sleep in her walnut shell, but is suddenly kidnapped by a toad! And here I ask: They couldn’t have had the kidnapping scene focus on Thumbelina trying to escape, rather than a comic relief side character cartoonishly attempting to rescue her? It’s hard for me to put into words how much I dislike the toad characters. And now we get Jaquimo, and with him the film’s absolute worst plothole. Many people have commented on it. Why doesn’t he just fly Thumbelina away from the waterfall? Why doesn’t he fly her back to her house? What’s a jitterbug and why are they here? Yes, the jitterbugs. Let’s get more cutesy. “ARE YOU WEALLLLLY GONNA MARRY THE FAIWY PWINCE?!” Actually, I’m not sure what these things are, since they superficially resemble various bugs and insects – ladybugs and butterflies and things – but are, in a few cases, so cartoonish that they’re barely recognizable as insects. And then there’s the can-can-dancing birds. (Note: this song got stuck in my head for quite some time after watching this movie.) I have to question some of the set pieces here. Why is there a random book lying there in the mud? Does this area have a really bad littering problem? The Beetle arrives, being yet another more distinctly non-insectoid insect. Actually, the beetles just look like blue humans with wings. Interesting design choice with making the antennae into a moustache, but still. 0/10 on the voice talent, Berkeley. (Who allowed Gilbert Gottfried to sing? Was he really paid for this?) -2/10 on the costuming, Berkeley. You wanted her to spin around, why did you put her in that easily-dismantled outfit? Anyway, Thumbelina gets thrown out by the beetles and IMMEDIATELY DESPAIRS, but Jaquimo gives her a pep talk and they part ways, with Jaquimo planning to go to Fairyland. However, winter is coming and the search seems fruitless so far. It bears noting that autumn just started two days ago, and we’re already moving on into blizzards. Jaquimo reacts with mild surprise and dismay to the GIANT THORN STICKING COMPLETELY THROUGH HIS WING Meanwhile Cornelius gets frozen, later to be found by the Beetle and Toad. (The Toad has torn off the Beetle’s wings, which was pretty horrifying to me, but the Beetle keeps saying “Give them back.” What is he going to do with them? Can he reattach his limbs?) Alone in the snow, Thumbelina finds a conveniently abandoned shoe and sock. This place really does have a littering problem! We cut back briefly to Thumbelina’s mother, who sings her own version of “Soon.” Personally, it doesn’t feel very emotional to me. I would have focused on the voice acting in this scene, rather than the sad-looking ugly animals.